HSP HISTORY Blog |

Interesting Frederick, Maryland tidbits and musings .

|

|

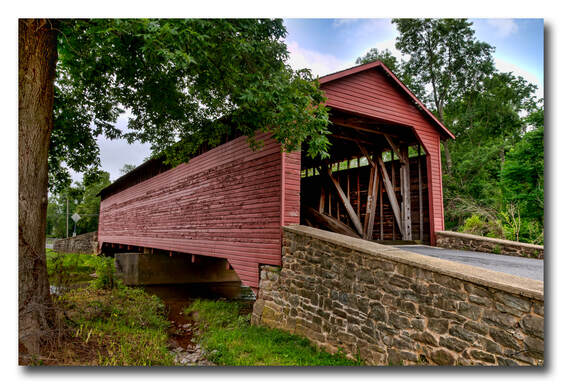

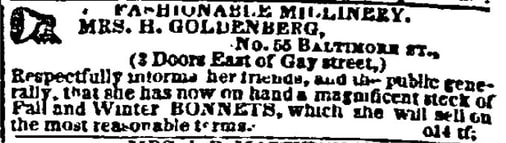

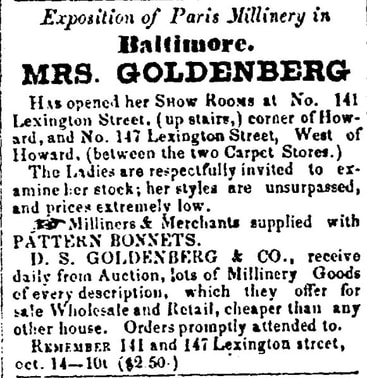

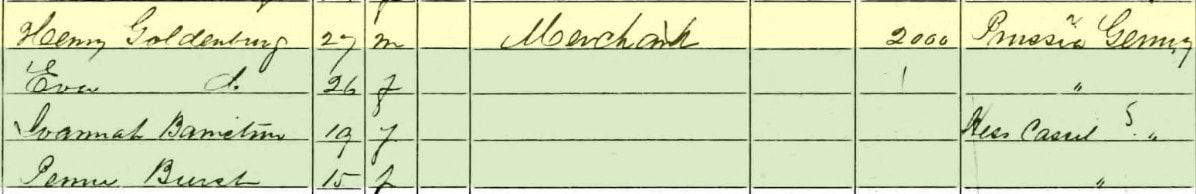

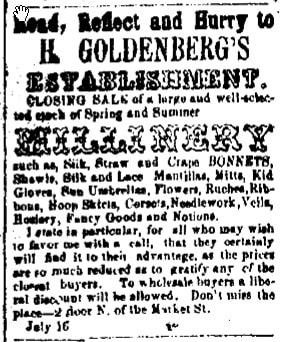

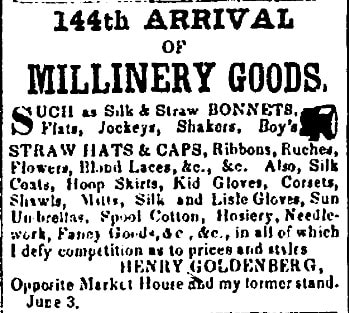

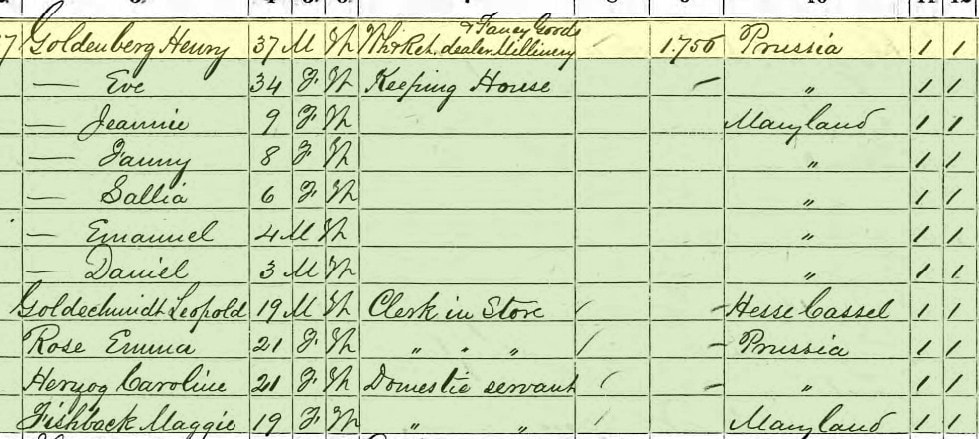

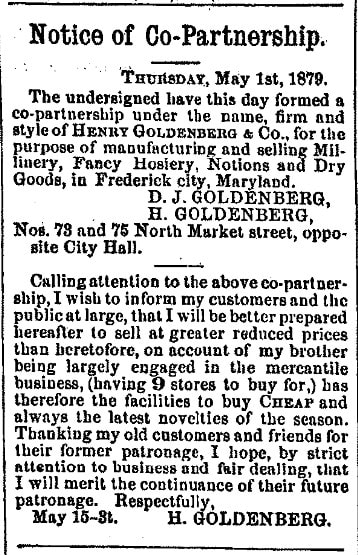

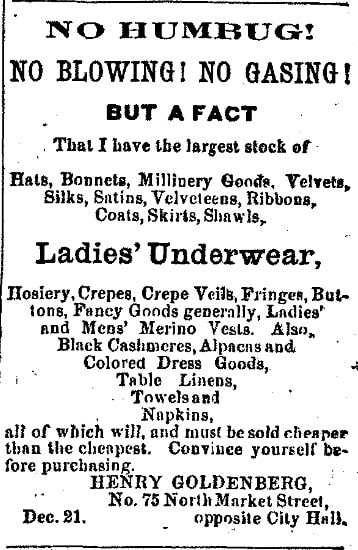

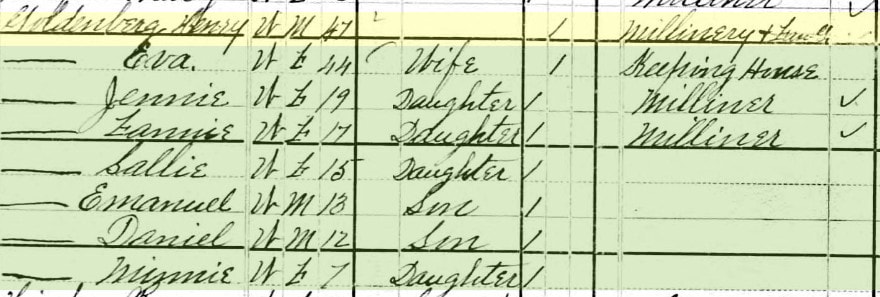

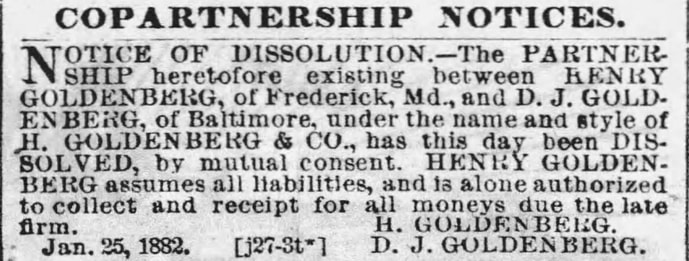

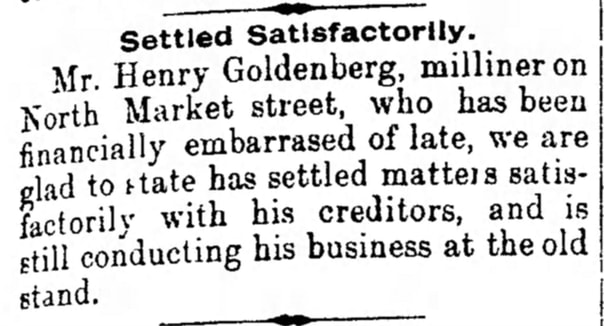

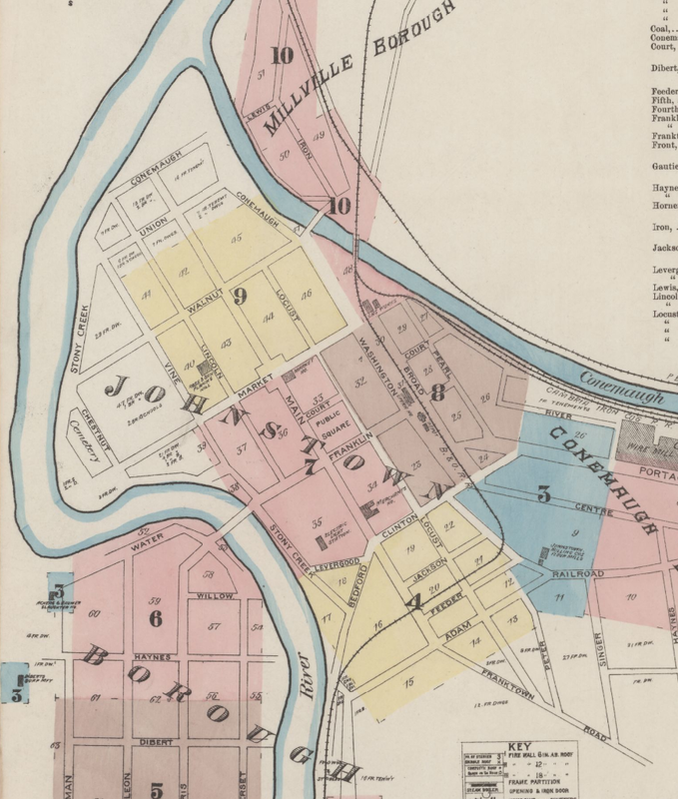

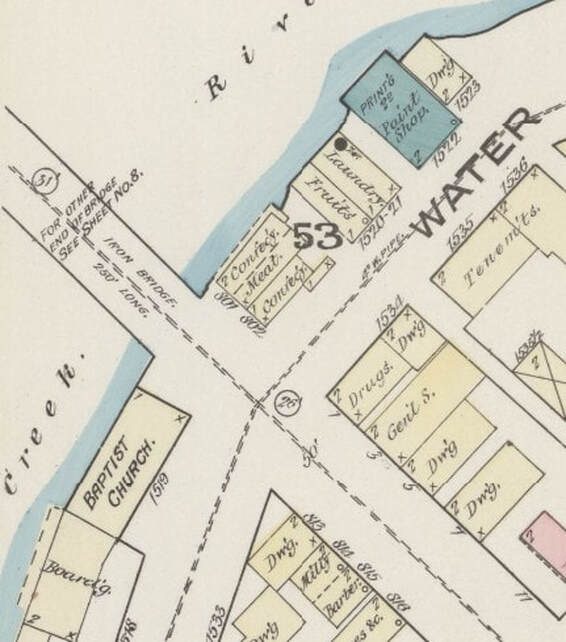

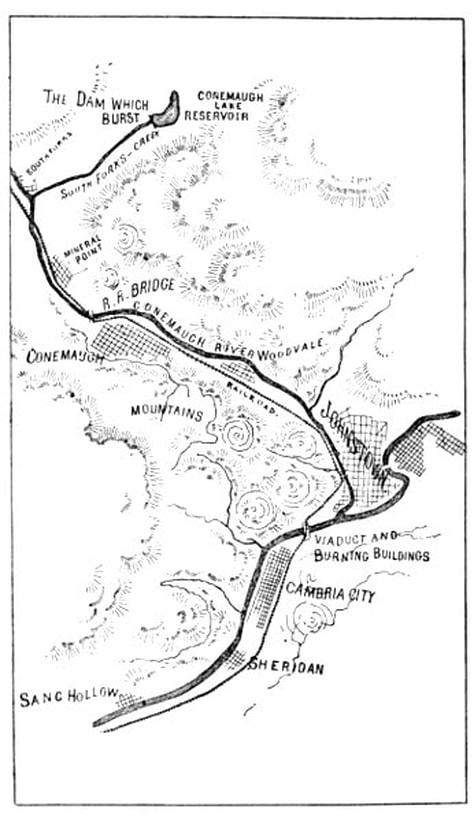

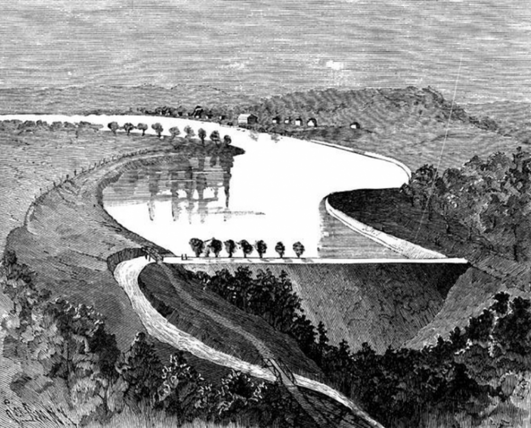

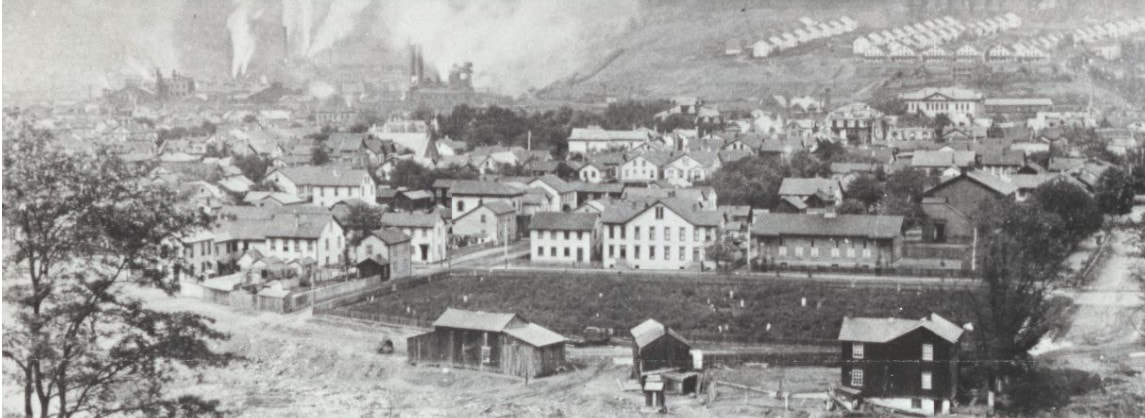

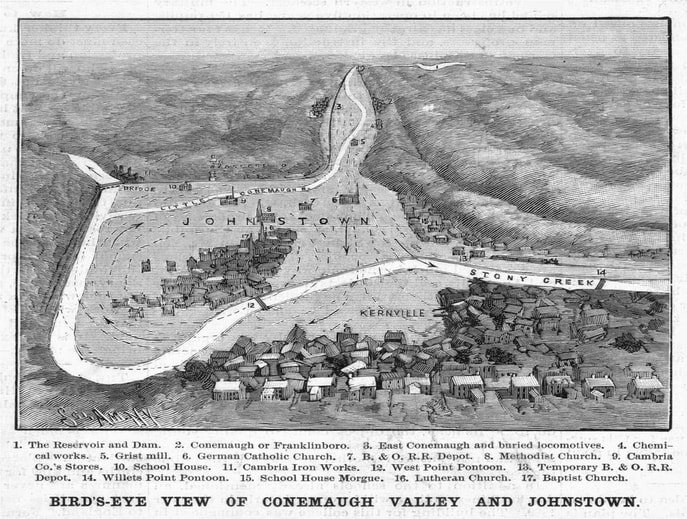

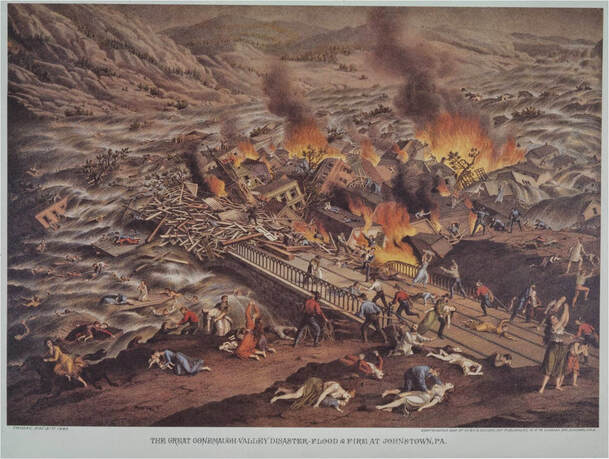

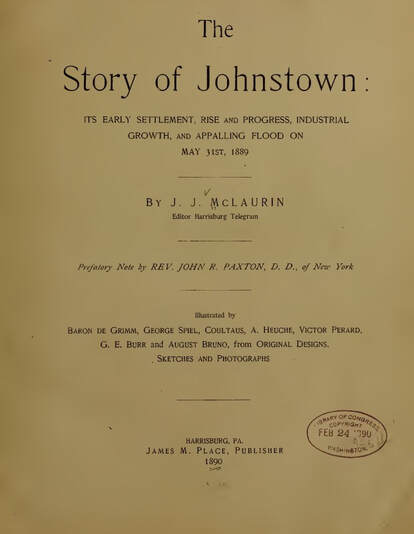

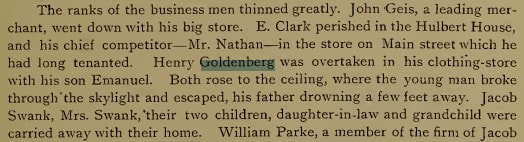

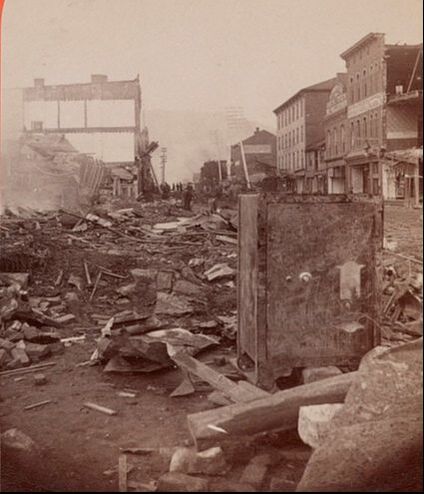

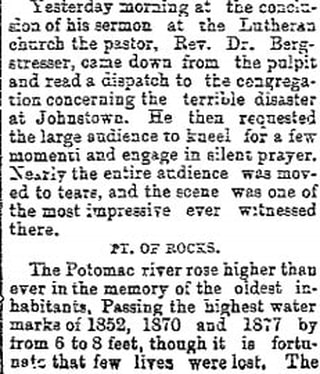

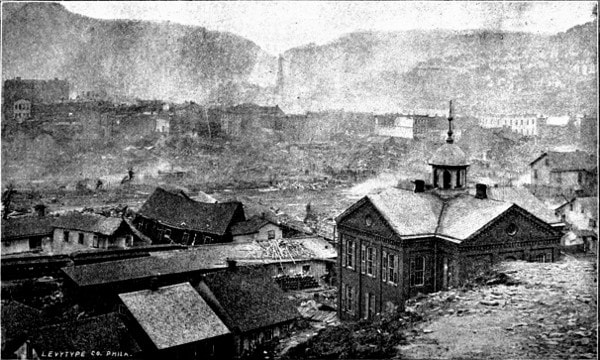

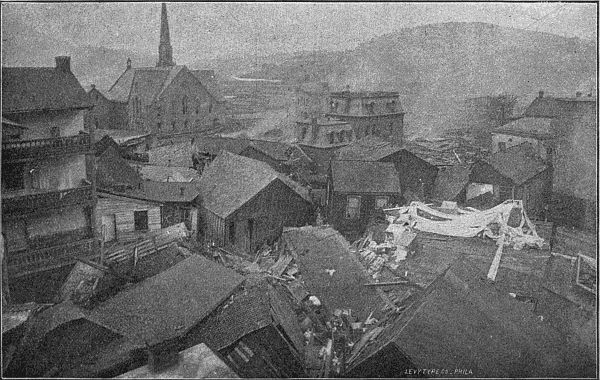

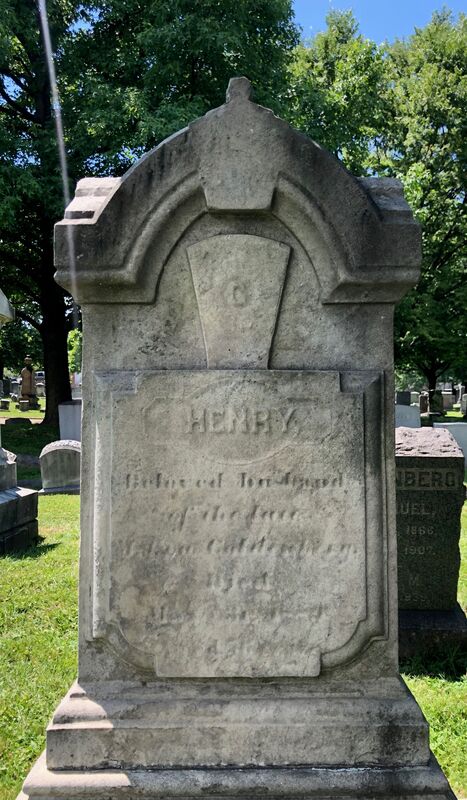

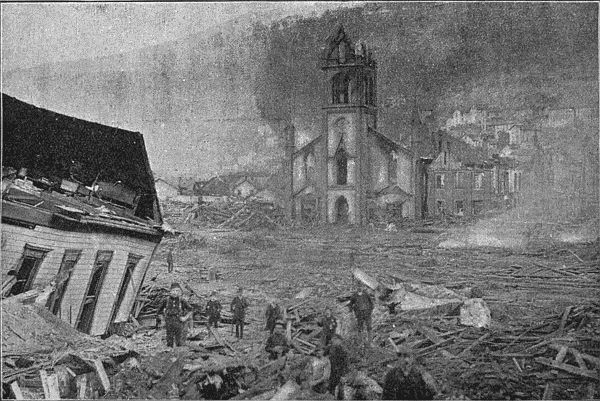

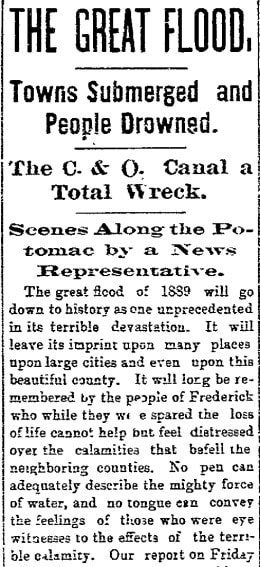

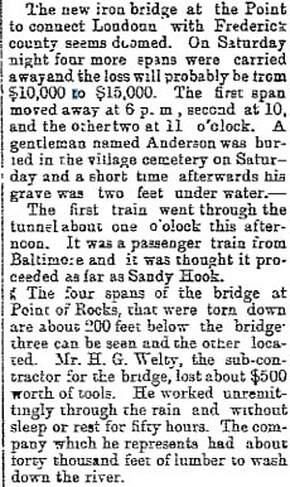

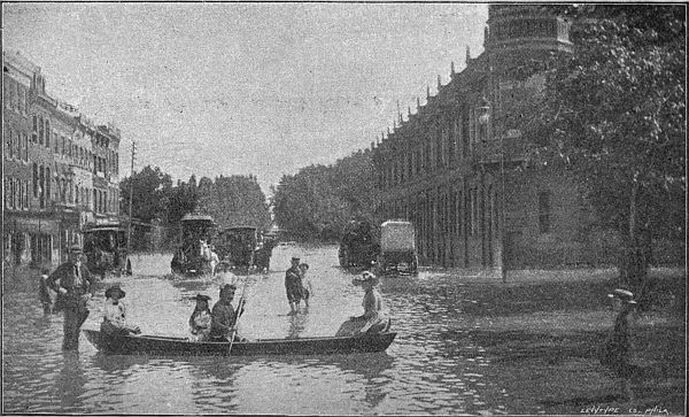

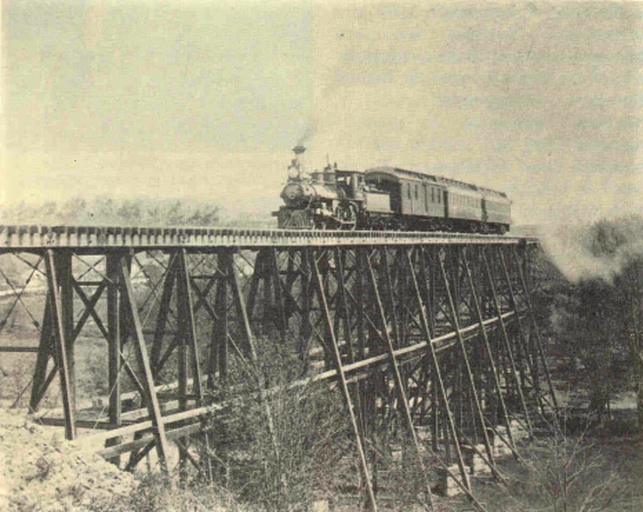

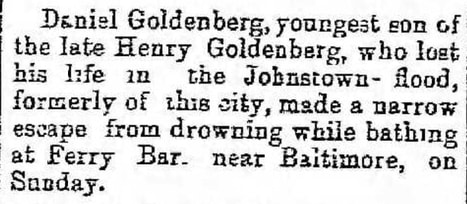

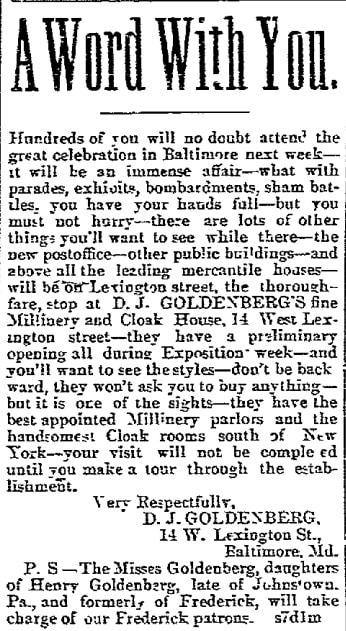

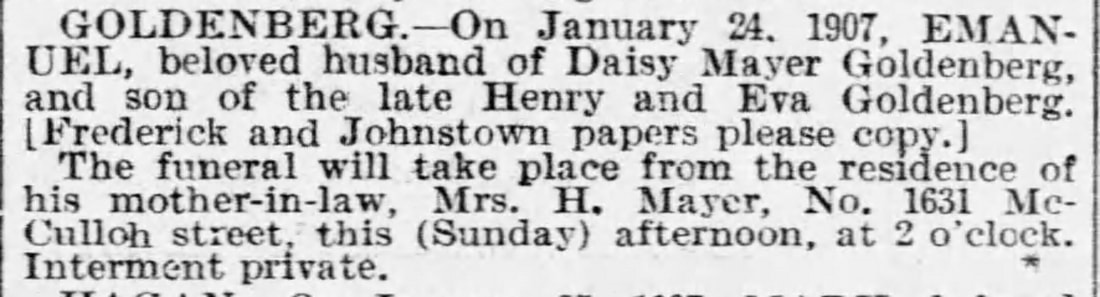

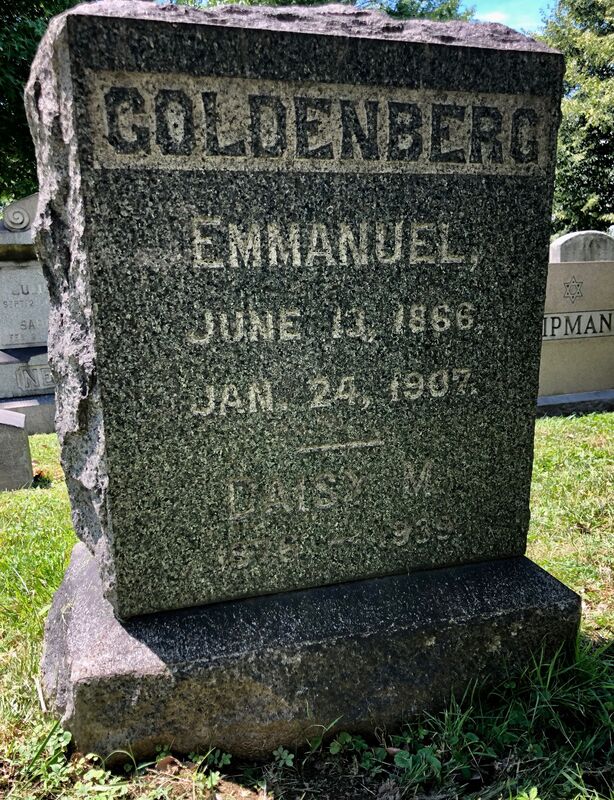

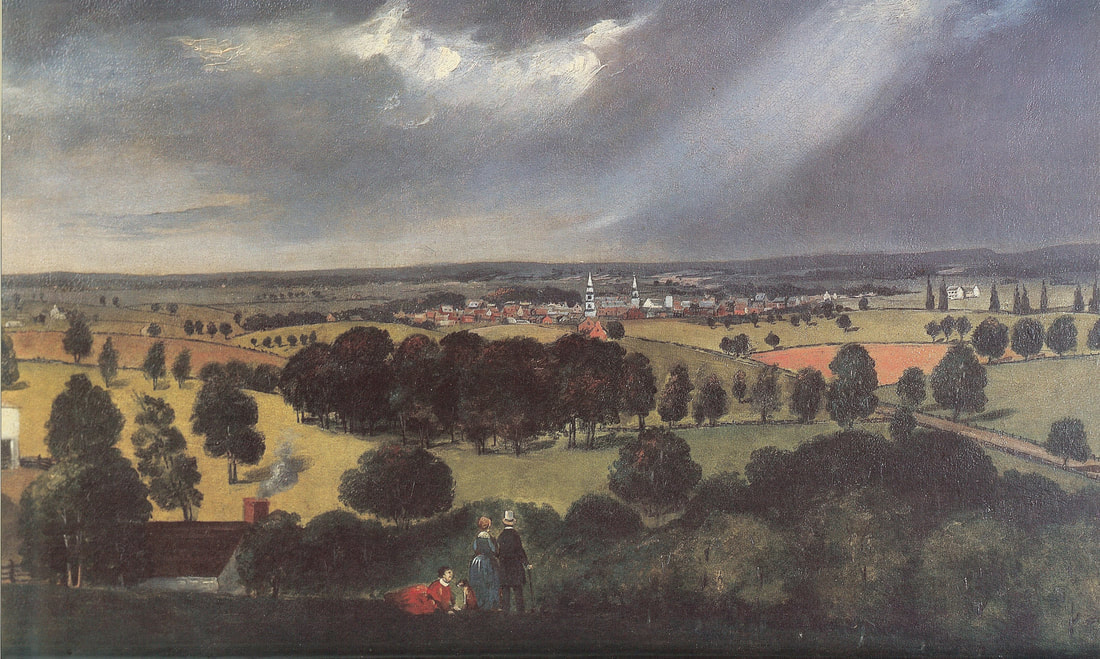

“Being at the wrong place at the wrong time,” an expression we hear quite often when a hapless victim encounters a tragic event that many times leads to serious injury or, worse yet, death. My full-time job is that of a historian for a cemetery, so you can imagine I think of the fore-mentioned saying a lot. One of the best examples I’ve come across involves a prominent Frederick businessman in the mid-1800s named Henry Goldenberg. Five years after his move from Frederick in the year 1884, Mr. Goldenberg would meet a fateful end in one of the country’s worst-ever disasters. It happened in a bustling town in western Pennsylvania. Born in 1833, Henry Goldenberg was born and raised in Neheim, a town of Prussian Westphalia, located ten miles northwest of current-day Arnsberg, Germany. His parents, Jacob Goldenberg and wife Rachel (Rose) Goldenberg, left a country in turmoil and came to America in 1852 with their eight children. They would settle in Baltimore’s 7th Ward, northeast of the inner harbor in the vicinity of Johns Hopkins University and Medical Center. Early advertisements appear in the Baltimore newspapers touting the millinery expertise of a Mrs. H. Goldenberg in the Ward 7 sector of Charm City. Henry’s brother, Daniel Joseph (Goldenberg), is mentioned in connection here, and would be linked to Henry's business endeavors for decades to come. Four years later (1857), the following advertisement appeared in the Frederick Examiner newspaper touting Mrs. Goldenberg’s talents. Henry Goldenberg would soon be living in Frederick with his wife, the former Mary Eva Nardhaus, also a native of Prussia. Henry moved to town permanently in 1859 and opened his shop on the east side of North Market Street between the old Market House building (today’s site of Brewer’s Alley Restaurant) and Second Street. This was formerly the site of Michael Engelbrecht’s tailoring shop. The location is today under Market Alley which runs along the north of Brewer’s Alley Restaurant. This time period would mark an important era in Frederick’s Jewish history as the Goldenbergs and other Jewish families from Baltimore (like David Lowenstein and Jacob Rosenstock) would settle here and open clothing and other businesses.  Looking north on North Market Street midway between Church and 2nd streets. This photo dates to February, 1862 and a military display by Union troops in honor of George Washington's birthday. On the right side of the street is pictured the Market House to the immediate north of Andrew Boyd's awning shown here. The Goldenberg's store/home was two doors to the north. Mr. Goldenberg is mentioned in the writings of the brother of the above-mentioned Michael Engelbrecht. This was Frederick’s loquacious diarist, Jacob Engelbrecht (1898-1878). In that same year of 1859, he wrote: “Mr. Henry Goldenberg voted today at the Market house polls for the first time. He was naturalized on the 11th day of October 1859 in the Court of Common Pleas of Baltimore City. William Lee, Marshall, Thomas Creamer, Sheriff, William J. Hamill, Clerk.” Engelbrecht took a liking to Henry as they were both in the clothing business (Engelbrecht was a tailor by trade) and both had deep German roots. As if it wasn’t a challenge enough to open a new business in a new town, the Goldenbergs had to navigate through the American Civil War and Frederick’s major role played within it. Henry Goldenberg showed fellow residents his patriotic colors by participating as a member of the Brengle Home Guards in April 1861. The local militia group soon found themselves performing important roles of protecting Maryland’s governor (Thomas Hollyday Hicks) and state legislators convened here throughout the summer of 1861 and meeting at Kemp Hall (SE corner of N. Market and E. Church streets) instead of the State House in Annapolis. Henry Goldenberg’s military service would not extend to the US Army, although he registered for the draft. He continued to serve the community through his mercantile endeavor. Goldenberg evolved into a spectacular marketing guru, with his plentiful ads filling the pages of early Frederick newspapers of the era. From at least 1859 until Dec 1861, there had been a Goldenberg & Company located "2 doors N of Market House.” In 1861 Henry bought the stock of goods from the store room of another brother named Julius Goldenberg. Julius was described in the deed as trading under the name of Goldenberg & Company in dry goods, fancy and millinery goods. Julius had become indebted to Henry on 3 due bills given to Henry for wages owed him as clerk in the store – in August 1859 for $225, August 1860 for $270 and June 1861 for $220. So for that $715 owed, and another $500 cash, Julius sold Henry the stock and good will of the establishment. A new location for the family business would come about as the Goldenberg millinery and fancy goods store would locate across the street from its original location. The move wasn't far as the new setting was exactly across Market Street from the Market House (which would be soon razed and the new City Hall and Opera House would be built on its site.) The Goldenberg endeavor would have an address of 73 and 75 N. Market Street. The property was rented to him by Margaret Engelbrecht, widow of John Engelbrecht, another sibling of the diarist Jacob. Of additional interest, Goldenberg was reported to have had one of the first open storefronts of any business in town. Since no other property records, outside of these store locations, link to the Goldenberg family, I’m assuming they lived in the same sites as the business locations. My research assistant, Marilyn Veek, only found one real deed associated with the Goldenberg family. This was a one square-foot piece that Henry bought in 1877 from William Kline, along with a 1-inch right of way, which was behind what is now Asiana Restaurant and not next to the store he actually rented for his business. What was this all about? Henry Goldenberg further vested himself in civic functions and social organizations of town. Of key interest was his involvement in Frederick’s Masonic Lodge and would serve in various leadership roles. Things seemed to be going good, and in 1879, Henry joined forces with fore-mentioned brother Daniel Joseph Goldenberg of Baltimore in a business partnership. Something went seriously wrong in the first few years of the 1880s for the Goldenbergs. In 1882, advertisements announce the dissolution of the partnership between Henry and his brother, Daniel. I haven’t figured out all the details but D. J. Goldenberg encountered a major setback when a fire destroyed his location on Lexington Street in Baltimore. This seems to have had an impact on the Frederick (MD) Goldenbergs as a newspaper ad in the local paper in 1883 seems to paint a rather gloomy outlook for the discount Millinery business-owners. In 1883, Henry signed a deed of trust with his brother-in-law Philip Stern to sell all of his stock in trade and fixtures in the store room occupied by him on N. Market and all his other property, to pay off his creditors, as well as taxes due and salaries due to his employees. This implies that the store still existed until 1883. (Note: A newspaper article in 1885 mentions that Philip Stern for several years conducted a notion and ladies store on Market St, but now intends to quit business and remove from Frederick, so maybe Philip took over the store.) In early 1884, the Goldenbergs time in Frederick was up. They chose to head west and put into motion an opportunity in Pennsylvania and a boom town located some 70 miles east of Pittsburgh. With two sisters living in Altoona, the Goldenbergs chose to reside in Johnstown in Cambria County. Johnstown, Pennsylvania was settled in 1770 by Swiss German settlers at the intersection of the Conemaugh River which split into the Little Conemaugh River to the east east and Stoneycreek River flowing south. A century later, the small village grew into a bustling town thanks to the success of the Cambria Iron Works. Henry Goldenberg took up residence at 54 Lincoln Street. By help of an 1886 Sanborn Insurance map, I have a strong hunch that the Goldenberg Millinery store was located across Stoneycreek River from their residence in the first block of Morris Street in the southwest portion of town. Although firmly transplanted in his new home in Johnstown, Henry and other family members never lost their love for Frederick. The first big blow to the family came in August 1885 with the death of Henry’s wife, Mary Eva. Her body would be sent back to Baltimore for burial at Hebrew Friendship Cemetery. The family pulled together and moved forward without Mrs. Goldenberg. Everything was going swimmingly, probably not the best term to use, until 4:07pm on May 31st, 1889. One day earlier, on the afternoon of May 30th, 1889, it began raining in the Conemaugh Valley, but luckily Johnstown had just managed a quiet Memorial Day ceremony and parade earlier in the day. Twenty-four hours later, water filled the streets of a town that was certainly no stranger to annual flooding. However, this time things were a vastly different. As rumors had swirled that a dam holding an artificial lake in the mountains to the northeast might give way, the ill-fated prophecy would come true on this dark day. The South Fork Dam collapsed 14 miles upstream from Johnstown due to the heavy rains. In the process, an estimated 20 million tons of water began spilling into the winding gorge that surrounded the Little Conemaugh River as it led to Johnstown. Historians claim that the force barreling toward Johnstown had a volumetric flow rate that temporarily equaled the average flow rate of the Mississippi River. A massive tragedy would strike the town and its unknowing residents downstream in ten minutes time. What had been a thriving steel town with homes, churches, saloons, a library, a railroad station, electric street lights, a roller rink, and two opera houses was buried under mud and debris. Out of a population of approximately 30,000 at the time, at least 2,209 people are known to have perished in the disaster. One of the most graphic descriptions of the carnage experienced in Johnstown can be found on the National Park Service’s memorial: “But at 4:07pm on the chilly, wet afternoon of May 31, the inhabitants heard a low rumble that grew to a “roar like thunder.” Some knew immediately what had happened: after a night of heavy rains, the South Fork Dam had finally broken, sending 20 million tons of water crashing down the narrow valley. Most never saw anything until the 36-foot wall of water, already boiling with huge chunks of debris, rolled over them at 40 miles per hour, consuming everything in its path. Those who did see it said it “snapped off trees like pipestems,” “crushed houses like eggshells,” and “threw around locomotives like so much chaff.” A violent wind preceded it, blowing down small buildings. Making the wave even more terrifying was the black pall of smoke and steam that hung over it—“the death mist” remembered by survivors. Thousands of people desperately tried to escape the wave, but they were slowed as in a nightmare by the 2 to 7 feet of water already covering parts of town. One observer from a hill above the town said the streets “grew black with people running for their lives.” Some remembered reaching the hills and pulling themselves out of the flood path seconds before it overtook them. Those caught by the wave found themselves swept up in a torrent of oily, yellow-brown water, surrounded by tons of grinding debris, which crushed some, provided rafts for others. Many became helplessly entangled in miles of barbed wire from a destroyed wire works. People inside when the wave struck raced upstairs seconds ahead of the rising water, which reached the third story in many buildings. Some never had a chance, as homes were immediately crushed or ripped from foundations and added to the churning rubble, ending up hundreds of yards away. Everywhere people were hanging from rafters or clinging to rooftops and railcars being swept downstream, frantically trying to keep their balance as their rafts pitched in the flood. It was over in 10 minutes, but for some the worst was still to come. Thousands of people, huddled in attics or on the roofs of buildings that had withstood the initial wave, were still threatened by the 20-foot current tearing at the buildings and jamming tons of debris against them. In the growing darkness, they watched the other buildings being pulled down, not knowing if theirs would last the night. But the most harrowing experience for hundreds came at the old stone railroad bridge below the junction of the rivers. There, thousands of tons of debris scraped from the valley, along with a good part of Johnstown, piled up against the arches. The 45-acre mass held buildings, machinery, hundreds of freight cars, 50 miles of track, bridge sections, boilers, telephone poles, trees, animals, and 500-600 humans. The oil-soaked jam was immovable, held against the bridge by the powerful current and bound tight by the barbed wire. Those who were able began scrambling over the heap toward shore. But many were trapped in the wreckage, some still hopelessly hung up in the barbed wire, unable to move. Then the oil caught fire. As rescuers worked in the dark to free people, the flames spread over the whole mass, burning with “all the fury of hell.” One of the unfortunate victims was none other than Frederick’s former resident, Henry Goldenberg. A book entitled The Story of Johnstown was written in 1889 by J.J. McLaurin. The author received information about Frederick’s former resident. The news reached Baltimore and Henry’s brother D. J. Goldenberg before it hit Frederick shortly thereafter. Mr. D. J. Goldenberg, of 727 West Lexington street, has received a peculiar dispatch about his nine relatives at Johnstown. It reads: "At Rockwood with corpse; will be delayed at Cumberland." This is signed "Jennie Goldenberg." His anxiety is very great as to the identity of the only one who succumbed to the elements. His relatives are: Henry Goldenberg, a brother, formerly of Frederick, Md.; the latter's four daughters, (the youngest aged 16) and two sons. Mrs. Phillip Stern, of Frederick, Md., a sister, together with a sister-in-law, Mrs. Jos. Goldenberg of Philadelphia, were on a visit to Mr. H. Goldenberg and are therefore in the flooded district. Mr. D. J. Goldenberg, of this city, received a telegram yesterday, dated Rockwood, Pa., from his niece, Miss Jennie Goldenberg stating that she was on her way to Baltimore with the body of her father, Henry Goldenberg, who is Mr. Goldenberg's brother, and who was killed in the Johnstown disaster. He was a native of Germany and had been in America for about thirty-five years. For thirty years he had been a resident of Frederick, moving to Johnstown about four years ago. He had four daughters and two sons, and it is not known how many of them are alive. The Baltimore Sun (June 3, 1889) Here is how the news of Henry Goldenberg’s death appeared to his old friends, neighbors and customers in Frederick.  Barton Barton The American Red Cross, led by Clara Barton and with 50 volunteers, undertook a major disaster relief effort. Support for victims came from all over the United States and 18 foreign countries. The Great Johnstown Flood of 1889 accounted for $17 million of damage (about $484 million in today’s dollars). After the flood, survivors suffered a series of legal defeats in their attempts to recover damages from the dam's owners. Public indignation at that failure prompted the development in American law changing a fault-based regime to one of strict liability. Interestingly, Frederick, itself suffered damage from the same weather system that led to the catastrophe that had transpired in western Pennsylvania. Meanwhile the Potomac, at the Point of Rocks, had overflowed into the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, and the two became one. It broke open the canal in a great many places, and lifting the barges up, shot them down stream at a rapid rate. Trunks of trees and small houses were torn from their places and swept onward.... A dozen lives lost, a hundred poor families homeless, and over $2,000,000 worth of property destroyed, is the brief but terrible record of the havoc caused by the floods in Maryland. Every river and mountain stream in the western half of the State has overflowed its banks, inundating villages and manufactories and laying waste thousands of acres of farm lands. The losses by wrecked bridges, washed-out roadbeds and landslides along the western division of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, from Baltimore to Johnstown, reach half a million dollars of more. The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, that political bone of contention and burden to Maryland, which has cost the State many millions, is a total wreck. The Potomac River, by the side of which the canal runs, from Williamsport, Md., to Georgetown, D. C., has swept away the locks, towpaths, bridges, and, in fact, everything connected with the canal. The probability is that the canal will not be restored, but that the canal bed will be sold to one of the railroads that have been trying to secure it for several years. The concern has never paid, and annually has increased its enormous debt to the State. At the mountain town of Frederick, Md., the Monocacy River, Carroll Creek and other streams combined in the work of destruction. Friday night was one of terror to the people of that section. The Monocacy River rose rapidly from the time the rain ceased until last night, when the waters began to fall. The back-water of the river extended to the eastern limit of the city, flooding everything in its path and riding over the fields with a fierce current that meant destruction to crops, fences and everything in its path. At the Pennsylvania Railroad bridge the river rose thirty feet above low-water mark. It submerged the floor of the bridge and at one time threatened it with destruction, but the breaking away of 300 feet of embankment on the north side of the bridge saved the structure. With the 300 feet of embankment went 300 feet of track. The heavy steel rails were twisted by the waters as if they had been wrenched in the jaws of a mammoth vise. The river at this point and for many miles along its course overflowed its banks to the width of a thousand feet, submerging the corn and wheat fields on either side and carrying everything before it. Just below the railroad bridge a large wooden turnpike bridge was snapped in two and carried down the tide. In this way a half-dozen turnpike bridges at various points along the river were carried away. The loss to the counties through the destruction of these bridges will foot up many thousand dollars.  Floodwaters swell the Monocacy at the bridge carrying Reichs Ford Road over the river near Pinecliff Park located southeast of Frederick City Floodwaters swell the Monocacy at the bridge carrying Reichs Ford Road over the river near Pinecliff Park located southeast of Frederick City Mrs. Charles McFadden and Miss Maggie Moore, of Taneytown, were drowned in their carriage while attempting to cross a swollen stream. The horse and vehicle were swept down the stream, and when found were lodged against a tree. Miss Moore was lying half-way out of the carriage, as though she had died in trying to extricate herself. Mrs. McFadden's body was found near the carriage. At Knoxville considerable damage was done, and at Point of Rocks people were compelled to seek the roofs of their houses and other places of safety. A family living on an island in the middle of the river, opposite the Point, fired off a gun as a signal of distress. They were with difficulty rescued. In Frederick county, Md., the losses aggregate $300,000. Monocacy Bridge: Probably one of the oldest landmarks in Frederick county bridges has gone down in the flood. The covered bridge on the Frederick and Liberty turnpike, supposed to have been the first one built here, bearing the date 1834. It stood the storms of over half a century, has never been rebuilt, but many repairs have been put upon it. This morning it went down with the raging current, making a total of six bridges gone along the Monocacy. One part of it is lying at Mr. Kefauver's and another at Mr. Hoke's.  Utica Mills Covered Bridge was also a victim of the storm that created the disastrous Johnstown Flood. It washed away a 250 foot, two span covered bridge over the Monocacy River on Devilbiss Road in Frederick County. One span of the bridge was saved, dismantled and two years later reconstructed as a 101' covered bridge on Utica Road, just off Frederick Road in Utica, Maryland over Fishing Creek. The original bridge is usually referred to as Devilbiss Road Covered Bridge. Most documentation shows the original bridge as constructed c1850, but many believe it was actually built in 1843. Although the bridge was moved from its location over the Monocacy, it still consists of original timber from the Devilbiss Bridge, so it retained its build date as 1843 and was renamed Utica Mills Covered Bridge. (Photo by Roger Lancaster on Flickr) Henry Goldenberg's son Daniel was living in Baltimore during the tragedy in Johnstown. Ironically, he almost became a drowning victim himself by evidence of this newspaper article in July, 1889. In the fall of 1889, D.J. Goldenberg, Henry's brother and former business partner, ran the following ad in the Frederick paper touting the fact that his late brother's daughters would help serve Frederick customers at a special sale at his Baltimore store location.

As for Johnstown, the citizenry, with aid from people, towns and companies from all over the country, rebuilt the town bigger and better than ever before. Another major flood occurred in 1936. Despite a pledge by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to make the city flood free, and subsequent work to do so, another major flood occurred in 1977. The 1977 flood—in what was to have been a "flood free" city—may have contributed to Johnstown's subsequent population decline and inability to attract new residents and businesses. To learn more, I've included this link to a seventh grader's video presentation which does a fine job in telling the complete story of the disaster. This came courtesy of the National Park Service.(Click Here for video) History Shark Productions Presents: Chris Haugh's "Frederick History 101" Are you interested in Frederick history?

Check out this author's latest, in-person, course offering: Chris Haugh's "Frederick History 101," with the inaugural session scheduled as a 4-part/week course on Monday evenings in June, 2023 (June 5, 12, 19, 26). These will take place from 6-8:30pm at Mount Olivet Cemetery's Key Chapel. Cost is $79 (includes 4 classes). For more info and course registration, click the button below! (More sessions to come)

4 Comments

|

AuthorChris Haugh Archives

February 2024

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed