HSP HISTORY Blog |

Interesting Frederick, Maryland tidbits and musings .

|

|

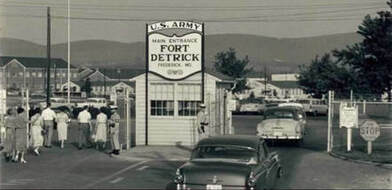

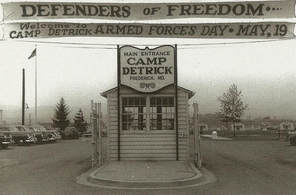

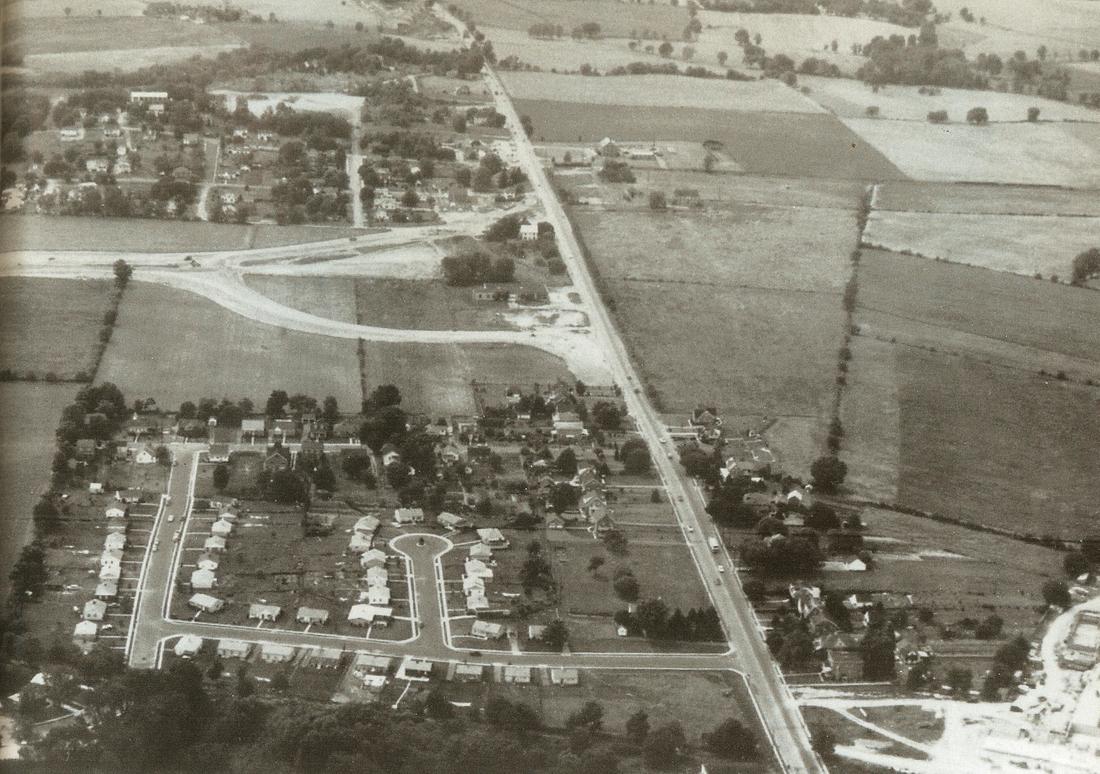

1959-1978  By the end of the 1950s, war-ravaged Europe had been re-constructed and began experiencing a tremendous economic boom. The United States and its allies had rebuilt their former foes into democracies based on the model of capitalism. Here at home, sluggish economic growth during the 1950s, would soon give way to another major boom in the 1960’s. World War II had brought about a huge leveling of social classes in which the remnants of the old feudal gentry disappeared, even here in Frederick. New residents from around the country, and world, had come to the area. This was primarily due to the growing importance of Camp Detrick, renamed Fort Detrick in 1956, and designated as a permanent installation for the US Army. Biological warfare experimentation continued to be researched here after World War II and throughout the Korean War to follow (1950-1953). Other projects underway involved scientists and support staff studying infectious diseases, cancer and genetic engineering. Some worked on developing better medical equipment and improving the environment. Detrick would also become the permanent site of the East Coast Relay Station in 1959, one of the key locations in America’s Defense Communications System, made all the more valuable during the Cold War period.  Other newcomers to Frederick County settled here as a result of the advent of commuting. The interstate highway system came about under President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Its importance stemmed originally from defense purposes, but it would soon revolutionize the nation by opening undeveloped areas throughout the country into new “suburbias.” High-speed superhighways allowed easy access to jobs centered in Baltimore, Washington, DC and Hagerstown. The expressway to the nation’s capital cut driving time in half, trimming a trip of roughly 80 minutes into one taking 40 minutes. On the local level, these roadways opened up new living opportunities throughout Frederick County. The automobile was the key lynchpin, allowing a degree of transportation freedom never experienced before. The economy of a nation benefited from the fruits of automobile makers.

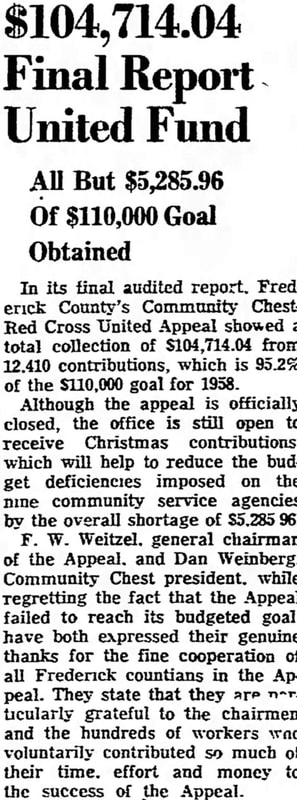

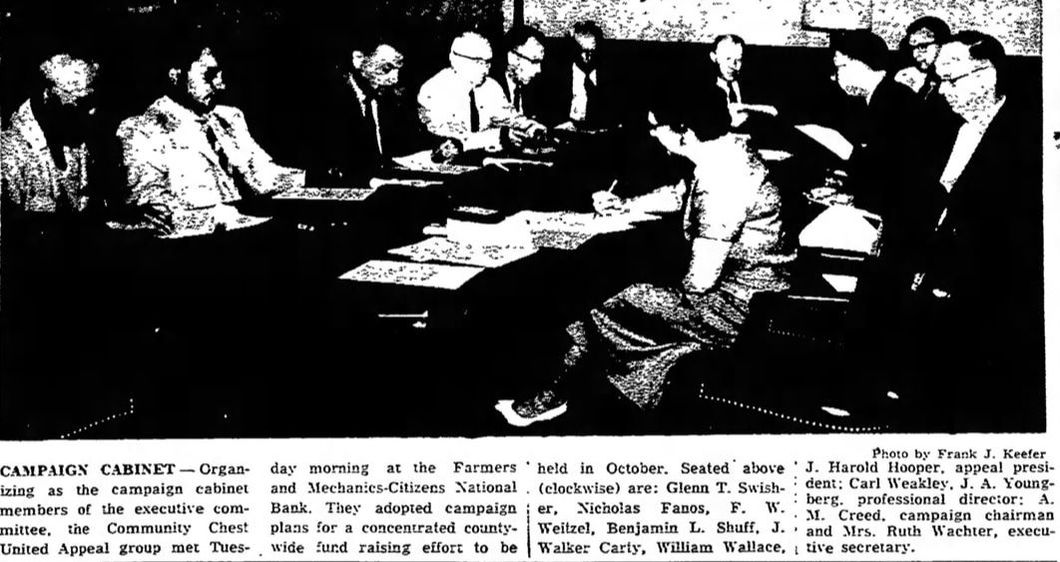

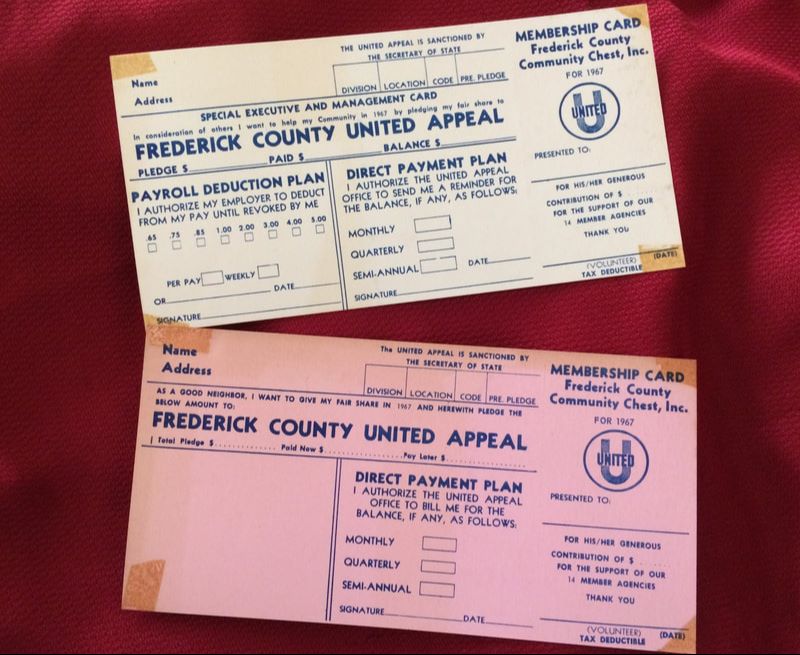

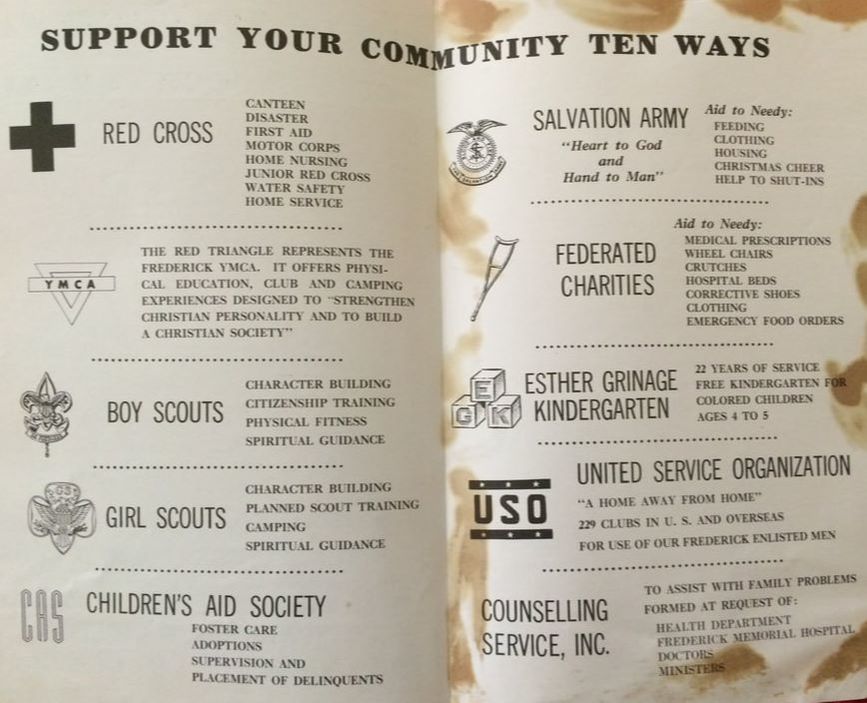

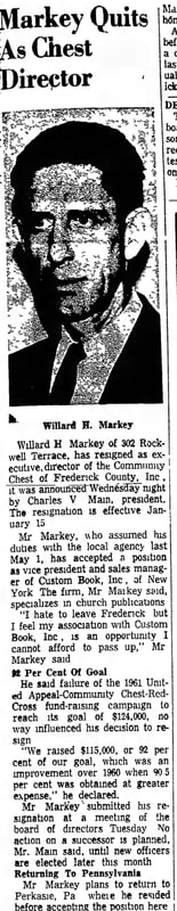

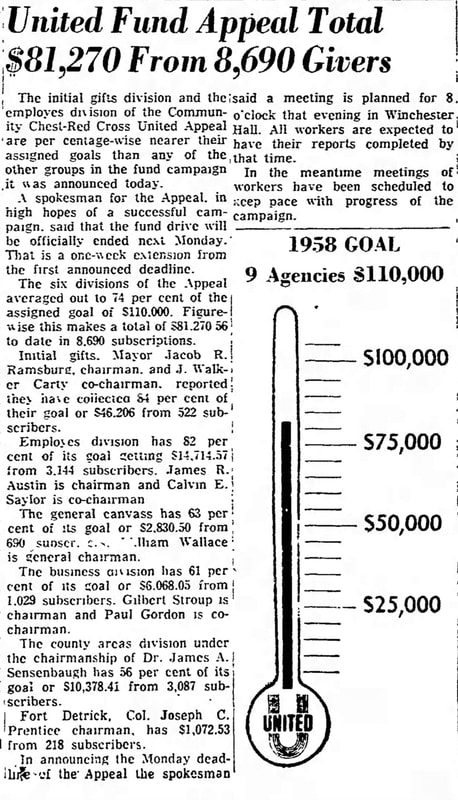

The 1950s decade ended with J. Harold Hooper at the helm of the Chest, and a campaign goal of $110,000 for the United Fund Appeal (between the Community Chest and American Red Cross). At this time, another local non-profit called Counseling Services, Inc. was admitted for membership. Meanwhile, a push was being made on the national, state and local level towards providing civil rights for all—underscoring racial equality for African-Americans. The post-war time of high economic growth and general prosperity became one in which African-Americans united and organized, and finally secured a triumph as the Civil Rights Movement ended Jim Crow segregation in the South. Frederick was the northernmost bastion of noted race inequality as it lingered directly below the famed Mason-Dixon Line. Here, schools, civic and social clubs, and restaurants would soon experienc desegregation. Further laws were passed that made discrimination illegal, and provided federal oversight to guarantee voting rights.  Despite the prosperity of the postwar era, a significant minority of Americans continued to live in poverty by the end of the 1950s. In 1947, 34% of all families earned less than $3,000/year, compared with 22.1% in 1960. Nevertheless, between one-fifth and one-fourth of the population could not survive on the income they earned. The older generation of Americans did not benefit as much from the postwar economic boom, especially since many had never recovered financially from the loss of their savings during the Great Depression. It was generally a given that the average 35-year-old in 1959 owned a better house and car than the average 65-year-old, who typically had nothing but a small Social Security pension for an income. Many blue-collar workers continued to live in poverty, with 30% of those employed in industry in 1958 receiving under $3,000/year. In addition, individuals who earned more than $10,000/year paid a lower proportion of their income in taxes than those who earned less than $2,000/year.  Chief Charles V. Main Chief Charles V. Main Blasting Off into the New Decade The continuing generosity of the community was needed, and by now, expected. The average goal of the United Fund Appeals through the decade (1960-1969) was $155,222 with average contributions and pledges totaling $146,025. The campaign, however, did not run itself. It was the solicitation for funds led by community leaders and tireless workers who unselfishly gave of their time, talent and energies. Among the guiding citizens of Frederick County's Community Chest during the 1960s era, we find the names of: Carl V. Weakley (Manager-C&P Telephone) Nicholas A. Fanos (President, Frederick Iron & Steel) Charles V. Main (Frederick City Police Chief) Raymond C. Brehaut (President, Frederick Natural Gas Co.) Jacob R. Ramsburg (Co-founder Frederick Underwriters & local/state politician) George A. Zeigler (MJ Grove Lime Co.) John R. Cheatham (Owner/Manager, Key Chevrolet) Dwight Collmus (Alex Brown & Sons) Francis W. Bush, Sr. (Dir. Of Safety/PR, MJ Grove Lime Co.) Paul J. Green (Manager, Farmers Supply Company) John C. Houston (Frederick Electronics Corporation) Charles M. Trubac (Vice-President, State Farm Insurance) James L. Rimler (CPA/Frederick County Auditor 1956-1963) James W. Freeman (President, Frederick Natural Gas Company)

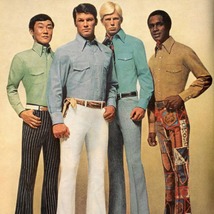

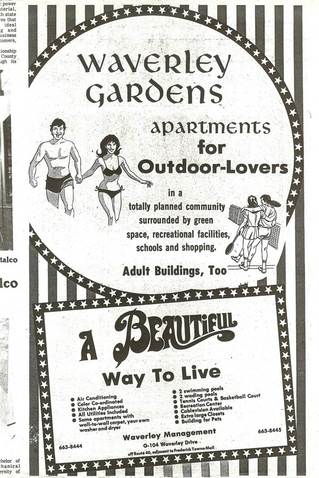

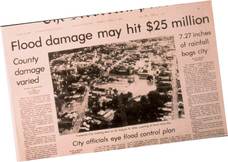

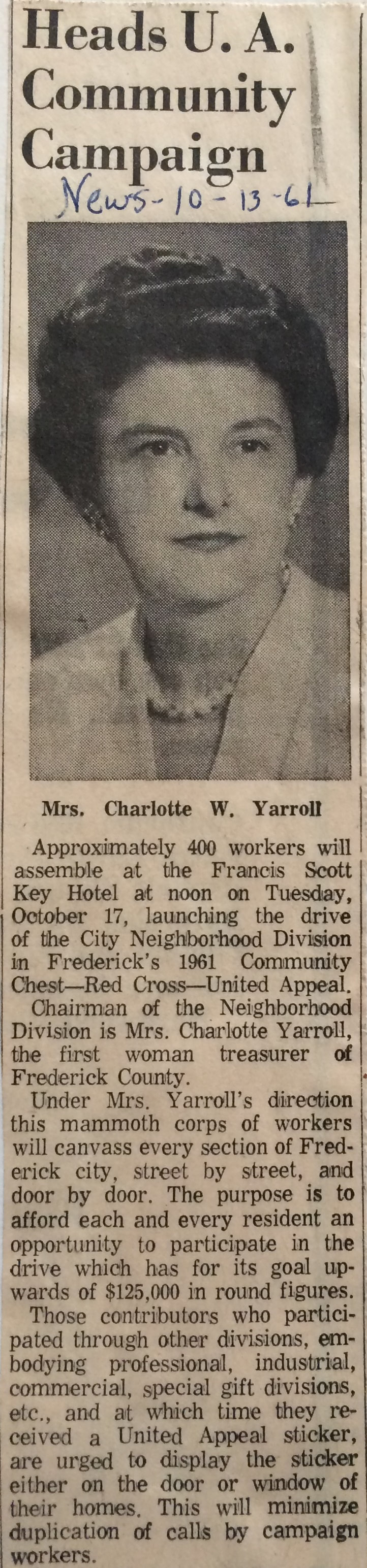

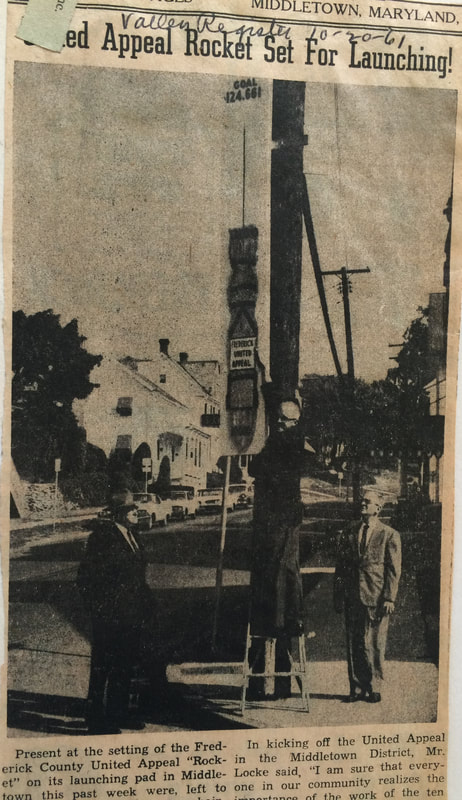

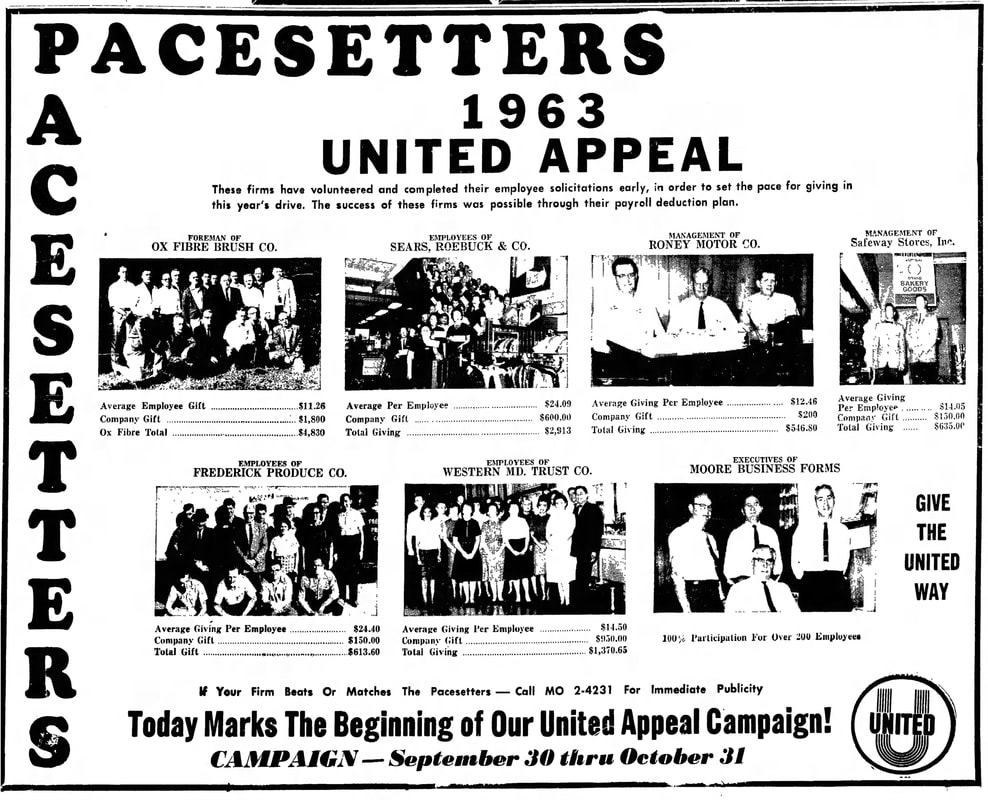

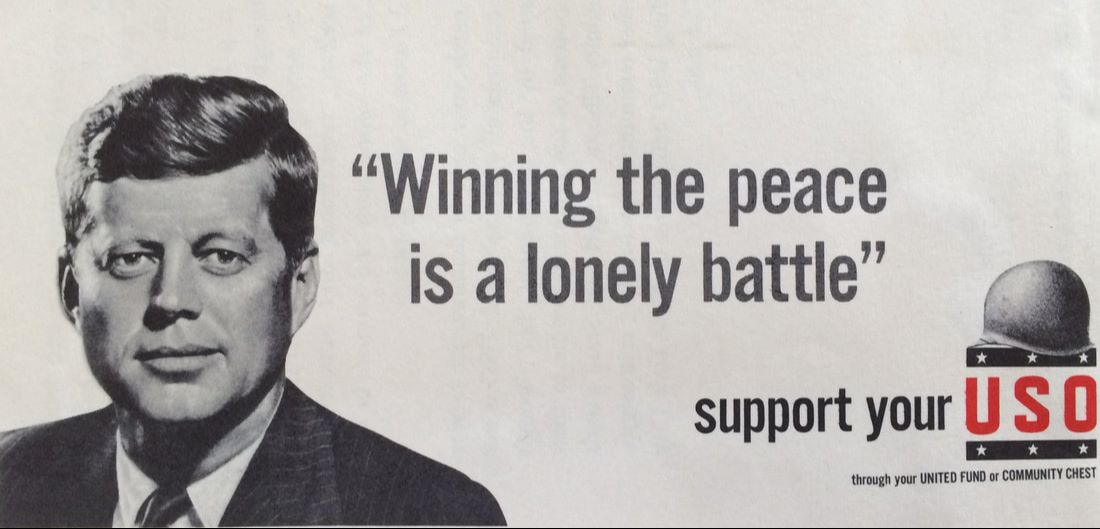

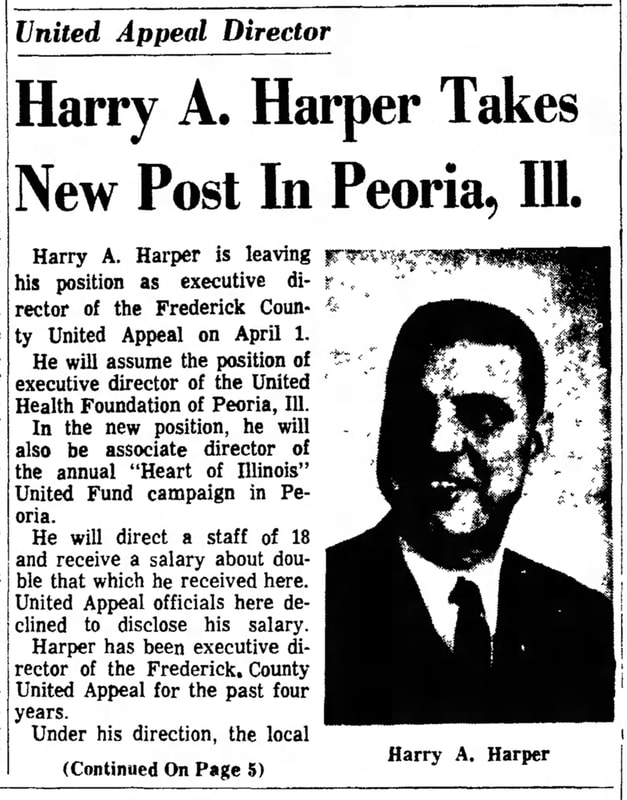

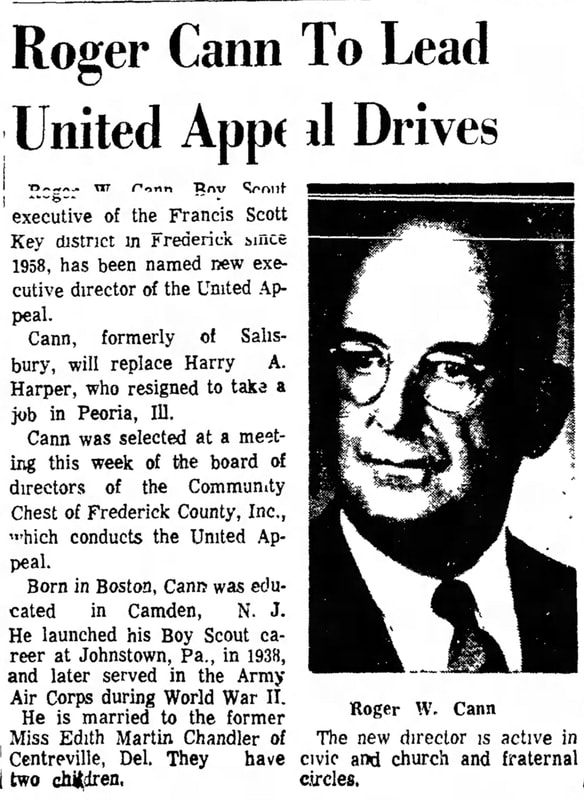

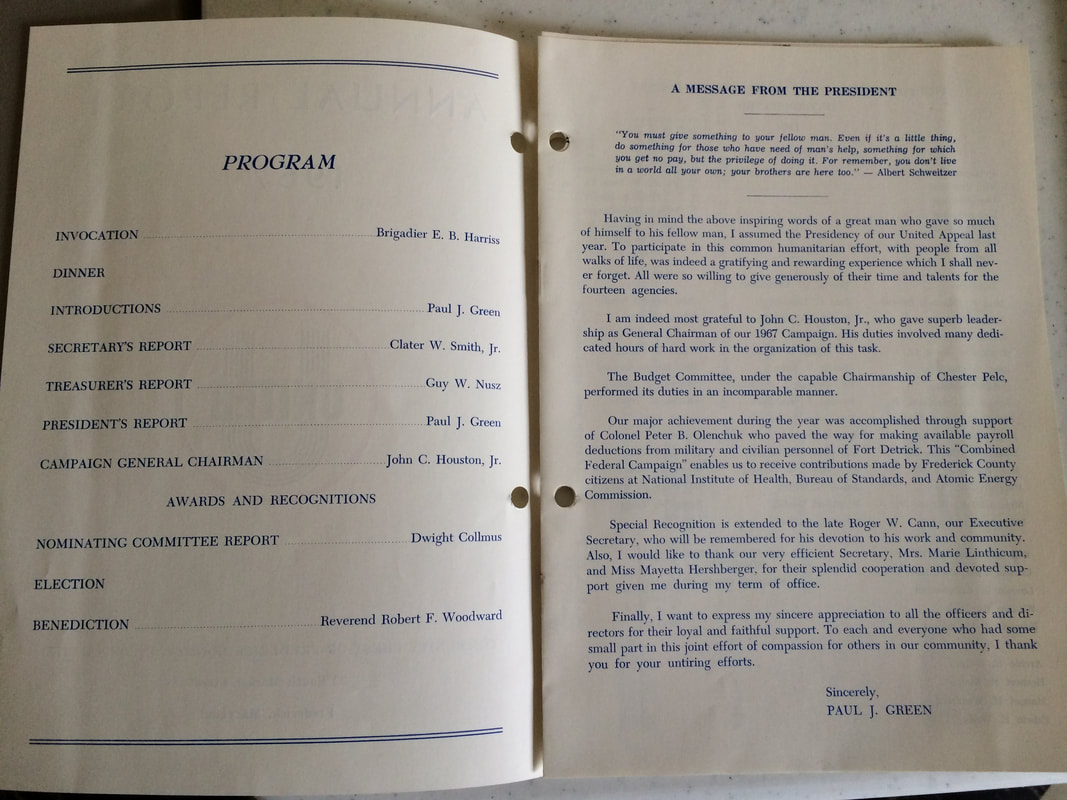

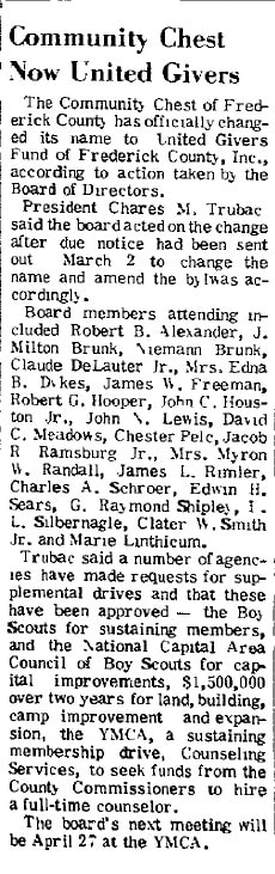

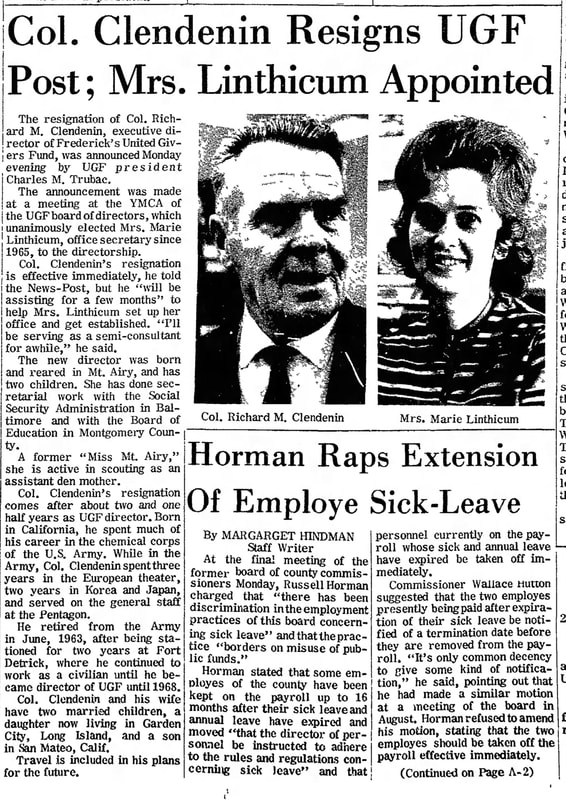

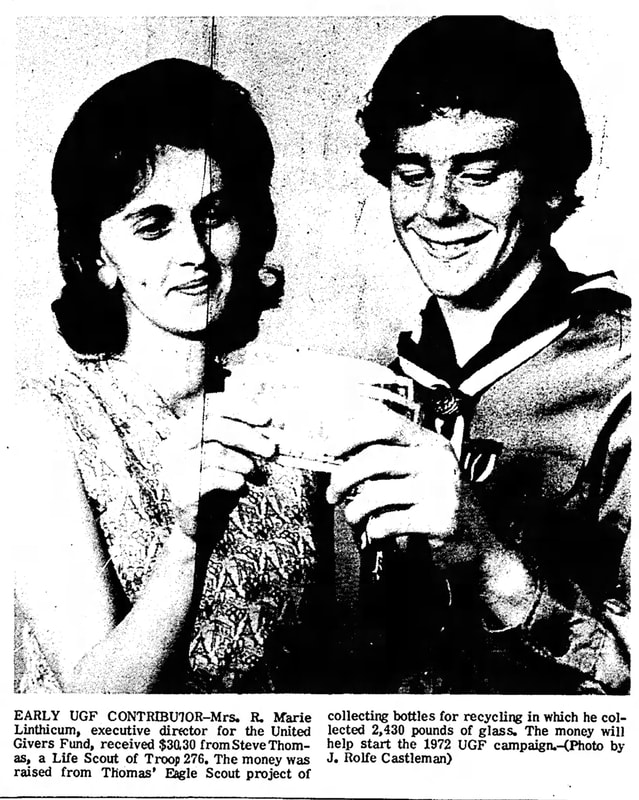

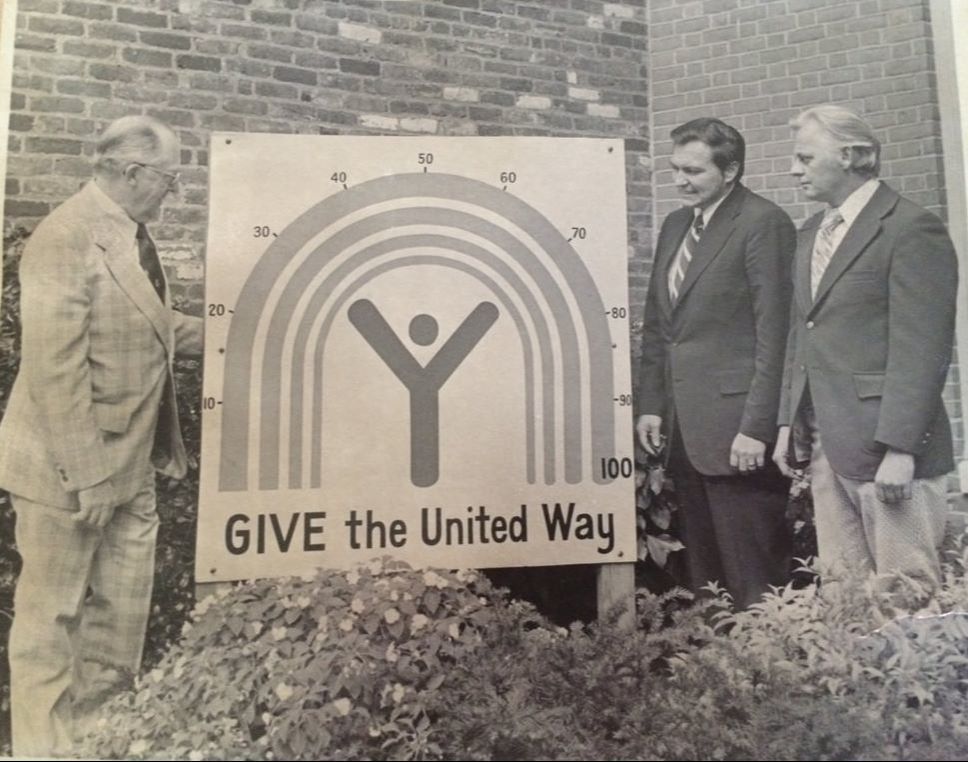

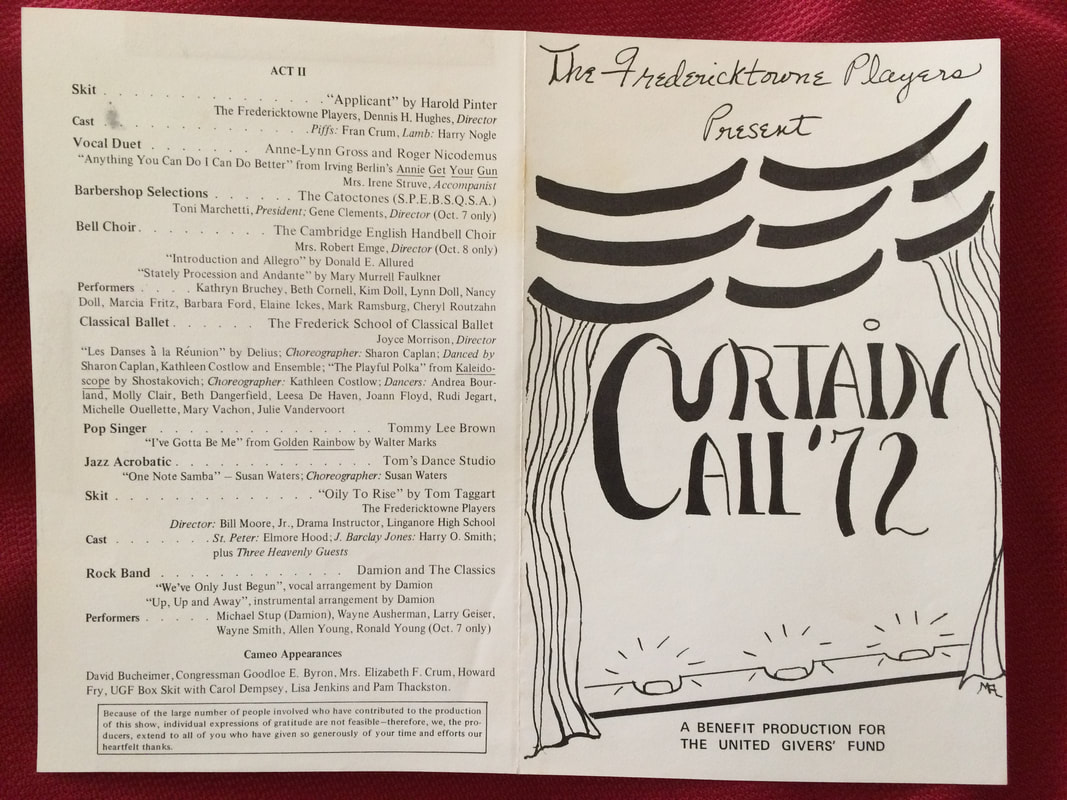

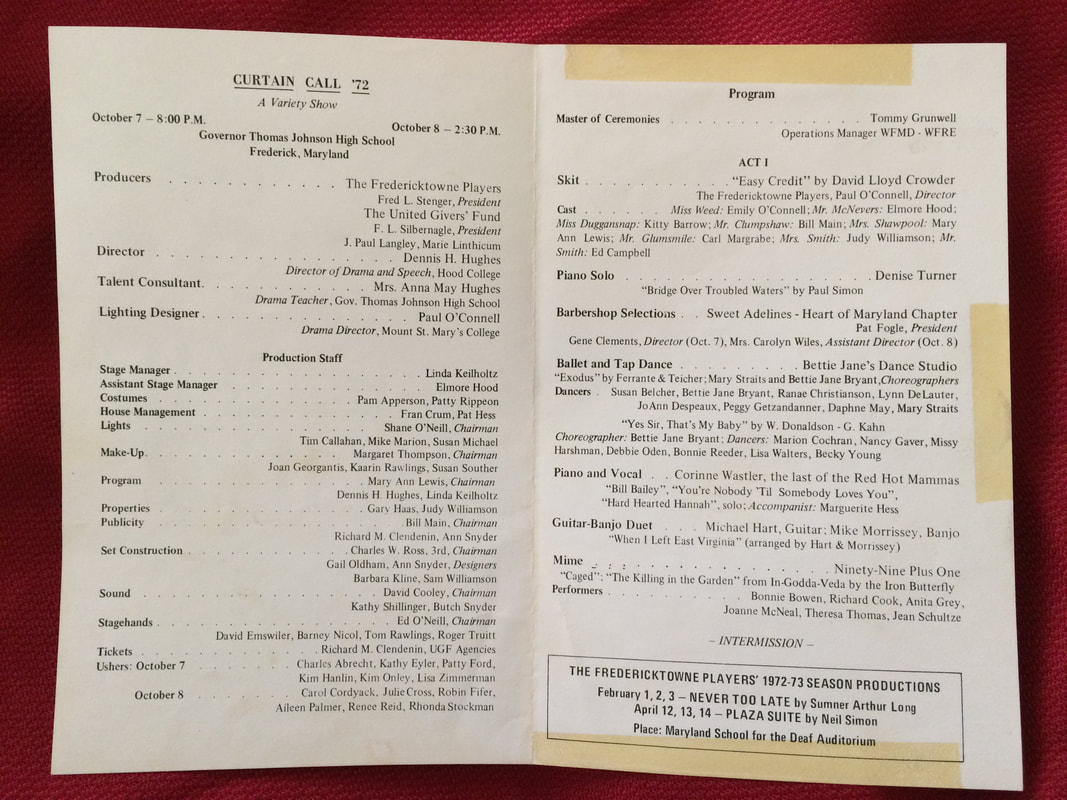

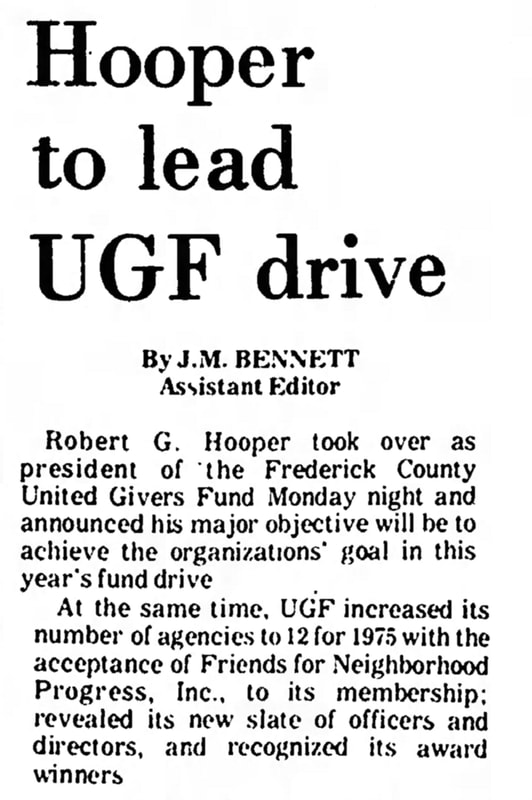

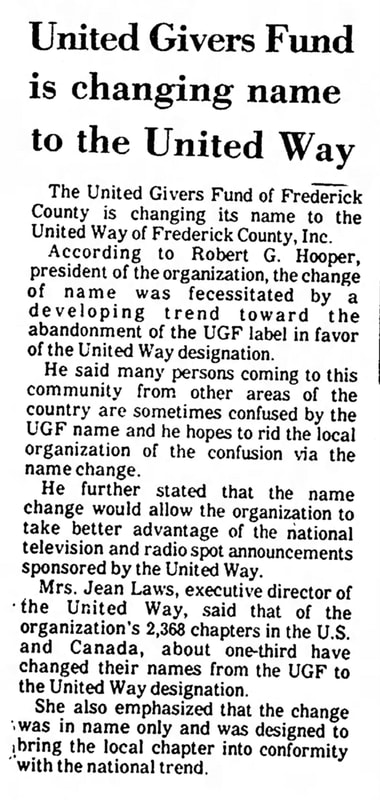

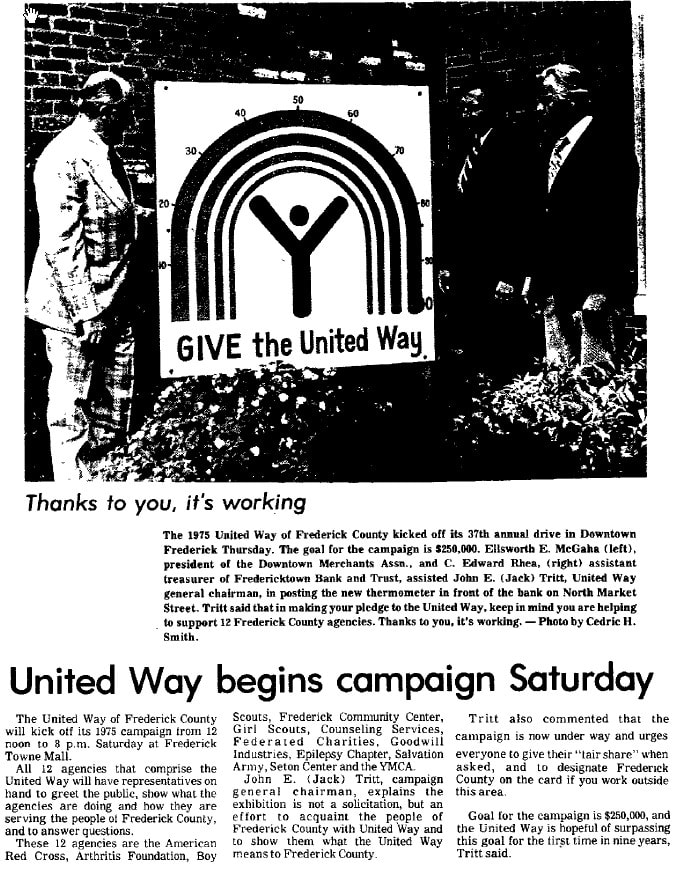

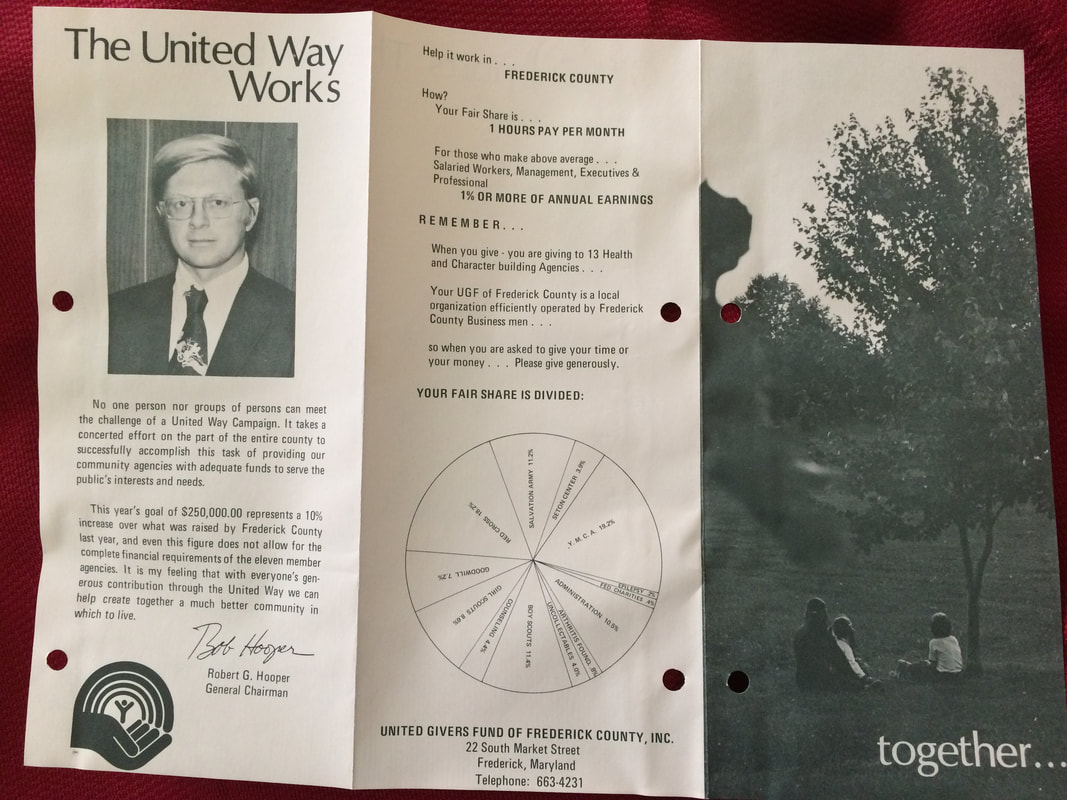

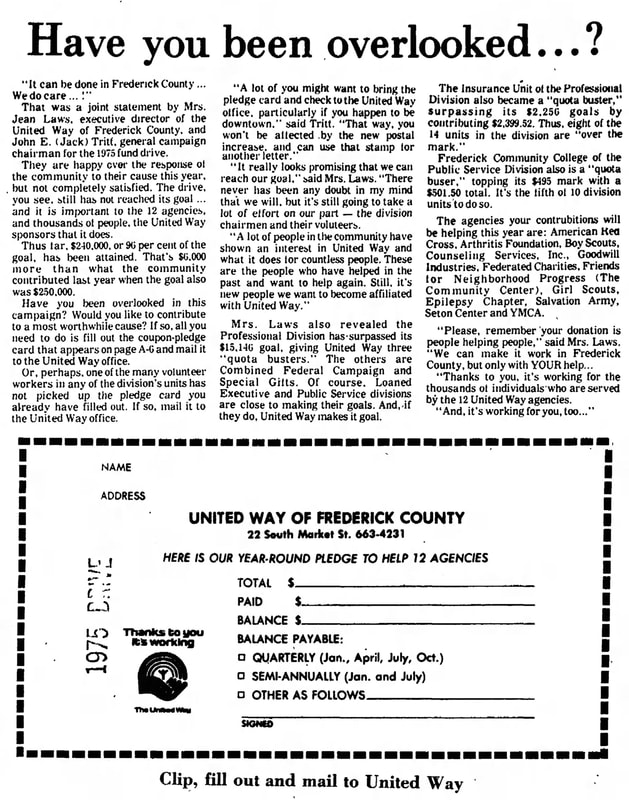

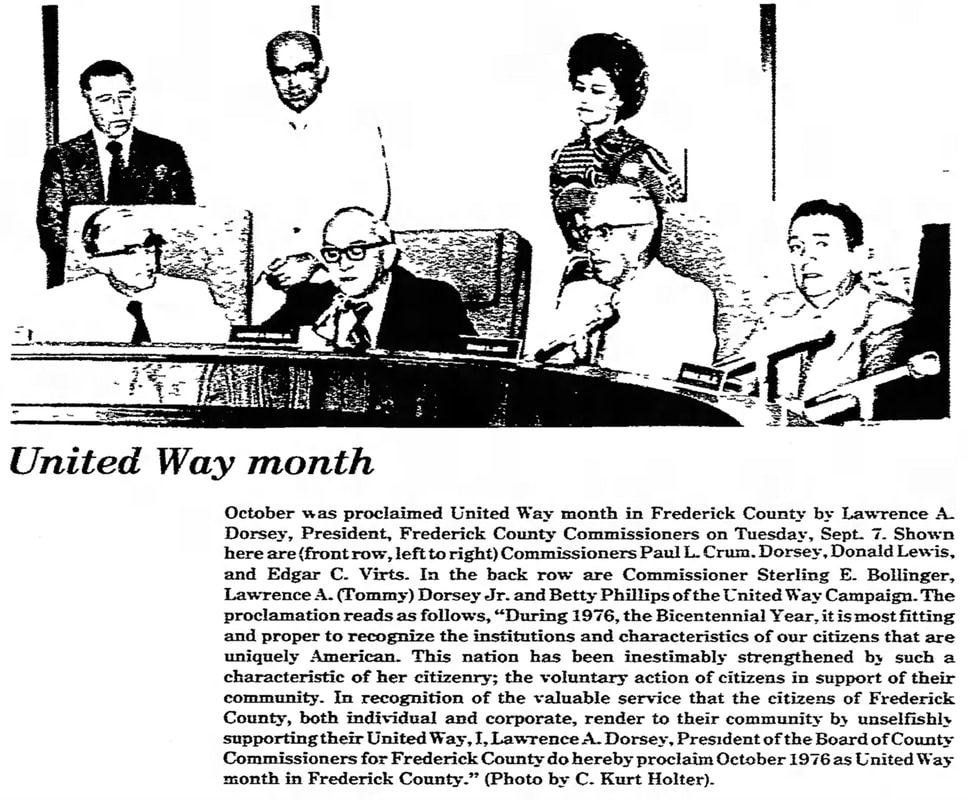

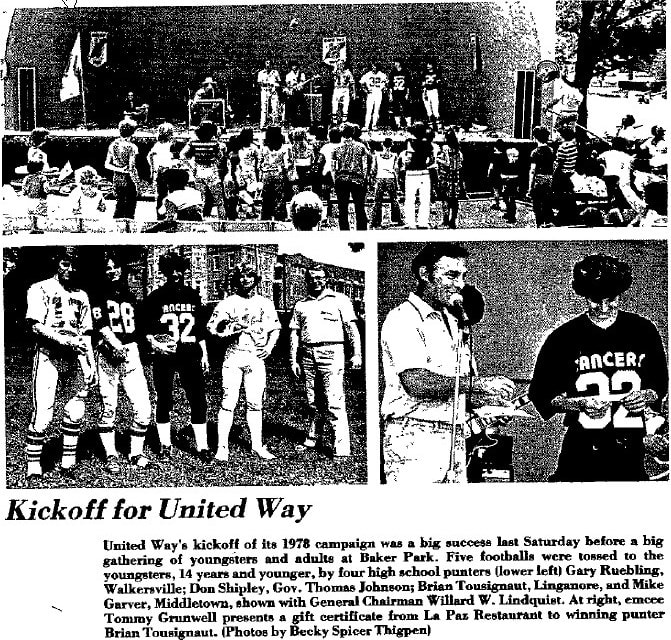

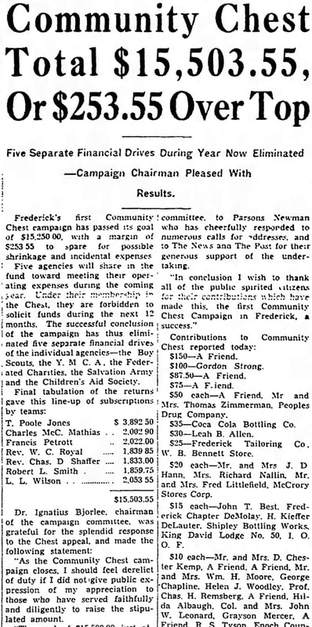

"In an impassioned speech to both houses of Congress on May 25th, 1961, US President John F. Kennedy announced his ambitious aim of sending an American to walk on the moon before the end of the decade. Calling for a massive injection of extra funds into the space program, the President said: "I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to Earth." The President went on to say that an estimated $9 billion would be needed over five years for research and development of the technology that would be required to make lunar exploration a reality, but that he did not envision the need for new taxes to raise the funds. In truth, Kennedy’s announcement was motivated by a number of political factors. He had been blamed for the failed Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba by anti-Castro exiles in April, and had also seen the Soviet Union beat the US into space when Yuri Gagarin made his orbit of the Earth that same month. There was also a genuine fear of allowing the Soviets to get too far ahead in the Space Race in terms of what it might mean for their strategic power. “We go into space because whatever mankind must undertake, free men must fully share,” said the President. Frederick County got caught up in "space exploration fever" as well, trickling down to the Community Chest Appeal of 1961. "Appeal rockets" now took the place of the formerly used "appeal thermometers." The "Rocket" on its launching pad was designed by Larry Hauver, an 11th grader at Thurmont High School. Seven of these were placed at various locations around the county: Downtown Frederick, the Frederick Shopping Center at 7th Street, Fort Detrick, Walkersville, Thurmont and Middletown. Executive Director Willard H. Markey was soon replaced by Sgt. Harry A. Harper. Ironically, or by design, the air & space motif was kept intact as Sgt.Harper was a former Air Force recruiter in Frederick who retired from the military in 1961. Harper would serve the Frederick Community Chest over the next four years until 1966. Of particular note during Mr. Harper’s tenure was the October 1963 Kickoff Meeting for the United Fund’s 1963 fall campaign. Mr. Harper described the rally held in West Frederick Junior High School as “one of the most enthusiastic rallies ever to be held in the area”. The principle feature of the event was a collection of short reports given by the 11 member agencies of the United Appeal.  Robert F. Kennedy Robert F. Kennedy The overall worldwide economic trend in the 1960s had been one of prosperity, expansion of the middle class, and the proliferation of new domestic technology. Rapid social and technological changes brought about a growing corporatization of America and the decline of smaller businesses, which often suffered from high post-war inflation and mounting operating costs. Local employers were urged to utilize the payroll deduction method of securing pledges by their employees for contributions. Encouragement came from the nation’s capital as telegrams were received from Frederick native and US Congressman Edward McCurdy “Mac” Mathias, Jr., and another from US Attorney General, Robert F. Kennedy, brother of the president of the United States. Both messages were addressed to the Chest's General Campaign Chairman, John W. Morgan. Kennedy’s telegram read: “Congratulations to you and all your volunteers joining with you in your “kick-off” of the 1963 campaign. Your joint efforts are in the finest American tradition of people helping people. I am congratulating you and wishing you well (signed) Robert F. Kennedy.”  Turbulent Times Robert F. Kennedy’s brother would be assassinated just a month later in Dallas, Texas. The Kennedy family had captured the imagination of the country, especially young people. In response to civil disobedience campaigns from groups like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), President John F. Kennedy, pushed for social reforms. His death was a shock to the nation. The reforms of former President Kennedy were finally passed under Lyndon B. Johnson including civil rights for African Americans, and healthcare for the elderly and the poor. The confrontation between the US and the Soviet Union dominated geopolitics during the 1960s, with the struggle expanding into developing nations in Latin America, Africa, and Asia as the Soviet Union moved from being a regional to a truly global superpower and began vying for influence in the developing world. After President Kennedy's assassination, direct tensions between the US and Soviet Union cooled. However, the heavy-handed American role in the Vietnam War outraged student protestors around the globe. With escalation of this war throughout the second half of the decade and into the next, the Red Cross took on an air of greater importance for charity at home. New member agencies to the Community Chest over the previous few years were Travelers Aid, (1963), Kids Incorporated (1963), Epilepsy Chapter (1965), and Fort Detrick Youth Activities (1965). In 1966, new resident Roger Cann was appointed to succeed Harry A. Harper, who had left the area after being lured away to become executive director of the United Health Foundation in Peoria, Ill. Cann, a Boston native had come to Frederick by way of Salisbury, Maryland. During Harper’s four years at the helm, Frederick’s United Appeal rose from a nine-agency drive raising $120,000 (and not meeting its goal year after year) to a 13-agency drive which raised $161,000 in Harper’s last year (1965) exceeding its goal for the second straight year. Cann had great familiarity with the United Appeal and Community Chest because he had served as District Scout Executive for the Francis Scott Key Boy Scouts since 1958.  Sadly, Roger Cann’s tenure would be cut short by his sudden death in early January of 1968. The Community Chest Board found their new leader in retired Army colonel Richard Clendenin, who resigned his position as Public Relations Officer for Fort Detrick to serve as Executive Director of the annual United Fund campaign. Clendenin was part of the Army’s Chemical Corps and at one time served on the Pentagon’s general staff. He had been assigned to Fort Detrick, where he stayed until his retirement from the Army in 1963. His talent as an amateur actor and director endeared him to the local community as a regular with the Fredericktowne Players theatrical group.  The Fall campaign of 1967 marked the 30th such drive in the organization's existence. That first-ever Chest campaign of May, 1938 achieved a collection of $15,503.55. At the Community Chest's "Annual Appeal Recognition Dinner" held in February 1968, Chest President Paul J. Green remembered the late Roger W. Cann "for his devotion to his work and community." He also thanked his campaign chair John C. Houston on raising $160,916 thus achieving 93% of the appeal goal of $172,127. Last, but certainly not least, two special ladies, Mrs. Marie Linthicum (Community Chest Secretary) and Miss Mayetta Hershberger, (volunteer extraordinaire) were praised by Green for their "splendid cooperation and devoted support" during his term in office. The Community Chest of Frederick County closed out the decade with presidents Francis W. Bush Sr. in 1968 and James L. Rimler in 1969. The 1968 campaign raised $171,391 out of a goal of $190,000. To end the decade, the Chest "shot for the stars" with a campaign goal of $200,000. Although the goal was not achieved, the Community Chest of Frederick County would raise $183,840 for its partner agencies.  Recounting the fashion trends of the period is an exercise not for the squeamish Recounting the fashion trends of the period is an exercise not for the squeamish Super Seventies Historians have increasingly portrayed the 1970s as a "pivot of change" in world history focusing especially on the economic upheavals, following the end of the postwar economic boom. Social progressive values that began in the 1960s, such as increasing political awareness and economic liberty of women, continued to grow. Most industrialized countries experienced an economic recession due to an oil crisis caused by embargoes. The crisis was felt by consumers and featured such travesties as skyrocketing mortgage rates and long lines at gas pumps. Novelist Tom Wolfe coined the term “the ‘Me’ decade" in an article published for the New Yorker Magazine. The term described a general new attitude of Americans towards atomized individualism and away from communitarianism, in clear contrast with the 1960s. It was a time that saw people embrace entertainment and consumer culture like never before. These factors seemingly would stack the deck against federated giving. In 1970, a name change came to the organization originally founded in 1938 as the Frederick Community Chest. The new moniker given was the United Givers Fund of Frederick County, Inc. In addition to a new name, Goodwill Industries became the group’s 14th member agency at this time. In late December, 1970, Col. Clendenin would announce his resignation in order to enjoy retirement and devote more time to his acting hobby. A surprise move was on the horizon in the form of Clendenin’s replacement—one that seems so fitting with the rise of the second phase of the feminism/women’s movement. This period was ripe with activity aimed to gain greater equality for women by giving more than just voting rights, as it included domestic issues (such as clothing and a break with traditional household roles) and employment. At a meeting of the Frederick County United Givers Fund (UGF) Board of Directors in late November 1971, an announcement was made that the Board had unanimously elected Mrs. Marie Linthicum as executive director. The Mount Airy native (and mother of two) had served as office secretary since taking over from Helen Croghan in 1965. Linthicum’s previous work experience included secretarial duties held with the Social Security Administration in Baltimore and the Board of Education of Montgomery County. Interestingly, a newspaper account announcing her appointment states: "in addition to being active in scouting and serving as an assistant den mother, Marie Linthicum was a former “Miss Mount Airy.”  Suburbanization caused the gradual movement of working-class people and jobs out of the inner cities as shopping centers displaced the traditional downtown stores. In time, this would have disastrous effects on urban areas. In the meantime, the suburban housing market was booming. This was happening here in Frederick. City residents and newcomers moved into the suburbs of Frederick. Developments such as Clover Hill, Frederick Town Village, Eastgate, and townhouse communities such as Amber Meadows and Waverly Gardens offered safehavens away from the declining downtown area. Downtown businesses were following suit, or receiving newfound competition from the many restaurants and stores that would open within two major shopping malls, built during the decade. Surrounding corridors including The Golden Mile (US40) and Evergreen Point (MD85) would become commercial meccas. UGF, We hardly Knew You The United Givers Fund of Frederick County of the early 1970s would be led by the likes of Charles M. Trubac, Vice-President of State Farm Insurance (1970); James W. Freeman, President, Frederick Gas Company (1971); F. Lawrence Silbernagel, Regional VP of Maryland National Bank (1972); Charles A. Simms, General Accounting Supervisor for Eastalco Aluminum Company (1973); and J. Paul Langley, Asst. General Manager of Capitol Milk Producers (1974). In 1972, Marie Linthicum was replaced by another female executive–Dorothy Jean Laws. Mrs. Laws was no stranger to the organization, having served as Executive Secretary for the United Giving Fund of Wicomico County since 1962. She was exactly what Frederick County needed, and would prove invaluable as yet another outsider who brought fresh ideas and perspective to the community. Laws' previous experience with United Giving campaigns was paramount. This would be an era where a stronger relationship would be built between the local chapter and the parent organization, United Way of America, which had recently moved its headquarters from New York City to nearby Alexandria, VA in 1971.  QB Roger Staubach for the United Way QB Roger Staubach for the United Way One of the top achievements of Frederick’s newly named UGF organization in the early 1970s was heightened visibility outside the traditional campaign model. This came with successful sponsoring of unique community benefit events. The entity would begin hosting annual golf tournaments, a "Show & Tell" exhibit at the newly constructed Frederick Towne Mall, and variety talent shows. Entitled "Curtain Call '72," the UGF's first variety show was held at Gov. Thomas Johnson High School's auditorium on October 5th, 6th and 7th, 1972. The Fredericktowne Players were of key importance in making this opportunity a reality, as was former UGF Executive Director Richard Clendenin who aided the production in several ways. A second show was held in 1973 with help from the Frederick Jaycees. The 1970s would also be a period in which cooperative marketing and advertising would be introduced in earnest. Here locally, cartoon-style advertisements began appearing in the Frederick News-Post with more sophisticated advertising would follow. In 1973, the national United Way took an unlikely partner in increasing public awareness of social service issues facing the country. This was the National Football League (NFL). In addition to public service announcements featuring volunteer players, coaches and owners, NFL players began supporting their local United Ways through personal appearances, special programs, and participation on United Way governing boards. In 1974, United Way and the NFL undertook the largest public-service campaign in the nation’s history. The televised commercial spots called “Great Moments” were a major key in bringing greater awareness. United Ways would raise $1.68 billion, a 10.1% increase over the previous year. The campaign worked, and continues to this day. In Frederick County, Executive Director Laws helped in raising $233,489 with leadership from President J. Paul Langley and Campaign Chair Robert G. Hooper (Branch Mgr. Baker, Watts & Co.). Hooper was a legacy member of the organization, as his father, J. Harold Hooper, had served as Frederick Community Chest president in 1959. Bob Hooper would take the reins of the UGF the following year as president in a year which a 12th agency member was added—Friends for Neighborhood Progress. In April 1975, it was announced that the United Givers Fund of Frederick County name was going to be changed to the United Way of Frederick County. According to President Hooper, the name change was necessitated by a developing trend toward the abandonment of the United Giving Fund label in favor of the United Way designation. He said that many persons coming here from other parts of the country were confused by the UGF name. This was also a testament to the nationwide exposure that heightened advertising was providing. A Flood of Leadership Another community leader who gave of his time and talent to lead the organization through the mid 1970s was John E. “Jack” Tritt. Tritt was purchasing agent for Frederick County Schools. As president during the nation’s Bicentennial Celebration year (1976), he was also in the lead during a special time in Frederick's history as Frederick had been named an All-America City by the National Municipal League. This award came thanks in part to activism shown by civic participation and problem solving by the United Way and its predecessors (UGF/Community Chest) and a group called Operation Town Action, a group focused on rebuilding the struggling downtown. The latter was led by residents Don Linton and Peggy Pilgrim and Curtis Bowen. Jack Tritt was aided by a true legal team of campaign chairs: Lawrence A. “Tommy” Dorsey, Jr., a local attorney whose father was sitting president of the Frederick County Commissioners; and G. Edward Dwyer, another practicing lawyer who later would earn distinction as a chief judge of the 6th Judicial Circuit (serving from 1991-2016). In mid-September, a photo appearing in the Frederick News showed Campaign Chair Dorsey receiving a ceremonial citation from the Frederick County Commissioners, presented by his father, declaring the upcoming month of October as “United Way Month.” A goal of $272,000 had been set.  Frederick Post (Oct 7, 1976) Frederick Post (Oct 7, 1976) Unfortunately, the spotlight wouldn’t stay on the organization long as tragedy would strike weeks later on October 5th, 1976. A devastating flood did nearly $25 million dollars in damage to downtown Frederick, and several other sites around Frederick County as the effects were felt of an abnormal storm producing abundant rains. It was a trying campaign as can be imagined. Frederick, and the local United Way chapter, received a wake-up call with the flooding. It had never experienced catastrophes such as hurricanes, tornadoes or earthquakes like other towns and cities. This was a major disaster, and the community came together to help, rebuild and plan for the future.  Bentz and W. Church streets during the Great Frederick Flood of 1976 Bentz and W. Church streets during the Great Frederick Flood of 1976 The Great Frederick Flood of ‘76 was a major point of change in local history. The United Way contributed to the relief efforts. Help was especially exemplified through one of its partner agencies—the Red Cross of Frederick County. In 1976, the organization would receive $22,709 in funds from the United Way of Frederick County. Perhaps fate, but more so, the experience of the previous year, led to over $265,000 in campaign collection to hit a 97% success rate with the campaign. The following year would achieve 100%. It had taken Executive Director Jean Laws five years, but she had got the campaign to meet its quota, the first time in 11 years since it was achieved in 1965 under President Dwight Collmus and Campaign Chair Charlie Main. At a recognition dinner in February 1977, incoming UWFC President Tommy Dorsey had the distinct pleasure of presenting Patricia G. Sykes the award for Outstanding United Way Volunteer of the year. Ms. Sykes, a Texas native, directed the United Way’s publicity campaign, which featured numerous, well-written articles on the organization’s 12 partner agencies, and volunteer chairmen. Sykes was the first woman to ever receive the award, and received a standing ovation from the capacity crowd assembled at the VFW Country Club. President Dorsey called Ms. Sykes “the epitome of caring.” In April, 1977, the UWFC welcomed another partner to the fold—Frederick County Association of Retarded Citizens. Big Brothers and Big Sisters had recently come on board as well, bringing the total of member agencies to 14. The desired set goal of $284,000 was attained during the ’77 campaign. Dorsey confidently handed the presidential gavel to G. Edward Dwyer the following year—not to mention the fact that Dwyer was also given a desired campaign increase for the organization’s 40th anniversary year. Two more non-profits would join as partner agencies—Mental Health Association and the Learning Tree, Inc. The 40th annual campaign kickoff event held on September 9th, 1978 was just that. The commemorative event featured interesting football-related novelty events such as having five local, high school kickers on hand to actually “kick-off” the event. Local radio “on-air” personality Tommy Grunwell hosted the event at the Baker Park Bandshell. All in all, it was a great way to connect the local chapter to the national advertising campaigns involving the partnership with the NFL. Meanwhile, Judge Ed Dwyer, as he is best known today, together with his campaign chair, Willard W. Lindquist along with the United Way of Frederick County's campaign team, bested their 1978 goal of $324,000 by “scoring” a definite touchdown with an extra point in a 101% effort garnering a final tally of $328,500.  The United Way family now included: the American Red Cross, Arthritis Foundation, Big Brothers-Big Sisters, Boy Scouts of America, Counseling Services of Frederick, Epilepsy Chapter, Girl Scouts of America, Federated Charities of Frederick County, Frederick Community Center, Frederick County Association of the Retarded (later known as ARC), Goodwill Industries, Learning Tree, Inc., Salvation Army, Seton Center, Mental Health Association and the YMCA. Forty years of history were now officially in the books going back to the day of incorporation as the Community Chest, April 11th, 1938. As the organization was under its third moniker, the United Way of Frederick County, Inc. had shown that it was still growing as a perennial winner for Frederick and Frederick County. As a sign of the times, one could say that they were caught up in "Saturday Night Fever" doing much more than simply "Stayin' Alive." This of course is a nod to super-group the Bee Gees who dominated the charts during the anniversary year.

3 Comments

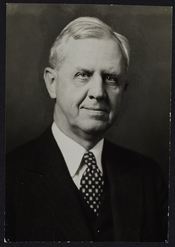

1938-1958 A fortunate occurrence in local history occurred in the year 1938. It was the beginning of “united giving” in Frederick with the formation of the Community Chest. This fund-raising organization was created to collect money from local businesses and workers to be distributed toward important charity and philanthropic projects in the community. The initial impetus of the program came as a remedy to assist in funding the operating budgets and capital needs of several partner agencies.  Joseph D. Baker "Frederick's First Citizen" Joseph D. Baker "Frederick's First Citizen" “Timing is everything” as they say. Ironically, or by divine design, this was the same year that Frederick lost its great and iconic benefactor—Joseph D. Baker. Given the moniker of “Frederick’s First Citizen,” Mr. Baker died October 6th, 1938 at the age of 84. His legacy includes generous donations that would create the Buckingham School for Boys; the Record Street Home for the Aged; the Baker Annex at Frederick City Hospital for the county’s African-American population; the Frederick YMCA; a new home for Calvary Methodist Church and a spacious municipal park that bears Mr. Baker’s name. Upon his death, friend James H. Gambrill, Jr. remarked, “The influence of his life will remain as a continued benediction upon the city of Frederick.”

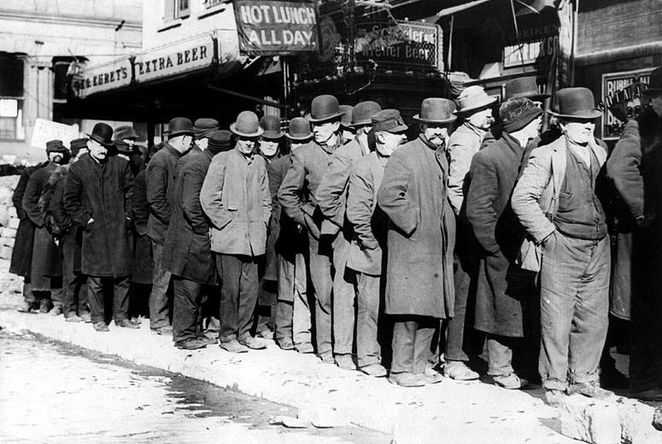

Also stepping up in times of need were local businesses such as the Frederick News, Ox-Fibre Brush Company and the Union Knitting Mills. Nothing illustrates this latter point better than the thrilling events of July 1864 during the American Civil War when Frederick’s leading banks provided necessary funds to pay the infamous $200,000 ransom levied by Confederate General Jubal A. Early. The city was spared.  The timing of Frederick’s Community Chest creation was impeccable. Over the next several decades, this organization would incur multiple name changes and eventually come known as United Way of Frederick County. All the while, the citizenry’s passionate spirit of giving has remained the same for 80 years. Earlier Frederick residents and business persons have passed the torch to later generations, as well as newcomers to the area, dedicated to the cause of assisting the unfortunate and impoverished in our community. For eight decades, a variety of non-profit groups and agencies have received invaluable support from Frederick’s “united giving” organization thanks to both big and small business entities, local institutions and private citizens. Donations have come in the form of manpower hours, cash pledges, matching grants and supplies totaling in the tens of millions. Today, United Way of Frederick County brings the community together to provide resources that aid people in need, or at risk, in order to help solve problems. This is the same intention that started the organization here in 1938.  GENESIS (1938-1958) Although we look to 1938 as the year of founding, United Way of Frederick County was first conceptualized nearly a century ago, thanks to the mobilization of the country’s population and economy during World War I. The support efforts on the home front required soldiers, food, ammunition and money—key necessities to win the international conflict. Frederick County residents certainly did their part, and Allied efforts secured victory in November, 1918. All the while, valuable lessons regarding the importance of preparedness and teamwork were gleaned from this terrible chapter in our country’s history. As soldiers returned home from Europe and elsewhere, the United States found itself as one of the world’s top military and economic powers. National leaders saw the need for better organization and improved amenities at home. Soon began infrastructure changes to the armed forces, roadways and transportation systems, and government agencies. It was a time of social and political reform, and economic prosperity that would usher in “the Roaring Twenties.” At the local level, community leaders, residents and veterans alike could reflect upon the power of their collective actions in the recent war effort. Many began to feel a renewed vigor, and entertained the notion of waging war on a new foe—the ills and social problems here at home. These could be addressed by a “united” effort of care and fund-raising among neighbors, in an attempt to further improve Frederick County.

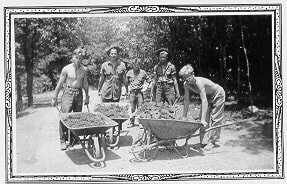

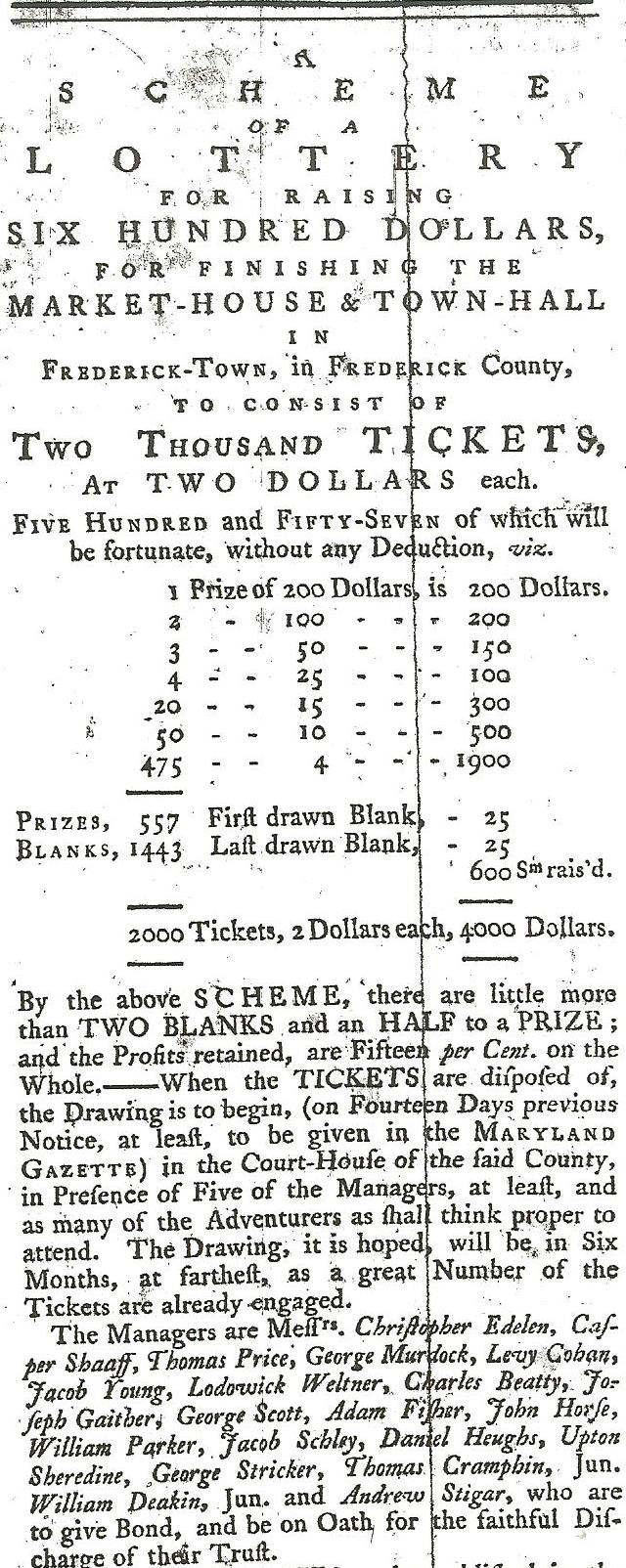

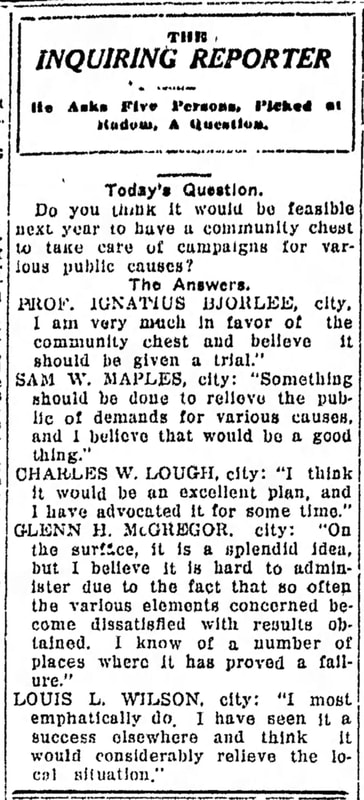

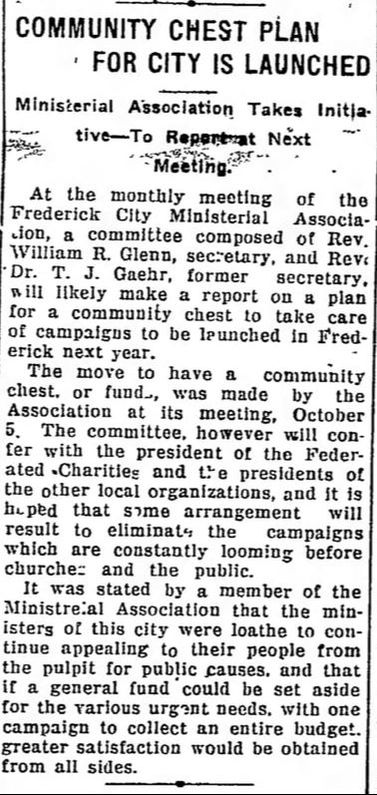

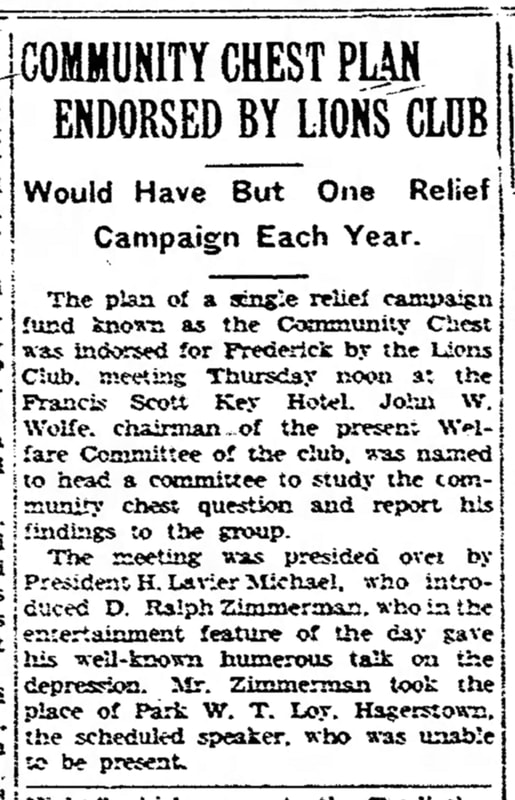

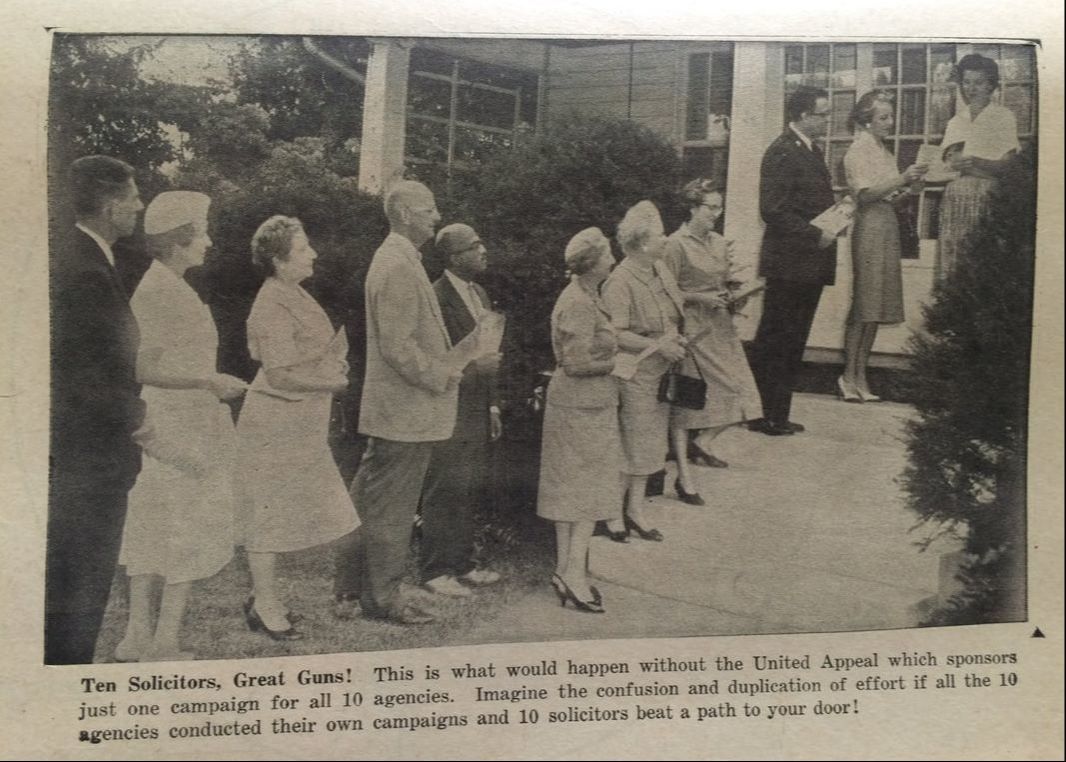

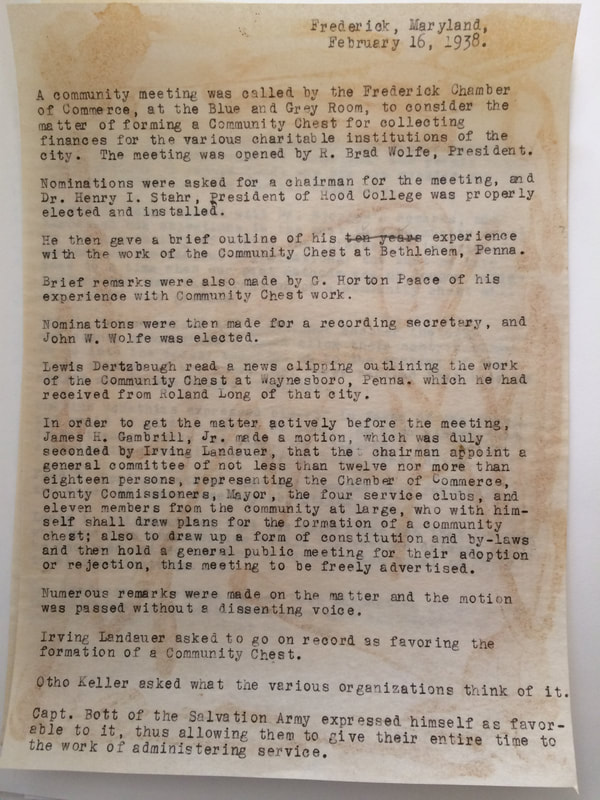

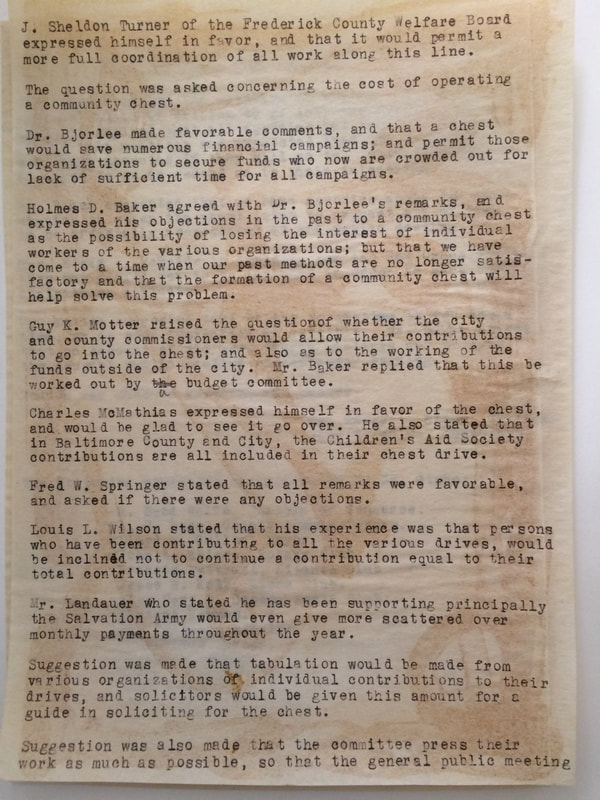

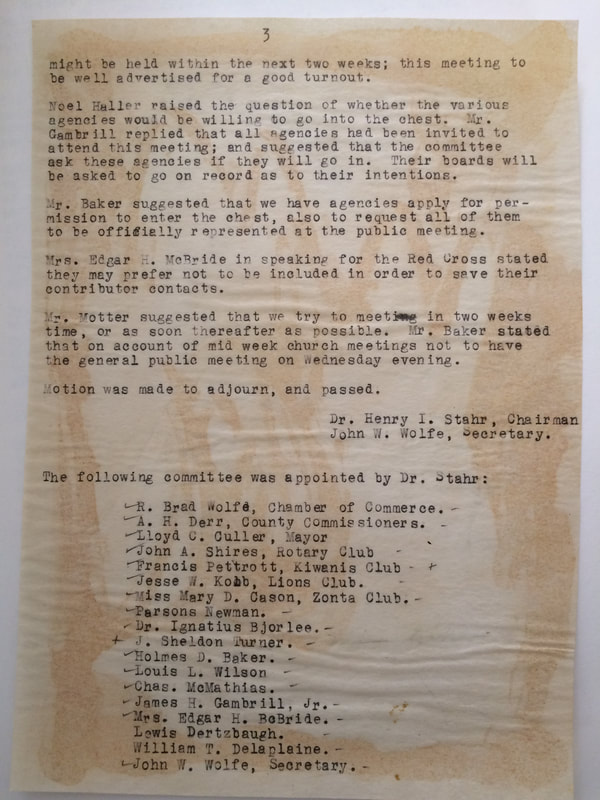

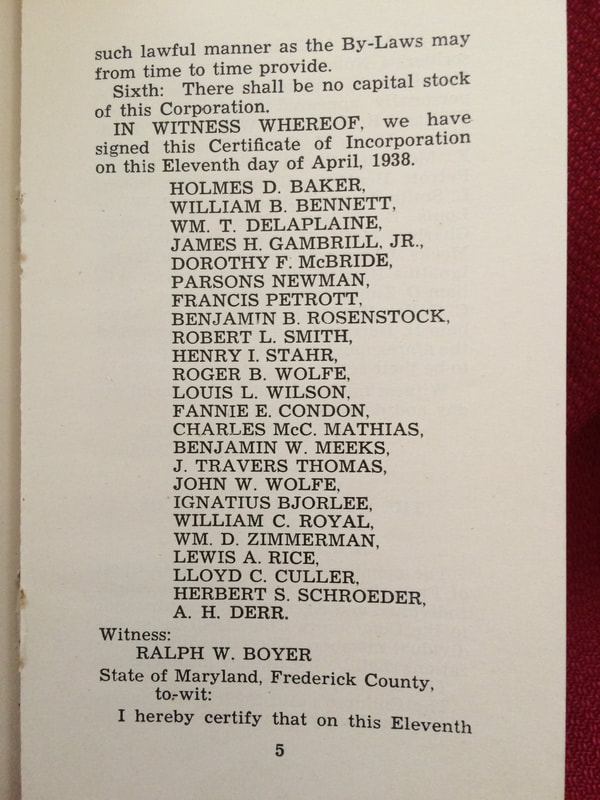

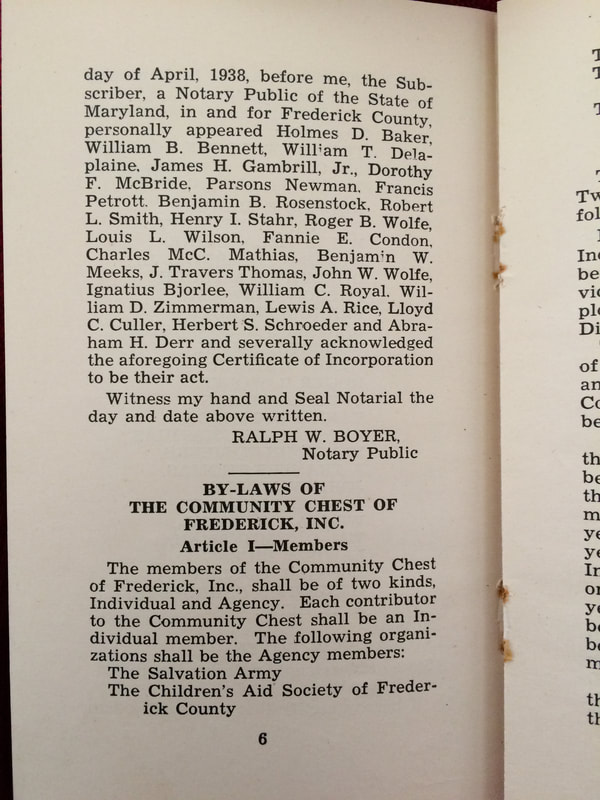

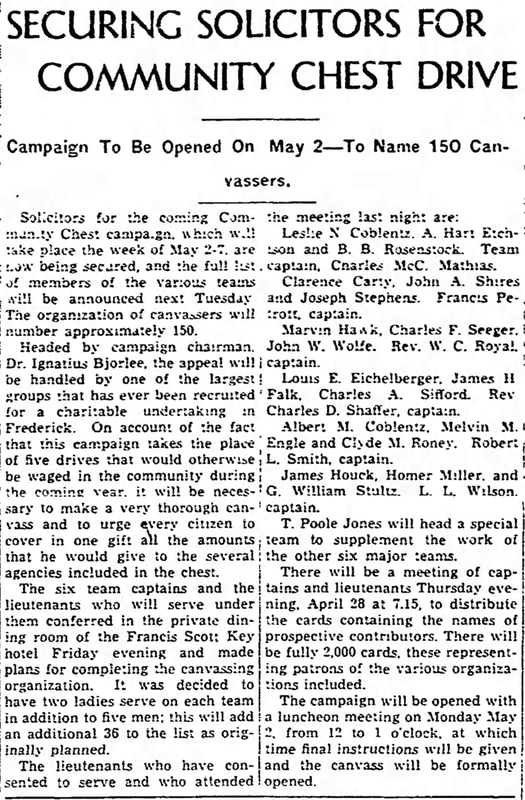

The Community Chest organization dates back to Cleveland, Ohio and the year 1913. It had the purpose of conducting organized, fundraising campaigns with local businesses and employees—the proceeds distributed to important local projects. The drive to establish a group like this in Frederick would take several years as not everyone favored the idea. Consternation and cynicism were expressed by more than a few of Frederick’s established fundraising enclaves such as fraternal organizations, church councils and civic groups. Some felt that a new “charitable union” would undo individual successes, and feared fund management by someone other than themselves. The matter of a united fundraising entity would be tabled until 1932, at which time the Frederick Lions Club re-introduced the idea for a Community Chest program. John W. Wolfe, chairman of the Lions’ Welfare Committee, was named to head a group to study the "Community Chest" concept and report his findings to the club. A year later, the local chapter of the Salvation Army would endorse a community chest for Frederick at its June meeting in 1933. Again, no formal movement would be taken. Florence Garner, leading member of the Federated Charities organization was among the Salvation Army’s advisory board in support of the plan. Founded in 1911, Federated Charities was headquartered at 22 S. Market Street in the old home bequeathed by Margaret Janet Williams, daughter of a former Frederick banker, John H. Williams. This umbrella group oversaw a Free Kindergarten for the community and the operation of the Charity Organization Society which provided assistance to families that could not be helped by other agencies. Services included a Prenatal Care Clinic, visiting nurse and drug prescriptions and the distribution of medical equipment, food, heating oil and used clothing to families that qualified. Florence Garner was the General Secretary of Federated Charities and carried a great deal of clout in the community, especially in addressing medical and social needs. She had originally come to Frederick from Ohio in 1912 to fill the organization’s position as visiting nurse. Ms. Garner helped lay the initial groundwork for Federated Charities and rose to lead the organization, staying for 38 years until her retirement in 1950. Having Ms. Garner as an advocate (for a Frederick Community Chest) certainly spoke volumes.  Certificate of Organization Membership for the Frederick County Chamber of Commerce Certificate of Organization Membership for the Frederick County Chamber of Commerce Enter the Chamber The country was quite a bit different than it had been a decade earlier. Residents had seen the legendary stock market crash of 1929, launching the era known as the Great Depression. Its effects would be felt for over 12 years as many people lost money in the form of savings and inheritances. Others found themselves without jobs, with new ones hard to find. In 1930, more than 14,400 people lived in Frederick City, the county population was 54,440. There were plenty of businesses and employers in town, but Frederick sorely lacked jobs in large industry. Regardless, Frederick had an organized Board of Trade, originally chartered in 1912. The newly christened Frederick County Chamber of Commerce was the first chartered “Chamber” in the United States. In the 1920’s, the local Chamber adopted the slogan, "If Frederick is worth living in, it is worth working for!"  CCC workers constructing the Catoctin Recreational Demonstrational Area CCC workers constructing the Catoctin Recreational Demonstrational Area Meanwhile, President Franklin D. Roosevelt was moved to institute his “New Deal” plan (1933-1938) as a means to provide employment through federal programs such as the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) among others. If there was ever a time for much needed charity, this was it. A few years would pass until January 1938. The time to consolidate Frederick’s varied charity drives was long overdue. The Frederick County Chamber of Commerce announced a goal to secure a community chest for Frederick, once and for all. Chamber members and local businesses had oft been targeted to assist in leading, and making contributions to, local charity campaigns. Oftentimes this would make many individuals and businesses feel overwhelmed by multiple requests to participate in competing fund drives. Worse yet, they found it increasingly hard to say no.  The Community Chest offered a great solution for pooling resources and time, not to mention cross-marketing the many needs of the community to the populous. Plans were discussed for a single, annual drive to replace independent, money-raising campaigns. Competition would soon be eliminated as various charities would share proportionately under the Community Chest model. A community meeting was scheduled for mid-February to consider whether the time was right for a community chest for Frederick. This would be held at the Francis Scott Key Hotel in downtown Frederick on the night of Wednesday, February 16th, 1938. The following day, the Frederick News featured the headline "Community Chest Idea Gains Impetus." Thirty-three Frederick citizens and representatives of charitable causes apparently "threshed" out the question of whether it could be carried out. Hearty sentiment was shown, and without dissent, the group voted that a committee of 19 persons draw up plans for such a chest and submit them at a public meeting to be held for the purpose within three weeks. The actual minutes from this meeting are preserved within the archives of Heritage Frederick (formerly the Historical Society of Frederick). They appear below: On March 22nd, a public meeting to consider the draft of a constitution and by-laws for the proposed Community Chest would be held at the Francis Scott Key Hotel. Here the assigned committee had opportunity to show their work. Overwhelming support was demonstrated again, and another meeting was scheduled for March 25th, one in which a board of directors would be elected and officers named. The strength and ties of the Frederick County Chamber made the “united giving” model a reality on April 11th, 1938. This was the day that the Articles of Incorporation were officially signed by 24 individuals, and filed with the State of Maryland.

Delaplaine Food Drive of 1895 Delaplaine Food Drive of 1895 The organization’s Second Vice President was William T. Delaplaine (Jr.), son of the founder of the Frederick News. Delaplaine made sure that the idea of the community chest got plenty of traction in his family's newspaper. Interestingly, his father, William T. Delaplaine (Sr.), had died as a result of contracting pneumonia attributed to tireless efforts associated with a charitable food drive performed by the newspaper during the harsh winter of 1895. The Frederick Community Chest’s secretary was John W. Wolfe, the man charged by the Frederick Lions Club to study the community chest’s feasibility a few years earlier. The first treasurer was William D. Zimmerman (Cashier of Frederick County National Bank). Also holding spots on the Board were two sons of great philanthropists from the area’s past: Holmes D. Baker (son of “Frederick’s First Citizen” Joseph D. Baker) and James H. Gambrill, Jr. (son of James H. Gambrill, successful agriculturalist and miller). The latter operated the Mountain City Mill for decades, today known more commonly as the Delaplaine Center for the Arts. Gambrill Park was named for James, Jr. in honor of his tireless fight for public recreation facilities and nature conservation. Rounding out the first Board of Directors of the Frederick Community Chest were William B. Bennett (Bennett’s clothing store), Dorothy Filler McBride (President of the Maryland State Board of Examiners of Nurses) and Dr. Ignatius Bjorlee (President of the Maryland School for the Deaf from 1918-1955). Other leading citizens to lend their support and energies included Parsons Newman (fine antiques expert), Benjamin B. Rosenstock (canning company owner), Charles McCurdy Mathias, Sr. (lawyer/politician), Russell Ames Hendrickson (owner of a ladies clothing store) and William Bartgis Storm (Citizens Bank/president of the United Fire Company).

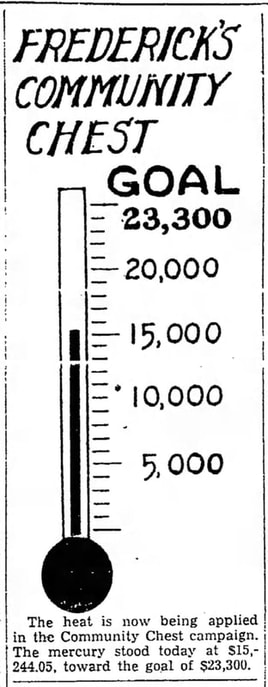

A volunteer paints in an adjustment to a Community Chest thermometer in Wisconsin A volunteer paints in an adjustment to a Community Chest thermometer in Wisconsin A “Federated” New Home By late June, 1938 the Community Chest would have a home base of operations. This would be the former domicile of Frederick banker John H. Williams. The house more recently had been inhabited by Federated Charities and was located at 22 S. Market Street. Greeting visitors was the aptly named iron, dog statue on the front portico—“Charity.” This four-legged icon had been on the site since the start of the Civil War. A second Frederick Community Chest drive would occur in May, 1939, and was headed by Robert L. Smith, District Manager for the Potomac Edison Power Company. The goal of the campaign was upped to $16,550. Results were displayed each day on a large novelty thermometer, located on the front of the Federated Charities building (22 S. Market Street). By the end of the drive period, funds were $2,500 under the goal. The family of Joseph D. Baker, Sr. stepped up with a $1,000 donation which sparked others to fulfill the goal amount. When it was all said and done, 2,359 different contributors had taken part in the campaign.

As the importance of these fundraising drives became better known to the residents of Frederick, success rates grew proportionately. The fifth Chest Drive appeal took place in May of 1942 and raised in excess of $2,000 over the desired goal. This was particularly encouraging due to a local and national climate characterized by participation in World War II causing the offshoot effects of apprehensive workers, a rising cost of living, war rationing and other unfavorable conditions. Against this backdrop, a new member was admitted to the Community Chest membership in late 1942 in the form of the Girls Scouts of Frederick. The next few years (1943-1945) would be especially trying. While war was raging on foreign soil, men and women here did their part to support the fighting troops. Many men traveled to Baltimore and Hagerstown to work in ship yards and aircraft plants. Local businesses such as the Union Knitting Mills, Ox Fibre Brush Company and the Everedy Company also played roles in the war effort.  Women packaged bandages in their homes for the Red Cross, an organization of paramount importance at this time—so much so, that the directors of the Community Chest decided to postpone their annual spring-based drive in deference to the Red Cross’ drive. When they proceeded the following fall, a partnership had been made with the National War Fund to conduct a joint campaign. This effort exceeded its quota as nearly $59,000 was garnered. The joint campaign would become the norm for the next two years. The respective campaign chairs in 1944 and 1945 were former veterans of World War I, not to mention the fact that they were from leading Frederick families: James H. Gambrill III, and R. Ames Hendrickson. After massive devastation of their own countries and loss of life, Italy surrendered in 1943, and Germany and Japan in 1945. On the other hand, the US emerged far richer and with fewer casualties comparatively. The Frederick community, and nation, learned once again the important lesson of teamwork, dedication and sacrifice in dire times of need. Post-War America Twelve million returning veterans were in need of work and in many cases could not find it. Inflation became a rather serious problem, averaging over 10% a year until 1950. Raw materials shortages dogged manufacturing industry. In addition, labor strikes rocked the nation, in some cases exacerbated by racial tensions due to African-Americans having taken jobs during the war and now being faced with irate returning veterans who demanded that they step aside. Munitions factories shut down and temporary workers returned home. Following the Republican takeover of Congress in the 1946 elections, President Harry Truman was compelled to reduce taxes and curb government interference in the economy. With this done, the stage was set for the economic boom that, with only a few minor hiccups, would last for the next 23 years. After the initial hurdles of the 1945-48 period were overcome, Americans found themselves flush with cash from wartime work due to a slowdown in buying for several years. The result was a mass consumer spending spree, with a huge demand for new homes, cars, and housewares. Increasing numbers of people enjoyed high wages, larger houses, better schools, more cars and home comforts like vacuum cleaners, washing machines—which were all made for labor-saving and to make housework easier.  Here in Frederick, many found employment at Frederick’s Camp Detrick, a US Army installation specializing in medical and biological warfare research. Others took employment located throughout the county and region as government jobs were becoming more plentiful. GI Bills assisted veterans in completing education and securing loans for such things as automobiles and houses. This became a contributing factor for an increasing population characterized as “the Baby Boom,” in turn, bringing a greater demand for improved educational facilities, medical amenities and of course, social services. As many families began migrating to the rapidly expanding suburbs, optimism was the hallmark of the new age—an age of grand expectations. The Roosevelt administration of the previous decade generated a set of political ideas—known to later generations as New Deal liberalism. This remained a source of inspiration for years to come. Community Chest campaigns over the next few years had cash collections that nearly doubled those before the war.

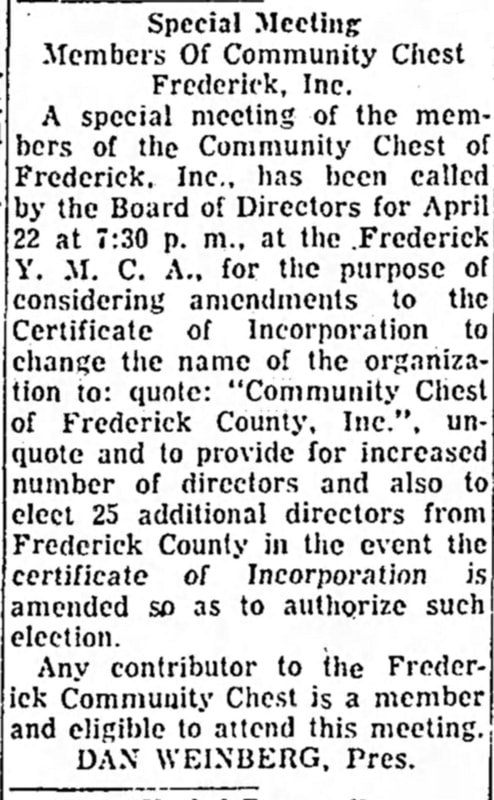

Before decade’s end, more successful drives were enjoyed and another non-profit member was accepted for membership. This was the Esther E. Grinage Kindergarten, the first such pre-school opportunity for African-American children in modern times in Frederick. Much of Frederick was still segregated at this time. This was exemplified here in Frederick with public schools, hospital entrances, parks, restaurants and movie theaters. The gesture of support by the Frederick Community Chest spoke volumes during a difficult time of racial inequality visibly present at the local, state and national level. The 1949 campaign drive was also noteworthy and historic in the fact that it marked the first time Frederick’s local Black population became involved in earnest with the organization that would one day become known as the United Way. As the Community Chest entered the decade of "the Fabulous Fifties," Harry Truman would be followed as president of the United States by the Republican war hero, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower. He was a moderate who did not attempt to reverse Franklin D. Roosevelt's "New Deal" programs such as regulation of business and support for labor unions. President Eisenhower actually expanded Social Security and built the interstate highway system. This was also a time of confrontation and fear as the capitalist United States and its allies politically opposed the Soviet Union and other communist countries—the Cold War had begun. Community Chest drives would continue throughout 1951-1959 with an annual average collection of $52,000. Each year now brought a new Frederick Community Chest president to the forefront. Names would include Glenn T. Swisher (Comptroller-Potomac Edison Co.), Paul McAuliffe (Manager-Francis Scott Key Hotel), Niemann Brunk (Owner-Frederick Produce Co.), Byron Winebrenner (Comptroller-Frederick Produce) and Charles S. V. Sanner (Insurance Agent).  As locals would first see the emergence of a singer named Elvis Presley and a re-designed Chevrolet automobile, the Community Chest’s Board of Directors under president (and local attorney)Parsons Newman decided to re-tool their own organization on a county-wide basis. They also instituted the “United Fund Campaign” for the entirety of Frederick County. Local Farmers &Mechanics Bank President Benjamin L. Shuff was appointed campaign chairman, and put together the first countywide campaign. Another historic element of this campaign was the first-ever use of a payroll deduction plan for employee donors. On September 25th, 1957, a well-attended dinner meeting of the Frederick County division of the Community Chest was held at the Francis Scott Key Hotel. Among those in the attendance were 50 area captains and election district chairpersons of the campaign from rural areas around the county. The keynote speaker was past Chest president, and campaign chair, Charles S. V. Sanner. He was a one-time special assistant to the Fort Detrick commandant, along with being a realtor and insurance agent. Sanner gave an overview of the Frederick Community Chest’s first 20 years in Frederick from formation to the recent countywide drive. He also spoke about the member agencies that the campaign helps each year. “Respect for the privacy of the individual recipients of our aids,” Sanner said, “has prevented many of our county services from being generally known to the public. These are not old-fashioned charities but vital public services and character building organizations.”

|

AuthorChris Haugh Archives

February 2024

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed