HSP HISTORY Blog |

Interesting Frederick, Maryland tidbits and musings .

|

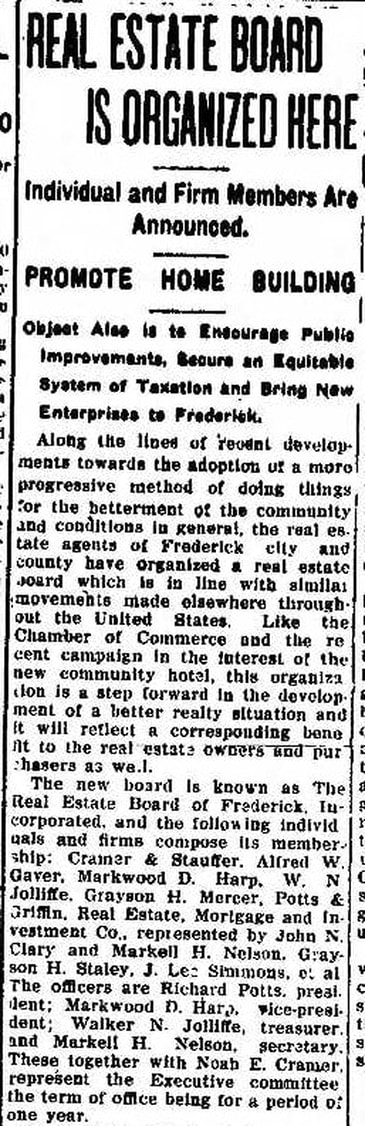

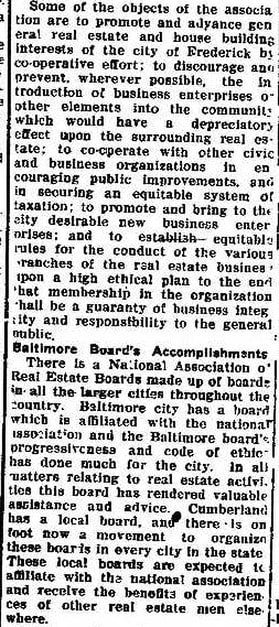

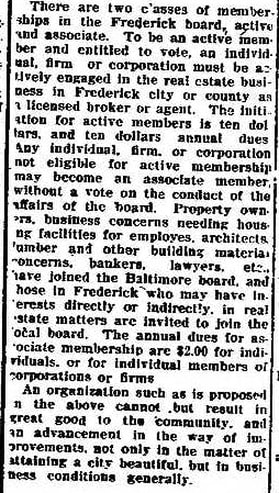

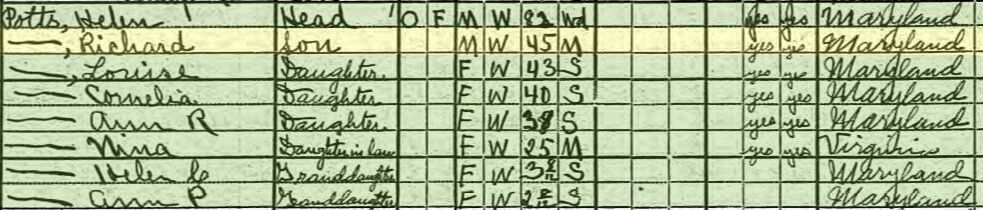

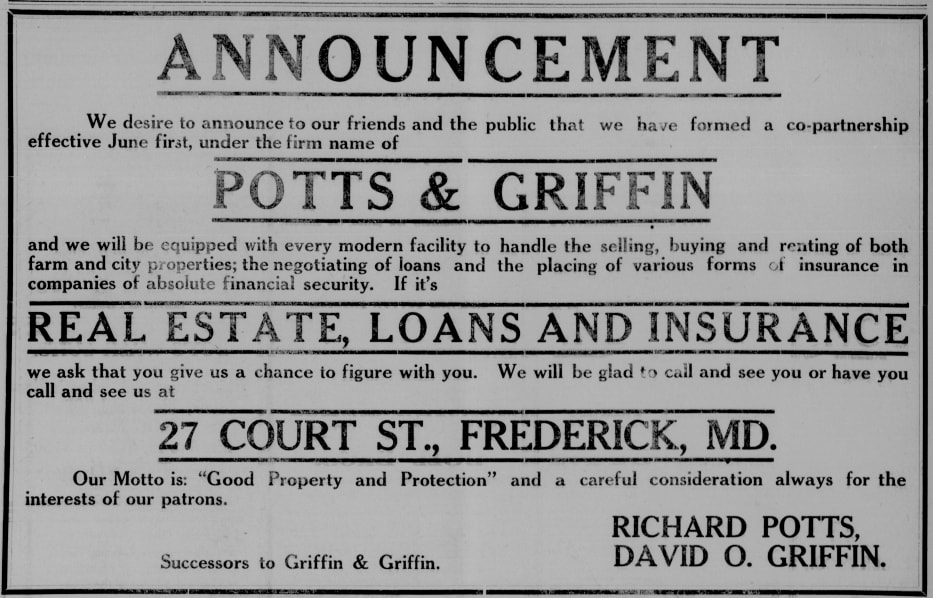

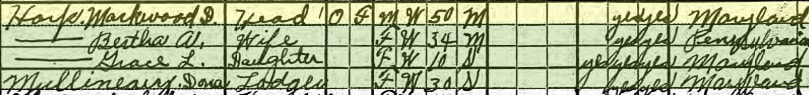

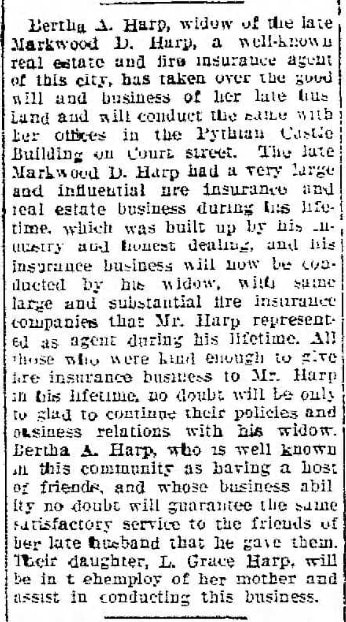

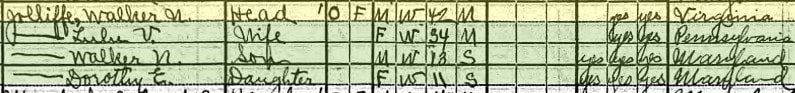

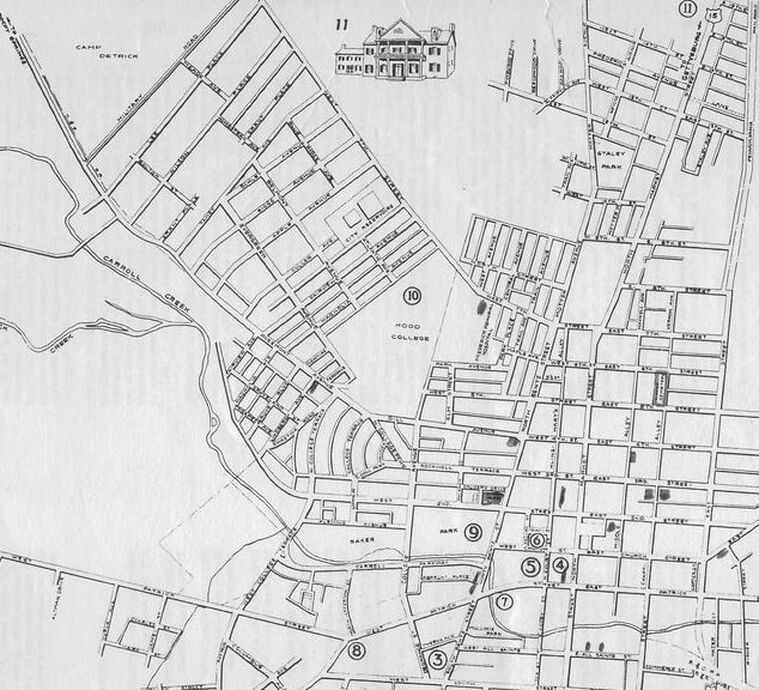

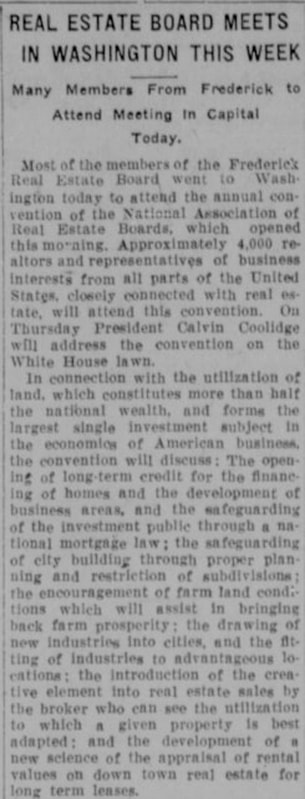

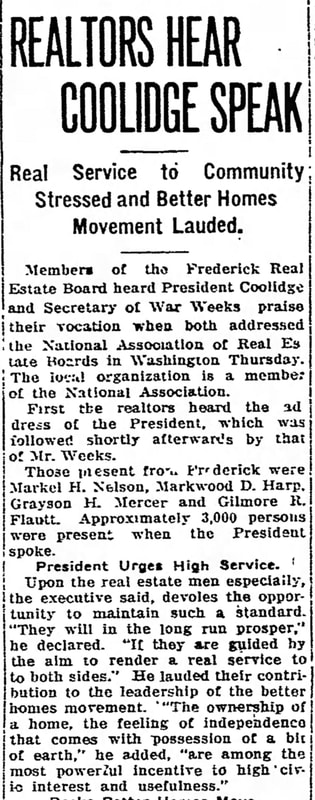

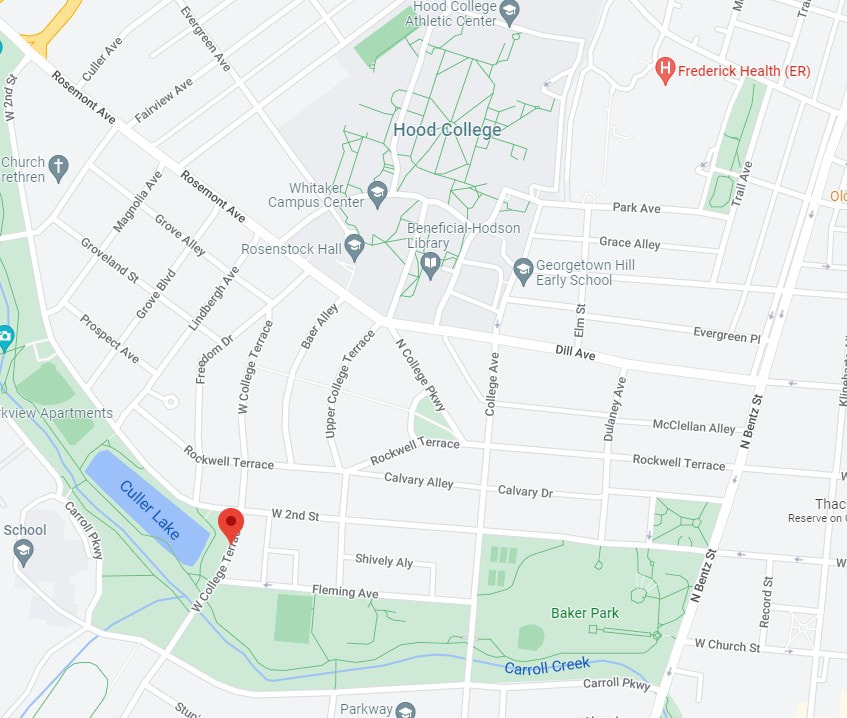

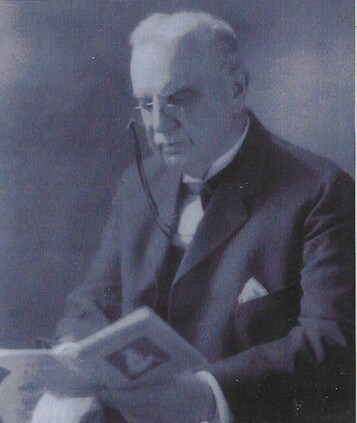

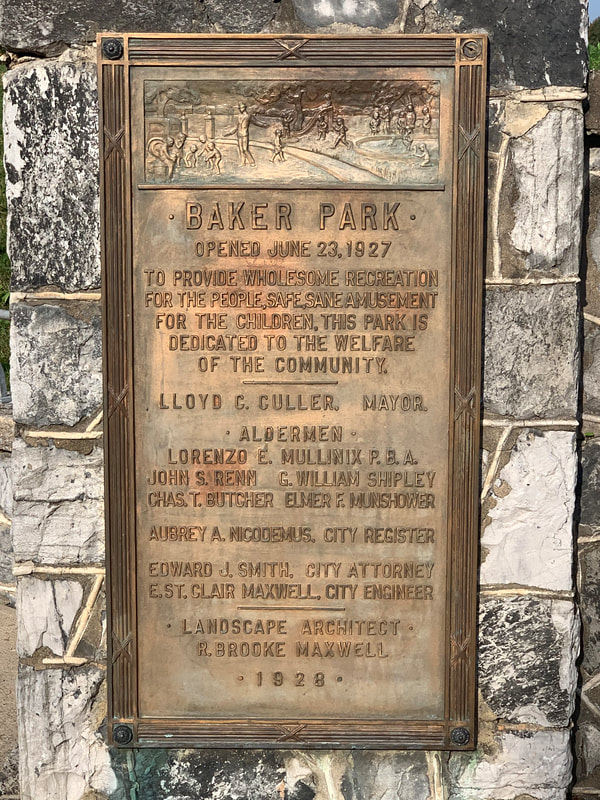

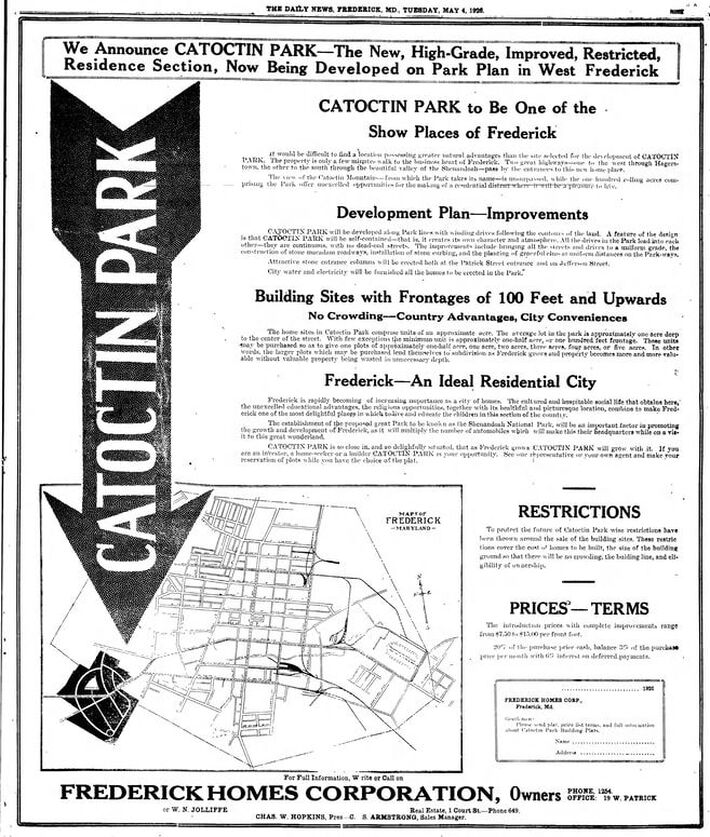

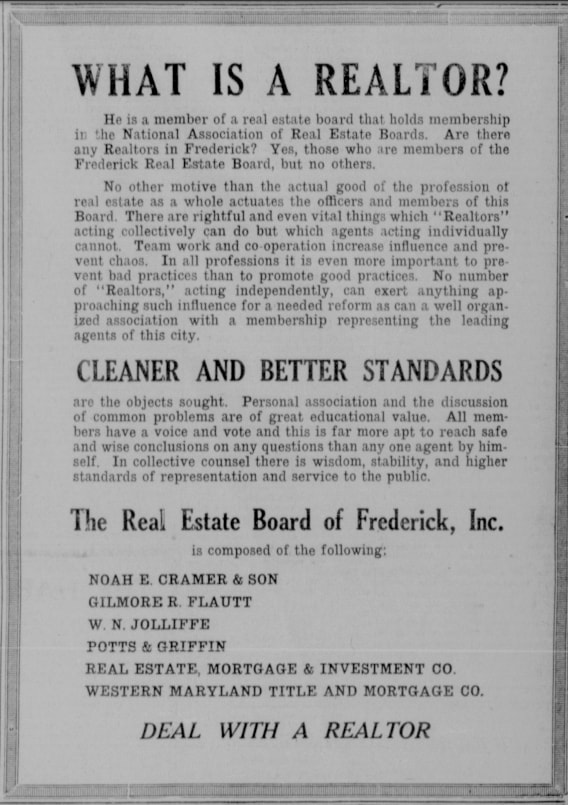

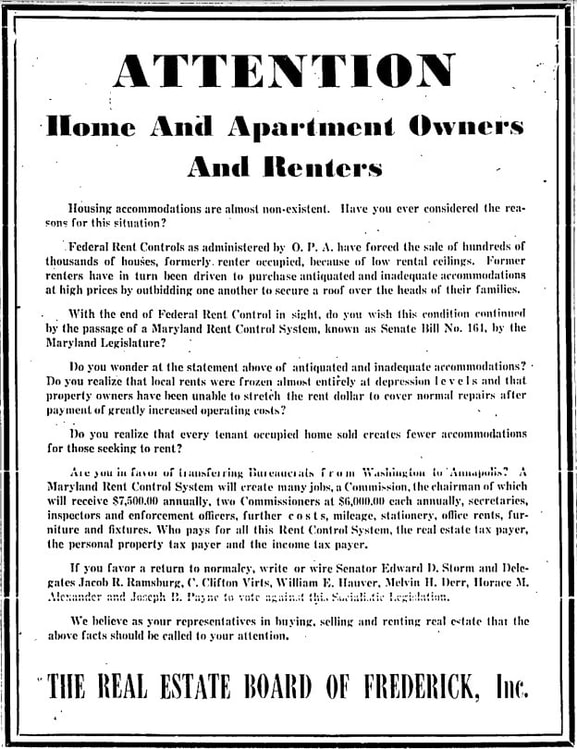

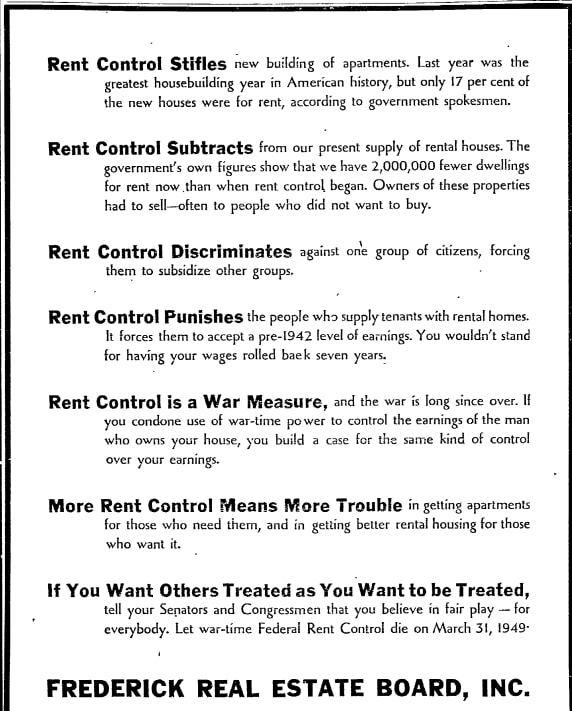

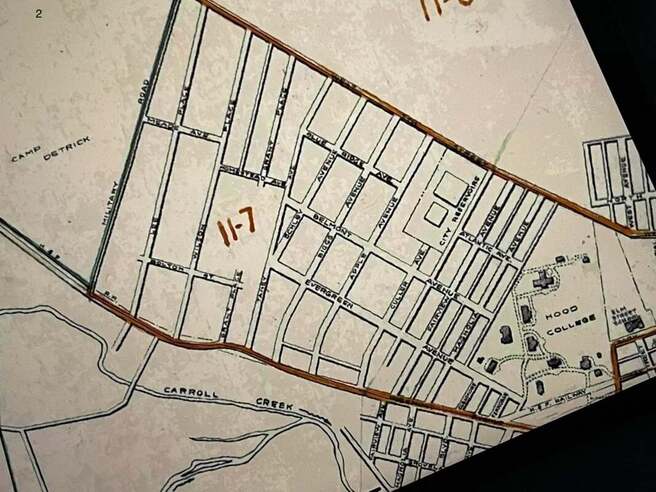

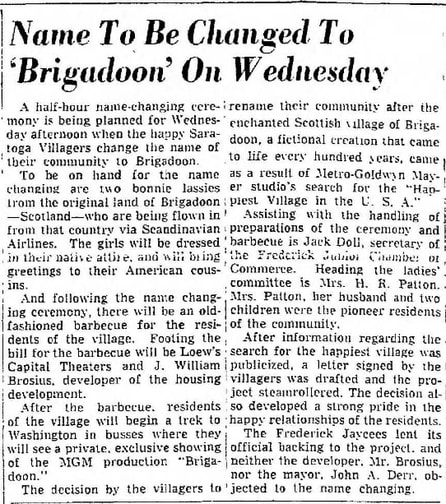

|

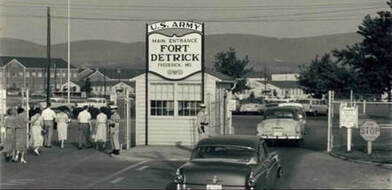

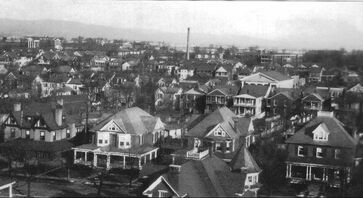

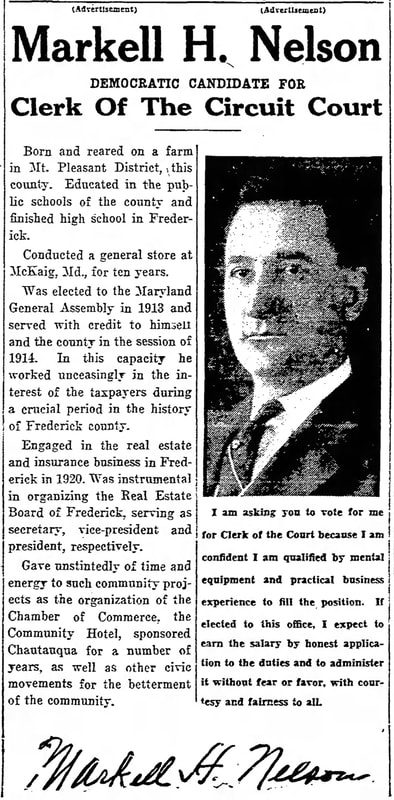

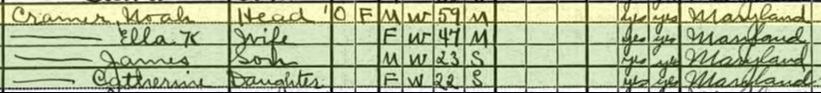

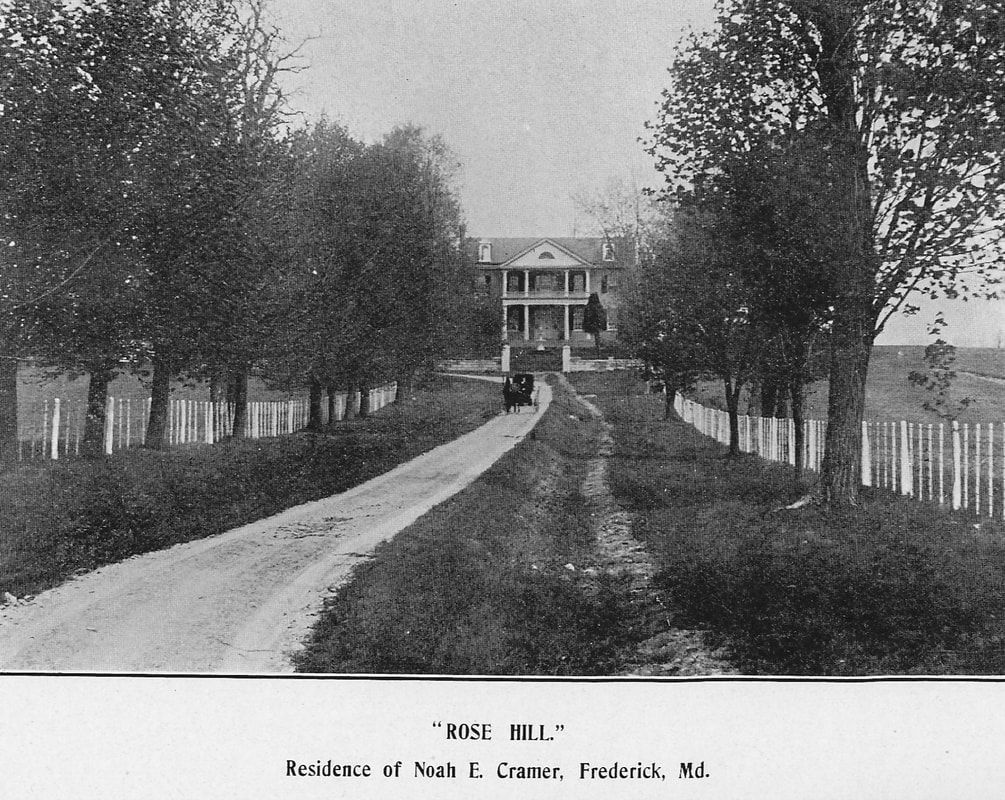

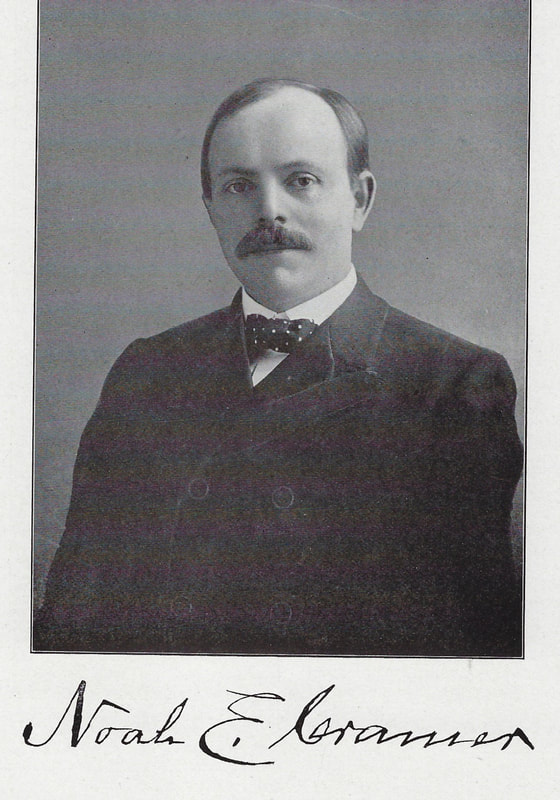

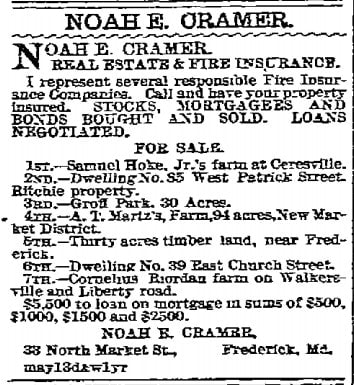

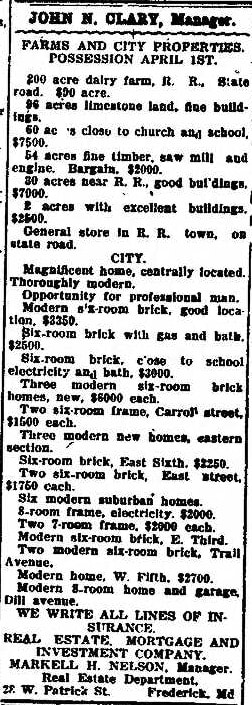

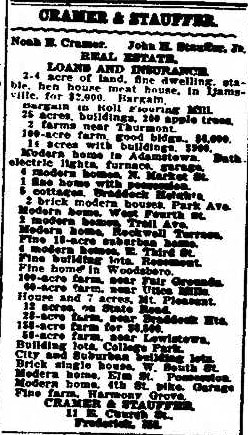

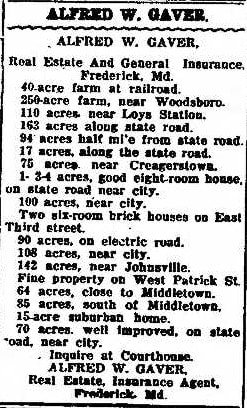

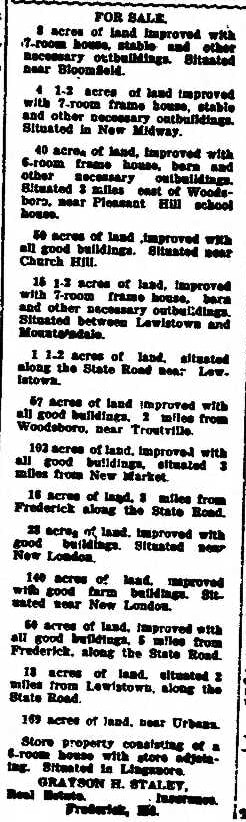

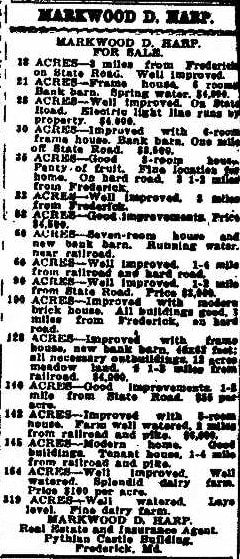

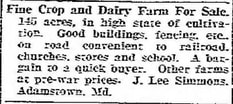

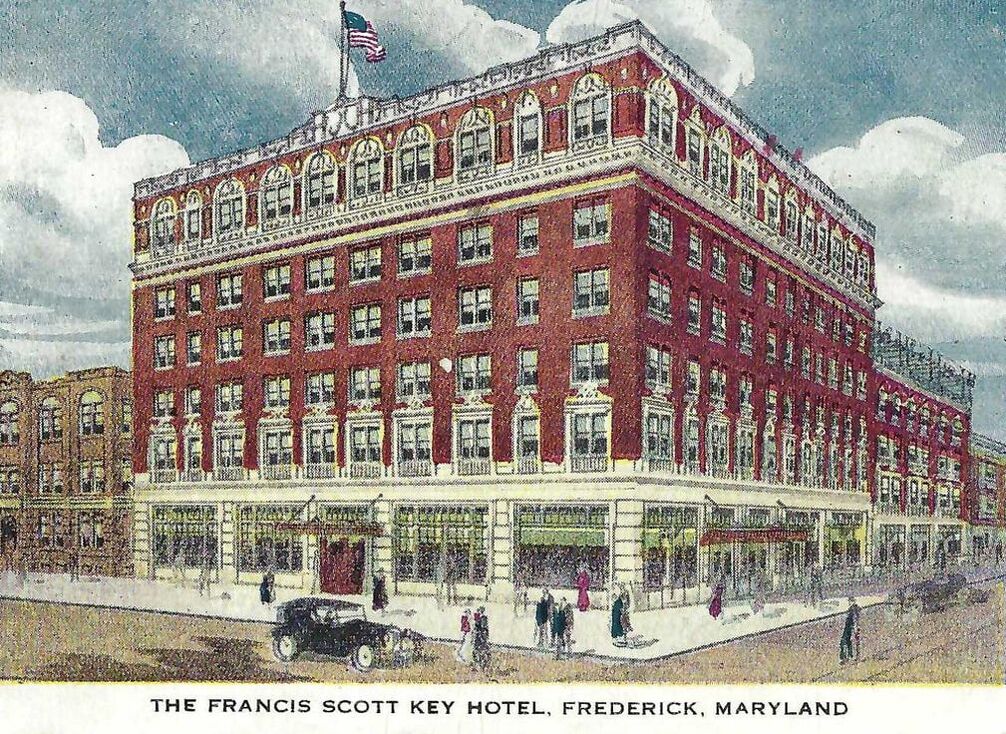

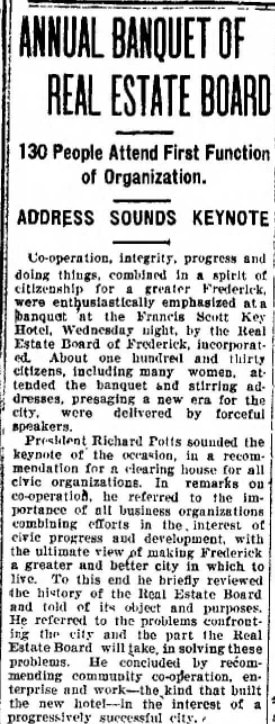

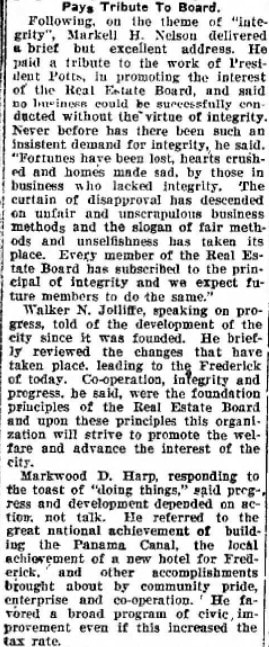

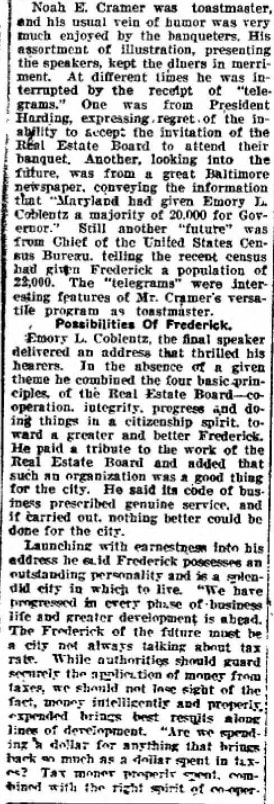

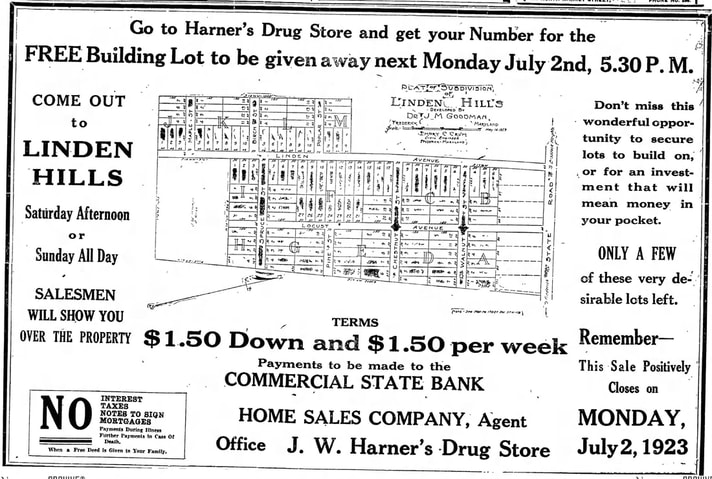

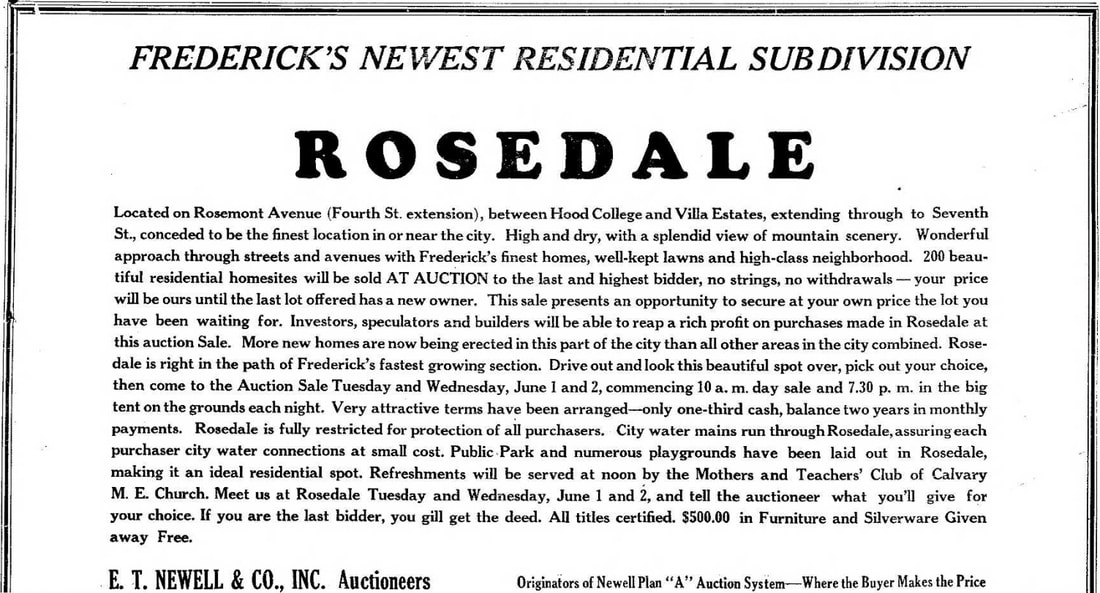

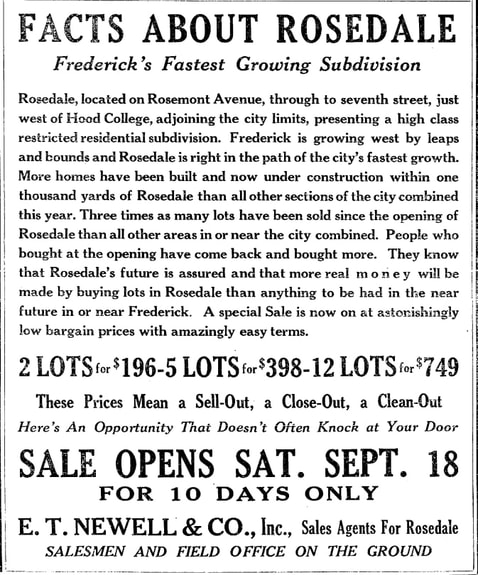

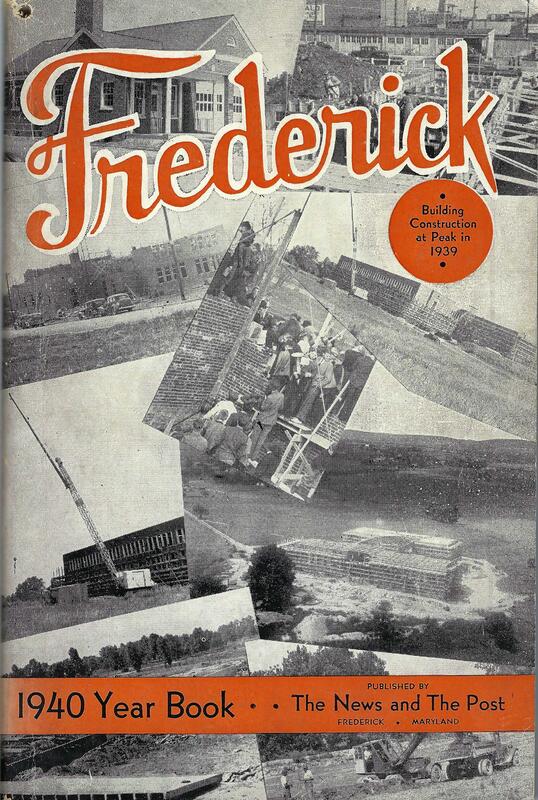

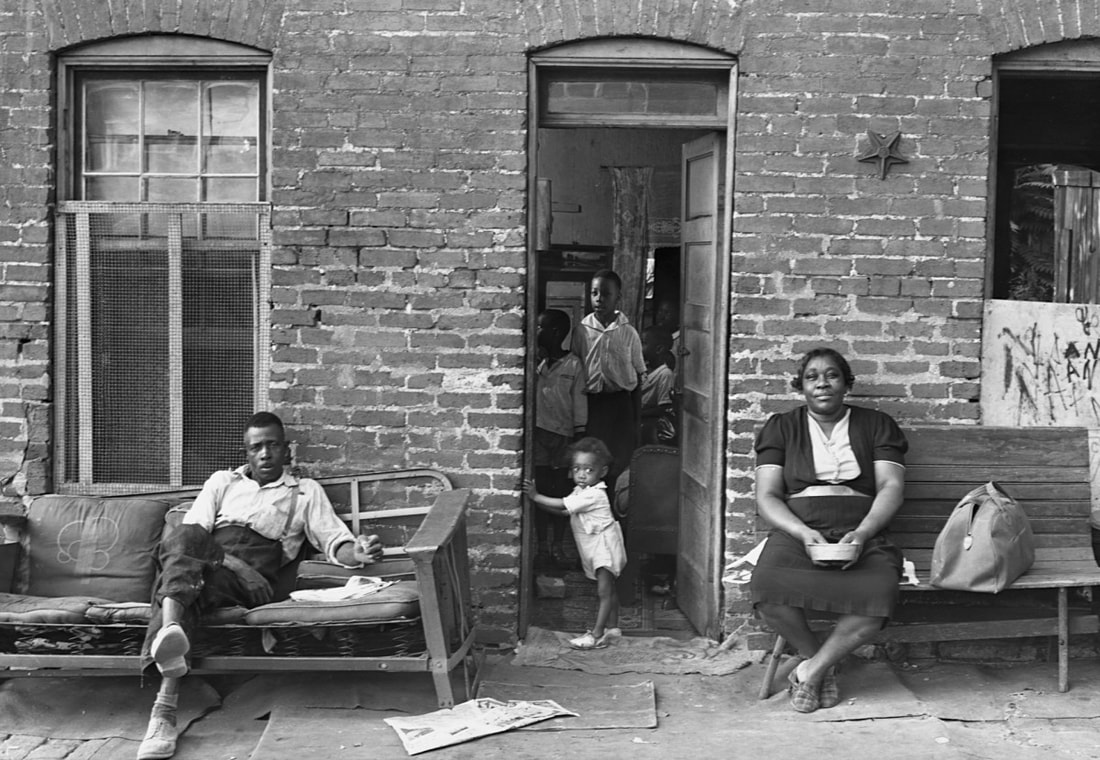

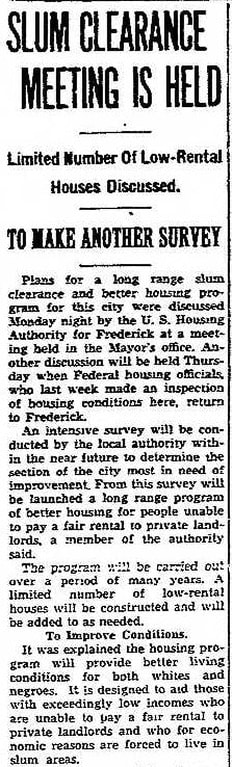

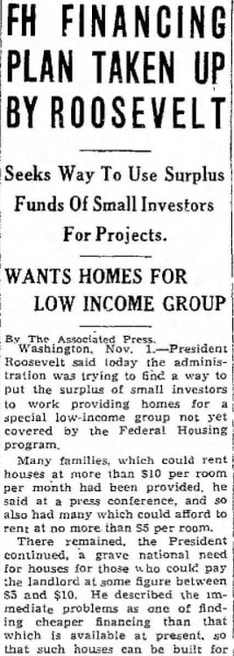

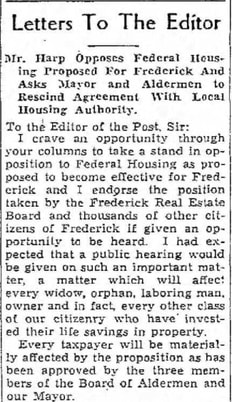

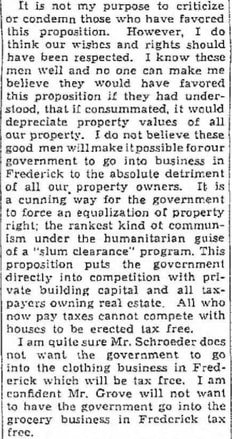

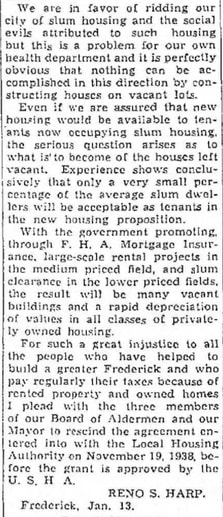

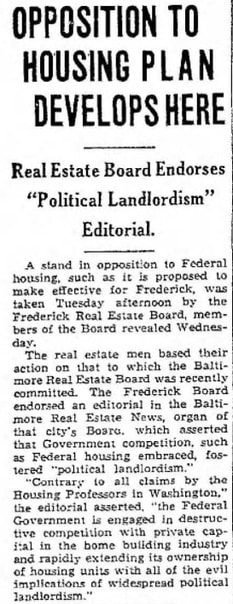

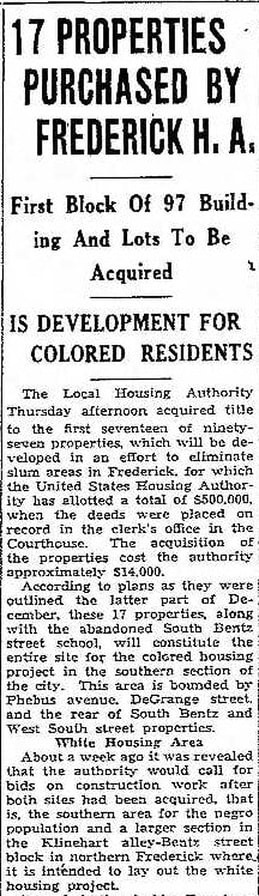

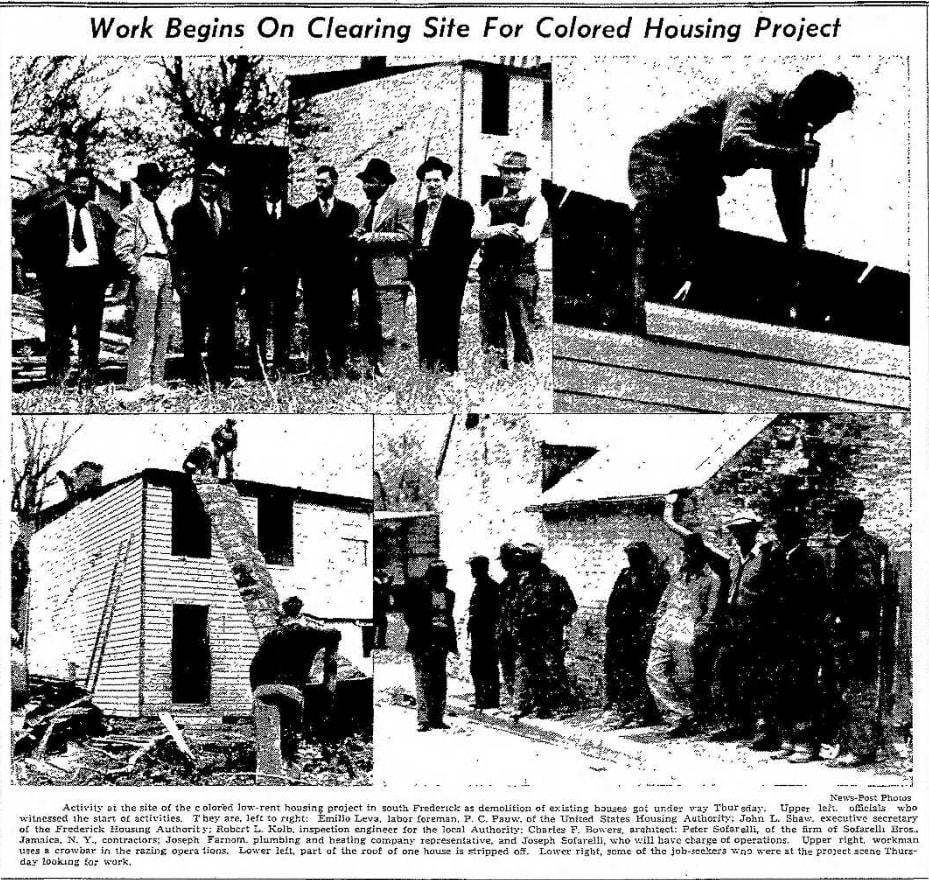

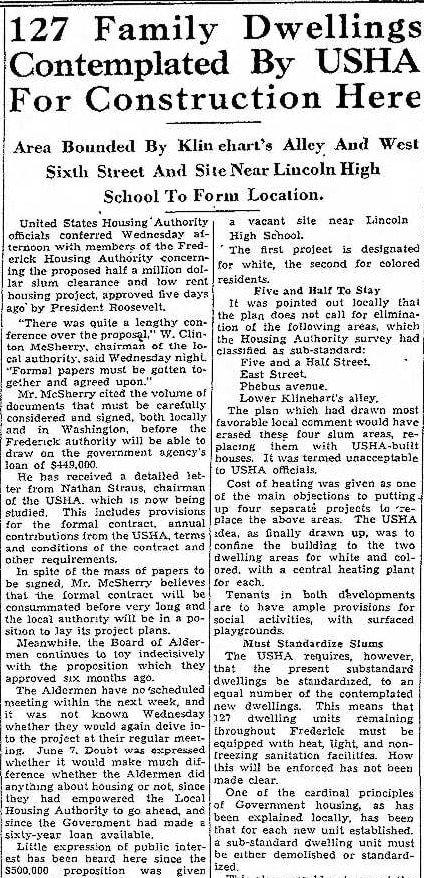

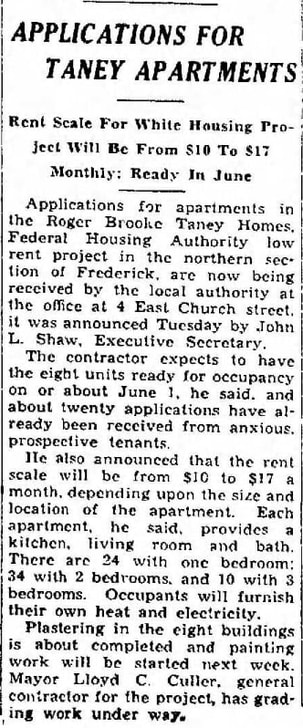

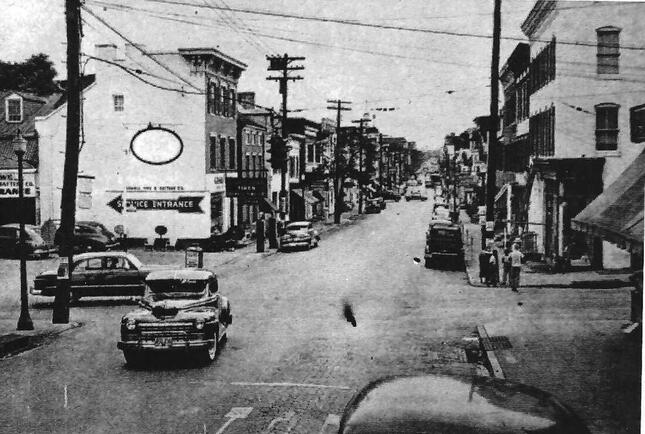

In the year 1900, Frederick City had a population of 9,296 against a county population of 51,920. To the west, Hagerstown boasted a population of 13, 591 and Cumberland had 17,128. Frederick's proverbial "die was cast" in favor of mostly agrarian pursuits in deference to industry like its major western Maryland counterparts. Selling and trading of real estate and homes had been occurring since Frederick’s rustic beginning in the 1740s. Real estate tradesmen metaphorically worked in silos. Local leading businessmen and government leaders took interest in a movement in communities throughout the country in which enclaves called “real estate boards” were being organized. The Frederick newspapers frequently ran articles announcing these entities in other states, and places within Maryland starting with Baltimore.  Birth of the Frederick County Association of REALTORS® The National Association of REALTORS® was founded as the National Association of Real Estate Exchanges on May 12th, 1908 in Chicago. With 120 founding members, 19 Boards, and one state association, the National Association of Real Estate Exchanges' objective was "to unite the real estate men of America for the purpose of effectively exerting a combined influence upon matters affecting real estate interests." The Association's founding boards included those of Baltimore; Bellingham (WA), Chicago, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Detroit, Duluth (MN), Gary (IN), Kansas City (MO), Los Angeles, Milwaukee, Minneapolis, Omaha, Philadelphia, St. Louis, St. Paul (MN), Seattle, Sioux City (IA), and Tacoma (WA) along with the California State Realty Federation.  Since 1908, the National Association has held its annual conference in numerous US cities. The Code of Ethics was adopted in 1913 with the Golden Rule as its theme. In 1916, The National Association of Real Estate Exchange's name was changed to the National Association of Real Estate Boards (NAREB). That same year, the term “REALTOR,” identifying real estate professionals who are members of the National Association and subscribers to its strict Code of Ethics, was devised by Charles N. Chadbourn, a past president of the Minneapolis Real Estate Board. Kickoff Much discussion and planning would eventually culminate in the organization of a body of this kind in Frederick, Maryland in February 1922. It would be named the Frederick Real Estate Board. The group had received considerable guidance from Baltimore City’s Board of Real Estate and another that had been recently started in Cumberland. The first official announcement would take place at a meeting held on February 9th. On February 9th, the Frederick News shared information about this new group's start and exclaimed: “Along the lines of recent developments towards the adoption of a more progressive method of doing things for the betterment of the community and conditions in general, the real estate agents of Frederick city and county have organized a real estate board which is in line with similar movements made elsewhere throughout the United States. Like the Chamber of Commerce and the recent campaign in the interest of the new community hotel, this organization is a step forward in the development of a better realty situation and it will reflect a corresponding benefit to the real estate owners and purchasers as well.” The early goals of this organization included “the promotion and advancement of general real estate and house building interests of the city by cooperative effort; and, where possible, the discouragement and prevention of the introduction of other elements into the community which would have a depreciatory effect upon the surrounding real estate.”  Tanneries were among those businesses considered "dirty industries." Tanneries were among those businesses considered "dirty industries." Frederick’s Real Estate Board took aim at cooperating with the Frederick Chamber of Commerce and other civic and business organizations in encouraging public improvements to accommodate property owners and securing an equitable system of taxation. The new group set out to further promote Frederick as a location for new and desirable business enterprises, while making important strides to rid, or clean-up, existing “dirty industries” for the betterment of the community. Lastly, this body hoped to form equitable rules for the conduct of the various branches of the real estate business upon a high ethical plane. They sought to establish the fact that membership in the organization would be a guarantee of business integrity and responsibility to the general public. The Frederick Real Estate Board would eventually expand to cover the entire county. In addition, important affiliations would be made between this local Board and both The Maryland Real Estate Board (founded in 1906) and the National Association of Real Estate Boards (founded in Chicago in 1908). In doing this, Frederick’s members received the benefits of experience, advice and best practices from a network of real estate professionals elsewhere in the state, and country. Today, the Frederick Board of Real Estate Board is known as the Frederick County Association of Realtors.® In the beginning, the initiation cost to become a member was $10, with an additional dues cost of $10/year. The local newspaper of February 9th concluded by saying: “An organization such as this cannot but result in great good to the community, and an advancement in the way of improvements, not only in the matter of attaining a city beautiful, but in business conditions generally.” The Inaugural Board The driving forces behind Frederick’s inaugural Real Estate Board were a talented group of experienced Frederick professionals. These 12 gentlemen would meet once a month in one another’s offices on a rotating basis. The first officers included Richard Potts (President), Markwood D. Harp (Vice President), Walker N. Joliffe (Treasurer), Markell H. Nelson (Secretary) and Noah E. Cramer. The latter, Mr. Cramer (1860-1930), had been Frederick’s leading realty professional and a well-respected businessman over the previous few decades. Noah E. Cramer was in great company with the initial Board of Directors for the Frederick Real Estate organization. Six years earlier, President Richard Potts (1873-1945) was in the center of the College Park situation, as a liaison of sorts between the West Virginia-based Swastika Realty firm who owned the building lots, the city officials of Frederick, and customers interested in buying into this subdivision. Potts recognized the importance of local knowledge, insight and connectivity. This prompted him to act in advocating for Frederick to have its own Board of Real Estate in the first place. Richard Potts Richard Potts (1873-1945) came from a prominent family who lived in Court House Square. He was the 4th generation to live at the prestigious home located at 100 North Court Street, on the corner of West Church Street, and across from Frederick’s Courthouse Square. His great-grandfather was Richard Potts, a noted politician and leader in Frederick throughout his lifetime. After receiving an early education at the Frederick Academy, followed by the Episcopal Academy in Alexandria, VA, Mr. Potts went to work as a clerk at the Central National Bank and Trust Company. In 1914, he entered the real estate business, forming a partnership with insurance salesman David O. Griffin. The firm of Potts & Griffin would last for 30 years until 1943, and was headquartered with an office at 27 N. Court Street, just a short distance from Mr. Pott’s home. Markwood Doub Harp (1869-1926) was a Frederick County native from Myersville who received his education in the local schools there. He came to Frederick City for professional work and served as Frederick County’s Deputy Register of Wills before becoming Clerk to the County Commissioners. He would leave that position to become a realtor and lived at 313 Dill Avenue (renumbered to 269 Dill Ave today). Mr. Harp’s brother, Reno S. Harp, was a leading attorney in town. In the Real Estate Board’s second year, Markwood Harp would take the reins as president. Sadly, Mr. Harp would die just a few years later in late 1926 after a three-week illness attributed to heart trouble. He was 57 years old. Harp's widow, Bertha Almeta (Kiracofe), would assume his position in selling real estate and insurance after his death. She would work out of her husband's office at the Pythian Castle on Court Street, and was assisted by her daughter. This would make Bertha, Frederick's "first-known female real estate and insurance agent." She lived from 1885-1965. Walker Neill Joliffe was born at Clearbrook near Winchester, Virginia in 1876. He grew up on the family farm to Quaker parents. He clerked at two different stores in his native Frederick County, (VA) before coming to Brunswick in 1896 to clerk for the general store of Jones & Robinson. In 1900, Mr. Jolliffe entered a partnership with H. M. Jones, of Brunswick, and in 1904 these gentlemen established a dry goods, clothing, boot, and shoe store in Frederick City. Immediate success prompted the pair to open a store in Mr. Jolliffe’s native home city of Winchester. He would soon take up residence at 307 Rockwell Terrace. Walker Jolliffe transitioned over to working here in Frederick in the real estate business in 1919 with his brother, John. The two ran an office at 122 North Court Street. Walker Jolliffe would experience success in his newfound field but would die in November, 1931 of tuberculosis shortly after being sent for treatment at the noted asylum in Sabillasville (MD). He would be fondly remembered at the Board of Real Estate’s 10-year anniversary gala in 1932. Markell Henry Nelson (1882-1973) was born on a farm in Mount Pleasant District in 1882. He acquired his education at the Central School and later went on to the Frederick Academy. For years Mr. Nelson clerked in a store at Sandy Spring, across the Potomac River from Harpers Ferry. Later, he became engaged for a time in the insurance business in Baltimore. In 1908, Markell Nelson bought a mercantile business at McKaig, a small crossroads east of Frederick at the intersection of Gas House Pike and McKaig Road. Mr. Nelson won election in 1913 to serve in the House of Delegates of the Maryland General Assembly, beginning in 1914. In 1922, he was working as manager of the real estate department for the real estate, mortgage and investment company of John N. Clary with an office at 28 West Patrick Street. In a few years, Nelson would launch his own real estate firm with a business office located at 31 North Court Street. Earlier in his working career, Noah Edwin Cramer (1860-1930) entered the business world in the dry-goods store of his brother, George L. Cramer. Here, he was employed as a clerk, and he remained with his brother for some time. While still a young man, he re-located to Frederick City, and established himself in the real estate and loan business. From the start, he met with much success, becoming one of the best known and most prominent businessmen of the city by the first decade of the 20th century. Cramer also possessed the general confidence of business and financial circles both here and statewide. Besides his real estate and loan business, Mr. Cramer was interested in various enterprises of the county. He also had a pretty interesting home for himself and family—the former home of Maryland governor, Continental Congress member and Revolutionary War veteran Thomas Johnson, Jr. He would also live at 117 Record Street. In 1922, Noah Cramer helped champion the Frederick Real Estate Board, while a partner in the firm of Cramer and Stauffer. Other founding members of Frederick's real Estate Board in 1922 included John N. Clary (1867-1949), Alfred Wesley Gaver (1876-1940), David Otho Griffin (1884-1954), Grayson Henry Mercer (1879-1945), James Lee Simmons (of Adamstown) (1860-1961), Grayson Hedges Staley (1881-1965) and John Hanson Stauffer, Jr. (1894-1958). On February 9th, the day after the founding organization was announced, the following listings could be found in the Frederick News-Post representing the business interests of all the Board members. The Work Begins One of the Board of Real Estate’s first projects involved advocating to have Court Street widened to aid the major hotel project currently under construction. The widening became a reality thanks to the proactive efforts of the new Frederick Real Estate Board. Ironically, some of the founders would maintain offices on Court Street as well, so in retrospect, it can be considered a “double-win.” In the immediate years to come, other streets such as Bentz, Patrick and West 2nd would also be championed by the Real Estate Board to also be expanded in width. In September of 1922, plans were reported for a new housing development to be built on Frederick’s north end between Motter Avenue and North Market Street. This was the former farm owned by the Neidig family consisting of 20 acres. This would be the first major development under the purview of the newly formed Frederick Real Estate Board. A personal connection came with vice president Markwood Harp making the purchase from William C. Neidig in collaboration with his brother, attorney Reno Harp, and Ernest D. Michael. This neighborhood would become Frederick’s new north end, and soon took the name Maple Park. The Francis Scott Key Hotel cost more than a million dollars to build, but the five-floor, 220-room hotel opened to tremendous fanfare on January 8th, 1923. It would serve the influx of traveling salesmen and other business and government employees passing through. It gave birth to local tourism and visitors, while becoming the center of Frederick’s social scene for decades to come. With a year under their belts, President Richard Potts and the other officers of the Frederick Real Estate Board brought together the larger membership for their first annual meeting in January of 1923. The location was fitting, as this represented one of the first gala events in the rich history of the Francis Scott Key Hotel. In the week following the banquet, the Frederick News featured an article calling for grooved rails to replace existing trolley track on the city’s major thoroughfare of Market Street. This was more of a safety provision, as the subject had been raised earlier by the local Chamber of Commerce. Meanwhile, lot sales for another new development would soon become available for Linden Hills, a subdivision located west of Frederick City along today’s West Patrick St/US40, commonly referred to as the Hagerstown Pike at the time. This area was developed by Dr. J. M. Goodman, a leading physician of town, who originally hailed from Monroe County, West Virginia, but married Estelle Hoke, daughter of Samuel Hoke. The Hokes owned property west of Frederick to the south of the National Pike (just west of today's Route 15) which became the site of the Linden Hills subdivision. Lot purchases would be handled by the Home Sales Company of Wyckoff, New Jersey. In the last two weeks of June, 105 lots here in Linden Hills would be sold. Another early achievement of the Board, in addition to receiving its national charter from the National Board of Real Estate, was to make meaningful connections to like real estate boards around the state, and particularly on the national level. Gaining knowledge, know-how and best practices from others would certainly benefit Frederick, both the city and county. Many Frederick Real Estate Board members would attend the national conference in Washington, DC in December of that year. The Board of Real Estate’s executive committee also set its sights on legislative issues. In fall of 1923, the Board vocalized their desire to have mortgage rates repealed, following the lead of all other counties in Maryland. This would continue to play out as the Board would lobby political leaders and candidates for election on the local, state and national levels. The Frederick Real Estate Board put collective energies toward bringing town-friendly business enterprises here to further enhance quality of life for residents, while opening new opportunities for employment. One such example was a new heating plant working under the name of the Hunter Heating Company. Current Board of Real Estate president Markwood D. Harp would serve as Hunter’s first board of directors’ president. Returning to the central mission of real estate in respect to community building, the College Park addition to Frederick City was still expanding in the form of West College Terrace, south of Rosemont Ave. North of this thoroughfare was the Rosedale subdivision with houses popping up on the three principal avenues: Magnolia, Fairview and Culler. The Frederick Real Estate Board had a better handle over sales and the needs and wishes of locals as opposed to out-of-towers like Edward L. Williams who introduced the original College Park development plan. A second, well-attended banquet of the Frederick Real Estate Board would be held in February 1924 at the FSK Hotel, with a comforting message of a likely boost to the real estate trade in Frederick thanks in part to major roadway improvements planned for the immediate future. This would come to fruition in 1925 when highways were completed to the major cities of Washington, DC and Baltimore. Although not the interstate highways we know today, these corridors made the large, metropolitan areas considerably easier, faster and safer to reach by automobile. And speaking of the nation’s capital, many members of the Real Estate Board of Frederick would be in attendance for The National Association of Real Estate Boards conference held in June 1924. Here they met professionals from around the country, gained valuable ideas and were addressed by the sitting president of the United States, Calvin Coolidge. Members of Frederick’s Real Estate Board came back home re-energized and poised to commence higher-end marketing to the masses. This was done by the organization and individual members themselves. The West College Terrace project was the first real test of the Board of Real Estate’s marketing prowess, and the end-product certainly “lived up to the hype” as this neighborhood continues to hold the greatest value within Frederick City limits still today as does Rockwell Terrace. Financing the Purchase The home ownership message was sent loud and clear. However, the most important point of all was delivered—deal only with a bonafide realtor for best results and satisfaction. Next, the Board set in on another one of its initial goals, that of making it possible for more individuals to be able to purchase their own homes. This hinged on one major factor—the money to do so in the form of financing a sale. Buyers and investors pay so much attention to where a property is located, what features it offers, and how much it costs. However, every real estate sale ultimately depends on the buyer’s access to funds. During the 1700s and 1800s, most residents had no way to own a home or specialized retail location. Few possessed the large sums of money to buy property outright, and banks surely wouldn’t lend money to average, working class people. Mortgages would not become commonplace until the US banking system was stabilized in the 1860s. After a few decades of experimentation by the banks, mortgages became popular across the country in the 1890s. Mortgages in the early 1900s typically consisted of a term of five years and required a down payment of 50%. These were structured with interest-only payments and a balloon payment for the entire principal at the end of the term. Buyers could renegotiate loans every year if they pleased. From the beginning, the Frederick Real Estate Board organization began encouraging strong partnerships between local real estate professionals and the early lending institutions of town, both working in unison to secure necessary mortgages and funding on behalf of clients wanting to buy property for land or business use. Through much of this time, two leading figures in the home and community growth game in Frederick were banker/town philanthropist Joseph D. Baker, and Frederick construction contractor/mayor Lloyd C. Culler. Mr. Baker, the director of the Citizen’s National Bank, made the loans to new home buyers, while Mr. Culler had his hands full with building houses. Both gentlemen would help grow the real estate trade here in Frederick. Successful as a businessman, Lloyd C. Culler decided to see how he would fare in the political realm. He was elected as a Frederick alderman in 1913 and served as president of this group for the next three years. In June 1922, Mr. Culler was elected mayor, an office he held for 22 years as residents re-elected him seven times. During that time, he helped guide the city toward improving its recreational, water and sewer facilities along with upgrading streets and other buildings. Joseph D. Baker’s legacy is that of Baker Park, which not only gave residents a recreational haven, but also helped sell homes. The oldest portion of today’s park, near North Bentz Street, had previously been used for industry. It had been the site of the Old Town Mill, built by Jacob Bentz in the late 1700s. The mill, with its mile-long race, was still intact during the first quarter of the 20th century, a time when the city started to expand outward. Another business endeavor, the Mountain City Creamery was located immediately to the north of the Bentz Mill, but this building was demolished around 1910 to make way for the Frederick City Armory, which still stands today as the William Talley Recreation Center. The Frederick City government began acquiring land for the creation of a large municipal park along Carroll Creek, spurred by the advent of the upscale College Park development on the city’s northwest side. It would be necessary to do something about the visual and olfactory situation of a few existing farms sitting in the confines of Carroll Creek’s flood zone. In 1926, the initiative still lacked two necessary properties, and it was Joseph Dill Baker and his wife who stepped in and purchased this land and donated it to the city. After this acquisition, the City hired Baltimore landscape architect R. Brooke Maxwell to prepare a design plan, and work quickly began to create parkland that extended from Bentz Street to West College Terrace. In 1927, this park was dedicated to Mr. Baker by the mayor and board of aldermen in recognition of his years of service to the city. Because of all he gave to the town, Joseph Dill Baker was dubbed “Frederick’s First Citizen.” The new park became a key amenity, and selling point, for homebuyers in the greater College Park area of town. The Crash More affordable houses would be built in another subdivision begun on the southside of Carroll Creek. This was on the west edge of town past Upper College Terrace and the new Baker Park. This would take the name of Catoctin Park with construction starting in 1926. A definite shift now saw people regularly moving out of the historic downtown area to the myriad of suburban neighborhoods to the west. As the “Me Decade” (as it was called) of the 1920s was slowly coming to a close, 1928 brought the election of Richard Potts as the local Board of Real Estate president. The year also included the widening of Urbana Pike, the main road between Frederick and Washington, DC. Eyeing the opportunity to be a bedroom community, the Board started advertising in earnest the pride and many benefits of being a homeowner in Frederick. Since the end of the World War, the "Roaring Twenties” had been a time of wealth and excess. Building on post-war optimism, rural Americans migrated to the cities in vast numbers throughout the decade with the hopes of finding a more prosperous life in the ever-growing expansion of America's industrial sector. Frederick saw much residential and civic growth as a town during this time, but not a great deal in respect to industrial growth. The decade closed with the Wall Street Stock Market Crash in the autumn of 1929. It started in September and ended late in October, when share prices on the New York Stock Exchange collapsed. This would usher in the time period known as “The Great Depression.” The 1930 US Census showed Frederick City’s population at 14,434 and counted roughly 3,200 single family homes in town. The county’s population at the time was 53,861 with a total of 11,545 dwellings. Frederick City’s growth in residents over the preceding decade was up 28%. Over the next 10 years, the county seat’s population would only grow by 10%, primarily as a result of the severe worldwide economic downturn. Life in Frederick during the Depression era was not as severe as other parts of the country, including cities and rural areas. Since Frederick was built primarily on agricultural industries instead of mechanized/labor heavy industry, it fared rather well, but did not attract an influx of newcomers in search of jobs for economic recovery. The existing community grew, and amazingly, building continued as people realized Frederick was still a very special place to live. Richard Potts would serve as president of the Frederick Real Estate Board again in the year 1935. This same year, the organization entered an interesting partnership with the Frederick County Farm Bureau and the Pamona Grange. The purpose was to create a report on behalf of the “Economy and Efficiency Committee” that would study the county’s affairs. Most of the county officials were called in consultation, and various phases of the county’s activities were studied for the purpose of outlining possible changes and economies. In February, the report was presented at the courthouse for the benefit of the citizenry along with the Frederick County delegation to the Maryland General Assembly. The report recommended several economic plans and several sources of increased income for the county to relieve the tax burden upon real estate.  1929 aerial photo of northwest Frederick City showing Rosemont Ave (left) and W 7th St (right). The area between both these principal streets would see continued growth in the 1930s in the form of Rosemont, Villa Estates and Rosedale. If you look closely you can see Hood College's Alumnae Hall and smokestack towards lower left.Further northwest, (above smokestack) note the small huts that constitute Camp Detrick and its adjacent airfield. Suburbanization Continues The Rosedale subdivision had originally been proposed with property bought in 1931 from Henry Krantz, son of Edward Krantz who owned this property earlier. This land represented the area immediately north of the Brunner-built Schifferstadt farm, the oldest surviving home in Frederick City. This parcel stretched between 7th Street (known earlier as Montonqua or Yellow Springs Avenue) and Rosemont Avenue. It encompassed the area east of Wilson Avenue in Villa Estates to Fairview Avenue of the Rosemont Addition. At the time, Rosedale’s purchaser was a farmer named Jacob A. Kidwiler who lived on the land where Frederick High School is today located. He would sell this parcel to the Board of Education in 1938 for that very purpose. His wife is said to have suggested the name Rosedale as a tribute to her mother. Planned streets would take the name of modern men who served as pillars in the community and included Hood College president Joseph Henry Apple, John M. Culler and Elbridge F. Biggs. John M. Culler was a grocery store owner who lived on Elm Street. Sadly, he would die in a car accident in December, 1935 on MD 26 near Mount Pleasant while returning home from taking his son back to school at Western Maryland College. Biggs Avenue was named for another major Rosemont development investor, John M. Culler’s brother-in-law, Elbridge F. Biggs, Jr. Mr. Biggs was a telephone industry pioneer and bought some of the first lots on Fairview Avenue, where he made his home. The streets were named in honor of the former businessmen on a 1937 plat for the Kidwiler’s Rosedale subdivision venture. This development continued the cultural geography trend which usually pinpoints the northwest parts of towns as being the most attractive for suburban residential neighborhoods. This was primarily due to prevailing winds carrying industrial pollution in an eastwardly direction. An adjacent pond to Kidwiler’s original farm property was formed to better manage stormwater overflow from neighboring Carroll Creek. This pond of water became creatively labeled as a lake. It was originally called Kidwiler Lake, but in 1940 this man-made body of water was renamed Culler Lake in honor of Mayor Lloyd Culler. The Kidwilers did get a park named for them near the convergence of the Villa Estates subdivision and Rosedale. Kidwiler Park can be found on the west side of Schley Avenue and serves as a nice amenity for these neighborhoods up through the present. From 1937-1940, more lots were sold and built upon in the various subdivisions located northwest of town. Residential streets, we know today, began to take shape here as Frederick building construction was at an all-time peak in 1939. Ten years after the 1929 Stock Market crash, Frederick was growing by leaps and bounds, as was attested by the front and back cover of the Frederick 1940 Year Book published by the Frederick News-Post. In that same year of 1940, the Frederick Board of Real Estate had dwindled to only five members. The organization was delinquent in paying dues to the National Association of Real Estate Boards and was dropped from membership in May. Thankfully, the Frederick Real Estate Board would address this issue diligently and gained reinstatement in November. A new Charter document would be ratified on November 12th, 1940. According to the federal census of that year, the county population numbered 57,544 in 1940. Nearly $1,000,000 worth of new construction had been authorized in 1939, showing that although the decade had started in tough times, it was widely assumed that things were on the upswing for the 1940s to follow. However, an overseas war would require unity and sacrifice here at home. The building and Real Estate business in Frederick and elsewhere would slow considerably under the demands and hardships of World War II. Personal Property Rights Throughout its first decade, the Frederick Real Estate Board had marketed the benefits of home and business property ownership. Regular newspaper ads stressed the freedom to buy, sell, and utilize property, as protected by the law of eminent domain found within the Fifth Amendment of the US Constitution. This continues to underlie real estate transactions and markets. A foundational tenet for all Realtors® of today states: “Any restrictions placed on a property owner from realizing the highest, and best, use of that property hinders economic growth and development while reducing freedoms inherent in our society.” Of course, these opportunities have served in addressing residential and commercial needs and provided economic impact for both Frederick City and County over the last century. Federal and state-controlled rent controls were begun during the Great Depression era of the 1930s. Dating back to the late 1930s, the Board of Real Estate opposed federal housing proposed for Frederick which fostered in their words, “political landlordism.” The organization sought opportunities for non-government housing accommodations to be created on behalf of those in need of affordable rental units. This challenge still lingered for the African American community as Frederick was no stranger to segregation. Here in Frederick, a local housing project had been given final approval by the Federal Housing Authority in December 1939. Work started on this project given the working name of the “colored housing project” and took place on Phebus Avenue and DeGrange Street in May of 1940 with demolition of several existing slum tenements. This project would become known as the Lincoln Apartments and opened in 1941. Meanwhile, another project called “the white housing project” would break ground in the northern reaches of the city in the environs of Klinehart’s Alley at 5th, 6th and 7th streets. This would take the name of the Roger Brooke Taney Apartments and opened in 1942.  In time, other housing projects such as the John Hanson Apartments, Sagner and Carver Apartments would be constructed here by the federal government. Speaking of the federal government, additional federal, state and local controls would be ushered in on account of the impending World War. The Office of Price Administration (OPA) was established within the Office for Emergency Management of the United States government by Executive Order on August 28th, 1941. The functions of the OPA were originally to control money (price controls) and rents after the outbreak of World War II. This became a key issue for Frederick’s Board of Real Estate and President Howard Gross who would serve in this role for six consecutive years from 1941-1946. The practice of price controlling tended to discourage home building and ownership among other things. A tireless lobbying and education campaign by Frederick’s local Real Estate Board eventually overturned state and federal rent controls, giving the right of property owners to control rents charged. These controls began in 1944 but would stay in play here in Frederick well after the war’s end in 1945. The problems associated with OPA rent controls persisted, prompting Frederick’s Real Estate Board to place a large advertisement in the local paper in February of 1947. This ad explained that housing was almost non-existent because OPA rent controls had forced the sale of antiquated rental units to former tenants at high prices caused by heads of families outbidding one another. The ad urged resistance to the establishment of a Maryland Rent Control Commission. The Office of Price Administration was abolished two months later on May 29th, 1947, by the General Liquidation Order issued March 14th, 1947, by the OPA Administrator. Unfortunately, extensions would continue leading the Maryland Rent Control Commission and local jurisdictions like Frederick to not abolish these controls for years amidst great opposition by organizations such as the Landlords’ Association of Frederick City, backed by the Real Estate Board of Frederick. Another large advertisement was purchased and urged, “Let war time Federal Rent Control die on March 31, 1949.” Another two years would pass until pointed arguments were aired during a special meeting called at the request of the Real Estate Board of Frederick which included Frederick City Mayor Elmer F. Munshower and the Board of Aldermen. This occurred in May of 1951. Local government authorities under the name of the Frederick Rent Control Board held firm claiming that “further continuation of Rent Control in the Frederick Defense Rental Area will not serve the purpose of protecting the tenant and the community interest but has actually been harmful to tenant interest inasmuch as it has resulted in a substantial shrinkage in the rental market.” In their argument, the landlords included the fact that rent controls tend to discourage home building and home ownership. They also said that controls tended to create slums, due to landlords’ inability to repair and maintain properties. Another key point argued that controls reduce values of real estate and, consequently, the taxing authorities must place lower assessments on properties. Echoing their consistent and unified message, members of the Real Estate Board contended that rent control locally “had failed to protect the interest of the tenant inasmuch as controlled property is rapidly disappearing from the market through sales, withdrawal for other reasons and refusal to rent.” They added, “Tenants displaced by sales have in many instances been compelled to purchase at inflated prices.“ Lastly, the Board said, “Controls have materially reduced construction of new rental units and the net result has been detrimental to the interests of the tenants and the community.” The controls would persist until August 1st, 1953—a period of nine years. The Board of Real Estate remained vigilant throughout the fight. Irony lies in the fact that the head of rent control in the eastern and central sections of the United States under President Harry S. Truman was a man named Howell C. Happ, Sr. Mr. Happ lived at Gapland atop Catoctin Mountain, adjacent Burkittsville in the once, majestic estate built by George Alfred Townsend after the Civil War. Happ’s son, Howell C. Happ, Jr. would later serve as Frederick County’s Board of REALTORS® president from 1972-73, and that gentleman’s wife, Shirley L. (Baker) Happ, would serve as president from 1975-76. Speaking of fights, World War II had the initial effect of ushering in these rent controls, as said earlier, but the recent war would also change the residential fabric of Frederick forever. The best-known “baby boom” is considered to have started after the end of the Second World War, lasting from 1946–1964. In the US, the number of annual births exceeded 2 per 100 women (or approximately 1% of the total population size) with an estimated 78.3 million Americans born during this period. The population of Frederick County grew from 57,312 in 1940 to 62,287 in 1950, and 71,930 in 1960. The war also brought new residents to Frederick in respect to taking, or being assigned to, government jobs at Frederick’s local military installation centered in the county seat. The Detrick Effect Late 1941 saw the US enter war against Japan, and, eventually, with Nazi Germany. The federal government took an active interest in Detrick Field, west of Villa Estates out Rosemont Avenue. With humble beginnings as an emergency landing field three decades earlier, the airport was made into a permanent training field for the annual encampment of the 104th Aero Squadron of the 29th Division (MD National Guard). The field was named after Dr. Frederick L. Detrick, flight surgeon of the unit. Detrick was a Frederick native who served in France during World War I as a surgeon.  Shortly after the Pearl Harbor attack, men and women from across the nation were assigned here. Many were military personnel, but hundreds were scientists. Most of these newcomers were assigned to top-secret projects, about which little was known. A glimpse of what the government employees were working on was given April 10th, 1943, when Detrick Field officially became Camp Detrick under the US Army Chemical Warfare Service. Many of these people required off-base housing and many began purchasing lots in the nearby suburban Frederick area and began building homes. The unified war effort understandably slowed the construction boom of the late 1930s here in Frederick and all over the country. However, peace would return in 1945 as both foes surrendered. When veterans returned home from overseas, they found jobs plentiful. Many were employed at Camp Detrick, while others found jobs at new industries located in the county. Those people who came to Camp Detrick during the war remained, and these new residents helped boost the Frederick County economy for the next two decades. These people bought houses, raised families and took part in Frederick civic and social affairs truly adding to the community fabric in leadership roles, etc. In 1956, the camp would be renamed Fort Detrick and designated a permanent army installation. This new influx of residents bought and built homes in the existing subdivisions on the northwest part of town near the base. Others were moving to Frederick because of improvements in travel with the construction of US 15, which stretched like a spine across the center of the county from Emmitsburg and the Mason-Dixon Line in north county, to Point of Rocks and the bridge over the Potomac to Loudoun County, VA in the southern part. All the while, a few new developments would continue to spring up in the form of Saratoga, and College Estates. Saratoga began in 1952 and was positioned south of West Patrick Street and west of Catoctin Terrace to the new highway and Linden Hills further out. Interestingly, this development encountered a name change in 1954 due to the popularity of a motion picture. It would go from Saratoga to “Brigadoon.” A special name-changing ceremony helped usher in this special request made by residents. College Estates was built north of Villa Estates and West 7th Street. This subdivision offered a more economical alternative option to potential property buyers and was another good choice for Detrick personnel as it was just outside the east gate and sandwiched between Detrick and US15 to the east. Assessing growth by the mid-1950s, Frederick had changed considerably over the three decades of existence of the Real Estate Board of Frederick. Only one of the original Board directors (Markell Nelson) was still alive, but others would carry the torch of the organization’s founding mission and principles. Along the way, Frederick’s Real Estate Board had grown in number, while maturing into one of the leading and most respected organizations in the state. The group was poised and ready for the next 70 years in which Frederick County’s population would more than quadruple in size. ***Be sure to check out parts 1 & 3 of the centennial history of Frederick County Association of REALTORS® (Click below)

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorChris Haugh Archives

February 2024

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed