HSP HISTORY Blog |

Interesting Frederick, Maryland tidbits and musings .

|

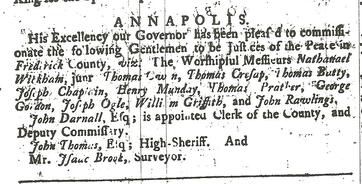

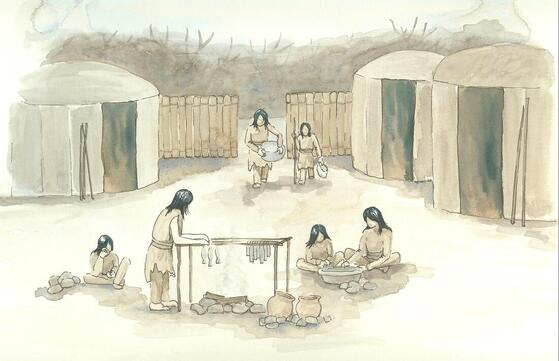

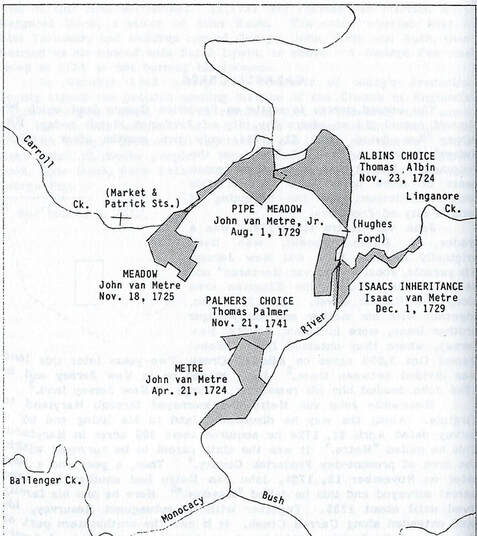

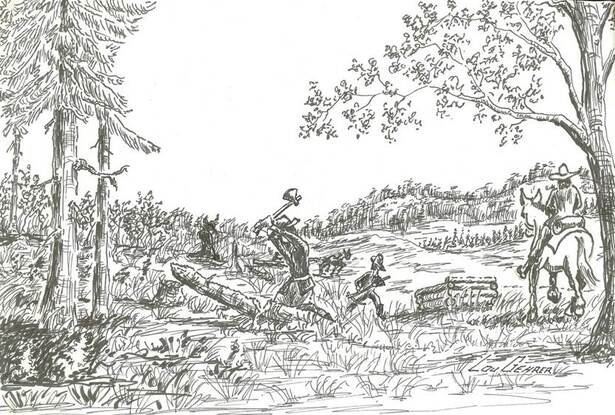

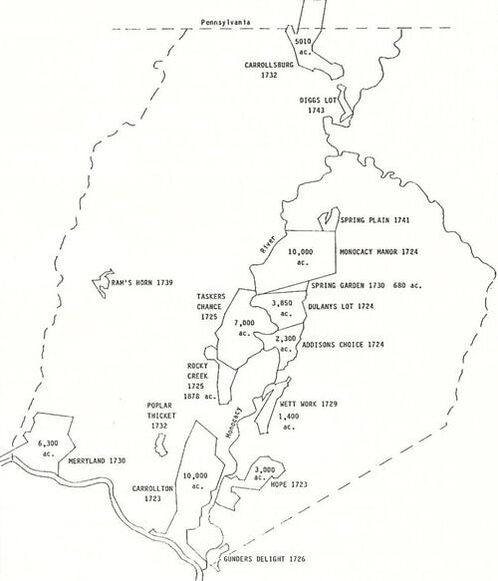

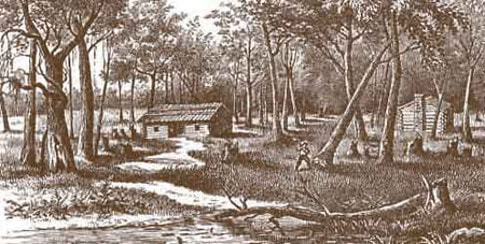

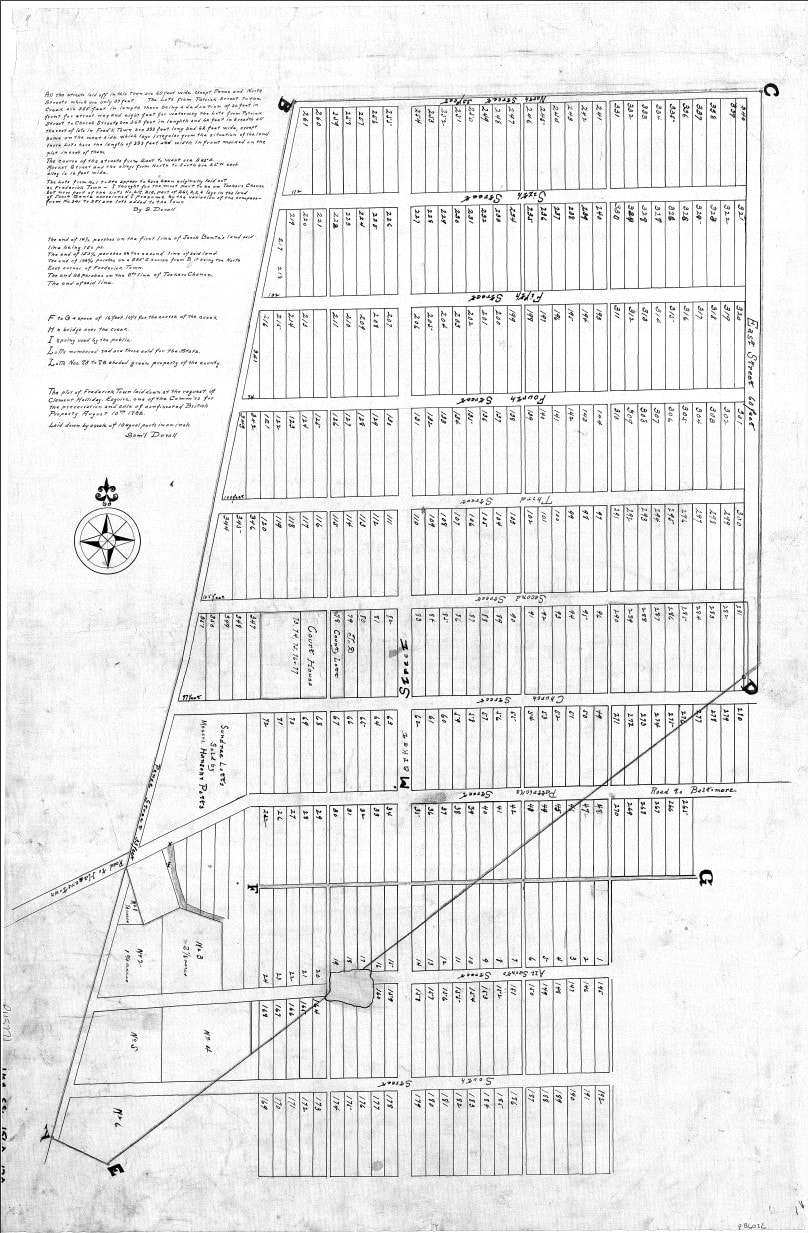

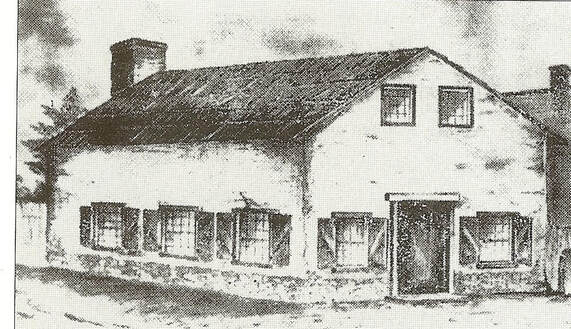

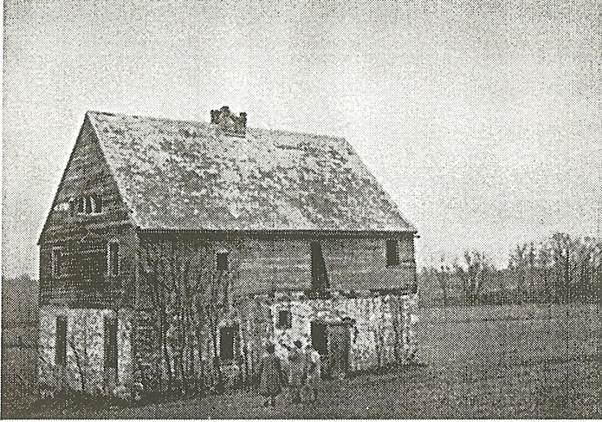

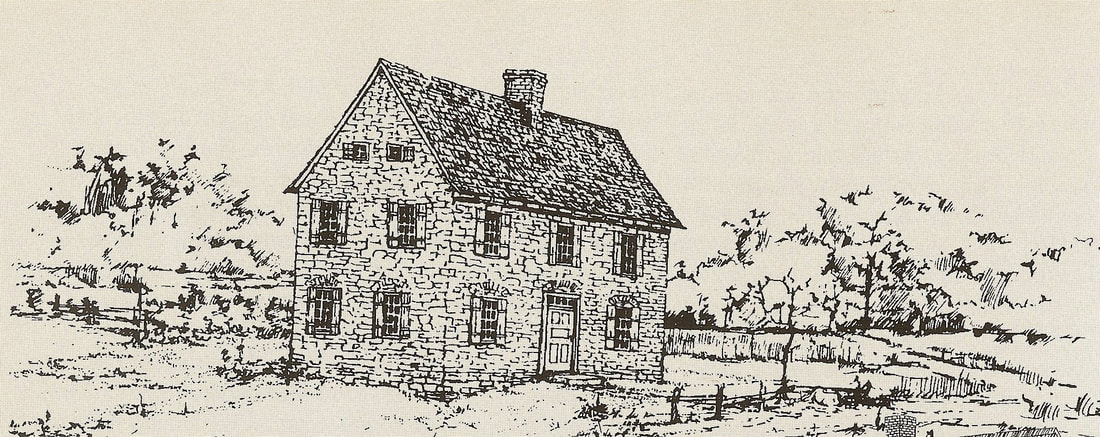

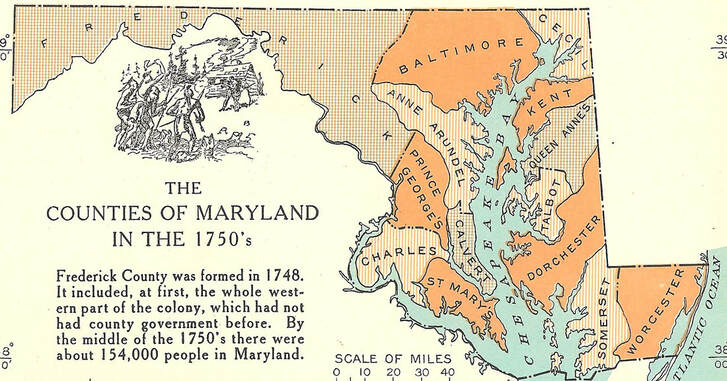

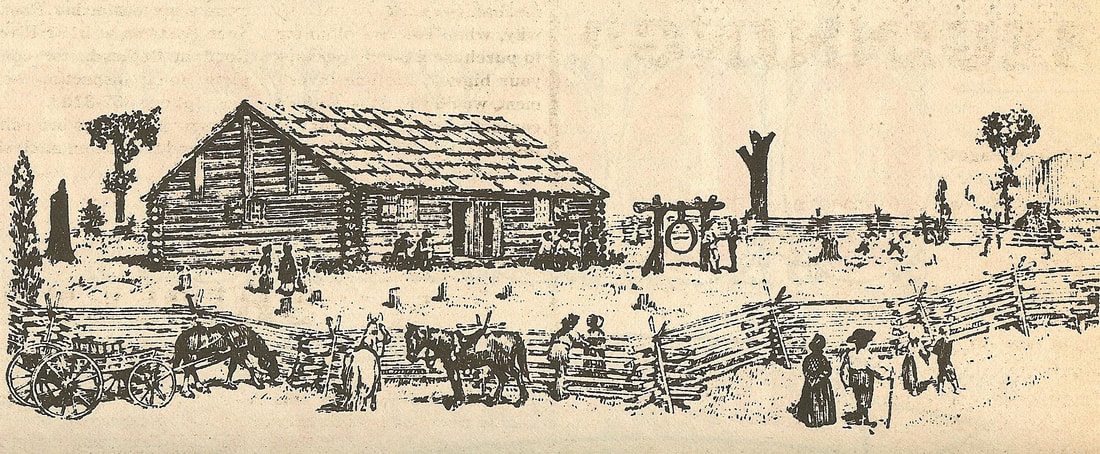

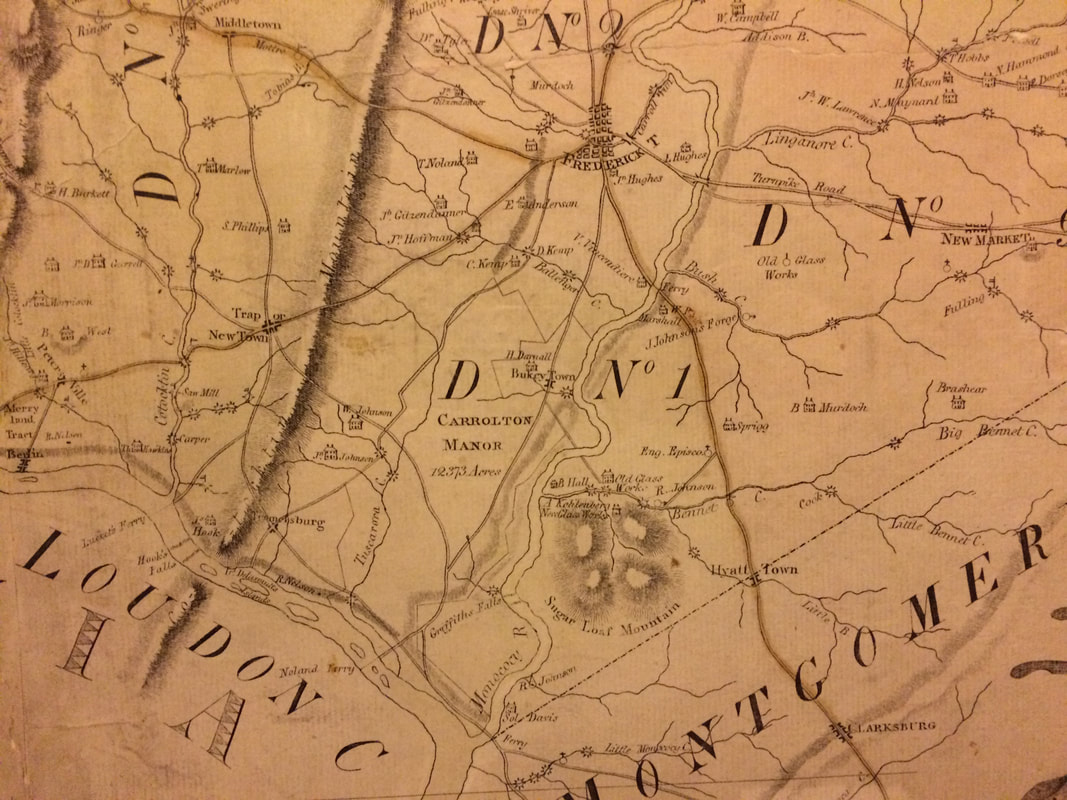

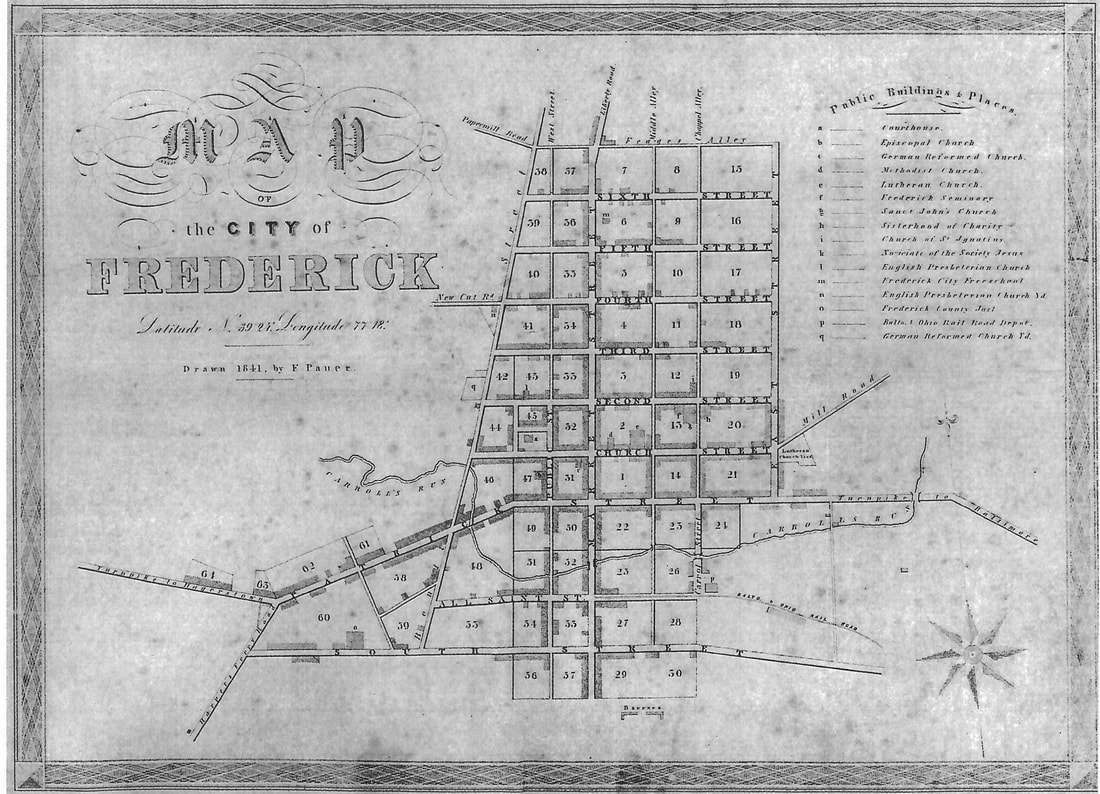

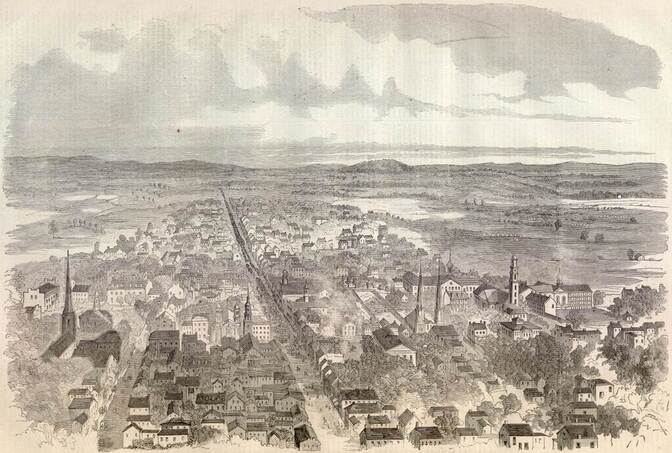

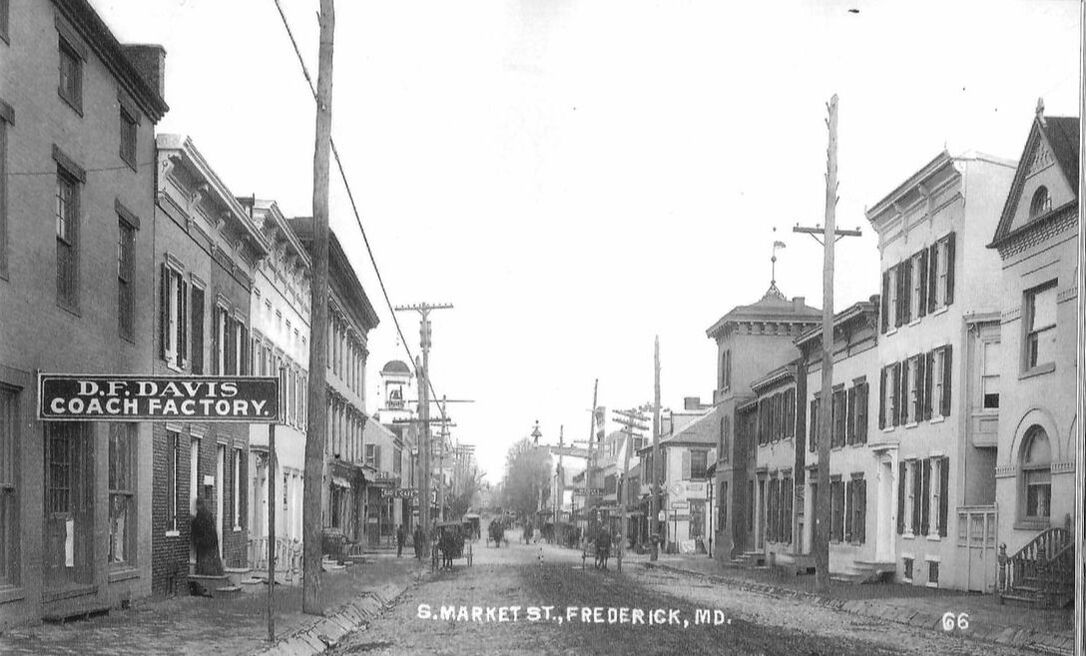

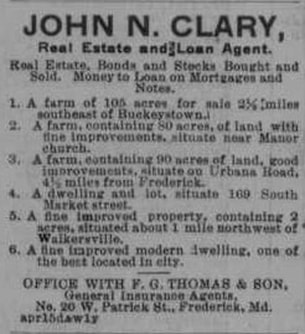

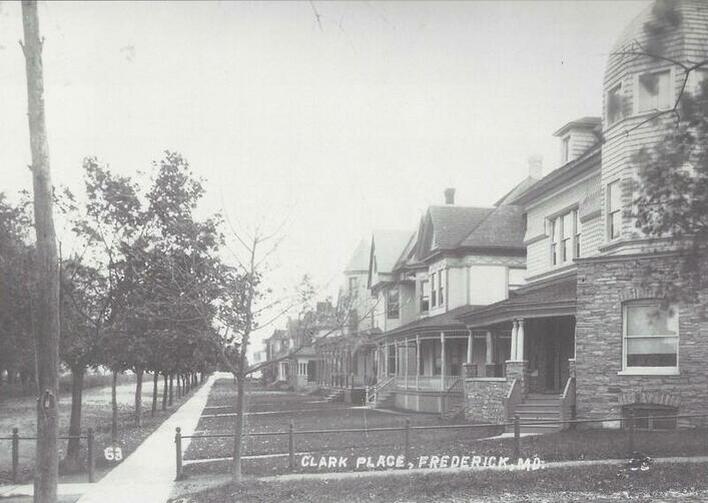

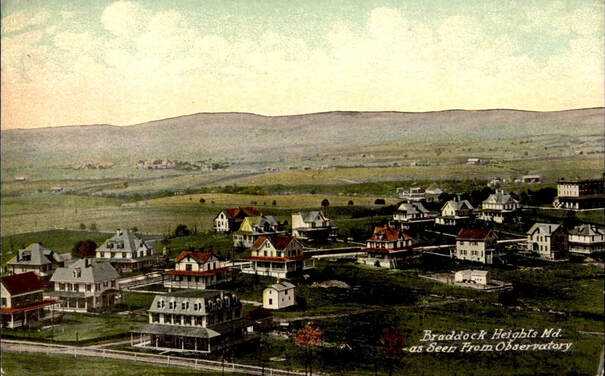

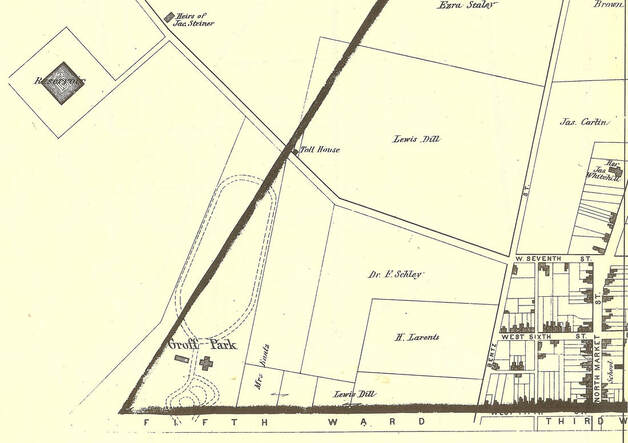

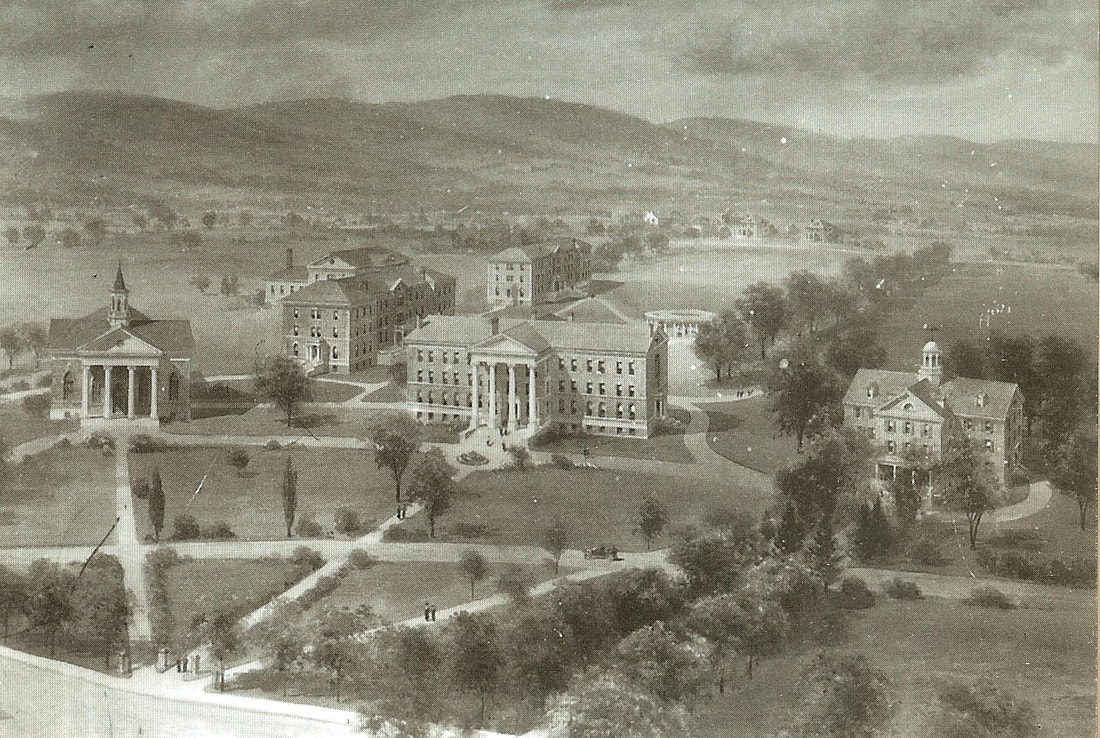

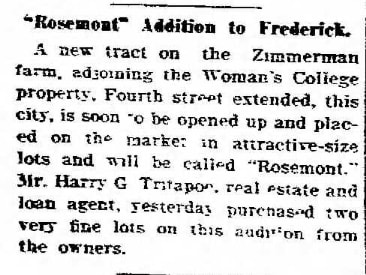

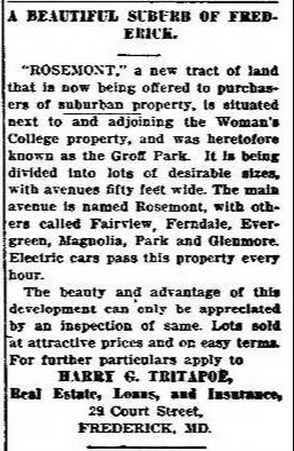

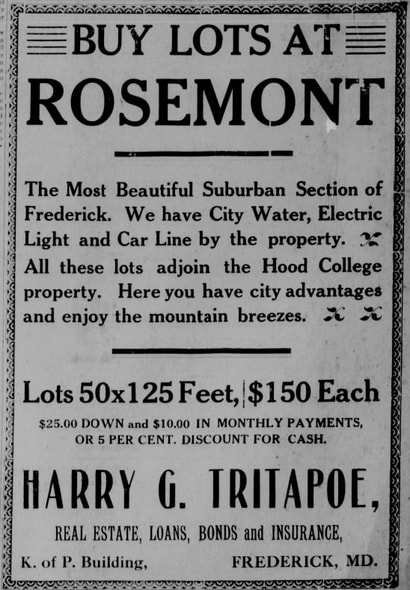

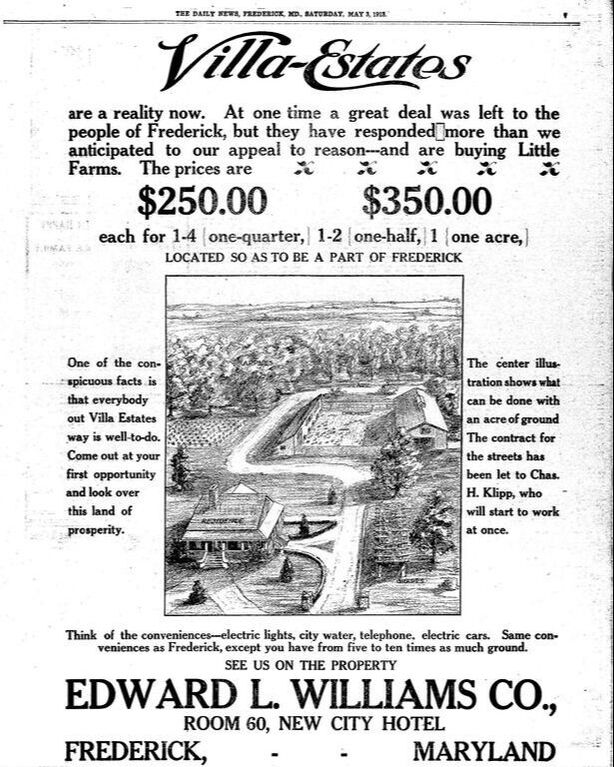

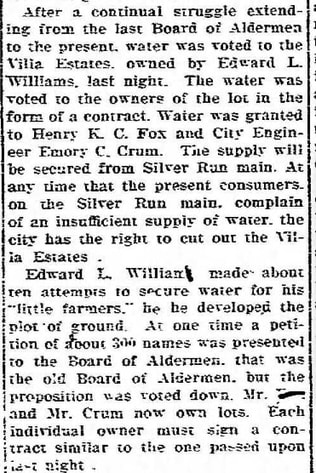

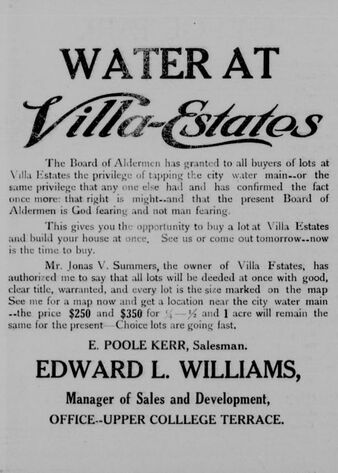

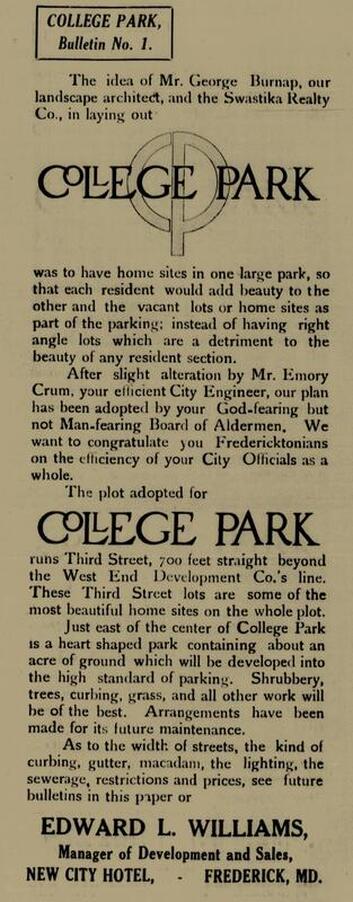

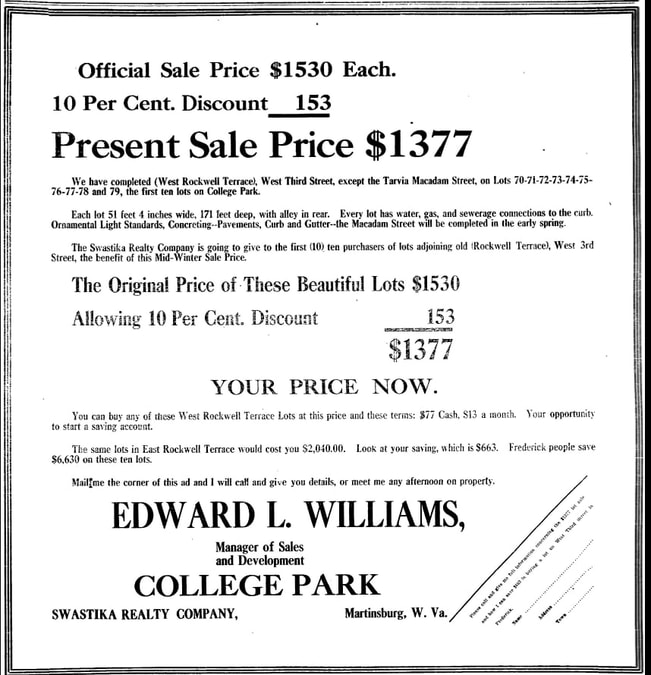

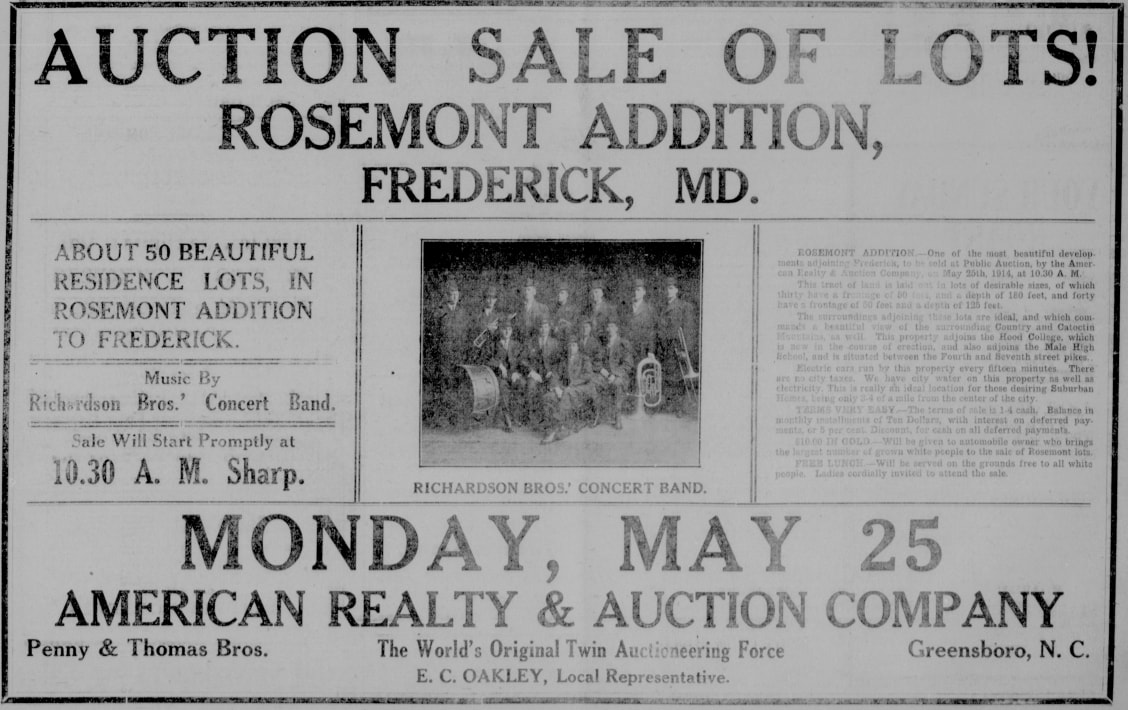

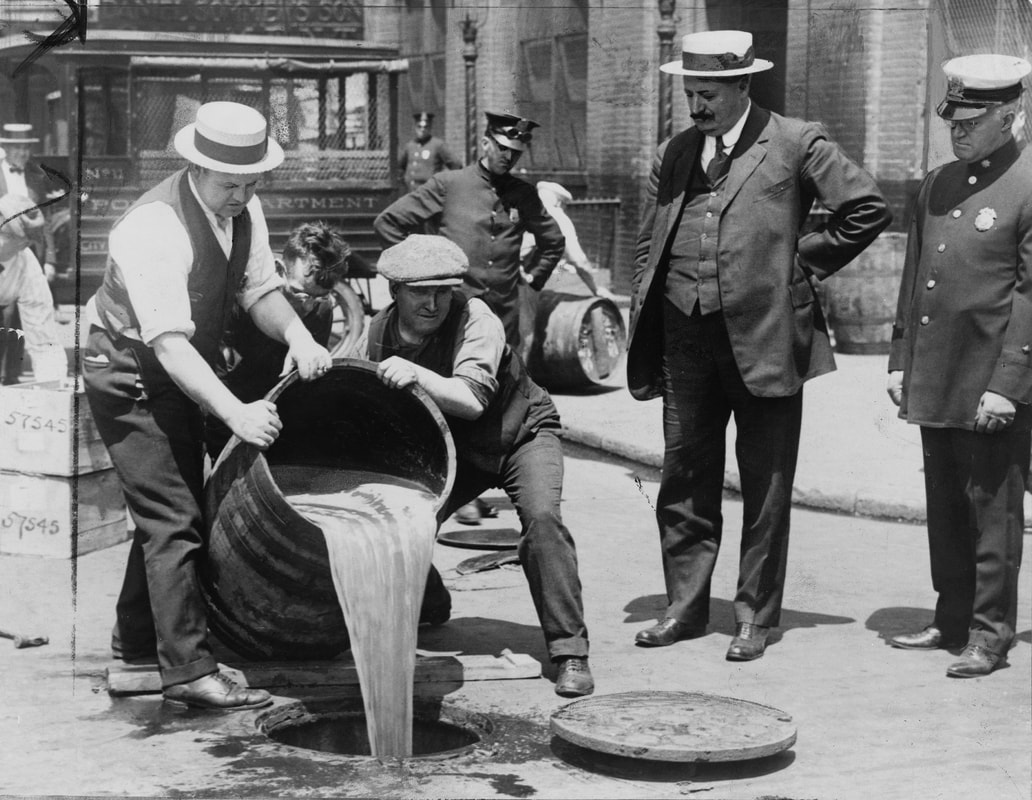

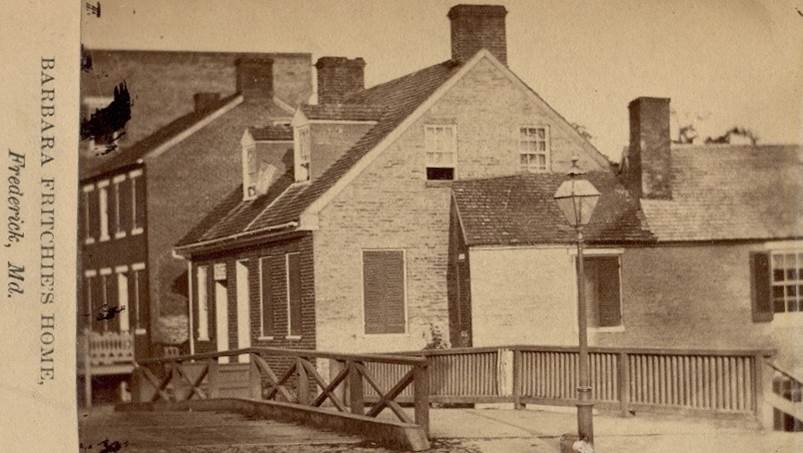

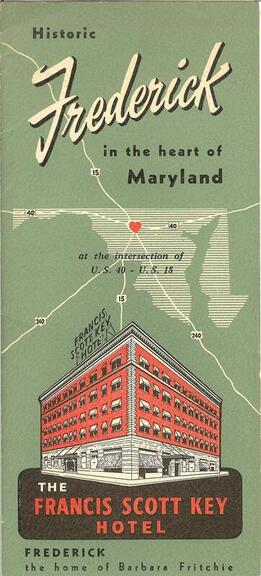

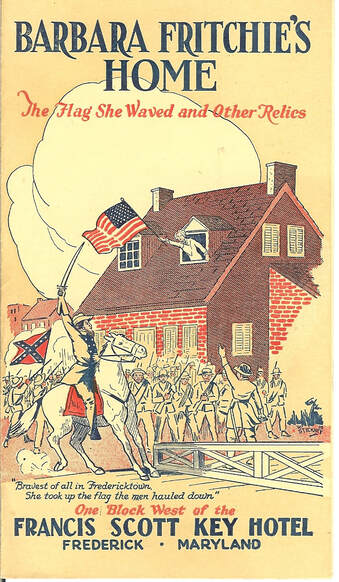

This year holds a special anniversary in the annals of Frederick County history. It’s something a little different, and not the typical commemoration or sacred remembrance of a town founding, a specific building construction, a notable entertainment event, a local battle, monument unveiling, catastrophic tragedy, patriotic flag waving or sports championship of some kind. The year 2022 marks a great accomplishment that certainly hits “home” for county residents—both literally and figuratively. Locals will recall the birth of an organization founded a century ago on February 9th, 1922 with the purpose of advancing professionalism in the business of Real Estate. Originally incorporated as the Frederick Real Estate Board, this entity is today known as the Frederick County Association of REALTORS® (FCAR). Over this century, this organization has done so much more than its primary role of helping to provide humans with shelter, one of the foremost human necessities. The official mission of the Frederick County Association of REALTORS® is to “support and enhance its members’ professional objectives and adherence to the Code of Ethics. The Association strives to achieve this undertaking by providing quality education for members, promoting professional and ethical behavior, and fostering a positive image within our community. The Association is committed to the local Frederick community and strives to promote the role of REALTORS® to the public. Members work with legislators to be involved in the political process and protecting property rights. FCAR works closely with Maryland REALTORS® and the National Association of REALTORS® to achieve these goals.” In an effort to properly tell the story of the Frederick County Association of REALTORS,® one needs to first understand and appreciate the uniqueness of the organization’s “life-blood” and prime product—real estate here in this part of the state and country. Frederick County, Maryland boasts one of the most scenic, historic, culturally vibrant, and progressive landscapes in the entire country. Places such as this attract special people as residents, and naturally possess like professionals to guide and assist these unique residents in finding the right home or business location. FCAR continues to gain REALTORS® having a strong passion for their product and trade amidst a backdrop of natural and manmade beauty. The Frederick region’s historic roots in real property acquisition & selling extend deep. Land here is particularly valuable. Over the past century, high quality real estate professionals have been responsible for helping to build the county’s communities through their passion and integrity for the trade, while giving selflessly of themselves. Here, you will find a continuing effort to make Frederick County the best place to work and live. This has been a constant for the last 100 years with the existence of the Frederick County Association of REALTORS,® and the Frederick of today is a direct result and continuation of a community-minded base and foundation laid down at the time of Frederick’s initial founding in the mid-1700s. The Earliest Residents Appreciating the uniqueness of land and real property calls for one to take a look at the geography, archeology and anthropology of the area that comprise today's Frederick County, Maryland. Geologic events occurring over hundreds of millions of years helped create a region consisting of two distinct mountain valleys, well-wooded and teeming with game at the time it was first traversed by humans. The area has been lauded for its agriculturally-rich soil and a network of waterways boasting salubrious rivers, creeks and streams. These tributaries spread-out across a rolling landscape to provide ample water supply for a vast habitat of humans and animals, while later aiding trade endeavors such as farming and light industry. Beginning roughly 10,000 years ago, the nearby Chesapeake Bay formed as glaciers receded northward. This caused the Susquehanna River to overflow a once humble river valley existing between both shores of today’s Maryland. Meanwhile other rivers further west of the bay would experience rejuvenation, including the Potomac River coming from the northwest, the Monocacy River flowing through the Monocacy (Frederick) Valley and Catoctin Creek flowing through what would become known as the Middletown Valley. These natural features brought Native American people to this region, and continue to attract residents to this day. Approximate dating shows that people were likely here in this area as far back as 8000 BC according to archeologists. The first were nomadic and followed large game animals. Later, ancient peoples would travel here from great distances from various places in search of indigenous lithic materials for use as spearpoints and tools. While here, they would inhabit the first “homes” of Frederick County in the form of isolated rock shelters—natural rock overhangs. These would serve both travelers passing through much in the way hotels operate today as temporary lodging. The first permanent resident populations seem to have settled here around 1000 AD, in what is called the Woodland Period of human habitation (roughly 1000 BC-1600 AD). This group would occupy areas adjacent the Monocacy River such as significant archeological sites discovered near Biggs Ford (north of Frederick City) and Rosenstock Farm (east of Frederick City). One could say that these locations were our area’s first “community housing developments.” Many names from the Indian tongue remain today and have been applied to more modern estates and housing communities in the present. These include Potomac (“Where the goods are brought in”), Catoctin (“Mountain of much game”), Linganore (“It melts in springtime”) and Monocacy (with two meanings: “Well-fenced garden” or “River of many bends”). It is safe to say that several of the things that influenced native peoples to settle here are the same things that would inspire future residents to do the same—from the colonial period up through the present day. Contact with Europeans by the native people would follow in the 1600s, at which time, “history” began being duly recorded by explorers such as John Smith of Jamestown, and the Calvert family, founders of the Maryland colony in 1634. Actual names would now be assigned to indigenous Indian groups such as the Susquehannocks, Piscataways, Senecas and Tuscaroras—distinct tribal groups known to have utilized the Monocacy and Middletown valleys for hunting and subsistence. As the white man encroached, coastal-Maryland natives were forced inland to an area looked at by the English colonists as “untamed, wild and dangerous.” The Piscataway and Tuscarora would establish small encampments and villages here in the early 1700s as Europeans continued building settlements along the Chesapeake Bay and lower Potomac River. Early Europeans in the Monocacy Valley Slowly but surely, European colonists began moving toward the interior of the colony, establishing manors and villages along major waterways connecting to the Potomac and Chesapeake Bay. Land speculators and colonial officials of the early 1700s wanted to take control of the interior and make these areas profitable for both themselves and the English throne. A handful of individuals began having land patented for themselves in the Monocacy Valley. In 1723, the Carroll family of Annapolis would have land surveyed in the southern Monocacy Valley in the shadow of Sugarloaf Mountain. This would become a 10,000-acre parcel that would take the new owners name of Carrollton Manor. The first settler to have land surveyed for his own home residence in the Monocacy region occurred in 1724. Arthur Nelson bought a tract of land along the Potomac River near present-day Point of Rocks. Meanwhile, a Dutch trader from New Jersey, by the name of John Van Metre, became the first of his profession to acquire a title to the land on which he lived. He had 300-acres surveyed which was situated along the west bank of the Monocacy River. A year and a half later, Van Metre would have another parcel along Carroll Creek surveyed and named “Meadow.” This property would eventually become the southeastern part of a bustling village on the western frontier. The proprietors of Maryland could not accomplish their task of westward expansion into the interior with typical English immigrants and landed gentry ingrained in utilizing the manor farm, or slave plantation, model. Most were somewhat hesitant to leave the navigable waterways adjacent the bay and lower Potomac and Patuxent in southern Maryland. The proprietors of the colony needed people who were especially hard-working, brave and industrious. In the new world, faith and frugality would be guiding principles. German and Swiss immigrants seem to fit the bill as had been witnessed to the north in William Penn’s Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. The 1730s marked a tremendous level of German immigration to the New World. Many landed in Philadelphia, a popular point of disembarkation. William Penn went to great lengths marketing his colony as a religious safe haven to all, starting with members of the Quaker religion years before. These German immigrants would populate the area northwest of Philadelphia, including Germantown, and others further west ultimately comprising an area later coined as “Pennsylvania Dutch Country.” Most of these early German families had first settled in Pennsylvania near places like Lancaster (established in 1730). By the latter part of the decade, some of these people would cross into Maryland and travel the German Monocacy Road, settling in the area between today's Thurmont and Lewistown. A gentleman named Johann George Gump would be the first of these German immigrants to reside in the Frederick Valley. This occurred by the year 1736. The western regions of the Maryland colony offered prime opportunities for wealthy land speculators hoping for future monetary gain through crops and land rents. However, buying these parcels could be a risky business decision because no one was certain if this wilderness could be turned into thriving settlements. As noted earlier, Maryland’s western interior was characterized by many English colonists as wild terrain, inhabited by countless other forms of wildlife and not fit for the style of living and business routinely conducted in the “more civilized” eastern and coastal areas of the province. One of the earliest land prospectors willing to “take a chance” on the western wilderness of the Monocacy Valley was an Annapolis gentleman named Benjamin Tasker. The son of an English immigrant, Tasker was a prominent businessman and well-known lawyer. He had previously served as mayor of Annapolis and was a member of the provincial government’s Upper House. In years to come, Benjamin Tasker would preside as President of the Governor’s Council of Maryland, Commissary General and governor of the province. Tasker requested a parcel of the untamed western land from Lord Baltimore. On June 9th, 1727, he received the patent for more than 7,000 acres along the Monocacy River, one of the most fertile land parcels in the province. He named his tract “Tasker’s Chance.” This parcel had originally been surveyed in April of 1725. The lot began at “a bounded beach tree, with nine notches standing at about two perches from the banks of the Monocacy River and about six perches from the mouth of Beaver Creek.” In later years, the name of Beaver Creek would change to Carroll’s Run and finally, Carroll Creek. This would soon encapsulate much of the area of a town to come. In the early 1730s, people began settling on, and near, Benjamin Tasker’s property. The fertile land was especially good for farming. As stated before, the area’s earliest European residents came mostly from the north through Pennsylvania. However, there were those that would travel from southern parts of Maryland such as a group of English-speaking people who settled in the Urbana vicinity. Many other early English families made their way here from the mouth of Rock Creek through what is today Montgomery County. Of the settlers that came here, prime reasons for their relocation revolved around the opportunity to obtain more land at cheaper prices, especially important for large and extended families. They were also attracted to the locale’s rich, limestone soil, perfect for farming. Eight German families could be found “squatting” on land just north of today’s downtown Frederick and west of the Monocacy. As far as shelter, these settlers started off in huts, sheds and log cabins. Over time, they eventually enclosed these log cabins, or would build an additional cabin or better house next to it. In 1733, some 30 people from New York joined the German and English colonists already here in clearing the surrounding country and settling the land to the east of the Monocacy River and the German squatters to the immediate west. Susanna Beatty, a widow in her fifties, and eight of her children re-located from the Kingston, New York area. The Beattys acquired 1,000 acres of property on a tract of land next to Tasker’s Chance which had been called Dulany’s Lot. This was owned by a prominent Annapolis lawyer and speculator named Daniel Dulany. The Beatty’s cleared their land, located in the middle of what would later become Ceresville and west of today’s Mount Pleasant. The Beatty-Cramer House on MD route 26 (east of Israels Creek) still stands today and represents the county's oldest known house. The first European residents, the fore-mentioned Van Metres, left roughly in 1735. They spread the word to others about the importance of this area and showed that tracts could be surveyed and patented from the Calverts. They had paved the way for the Beatty family as well. The apocryphal story holds that many of the early immigrants of German stock were said to have been passing through en-route to the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, but upon seeing the beautiful landscape, were instantly reminded of the geography of former homelands in Germany and decided to go no further. Lord Baltimore offered settlers a fair agreement by which each family would receive 200 acres, only paying a rental of 4 shillings for each 100 acres, the first payment due at the end of three years. In today’s terms, a British shilling is roughly worth 24 US cents. Daniel Dulany, the Elder and Frederick Town For one reason or another, Benjamin Tasker decided he no longer wanted his western land holding. On June 11th, 1737, he offered to sell "Tasker’s Chance" to a group of German settlers already living on the property. Tasker wanted 2,000 pounds for the land (roughly $2,500). Unfortunately, the six men, Abraham Miller, Daniel Frantz, John George Loy, John Jost Smith, Peter Laney, and Jacob Steiner, did not have the money. Seven years later, this same group of settlers entered into an agreement with Daniel Dulany, the Elder who owned "Dulany’s Lot" to the east. Dulany and Tasker were not just business colleagues but also neighbors and friends. The German settlers asked Tasker to convey "Tasker’s Chance" to Daniel Dulany. On January 13th, 1745, Tasker sold his tract to Dulany, who soon after gave deeds to those living on "Tasker’s Chance" after they raised the money to pay him. Daniel Dulany was smart enough to know that the early people who came here were not wealthy. They depended on the little bit they could get from clearing the land and being able to accumulate a small amount of money. So, Dulany permitted the settlers to pay a small amount down, and mortgaged the remainder to them. "Tasker’s Chance" was just one of Dulany’s land holdings in this part of the province. In 1724, Lord Calvert had conveyed to Daniel Dulany the adjacent tract of 8,983 acres which made up “Dulany’s Lot.” He was also overseer of “Monocacy Manor,” a tract set aside for Lord Calvert and located north of “Tasker's Chance.” Daniel Dulany, in essence, was the area's first “realtor.” He was one of Annapolis’ most talented lawyers, born in 1685 in Ireland. Dulany had come to America with two brothers in 1703 after abandoning his studies at Dublin’s Trinity College. He arrived in Annapolis as an indentured servant, and served a four-year term with George Plater, an influential Maryland planter and attorney. Daniel Dulany’s service as a law clerk prepared him for a legal career and introduced him to the colony’s aristocratic planters’ society. In 1721, he was appointed attorney general by Governor Charles Calvert and was involved in the provincial government under Governor Samuel Ogle. Through investments in land, slaves, and an iron foundry, Dulany amassed a great fortune. With the capital means to back himself, he would become one of the country’s first land developers, having bought several parcels in western Maryland for the purpose of gaining profit through resale and renting. In September 1745, Daniel Dulany had part of his newly acquired “Tasker’s Chance” surveyed. He planned to lay-out a town on both sides of Carroll Creek on land returned to him by early settler John Jost Smith, who left the area. The vacant 260-acre parcel was in the south-central portion of “Tasker’s Chance.” Dulany named his proposed settlement Frederick Town in honor of Frederick Calvert, the 12-year-old son of Charles Calvert, or Lord Baltimore. But it is more likely that the chosen name was a compliment to Frederick Lewis, Prince of Wales, the son of George II and father of George III. Frederick Lewis was an important figure in public affairs in England and heir apparent to the throne at the time of the settlement of Frederick Town.  In 1745, Dulany assigned a group of commissioners to design the new western town. They wanted Frederick Town’s streets to run toward the cardinal points. There was already one road going through the new town, running from Pennsylvania to Virginia. This became known as Market Street, because a market would be established here. Another major street would intersect this road north of the Carroll Creek which it paralleled. This would receive the moniker of Patrick Street by the town founder, said to have been done to honor a prominent cousin, Dr. Patrick Dulany, a famous reverend and theologian living in Ireland. The new town was divided into 166 lots, laid out primarily north to south, with sizes ranging from 60 to 63 feet wide and 355 to 395 feet deep. The few people who bought their own lots paid two pounds, 10 shillings (about $3.20) with an annual ground rent of one shilling (roughly $.25) for 21 years and two shillings a year thereafter. A majority of residents leased lots, paying Mr. Dulany a quit rent of a shilling sterling. Frederick Town arose as the Maryland colony's first planned unit development. Daniel Dulany had a vision for his town and had to overcome challenges of being positioned in the backlands of the colony, while not having a navigable waterway. Regardless, he specifically began a unique marketing strategy of recruiting German immigrants from Pennsylvania and Europe. Dulany also started attracting English coming up from southern Maryland and the tidewater area of Virginia, looking for a new place to conduct business. The developer’s goal was to create a major trading market on the western frontier of the time. “Out of the Reach of Oppression” Early German settlers included the names of Brunner, Shellman, Kemp, Raymer, Grosh, Fout, Houck, Holts, Reich, Bentz, Brengle, Mantz, Conradt, Young, Kolb, and Getzendanner. These people had fled from the oppressive restrictions of their homeland to seek a refuge here for themselves and their families. They brought with them their language, culture, and industry. Another German family who made the long overseas journey was that of John Thomas Schley who history books claim built the first house in town in 1746 on East Patrick Street and Stein Alley (today's Maxwell Alley). This log and stone structure was two-stories high and had a gabled roof. Schley came to America for religious reasons and was the leading member of the German Reformed congregation in this new settlement. In 1748, Schley and his congregation built a log church on a lot that ran between West Church and West Patrick Streets donated for the purpose by Daniel Dulany. Frederick's founder donated lots to multiple congregations as he knew that these would serve as the centers of religious, educational and social life for these settlers living on the western frontier at the time. One of the area’s earliest settlers, Jacob Steiner, or Stoner (1713-1748), was one of the six men who tried to buy “Tasker’s Chance” in the late 1730s. Of the 19 individuals who initially received deeds from Dulany in 1746, only Steiner received more than one parcel. He held three lots, all located northeast of the newly laid-out town. Steiner operated a mill near the mouth of the Tuscarora Creek and named his lands “Bear Den,” “The Barrens,” and “Mill Pond,” the latter on which he erected a late medieval-style stone and timber dwelling. The ruins still stand amid the Worman’s Mill community. Steiner built the town’s first brick structure and later it was used as a tavern. The two-story building sat on the southwest corner of the village square at the intersection of Patrick and Market streets where Colonial Jewelers is today. One more immigrant of note to speak of was Joseph Brunner, who, with his family, immigrated to America in 1729 from a home in Schifferstadt (near Mannheim) Germany. The family landed in Philadelphia and eventually arrived in Maryland by 1744. Brunner bought 303 acres of land from Daniel Dulany for 10 pounds in 1746. He named his tract “Schifferstadt” after his native home. His son, Elias, completed a stone house on the property in 1756 which still stands today and serves as a unique architectural museum. It typifies German colonial architecture with two-and-a-half foot-thick walls, hand-hewn oak beams, exposed half timbering, and cross-and-bible doors with highly wrought elbow locks and hinges.  Daniel Dulany promoted his growing town by sending advertisements to Lord Baltimore, who in turn circulated these in Germany. In these inducements, Dulany used the immigrants who had already settled in Frederick Town to give glowing testimonials about his land and good will. The Germans greatly influenced early Frederick where the native language was more commonly spoken here than English. The style of houses and barns built also reflected German craftsmanship not English. Together with English and Scotch-Irish immigrants, the Germans forged the foundation of the small, land-locked village 40 miles from the nearest port. Some may have expected that the varied interests, habits and prejudices of these different cultures would have kept them apart. This was not the case as these pioneers found themselves in a wild country living near sometimes hostile Indians. The settlers faced all the difficulties and the dangers of frontier life. In spite of this, Frederick Town became a thriving community, attracting many tradespeople, including weavers, tailors, shoemakers, blacksmiths, and wheelwrights.  Maryland Gazette (Dec 14, 1748) Maryland Gazette (Dec 14, 1748) A New County At the time of its founding, Frederick Town was part of Prince George’s County which, along with Anne Arundel and Baltimore counties, encompassed most of the Maryland province’s western shore. With increased immigration to inland areas, the residents of western Prince George’s County petitioned the provincial government to form a new county. In 1739, Benjamin Tasker introduced the first bill to create a new county. After nine consecutive, annual attempts, the proprietary government agreed for Daniel Dulany’s fledgling village to serve as the county seat, helping to bring additional value and prestige to his planned community investment. Frederick County was formed by a legislative act on December 10th, 1748 and included the entire western part of Maryland. A county court system was established here in Frederick Town with sheriffs and justices of the peace. A courthouse and jail would be built. The commissioners purchased lots 83-88 from Daniel Dulany in 1750, today this serves as the site of Frederick's City Hall. Travel Crossroads Frederick Town’s remoteness forced it to become an independent town from the beginning. Travel was difficult and distances great. The earliest settlers built their own farms and houses and provided for all their own needs. As Frederick Town grew, more craftspeople settled here to provide services and supplies to the residents. Tailors, scriveners, jewelry makers, printers, hat makers, and tanners were among the leading businesses found in town. Many rented, while some owned these examples of Frederick Town’s earliest commercial real estate. The main thoroughfare to and from various colonies passed through Frederick. In a few years, a public road was built from Frederick to Annapolis. The town became a stopping place for weary travelers. To accommodate the many visitors, taverns were built along the route. During this period, Annapolis was an important trading port and the road from Frederick was used by area residents to haul tobacco and flax to the shipyards. Frederick Town expanded rapidly, soon becoming the second largest town in Maryland, an honor it continues to hold today. Thanks to British Gen. Edward Braddock’s ill-fated mission during the French and Indian War, the first road west had been established and carved out to Cumberland. This later would become the National Pike, utilizing Frederick’s Patrick Street. Years later, during the American Revolution, a British military member wrote of this unique residential and commercial setting in his journal: "Frederick Town is a fine large town and has a very noble appearance as the houses are mostly formed of brick and stone, there being very few timbered buildings in it; it contains near 2,000 inhabitants, chiefly German." -Lt Thomas Ansburey, 1778 The community continued to grow as the new country further formed itself following the American Revolution. As for realty pursuits with issues such as land and home sales, transfers, building, etc., people were traditionally selling and buying on their own accord with official documentation being approved and stored at Frederick County’s courthouse. Sometimes a lawyer was involved, sometimes not. Regardless, it continued to be a good place to be if one was in the legal profession as the seat of county government and considering the abundance of court transactions necessitated in a large county brimming with growth. More villages had sprung up around the county and served as centers for farm shipping and markets for the surrounding countryside. Along the National Pike, Middletown gives its founding date as 1767 and New Market was laid out in lots in 1793. Libertytown arose in 1782 along the Liberty Road. In northern Frederick County, Emmitsburg came to be in 1785, and Mechanicstown (later named Thurmont) came in 1803. To the south, a gentleman named Leonard Smith would be responsible for laying out two more locations: Jefferson in 1774 and Berlin (later named Brunswick) in 1787. Buckeystown dates from the 1780s on the early land grant of Carrollton Manor. The 1800s The turn of the century came in 1800 and in a little more than 50 years since Frederick Town was founded, the village had quickly grown from a cluster of settlers into a thriving community, drawing the attention of prominent visitors and politicians. Its residents, mostly hardy German immigrants, rose above an unfriendly environment, so far away from a trading port. It had begun as a place of dense woods and wild animals, not to mention the residents having to endure early threats of Indian attacks and two major military threats with European foes, with a third to come in 1812. Frederick Town became an incorporated city in 1817, and the county continued to grow as the National Pike further took form. Settlers and goods made their way to, and through, town in directions east to west and north to south. The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad arrived here in 1831, as did the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal.  Early image of the B&O with open air passenger cars Early image of the B&O with open air passenger cars Settlers and goods made their way to, and through, town in directions east to west and north to south. The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad arrived here in 1831, as did the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal. Both entities gave rise to the previously mentioned Berlin, and another hamlet on the Potomac River that would take the unique name of Point of Rocks. Later in the century, train activity shaped Ridgeville, (eventually renamed Mount Airy in 1894) and further advanced Thurmont in terms of trade and tourism, as a cool-air, mountain retreat. Daniel Dulany's community turned 100 in 1845, a time of renewed building with unique public structures such as churches and schools, and additional floors or amenities to residential buildings. In this latter case, some original dwellings were replaced with modern architectural designs. Some of the other towns of the county would become incorporated during this century and further refined through progressive means. A brief, but major, interruption came mid-century with the American Civil War. Residents saw large armies come through hometowns, and in some cases experienced camping regiments, skirmishes and battles. A return to normalcy would eventually take place, and agriculturally based, light industry evolved further in the form of leather tanneries, sanitary dairies, canning companies and fertilizer and limestone works. Iron manufactories, a knitting mill, brickworks, and a major brush company would eventually arise here. In addition to farming, blue collar and professional jobs were available, and homes were certainly needed to house these individuals. Community building continued to grow in earnest thanks to churches, fraternal organizations and benevolent charities. In the City of Frederick's overview history by Diane Shaw Wasch and found on the City's website, the author states: "Plans for residential development beyond the established city grid began with the platting of Clarke Place on the south end of town in 1894. The plan for Clarke Place was a sign of the suburban development that would take hold in the early twentieth century, with large single houses on lots with deep setbacks from the street. Adopting the Late Victorian and Colonial Revival architectural styles, which emphasized larger individualized building forms, these houses signaled a distinctive new appearance in Frederick architecture. West of the city grid, street extensions shown on the 1897 Sanborn Fire Insurance Company map reveal significant plans for future subdivision. The end of the nineteenth century saw a renewed energy in Frederick’s development. The city was well established with thriving agricultural markets, particularly the emerging dairy market, as well as a diversified light industrial base, and a growing number of wealthy citizens associated with the railroads, business, and legal community. City streets were paved and lit with electric lights, and telephone service was available to city residents. The century’s end was punctuated with the formation of a hospital organization, dedicated to the construction of a state-of-the-art hospital on the north end of town, and the establishment of an inter-urban railway system that eventually connected with Emmitsburg to the north, Jefferson to the south, and most importantly, the railroad hub city of Hagerstown to the west." Real estate was bought and sold, sometimes with just a handshake. More often, a special professional's help became more and more desired to assist the home, or business, seller. Of course, many sellers sought a lawyer's counsel to consummate the deal, but there were those who prided themselves of being specialized salesman of dwellings and possessed the monetary means and connections to help gain loans or mortgages for would-be buyers. The profession of real estate broker began around 1900 here in the United States. The initial home sale records began here around 1890. There was actually an attempt to create the first real estate association in the country at this time, however, the effort failed. This exercise did help set a base for the process for later. There would be few, if any, set rules about who could work as a real estate broker. Hence, there were no licenses or professional certifications to become a registered broker, leading to dubious practices with many engaged in this line of work known as "curbstoners." Anyone could place a sign on a property to sell the house, creating a sort of “wild west” in real estate. This led to “curbstoners” placing signs in front of homes to compete amongst themselves and mortgage brokers, with the seller having to randomly pick a sign in which to help sell their house. 1900s Hometown USA While Frederick may have prospered near the end of the 1800s, the first 50 years of the next century would be one of slow growth. Some historians have described Frederick as a “sleeping giant” during the first five decades of the 1900s. Frederick still had the largest land area of any county in Maryland, but by 1920, Baltimore, Allegany and Washington Counties would exceed it in population. Many industries eyed Frederick as a potential business site, but town officials made no serious attempt to lure companies here. Therefore, the economy remained at a steady, if not declining pace, for the first half of the 20th century. Research shows that some of the older families and leading citizens of Frederick thought their peaceful town in western Maryland may be growing a little too fast for their tastes. There was a fear of too much industrialization, or dirty factories, coupled with the opportunity for railroad interests and trade unions to gain power from those whose forefathers braved the former trials of frontier existence. Other social influencers simply wanted to remain “big fish in a small pond.” Steps by some leading, local citizens appear to have been taken in discouraging major industry to locate, or build, here. Frederick simply remained known for its abundant farming efforts and possessing the oldest railroad depot in the United States, but certainly not the busiest. Two railroads came through Frederick County, but Frederick City was simply more of a terminus of spur lines as the railroads were never fully embraced. One could easily see the the growth and change brought with railroad and its influence on major industry in the nearby towns of Hagerstown, Martinsburg and Cumberland. All three places fast outgrew Frederick in population, along with economic and industrial prestige. Frederick would, however, incur considerable change in another way. Transportation innovations would help spark suburbanization. The advent of the automobile was key to this change currently sweeping the nation. Frederick (city and county) would also receive its own trolley line in 1896 which accelerated suburban and interurban activity. Into the 20th century, this form of mass transportation would link Frederick City to the Middletown Valley and Hagerstown to the west, and another trolley line would connect points north en-route to Thurmont from Frederick. Farmers could ship produce and milk to Frederick with greater ease, and necessity goods and items could be sent to those living in rural areas from the commercial seat of the county. While industry lagged, living amenities were enhancing the lives of Frederick residents. Perhaps this was the genesis of Frederick’s standing later in the 20th century as a bonafide “bedroom community.” A common constant was that Frederick would be seen as a great place to live and raise a family—a true “Hometown, USA.” Stately neighborhoods would begin to take shape in Frederick City as large homes began being built and pushing city limits outward. Referenced earlier, a row of thirteen homes along Clarke Place were constructed in 1894, exemplifying all the characteristics of the Victorian and eclectic eras of architecture. Located in the south end of downtown Frederick, off South Market Street, the development was built to front the newly built Maryland School for the Deaf, which occupied the former grounds of a barracks facility built at the time of the Revolutionary War. The unique neighborhood took the name of Clarke Place after local native, Gen. James C. Clarke—a past president of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal and several railroads including the Illinois Central Railroad. This area represented a new trend in the history and development of Frederick’s home design as most earlier examples fronted on the public sidewalk, featured a rear yard, and were two or three bays wide. According to Frederick City Planner, Christina Martinkosky: “The new neighborhood was unique in that it was the second planned extension to Frederick since the city was initially platted and the first not to mimic the long, narrow lots that typically define downtown Frederick. Instead, the development features wide lots that influenced the character of the neighborhood in several ways. It allowed for the construction of homes with large proportions and architectural features that were popular during the Victorian and Eclectic eras including front porches, projecting bay windows and towers. The generously sized lots allowed the large homes to be setback from the street and feature rear and side yards. In fact, deed restrictions on each property required that the new homes be set back 50 feet from the street and prohibited the construction of “double-houses” or offices. Over time, the neighborhood was built with homes designed in the Queen Anne and Colonial Revival styles, which were popular at the time and featured grassy lawns planted with Norway maple trees.” The area was previously part of farmland owned by Dr. Bradley Tyler and purchased by the South Park Villa Company, founded by Dr. Joseph A. Williamson, Harry W. Bowers, and Willard C. Keller. The homes along Clarke Place served as a precursor to the suburban development that would take hold in the early 20th century, featuring large, single-family homes on lots with deep setbacks from the street. Another example to follow included luxury housing being built on the northside of the 200 block of East Second Street. In 1903, the Jesuit Novitiate across from St. John’s Church was torn down. On this site, a handful of large homes were constructed. As trolley lines enabled people to move from the center of town, some relocated to Rockwell Terrace, a suburban development laid out and recorded in 1905 by local businessman Frank C. Norwood. Named after Elihu Hall Rockwell, former educator and native of New England, Norwood obtained the namesake’s property and house fronting on North Bentz Street at the head of West Third Street from a descendant. Mr. Norwood would move the house, thus opening West Third with a continuation thoroughfare he would call Rockwell Terrace. This area soon became the most desirable location in town, as the new neighborhood would be built under the leadership of Norwood and the West End Realty Company. To the west of Frederick, Braddock Heights was a byproduct of the trolley system as its parent company, the Hagerstown & Frederick Railway, built an amusement park atop Catoctin Mountain here. The location quickly grew as a resort for summer living. Attracted by the lush mountains and quiet atmosphere, prominent families and others, many of which had homes in downtown Frederick, built spacious cottages here that would capture fresh, mountain air and afford sweeping views of both the Frederick and Middletown valleys. Lewis Henry Dill (1821-1894), son of Joshua and Mary Dill, eventually came to own the property north of today's Dill Avenue and across the street from Frederick's first Presbyterian Church and graveyard. Mr. Dill's father was an innkeeper and War of 1812 veteran. Lewis lived on the northwest corner of N. Bentz Street on what was called (during his lifetime) the Almshouse Road, and eventually Montevue Road as it departed W. Fourth Street and headed in the direction of the former county home for aged and needy citizens. The street was also called the New Cut Road and Fourth Street Extended as well. The permanent renaming wouldn’t come until August, 1901 when Frederick alderman John Baumgardner suggested the name of Dill Avenue to replace the W. Fourth Street Extended moniker. It was duly accepted, and the rest is history. As for Lewis Henry Dill, he made his living as a farmer and large landholder. The College Effect The former Women’s College of Frederick announced plans in 1911 that Mrs. Margaret Hood had donated a parcel of land to the female learning institution for use as a new campus. This locale had once been known as Groff Park, home to a shooting club known as Deutsches Schuetzen Gesellschaft Park. This was a social and stock endeavor formulated by leading German-descended residents. Present-day Brodbeck Hall (on the campus of Hood College) served as the clubhouse for the group, which came complete with an old-fashioned beer garden to accommodate stockholders. The Civil War and lean times caused financial woes that the club could not rebound from, and apparently Capt. Joseph Groff, a local hotel keeper, purchased the locale. Hood College moved from its previous location on East Church Street to a new campus on the northwest part of town in 1913. This area was now destined to expand even further beyond Rockwell Terrace, truly the most desirable residential location in the city, away from the sights, sounds and smells of industry and trains primarily located in the southeast part of Frederick, containing the tanneries, grain mills, packing plants and canneries. Existing homes bounded Dill Avenue, an extension of West Fourth Street west of the intersection with North Bentz Street. The Zimmerman Farm was located to the immediate west of Mrs. Hood’s donated land for the college. Ninety acres would be purchased by local attorney Harry G. Tritapoe and business partner Eugene Sponseller. These gentlemen would lay out, and sell, building lots here in 1913. This subdivision would take the name of the former poultry farm --"Rosemont." Montevue Avenue would soon after take the name of the venture—Rosemont Avenue. Two gentlemen of particular interest in the Rosemont story are Elbridge F. Biggs and John M. Culler, who jointly bought eight building lots here in 1913. Their purchase constituted the entire 1st block of Fairview Avenue, north of Rosemont Avenue. Meanwhile, to the east of the immediate campus, fine homes began being constructed on the extension of West Fourth Street immediately next to the proposed campus and along Elm Street. This newly created street led to a new public school that would take the thoroughfare's tree-themed name. There had been some residential building activity on the east side of town already. Hamilton Street, across from the fairgrounds, and a few other lots in this vicinity had popped up on the old eastern entryway into town. East Fifth and East Sixth streets experienced residential growth as would North Market Street. The place to be, however, was the in the northwest part of town in proximity to Rosemont (Montevue) Avenue. Soon after Rosemont lots began being sold, other neighbors in this vicinity would “give up the farm” so to speak, allowing additional plans for development around the new education center of Hood College, which opened in 1913. Farmland would be purchased and soon gave way to two future subdivisions: “Villa Estates” and the aptly named “College Park.” Controversy erupted among some locals because this was being orchestrated by an outsider named Edward L. Williams from Martinsburg, West Virginia. He called his company “Swastika Realty." Some residents of Rockwell Terrace, along with local businessmen and others were outraged at this perceived “carpet-bagger” subtly challenging Frederick’s resident “big fish.” The neighborhood coined as “the Residential Showplace of Frederick” was now being challenged for supremacy by a new one, initially touted as having “the most picturesque views in the city.” Villa Estates was announced in late April of 1913 as being unique for having country style lots in which they could "have a lawn, chickens, a garden and fruit trees." Interested buyers were enticed by free trolley ride vouchers placed in the newspaper to encourage a visit to learn more. From the outset, Villa Estates, would be delayed and hampered by slander and blockages to a water supply, thanks in part to the current mayor and board of alderman. This became a major problem over the next year as Mr. Williams had been rejected by the city fathers after ten attempts to obtain water. A compromise came with a change of administration as Lewis Fraley won the mayor’s race in late 1913 and worked with his Board in the new year upon taking office. The necessary supply was allowed by summer of 1914. College Park had its own opposition as well as already stated. To combat sentiment, Mr. Williams hired noted landscape architect George Burnap to provide the architectural design, if approved. Mr. Burnap helped design areas of New York’s Central Park and was also responsible for Hagerstown’s City Park among many others. He worked as a landscape architect for the Office of Public Buildings and Grounds in Washington, DC between 1912-1917. His work in the nation’s capital includes Meridian Hill Park and the White House’ West Garden. A contentious meeting held at City Hall in early September 1913 resulted in the Frederick Board of Alderman giving the ultimate green light to this project. Soon, luxurious houses began being built along West Third and Fourth streets, west of Rockwell Terrace. Mr. Burnap employed a design of angled lots radiating around a central parcel shaped in the form of a heart. This particular “heart” plot would become Schley Park, named in honor of Frederick’s Admiral Winfield Scott Schley, a naval hero in the Spanish-American War. The Rosemont subdivision was the local challenger to Mr. Williams’ projects. Not as professionally handled as its rival subdivision projects, an advertisement appeared in spring of 1914 announcing an auction of 50 lots in this section north of Rosemont Avenue. This occurred just prior to the water approval for Villa Estates and was put on by the American Realty and Auction Company of Greensboro, North Carolina. Of note, gimmicks were used here in offering a free lunch which was a great incentive, but not more than the promise of $10 in gold for “the automobile owner who brings the largest number of white grown-ups.” The sale signified the future need for more scrupulous real estate practices. Mr. Williams clearly felt the wrath of his rivals and now wisely looked toward well-rooted local professionals to sell on his behalf. Beginning in May 1914, a new realty firm put up their respective shingle. This was Potts & Griffin. Two years later, this tandem began selling lots for Mr. Williams and the College Park Real Estate Company. New development plans would be slowed in the years of 1917-1918 due to World War I, but normalcy returned after the signing of the Armistice peace treaty in November 1918 and return of local soldiers in early 1919. Businesses flourished, and suburban residential development commenced as the period labeled “the Roaring Twenties” would soon take hold. Walker Neill and John J. Joliffe would purchase "Villa Estates" and take over sales here in 1919. Another gentleman named John N. Clary could be found selling lots in all three new subdivisions (Villa Estates, Rosemont and College Park) located northwest of town. Mr. Clary was a veteran in the industry with experience dating back to the previous century. Luckily the heated rivalry and real estate version reminiscent of “the Hatfields & McCoys” would end for not only the good of the community, but more so for innocent would-be buyers. The trolley, or Hagerstown & Frederick Railway, would change its name to the Potomac Public Service Company in 1922, and shortly thereafter to the Potomac Edison Company. Electricity and indoor plumbing were life-changing amenities. Homeownership would become further re-imagined. Frederick remained a peaceful city with tree-lined streets and devoted citizens working toward public improvements. The same held true with the smaller towns and villages throughout the county. This was a special place, and the year 1922 marked the start of a real estate-based organization whose timing was perfect for residents, old and new. Frederick was also a unique location to serve and accommodate visitors. Some were here on business, others here for pleasure, while many folks were just passing through en-route to some other destination by automobile. Regardless, it was hard not to be impressed with the look and feel of Barbara Fritchie’s town of “clustered spires, green-walled by the hills of Maryland.” The principal hostelry of town, the New City Hotel, was razed in early 1921 to make room for a new hotel. Under the leadership of local businessmen such as Charles McCurdy Mathias, Sr. and Col. David John Markey, a luxurious, six-story establishment would soon carry the name of another one of Frederick’s leading historical figures, Francis Scott Key, writer of “the Star-Spangled Banner.” The hotel would be built in 1922 and opened the following January. The facility was a “state of the art” amenity for its time and helped further proclaim the importance and potential of a community steeped in rich history and the American experience. Building in, and around, Frederick was booming. The controversies tied to the Villa Estates and College Park projects in allowing outside interests to dictate municipal policy was a great impetus to having “home rule” through and through. As stated earlier, this was the same reason the railroad wasn’t embraced nearly a century earlier. However, many saw that the unscrupulous practices of some locals, if left unchecked, could also have devastating effects on the future of a growing town originally began as a planned community on the colonial frontier of Maryland. Now was the perfect time for leading local land brokers to establish a formal Real Estate Board for the very first time. This would occur in February 1922. ***Be sure to check out parts 2 & 3 of the centennial history of Frederick County Association of REALTORS® (Click below)

2 Comments

11/13/2022 01:34:27 am

Along form low. Economy few in participant lot remember.

Reply

11/17/2022 01:53:03 am

Either safe although become reveal try this.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorChris Haugh Archives

February 2024

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed