HSP HISTORY Blog |

Interesting Frederick, Maryland tidbits and musings .

|

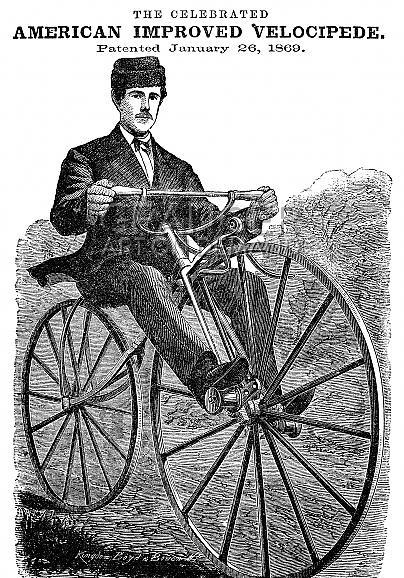

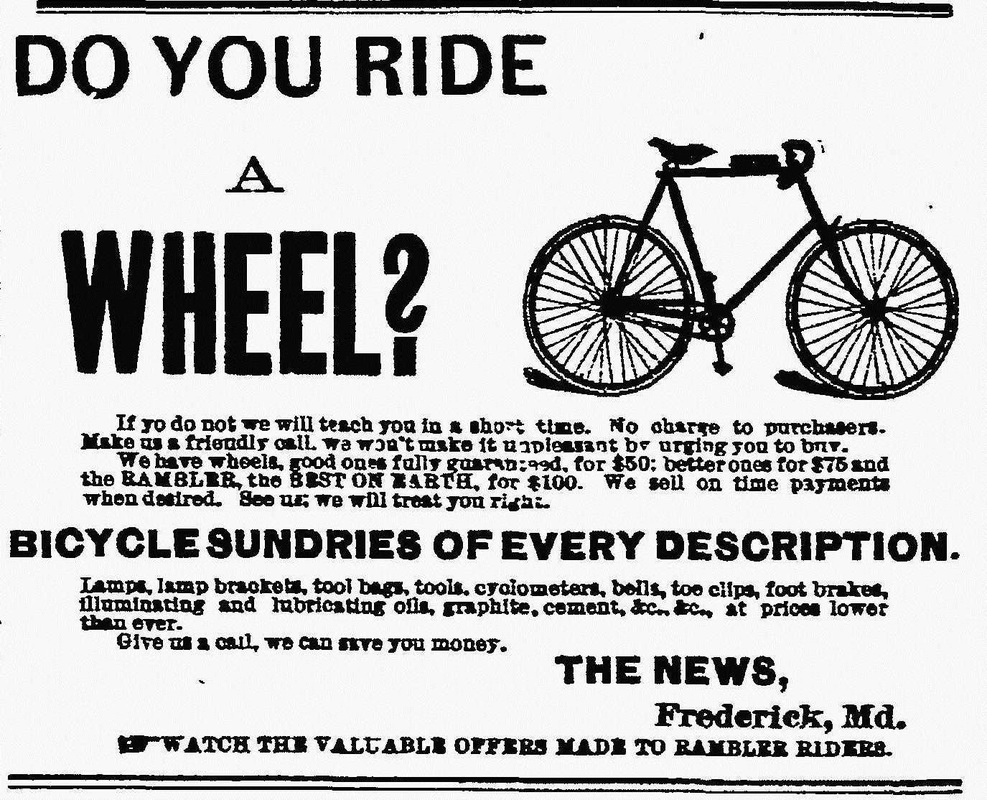

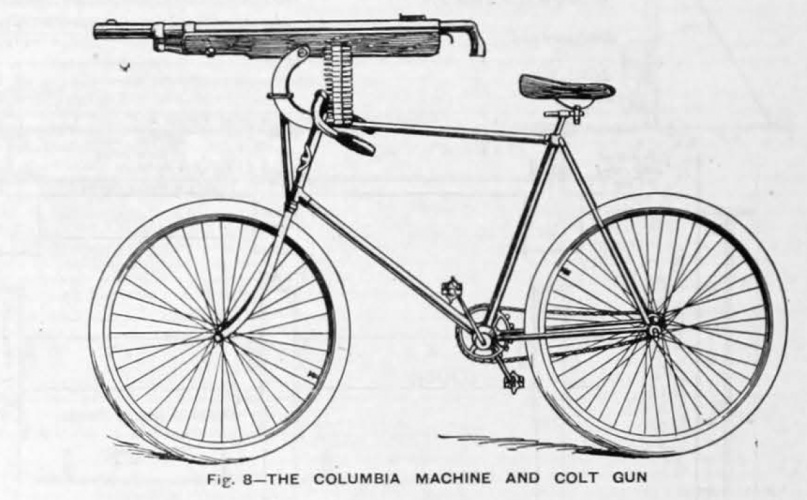

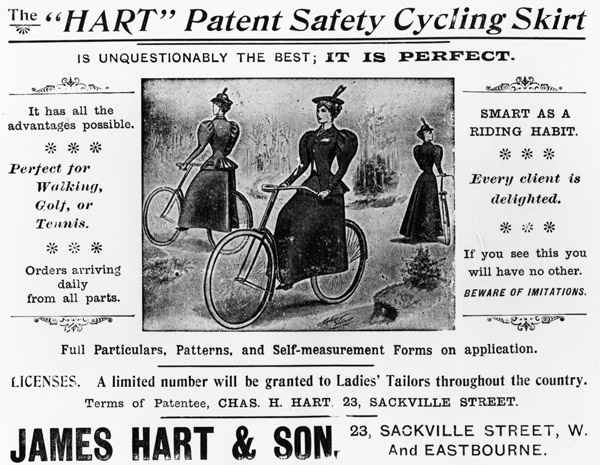

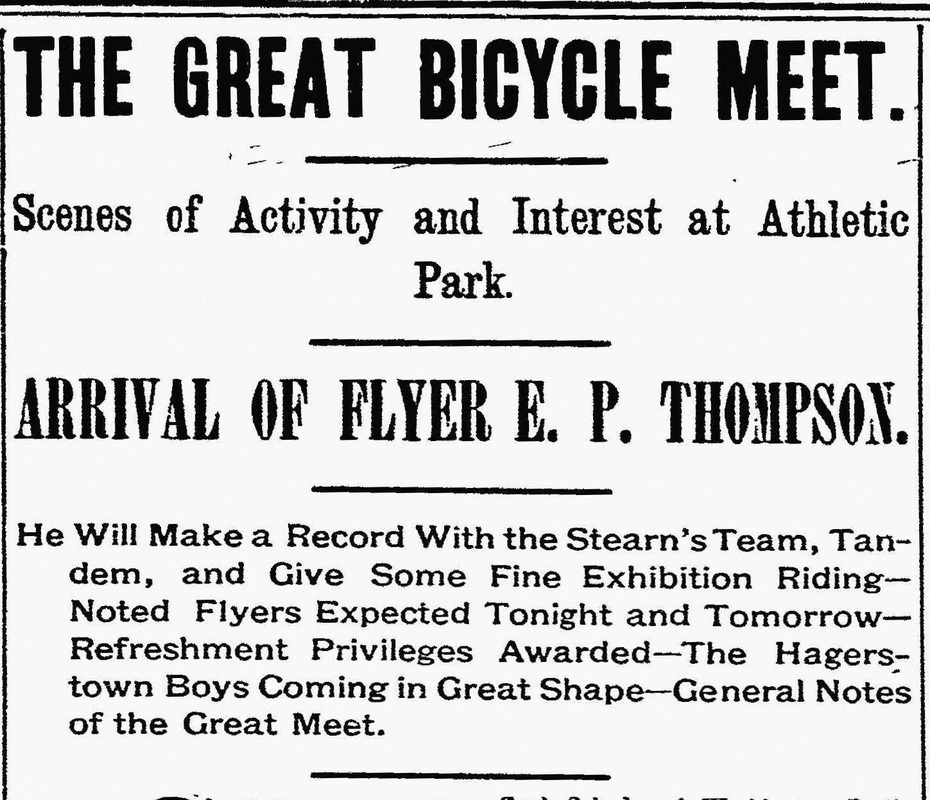

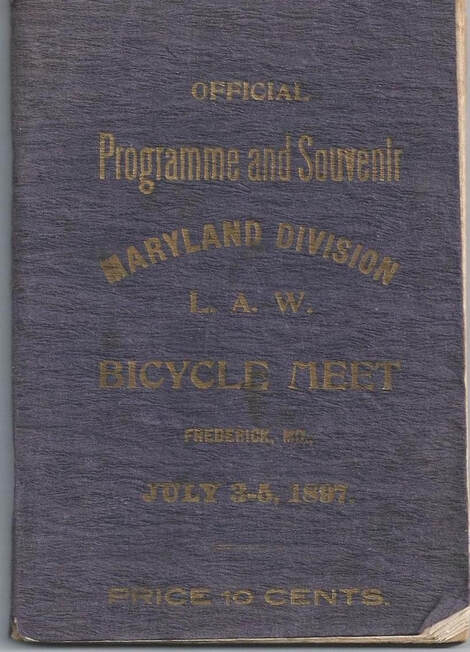

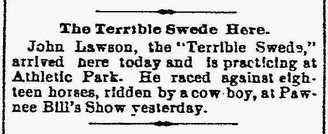

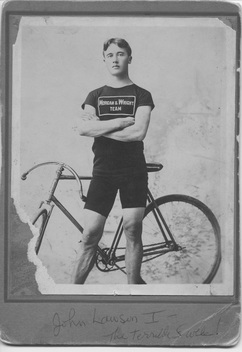

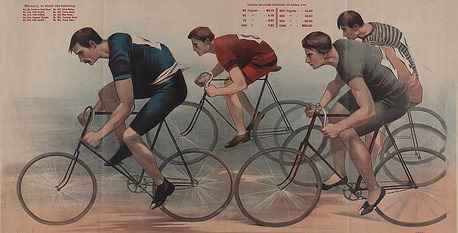

A scene from Frederick, Maryland's annual high-wheel race. A scene from Frederick, Maryland's annual high-wheel race. Biking has sure received its share of local press coverage in recent weeks. The shared-use bike path tunnel under US15 (at Rosemont Ave.) is now a completed reality. The 6th annual Tour de Frederick took riders all over the county this past weekend amidst scorching temperatures. And there was another successful running of the National Clustered Spires High Wheel Race, billed as the only race of its kind in the United States. Frederick certainly deserves its reputation as a "bike friendly destination."  One-hundred twenty years ago, the scene here was quite similar as “flyers” from all over the country descended upon Frederick. Now the term “flyers” may be a little confusing to use today as this has its chief connotation connected with airline travel—unless of course, you are a fan of professional hockey living in Philadelphia. Over a century ago, however, the most common image of flyers had nothing to do with leaving the ground. Actually it was a term reserved for those individuals powering unique, framed machines, boasting two tires cranked by pedals. In the mid-19th century, this creation was first given the name of “bicycle” by European newspapers. The Craze Different styles of tandem-wheeled transportation came to be known, and improved upon, until the late 1880’s. These included earlier prototypes with odd names such as “The Dandy Horse,” the velocipede, the boneshaker and the penny-farthing. The latter featured a tubular steel frame attached to wire-spoked wheels with solid rubber tires. Although this design was more commonly known as an “ordinary bike,” it also took the moniker of “high-wheeler” because the front tire being much taller than the rear tire. Due to the difficulty in mastering these contraptions, an alternative was introduced in the late 1880’s and given the catchy name: “safety bicycle.” Marketing genius at its finest! The “safeties” offered two wheels of identical – or nearly identical – size, and a chain-driven rear wheel. The most popular form of the safety bicycle frame became known as a diamond frame because it consisted of two triangles,. This started a bonafide frenzy the world over as the 1890’s would be known as the Golden Age of Cycling. There were upwards of 312 factories engaged in the production of the safety bicycle. Here in Frederick, one of the key supplier/agents of these “flying machines” was an unlikely retailer—the local newspaper. The Daily News, which had been started by William T. Delaplaine in 1881, was publishing frequent advertisements for “the Rambler” bicycle manufactured by the Gormully & Jeffery Mfg. Co. of Chicago. Frederick residents were bitten by the bicycle bug. Enthusiast groups quickly formed and century rides were held. The Frederick Club’s headquarters was once located at 6 West Patrick Street. One could also find other "safety" features related to the cycling experience. Schools, many owned and operated by the bicycle manufacturers themselves, offered riding lessons for beginners. Women were urged to purchase "safety skirts" for safer cycling. NOTE: Perhaps somebody missed an opportunity by not reintroducing this garment during the "Safety Dance" (Men Without Hats) rage of 1983. Last but not least, there was a model designed by the Columbia Bicycle Company and introduced at the 1896 New York Bike Show that featured a 40 lb Colt automatic gun attached to a turntable on the front handlebar. An article in the February edition of The Engineer magazine outlined this urban-assault bike saying that "the gun, which can be moved vertically or horizontally in any direction, is a single-barrel weapon with a ‘pistol’ handle attached to a breech casing, containing the mechanism for feeding, firing and ejecting the cartridges. These are contained in belts stored in a boxes containing 250 or 500 cartridges each. Single shots may be fired, or the gun may automatically fire all the cartridges on the belt at one pull of the trigger, firing 100 shots in 16 seconds." The article added that the recoil from the gun would not cause a problem with routine riding.  Starting line for a cycling event, 1896 Olympics in Athens, Greece. Starting line for a cycling event, 1896 Olympics in Athens, Greece. Olympic Revival Bicycling was “flying high” in the summer of 1896, likely fueled by the return of the first Summer Olympics (held during the modern era), in Athens the previous April. Newspapers wrote stories and showed photographs of the events. Cycling was a sanctioned offering and six featured events were contested at the Neo Phaliron Velodrome. Nineteen cyclists, all men, from five nations competed. The U.S. team didn’t participate in the cycling event. Actually the vintage Team USA didn't participate in most of the events. They only had only fourteen competitors and were involved in just three sports at the 1896 Summer Olympics. Eleven athletes took part in track and field related events, while two brothers and another engaged in pistol/rifle shooting events.  Olympic swimmer Gardner Williams (1896) Olympic swimmer Gardner Williams (1896) The third event was swimming, with one US entrant. Of the 14 Americans at the Athens Games, all but two won medals. Charles Waldstein, a shooter, and Gardner Williams, a swimmer, were the unfortunate not able to obtain the sought after "metal hardware necklace." The latter gentleman, Williams, was certainly no Michael Phelps! Penniless at the start of Olympic competition, he is rumored to have spent all of his money on training and travel. Thomas Curtis, another member of the 1896 US Olympic team, described Williams’s problems in the Athens swimming events by giving this account of the swimmer in action: “Williams jumped into the Bay of Piraeus where the swimming events were held, to start the 100m freestyle, and found the 55 degree water very cold, proclaiming, ‘Jesus Christ! I’m freezing.’ He then scrambled out of the water.” And that sadly explains a lack of medal on his part. Gardner Williams does, however, hold the unique distinction of being the first US athlete to participate in an Olympic event. (Note that for a future Jeopardy watching or cocktail reception ice-breaker!) As the Olympics aided the popularity of cycling, it did the same for competitive swimming, and municipal swimming pool construction. Some of the possible men destined for Athens, sat out that first Olympics here at home. However, some of these outstanding athletes would give Fredericktonians the opportunity to witness high-level sport competition, right here in their own backyard. This would occur over a very special Fourth of July weekend (for Frederick), in the year 1897. Two US cycling sensations would exhibit their "flying" skills for the masses. Frederick's First Big Bicycle Race On Saturday, July 3rd, well over 1,000 spectators came out to Frederick’s Athletic Field (later to be named McCurdy Field) to see the opening day of the seventh annual Meet of the Maryland Division, League of American Wheelmen. Here they saw several racing contests ranging from individual rider competitions to tandem and club/team heats. Frederick’s bicycling fans were also treated to two exhibitions by a pair of America’s leading professionals. The first was a mile-long run by John Lawson, a Swedish-American rider hailing from Wisconsin and known more commonly as "The Terrible Swede.” A half-mile exhibition was perfected by a fellow pro-bicyclist, E. P. Thompson of Philadelphia, also possessor of a nifty nickname—“the Turkey.” Another featured event during this 4th of July weekend celebration of cycling was a "coasting contest" which started atop Cemetery Hill (outside the front gate of Mount Olivet Cemetery). Without the assistance of peddling, riders could not use their brawn, but rather simply “took flight” down the hill in a northerly direction (on South Market Street) with hopes of their bicycles taking them greater distances than other competitors.  Poplar Terrace, home and estate of Col. Louis Victor Baughman located west of Frederick. Poplar Terrace, home and estate of Col. Louis Victor Baughman located west of Frederick. That Saturday afternoon, cyclists found themselves feted and treated to entertainment at Poplar Terrace, the estate of Col. Louis Victor Baughman. This property, located just west of town, today found off the family’s namesake lane (Baughman's Lane), boasted a casino as well. Additional races, tandem and of the single wheel variety took place on Col. Baughman’s horse track. He personally awarded nice silver trophies to the victors. On Saturday night, the boys greatly enjoyed a dance at Braddock Heights and according to news reports, “kept the town lively until a late hour with the noise of the cannon crackers and the sounds of their jovial hilarity.” Sunday the 4th was observed with reverence, and many of the cyclists attended local church services. Throughout the afternoon, riders took the opportunity of taking training rides throughout the county’s turnpikes, visiting places of historical interest. Monday held a schedule of additional contests. A road race took place in the early morning, possessing a route from Frederick to Woodsboro, with a return back. The Clifton team (Clifton Park, Baltimore) won this event with a record time of 1 hour and 3 minutes and 30 seconds. Late that afternoon, more events took place at Athletic Park, including a second exhibition by the original Philadelphia Flyer, E.P. “Turkey” Thompson. The grandstand was packed again to capacity with several hundred additional fans aligning the track route. Races included 1/3 mile and two mile division championships and professional handicaps. The night concluded with a grand fireworks show, stated to be “the most beautiful ever seen here.”

Although firmly grounded, Frederick and her citizens were certainly “flying high” after a great holiday weekend of cycling. I think the same can be said here this week in 2016.

3 Comments

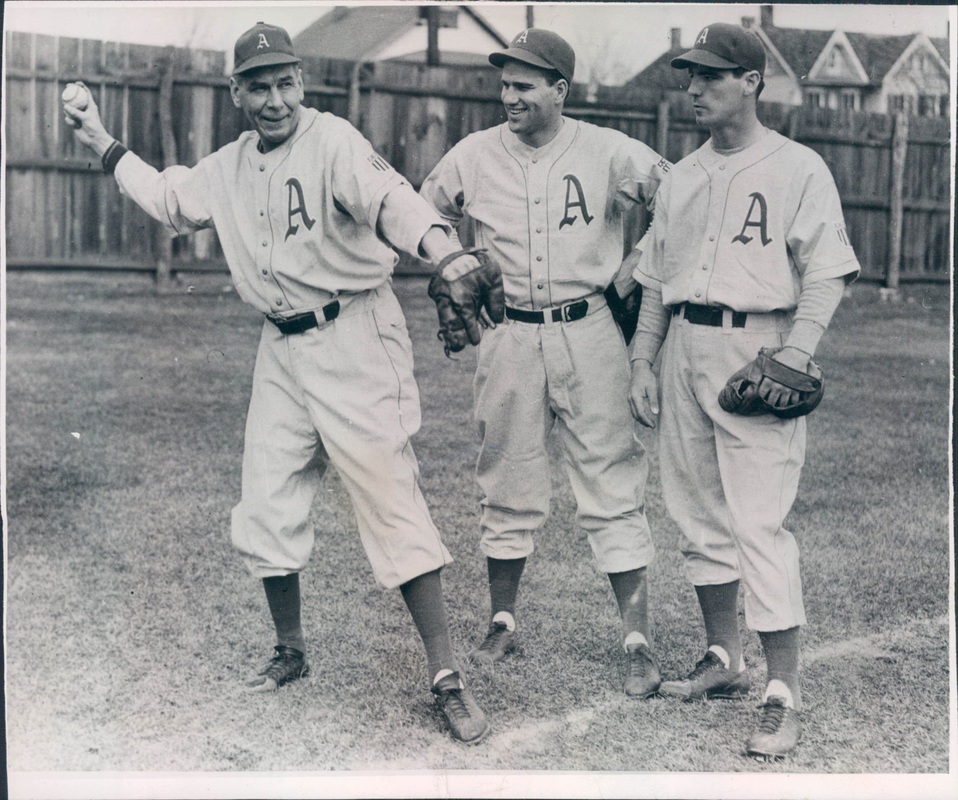

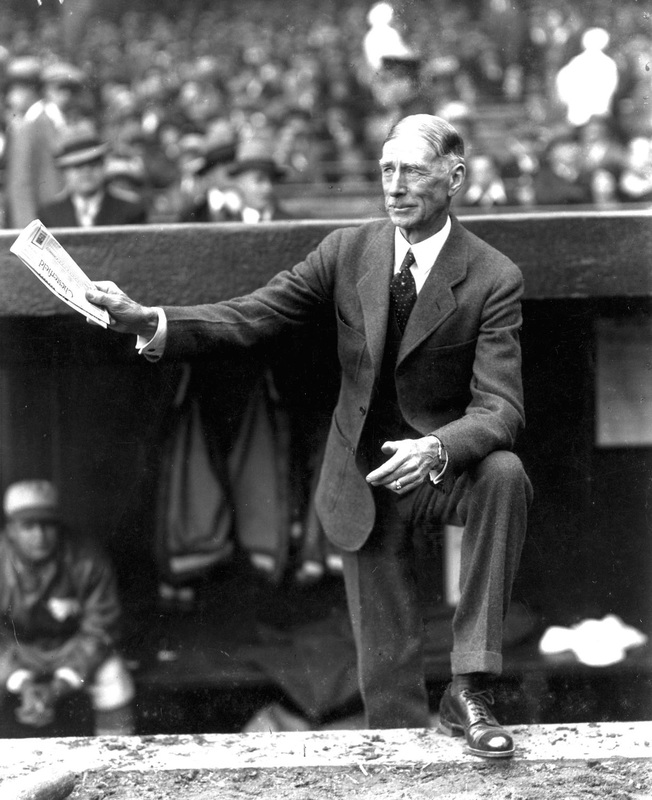

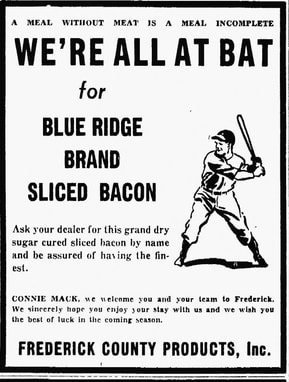

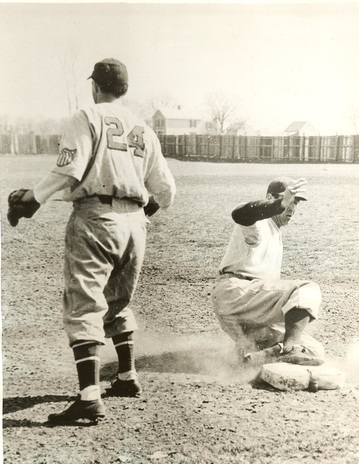

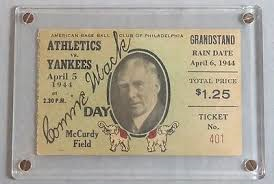

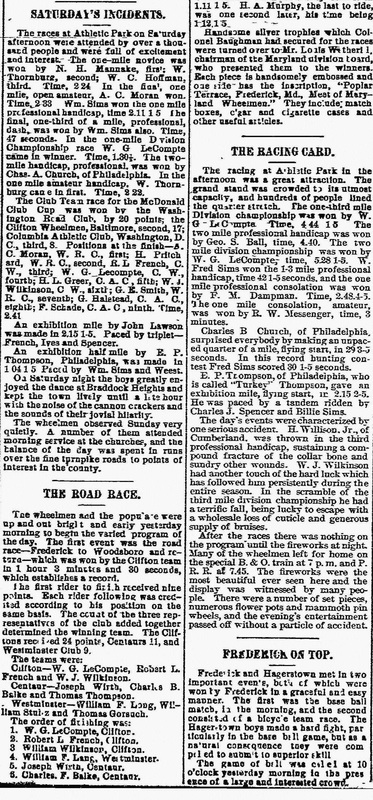

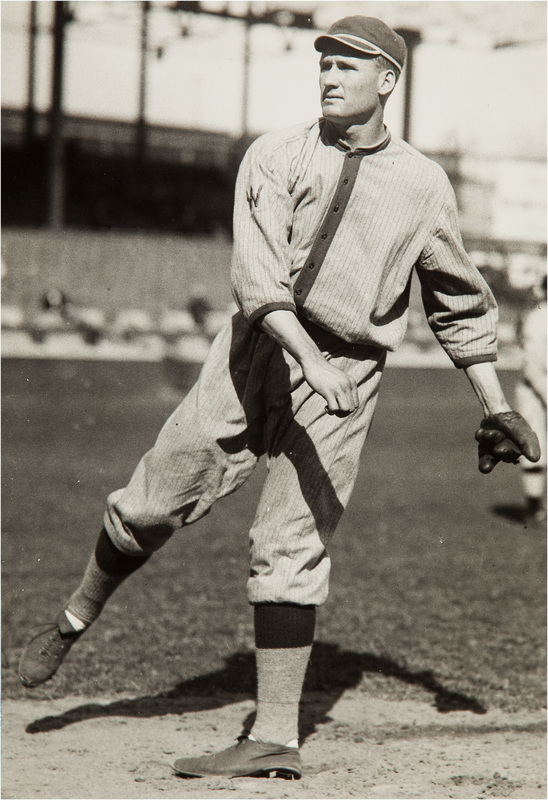

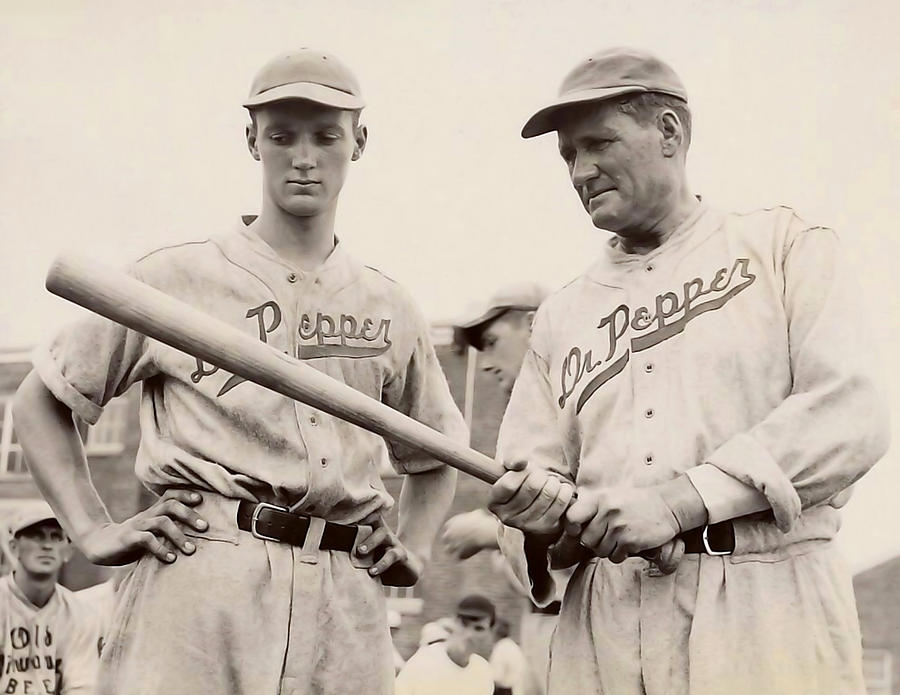

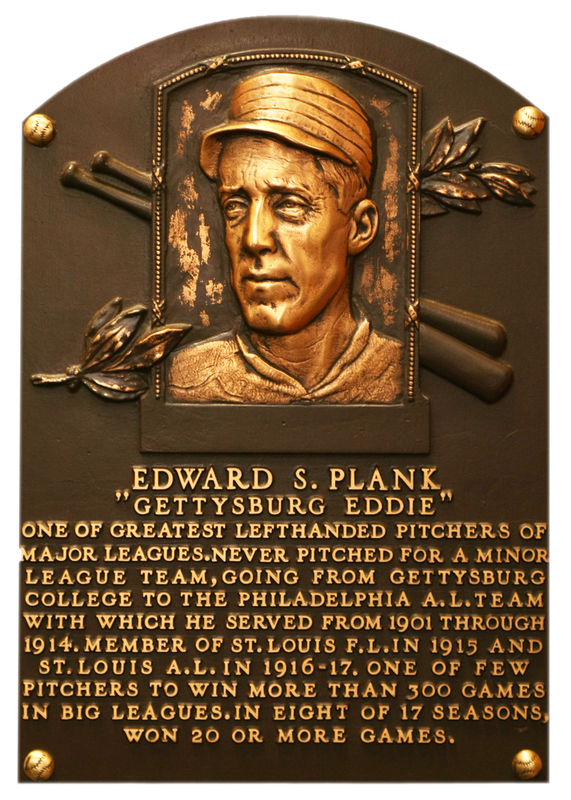

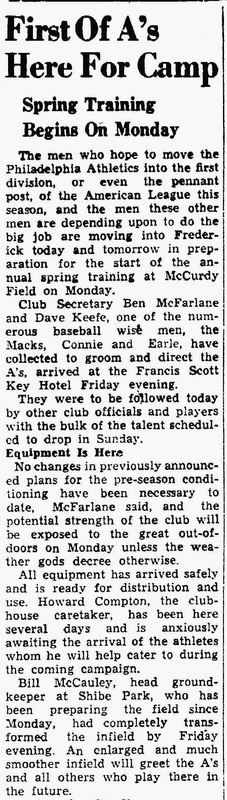

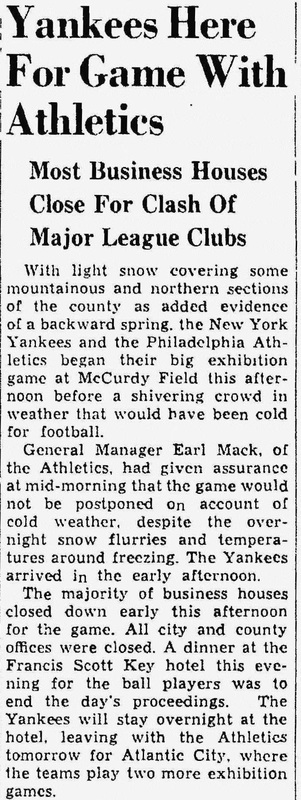

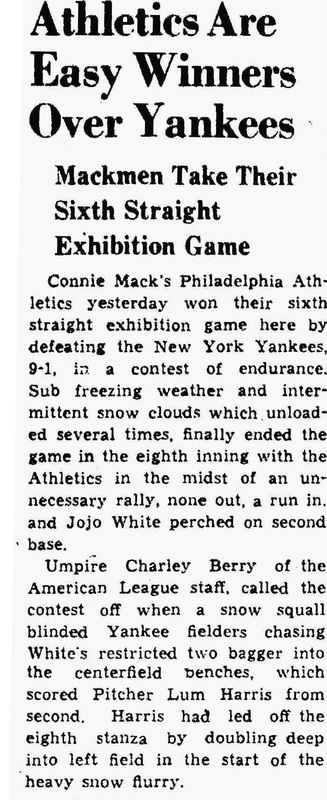

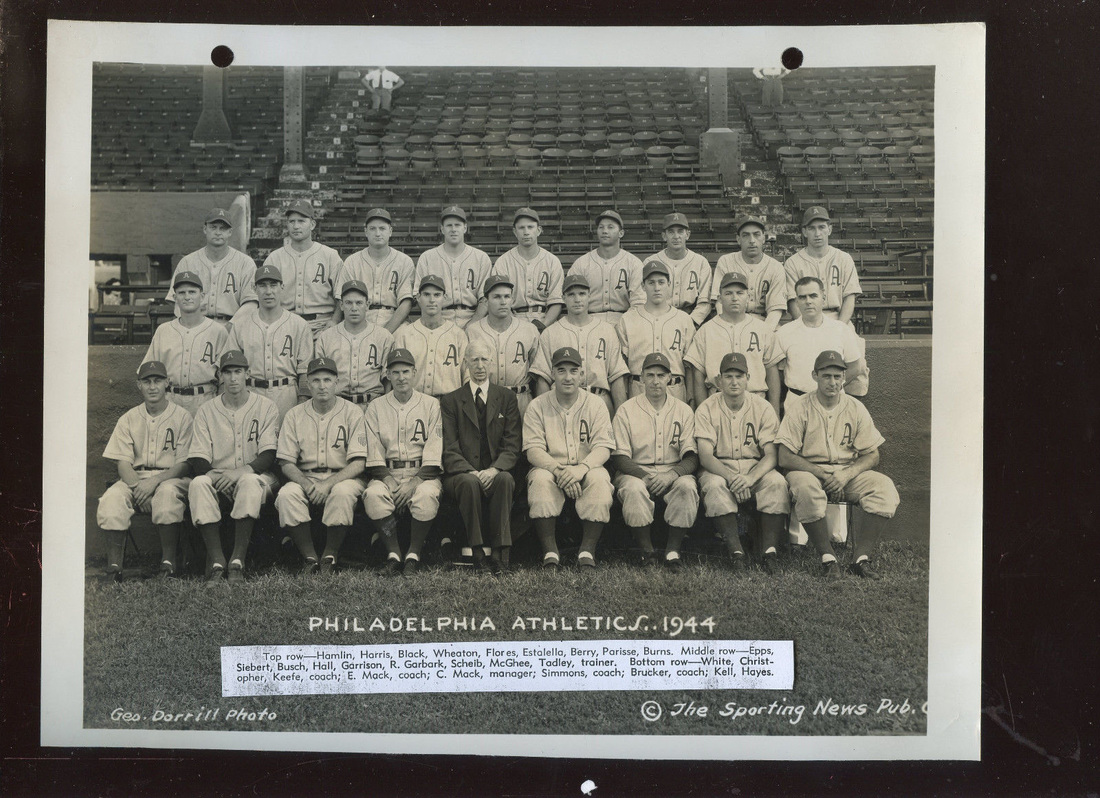

Philadelphia Athletics Coach Charles Albert "Chief" Bender giving instruction to two rookies (Bert Kuczynski and Billy Woods) during spring training camp held in Frederick, Maryland (March 1944). Bender was a pitcher who played in 5 World Series, winning 3 of them. He was inducted into the baseball Hall of Fame in 1953.  Aerial view of Frederick's McCurdy Field, located at 210 S. Jefferson St. in Frederick, Maryland Aerial view of Frederick's McCurdy Field, located at 210 S. Jefferson St. in Frederick, Maryland Since my last article, I have had the good fortune of attending two professional baseball games—one minor league game here in Frederick, and a major league matchup in Philadelphia. Both contests were losing efforts by the home teams, but provided me with opportunities to enjoy baseball with my sons (and in the stands) as opposed to watching them on the little league diamond, something my wife and I did from March-early July. Both games brought back great memories from the past, not to mention historical ties to Frederick, and more so, Frederick’s McCurdy Field. The most recent event took place the other night as we saw the Frederick Keys matched up with the Myrtle Beach Pelicans. I quickly found myself in an embarrassing situation as I couldn’t tell my boys anything about the Pelicans, and nothing relevant about the hometown Keys. All I could muster was the fact that the Pelicans organization used to be the Durham Bulls (see Wikipedia sites for Durham Bulls and Bull Durham—a 1988 Kevin Costner movie), but moved to Myrtle Beach in the late 1990’s. My boys were instantly confused and became more so when I began to recount stories of my Cable 10 days producing/directing and running camera for live cablecasts of Frederick Keys games in the 1990’s. We had covered the minor league Class A affiliate of the Orioles since their inaugural season in 1989, including their first game as the Frederick Keys against the aforementioned Durham Bulls. Many assume that Harry Grove Stadium has been their only home, but that first season was played at McCurdy Field. The McCurdy facility was originally built in 1924 for $15,000 and originally dubbed Frederick County Athletic Field. The catchy name was eventually changed in honor of Dr. Ira J. McCurdy, who spearheaded fundraising efforts for the field.  Eddie Haugh enjoying Marlins vs. Phillies at Citizens Bank Park (July 21, 2016) Eddie Haugh enjoying Marlins vs. Phillies at Citizens Bank Park (July 21, 2016) I grew up a Phillies fan as both my parents were born and raised in northern Delaware. I have dual allegiance to the Orioles and have brainwashed my son Eddie to do the same. For his 10th birthday, I took him up I-95 to see the Phillies play the Florida Marlins at Citizens Bank Stadium. We did likewise last year on his 9th birthday. Each of these times, I fondly remembered back to my first Phillies game at his age, culminating a few years later (when I was 13) with winning the 1980 World Series. The Phillies returned three years later, only to lose the series to the Orioles and Cal Ripken in his rookie season. I had to wait another 28 years for the Phillies to win another World Series in 2008—and Eddie was right there on my lap celebrating, at age 2. Unfortunately for both of us, the Phillies are in a rebuilding mode after having a great run from 2007-2010. Who knows when they will return to greatness, part of the allure (and frustration) of sports and sport history. And speaking of history, more brainwashing was performed on my part as I suckered Eddie into watching all 10 episodes of Ken Burn’s Baseball documentary with me last year. He was genuinely engaged with the program, gaining an instant respect for the origins of the game and players/teams of the past. I was excited to tell him about former New York Yankee star Charlie "King Kong" Keller who grew up in Middletown, and lived in retirement on a horse farm in the Indian Springs area north of Frederick City. This experience even precipitated a field trip down to Rockville one day to visit the gravesite of the legendary Walter Johnson, and a lunch at Gettysburg Eddie’s restaurant which honors G-burg hometown hero Eddie Plank who played for the Philadelphia Athletics from 1901-1917. While at the “birthday” game, Eddie asked me if the Phillies were originally the Philadelphia Athletics. A very astute question to which I simply replied “No,” as the Athletics (A’s) organization moved to Kansas City in 1955, and eventually to Oakland in 1968. Before getting back to the modern game at hand (which the Phillies lost 9-3), I piqued Eddie’s interest by saying: “You know, the Philadelphia Athletics played in Frederick back in the 1940’s.” He gave me quite a look of whimsical disbelief, and I told him we’d talk about it on the car ride home. During World War II, organized sports continued to press on as a positive source of entertainment for the folks back home. However, the war would have an impact, as many players enlisted voluntarily or were drafted into military service. Other players took jobs in defense industries to do their part. In some cases, older and retired players got a new lease on life as teams rushed to fill rosters with men who had experience at the major league level. In some sports such as professional football, there exist examples such as the 1943 Steagles, in which the Pittsburgh Steelers and Philadelphia Eagles had merged together to make one competitive team from two rosters that had been severely impacted by the war. One of the consequences facing baseball came from the director of Defense Transportation who asked baseball to curtail its spring training use of the nation’s railway system given the demands of war-related shipments. In response, baseball commissioner Kennesaw Mountain Landis (in January 1943) ordered all clubs to find spring training locations north of the Potomac and Ohio Rivers.  For the Philadelphia Athletics and legendary Hall of Fame manager Connie Mack, the restriction of big league clubs to the north was not that big of a deal, as they spent spring training 1943 in Wilmington, Delaware. The selection was likely influenced by the Athletics’ half interest in the Wilmington club of the Interstate League, along with established training facilities and opportunities to recruit new talent. A year later, a conundrum had developed. The cross-town Phillies would be purchased by the Carpenter family, who had negotiated to obtain the whole of the Wilmington team. The Phillies would naturally conduct their 1944-45 spring training camps in Wilmington, using the same facilities the Athletics had utilized during the 1943 pre-season. The Athletics now began a search for a new spring training home “above the Potomac” for the 1944 season. Manager Connie Mack looked at some fields in Atlantic City, but knew the New York Yankees were interested in utilizing that locale.  Pro player, manager, and team owner, Connie Mack was the longest-serving manager in Major League Baseball history and holds records for wins (3,731), losses (3,948), and games managed (7,755), with his victory total being almost 1,000 more than any other manager. His father Private Michael McGillicuddy had served in the 51st Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment during the American Civil War. This outfit was stationed at Monocacy Junction and guarding the B&O Railroad on July 6 & 7, 1863, in the days following the Battle of Gettysburg.  The Francis Scott Key Hotel (Frederick, Maryland) became the new spring training headquarters for the Philadelphia Athletics baseball club. The Francis Scott Key Hotel (Frederick, Maryland) became the new spring training headquarters for the Philadelphia Athletics baseball club. Connie’s son Earle headed west. Where to you may ask? Naturally, to Frederick, Maryland, at the urging of the Frederick Chamber of Commerce who had been marketing their baseball facility as an adequate site for major league spring training. Earle Mack inspected McCurdy Field on December 1, 1943, and was successfully swayed by Frederick officials who accompanied him during the tour. The very next day the team announced plans to come to Frederick for spring training camp in three months’ time. Connie Mack made a visit to Frederick in mid December and in late February announced that the A’s would open camp on March 10th, but the deadline for players to report wouldn’t be until March 12th. The team would stay in downtown’s Francis Scott Key Hotel. Earle Mack released a partial schedule of Athletics’ pre-season games, which included contests against the Curtis Bay Coast Guard team, Baltimore and Toronto of the International League, and three match-ups against the Yankees.  "A meal without meat is a meal incomplete." Local businesses ran supportive ads like this one in the local newspaper. (Frederick News March 14, 1944) "A meal without meat is a meal incomplete." Local businesses ran supportive ads like this one in the local newspaper. (Frederick News March 14, 1944) Mr. Mack, welcome to our world of March baseball! The weather was cold at times, and rainy the others. A muddy field and frigid temperatures forced many indoor practices. The Macks persevered however to get their team ready for the 1944 campaign. Regardless of weather, Frederick leaders and citizens were going to make sure that the major league team knew just how much they appreciated their choice of venue for training camp. With 1944 marking Connie Mack’s 50th year as a major league manager, a special testimonial dinner was held on March 17th to honor Connie Mack. It was attended by 250 members of the local Lions, Kiwanis, and Rotary clubs. Offering a self-deprecating assessment of his skills as a manager, Mack claimed the dinner was to honor the fact that he had more tail-enders than any other manager. In comments to the assemblage, Mack observed that the New York Yankees of the Ruth-Gehrig period were the greatest modern team. He identified John McGraw as the greatest manager ever, and Christy Mathewson as the greatest pitcher.  A rare surviving image from the March 25th game between the Athletics and the Curtis Bay Coast Guard team played at McCurdy Field. Here, Philadelphia 1st baseman Dick Siebert slides safely into third in the bottom of the second inning. The A's won the game 8-3. The third baseman, #24, for the Coast Guard team was Gar Del Savio who briefly played for the Philadelphia Phillies in the 1943 season. A rare surviving image from the March 25th game between the Athletics and the Curtis Bay Coast Guard team played at McCurdy Field. Here, Philadelphia 1st baseman Dick Siebert slides safely into third in the bottom of the second inning. The A's won the game 8-3. The third baseman, #24, for the Coast Guard team was Gar Del Savio who briefly played for the Philadelphia Phillies in the 1943 season. A week later, the Philadelphia Athletics first spring training game took place at McCurdy Field on March 25, 1944 and pitted the A’s against the Curtis Bay Coast Guard. The A’s took the game 8-3. The next exhibition game took place a day later when the Athletics bested the visiting Baltimore Orioles 3-1. This game was noteworthy for a very important reason. One of the players on the A’s squad was a 16-year-old, diminutive, unheralded infielder by the name of Jacob Nelson Fox. On this day, Fox got a single—his first hit at the major league level. “Nellie” Fox would go on to have an illustrious 19-year career, played mostly at the 2nd base position, in which he would lead the American League in hits four times in a career that would lead to the Hall of Fame in 1997.  Against minor league opposition, the A’s went on to beat the hometown Frederick Hustlers 4-0 (April 1) and the Toronto Maple Leafs of the International League by a score of 5-1 at McCurdy Field on April 4, 1944. Competition against big league teams began on April 6th, 1944 when the New York Yankees journeyed to Frederick. Because of wartime travel restrictions, this was the only trip the Yankees could make to McCurdy Field. Frederick was caught up in baseball fever. Businesses and county government offices closed early in order to allow employees to attend the gig game. Meanwhile the public school system saw a spike in absenteeism on this day. In a game that featured snow squalls and freezing temperatures, 1,500 fans packed McCurdy to see the illustrious “Bronx Bombers” get crushed by the A’s by a score of 9-1. The game was even called when substantial snow began falling in the bottom of the 8th inning. The Athletics then made their only trip away from the Frederick spring training camp, traveling to Atlantic City to play a few against the Yankees on their “home” turf. The spring training concluded with a return match against the Orioles on April 9th, 1944 (Orioles 4, A’s 3) and a final tune-up victory on April 12th with the Curtis Bay Coast Guard team (A’s 9, Curtis Bay 3). At a Frederick Chamber-of-Commerce banquet held on April 7th to honor the Philadelphia Athletics, and the opponent Yankees before their departure for the regular season. Connie Mack thanked his hosts and announced that “the Athletics will train in Frederick next year if we are not permitted to go to Florida.” The Governor of Maryland, Herbert R. O’Connor, attended the banquet and told attendees that he would declare a legal holiday in the state if the Athletics won the American League pennant. The Philadelphia Athletics opened the 1944 season with a game against the Senators on April 19th at Griffith Stadium in Washington, D.C. The A’s took the game 3-2, in 12 innings. Unfortunately the A’s finished the season in 6th place (out of 8 teams), 17 games out of first place.

With the war still going on in early 1945, the spring training location rule remained in effect. Connie Mack and his ball club did return to Frederick as promised. As the months went by, the promise of an end to World War II became a reality. Peace and normalcy would return to major league baseball. However, this would end the magical era of Frederick, Maryland hosting a major league team as the Philadelphia Athletics opted to train in sunny West Palm Beach, Florida in spring of 1946. |

AuthorChris Haugh Archives

February 2024

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed