HSP HISTORY Blog |

Interesting Frederick, Maryland tidbits and musings .

|

|

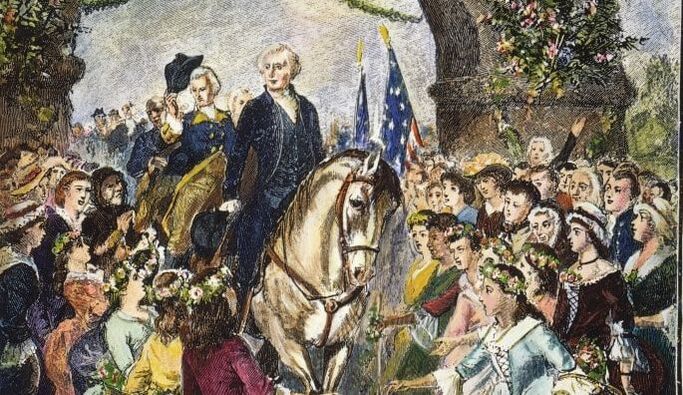

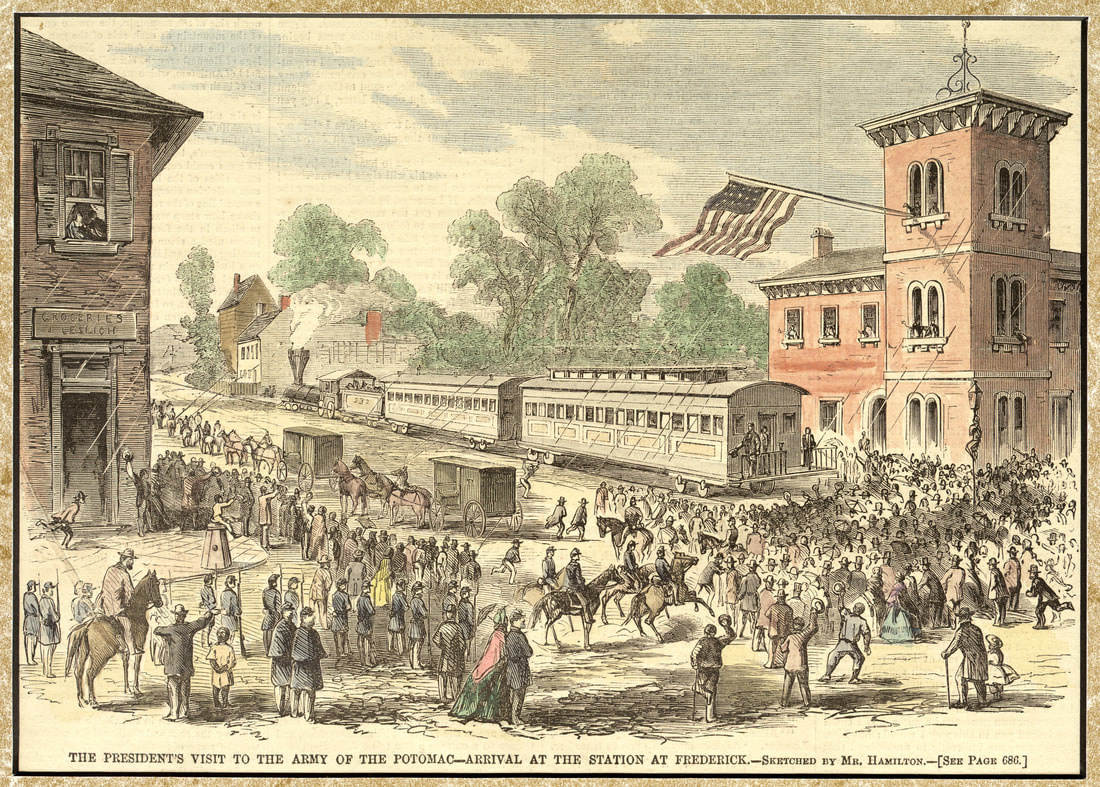

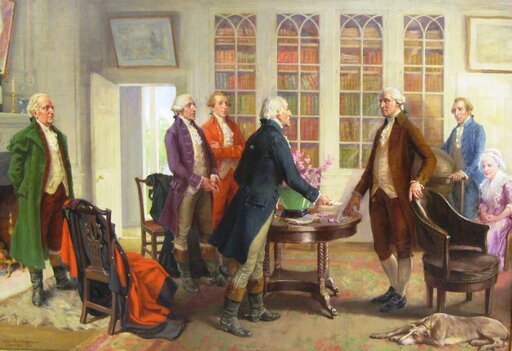

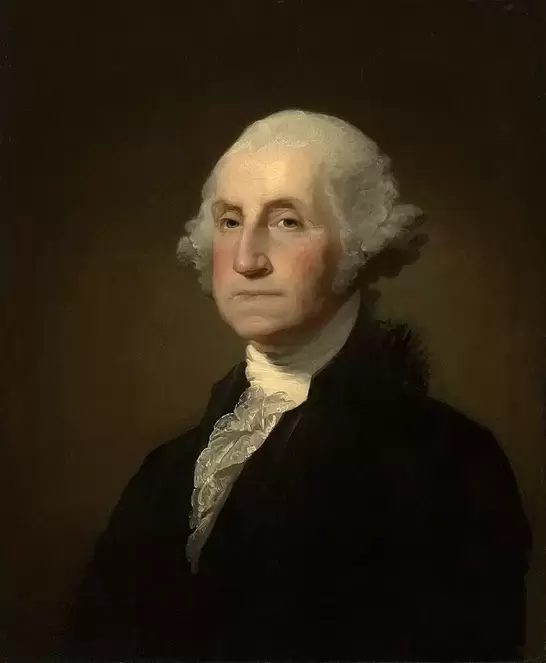

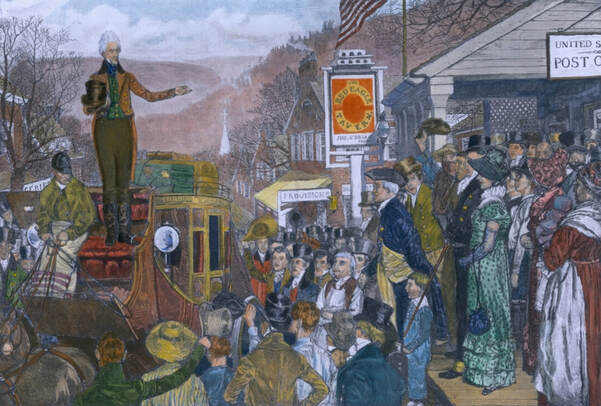

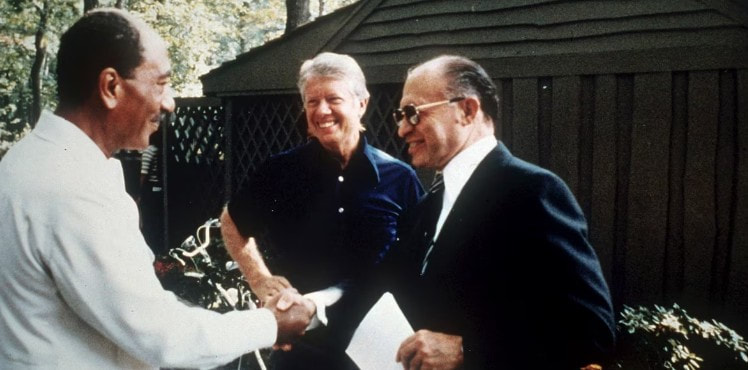

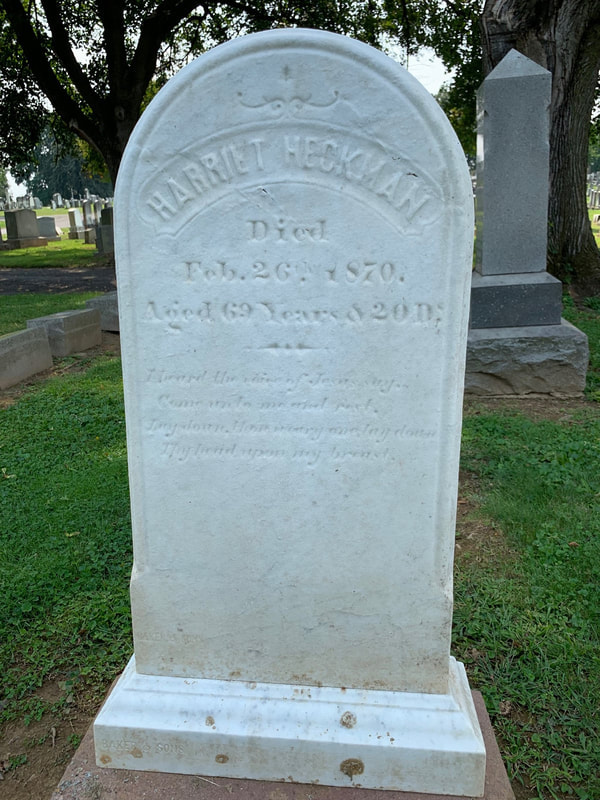

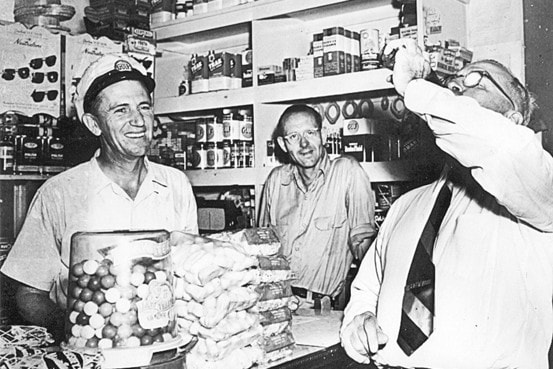

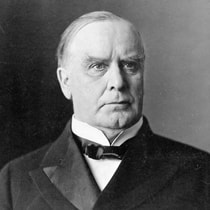

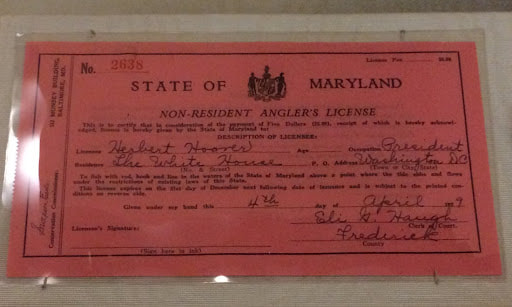

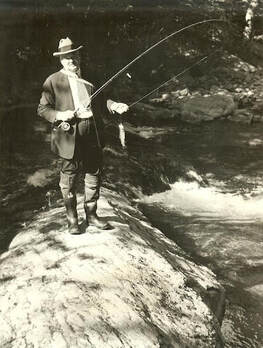

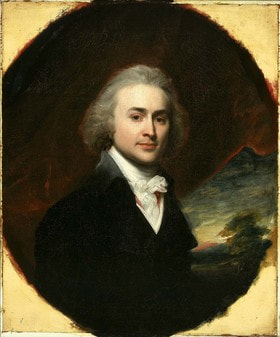

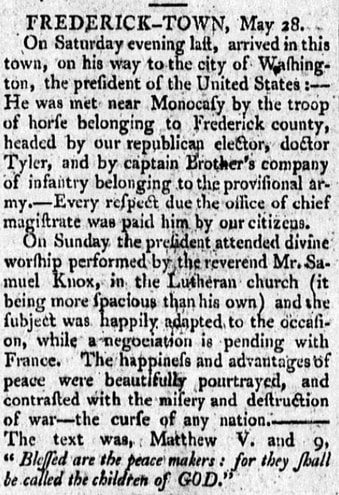

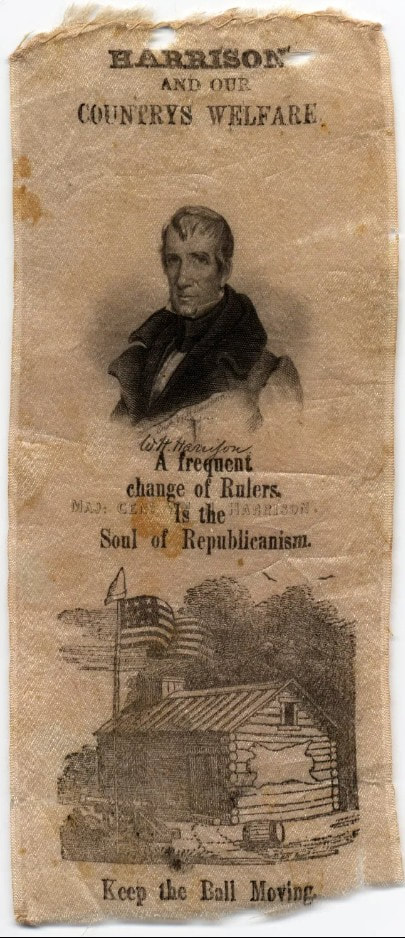

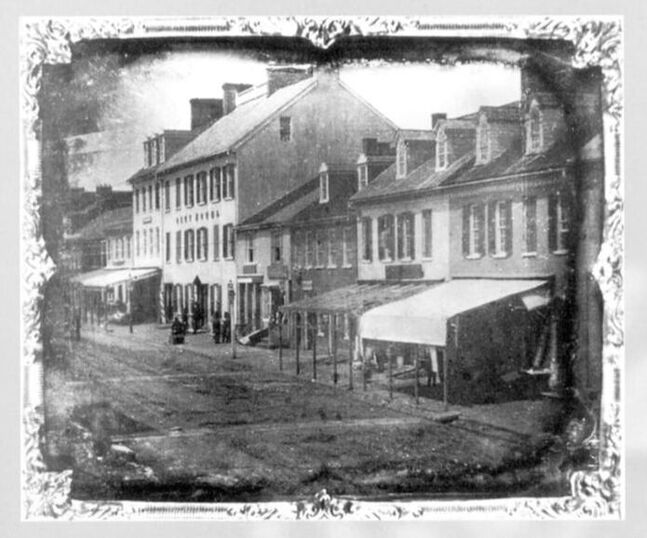

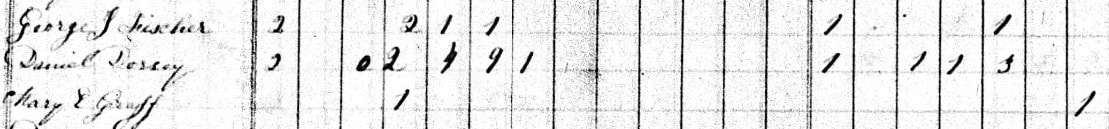

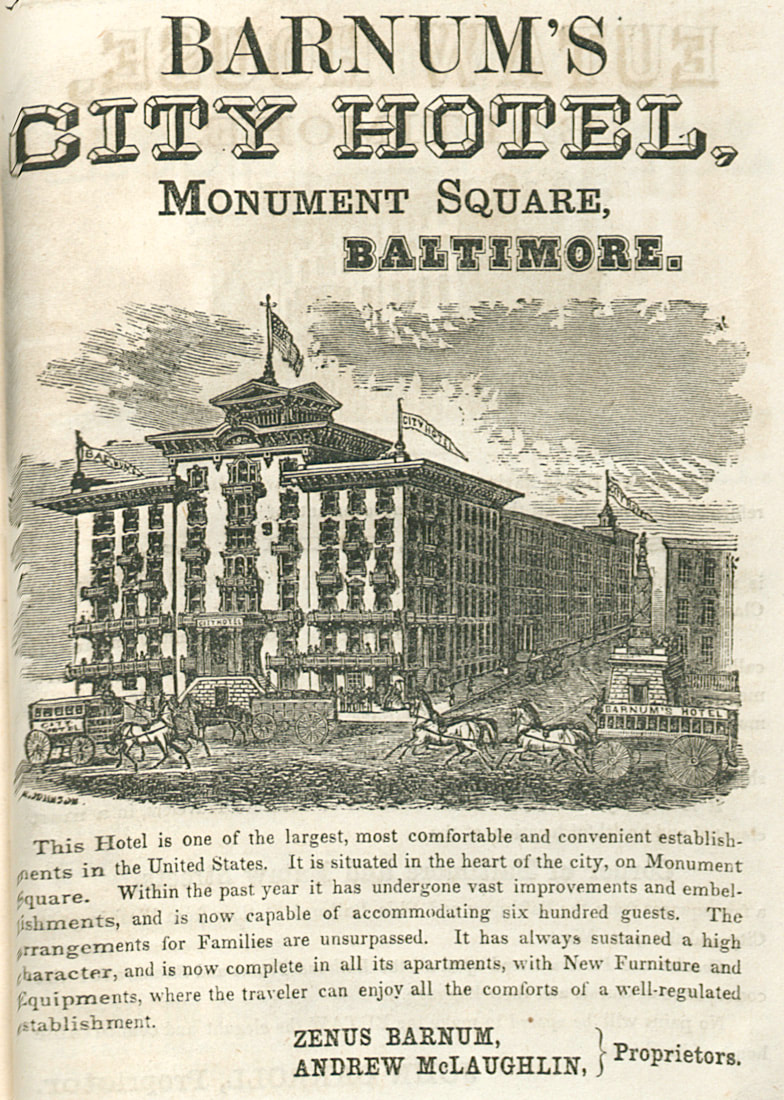

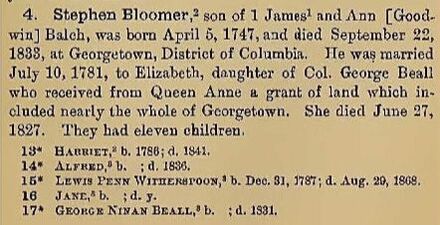

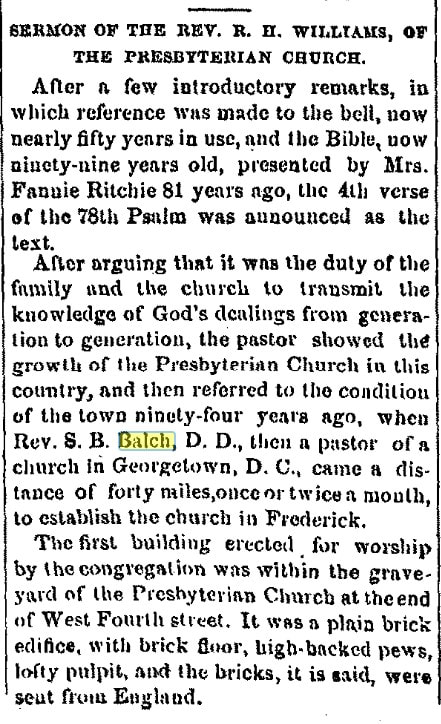

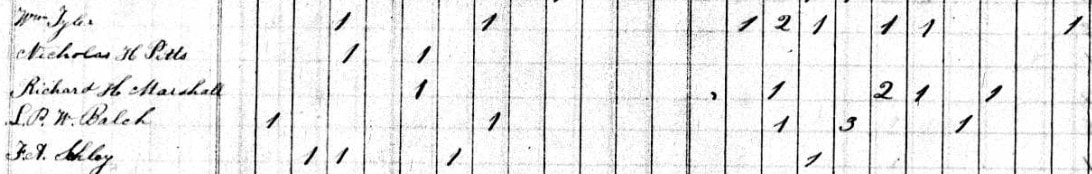

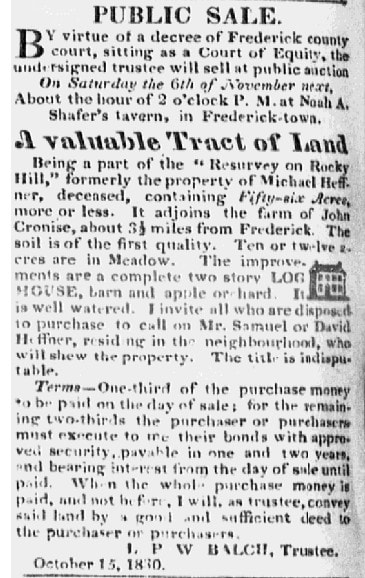

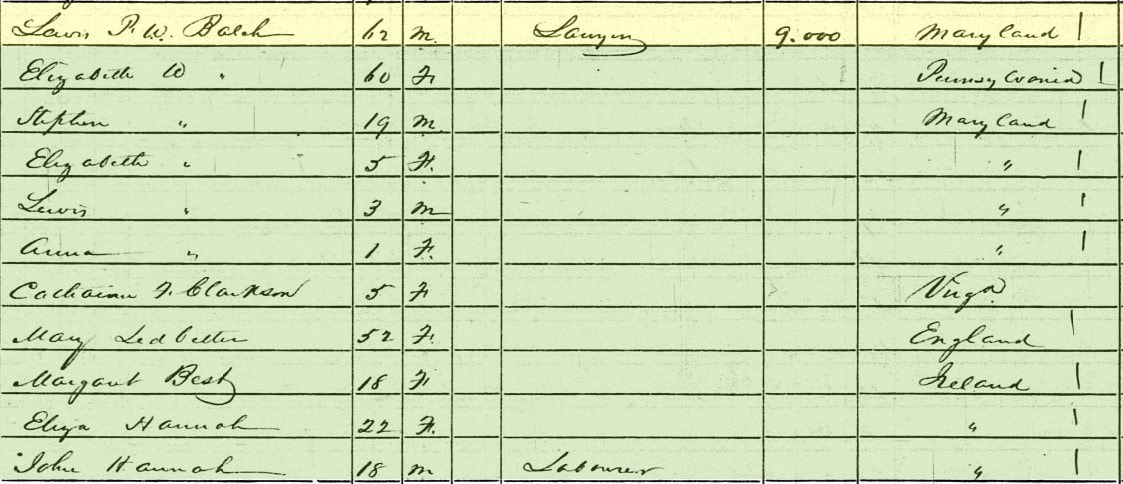

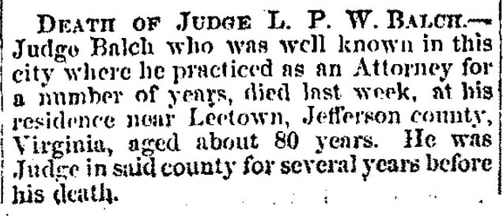

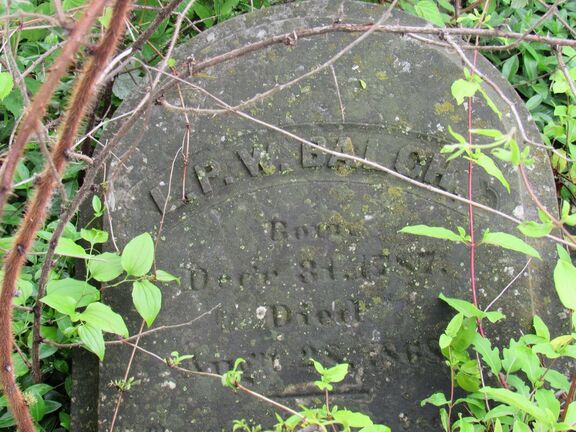

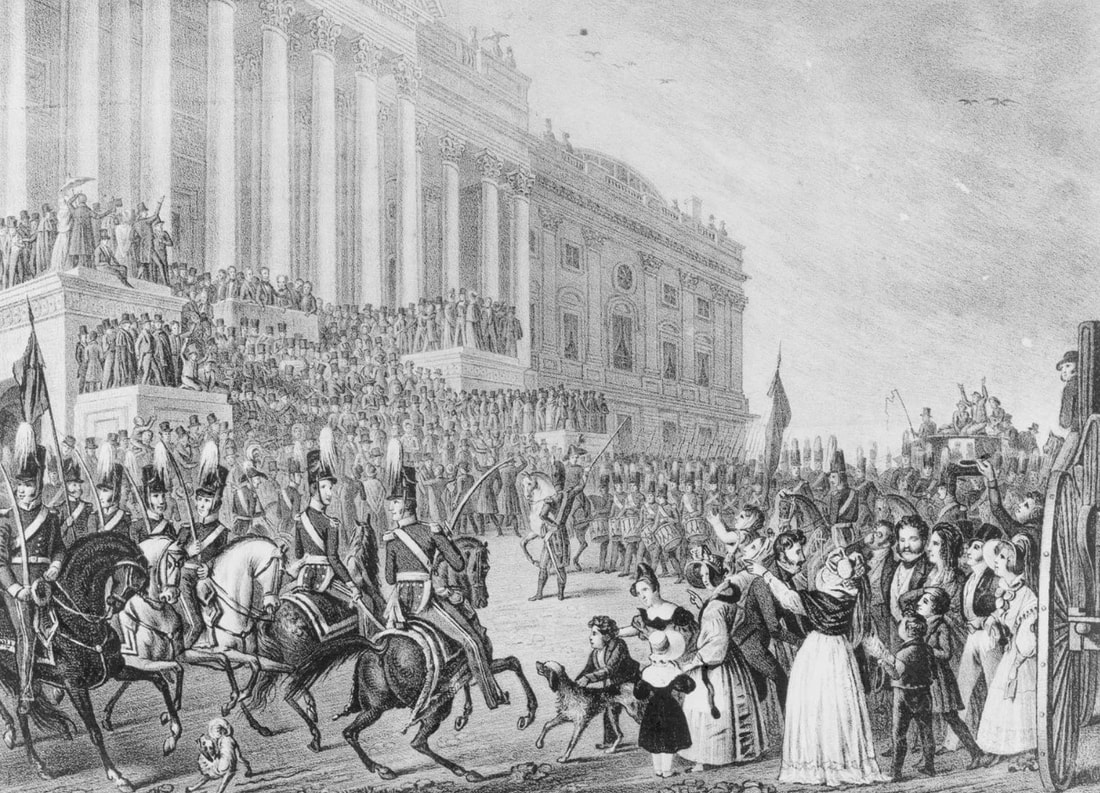

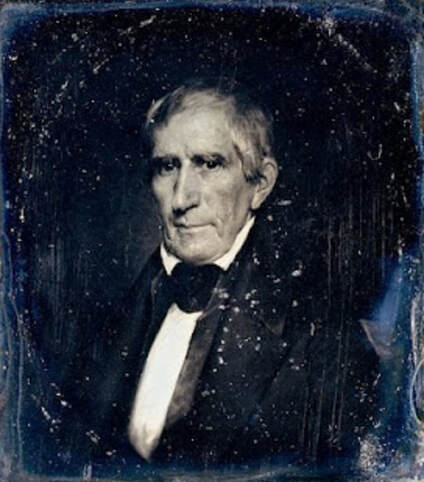

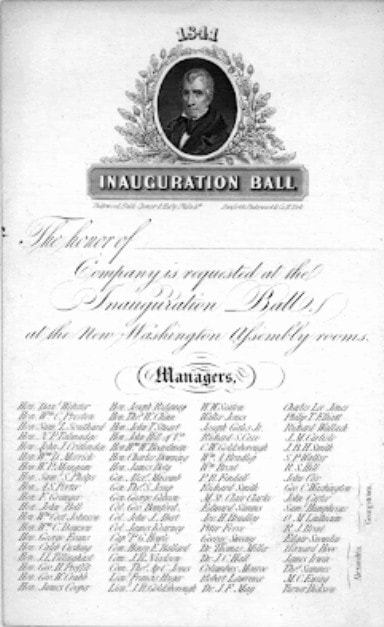

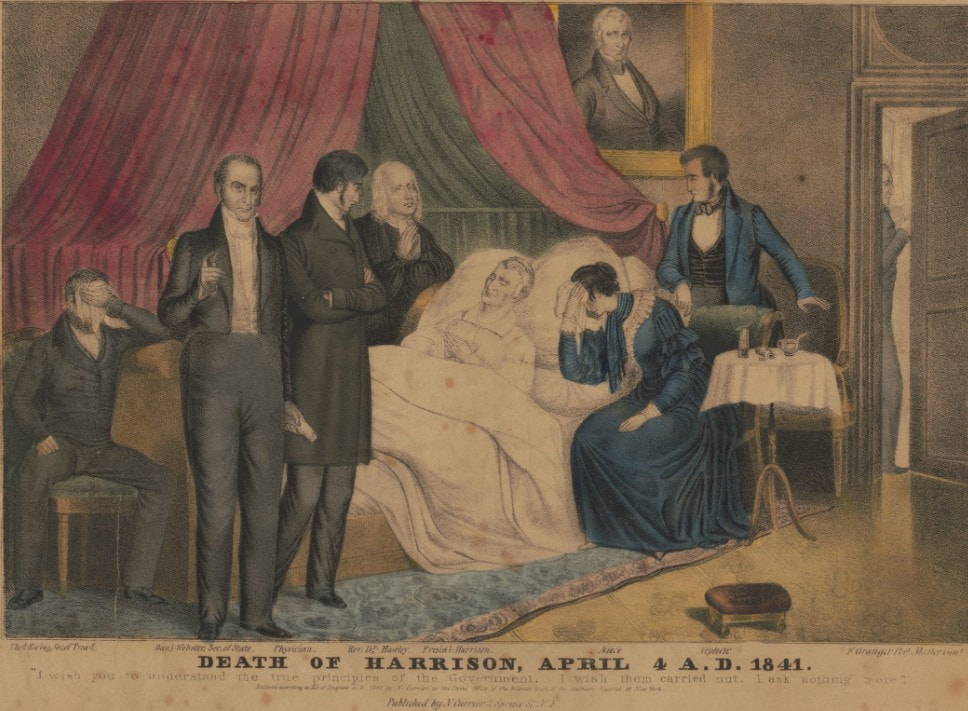

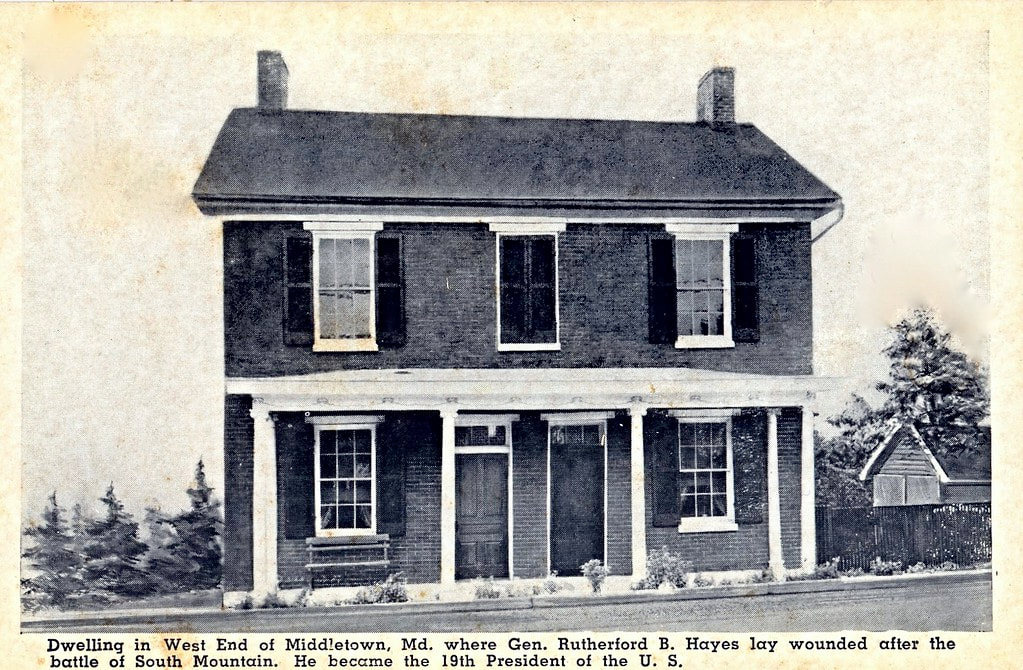

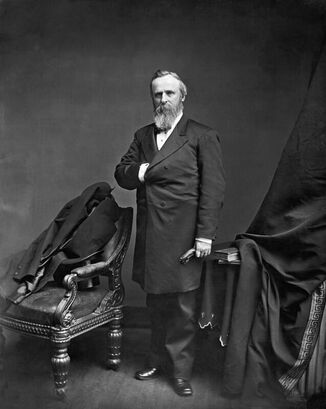

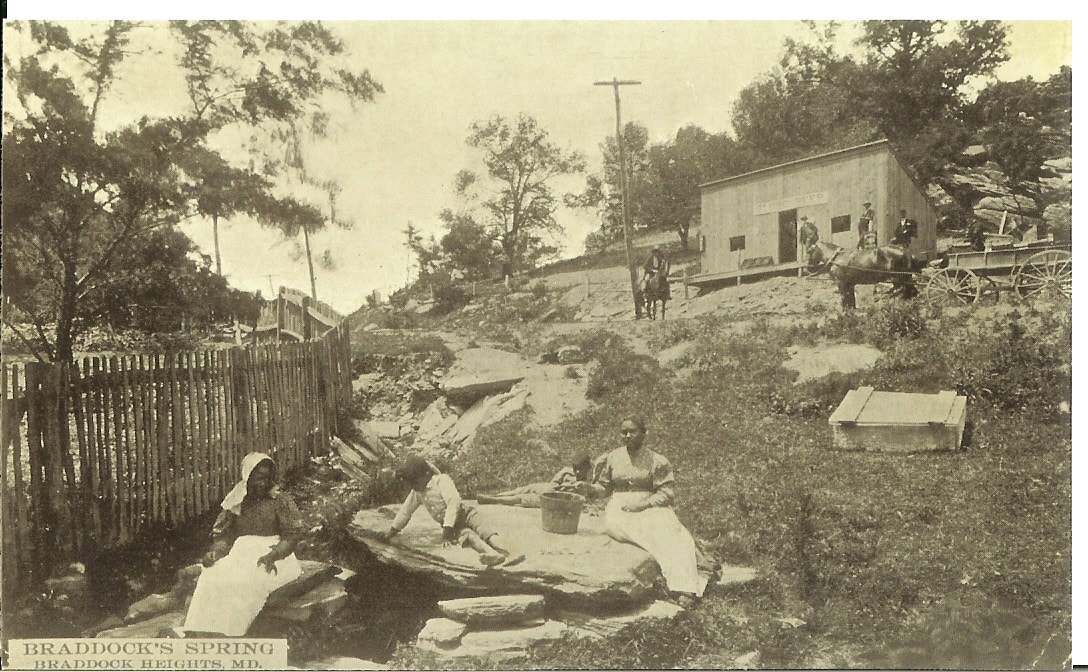

This past weekend was dedicated to US Presidents, past and present. The annual POTUS lovefest is sandwiched between the birthdays of two of the greatest of the profession—Abraham Lincoln on February 12th and George Washington on February 22nd. It’s not only the perfect time to buy a new mattress, but more so, to reflect upon these unique individuals and so many others who have held the position in the past. We have viable accounts of visits by both these legendary leaders to Frederick. Lincoln, who served from 1860-1865, came in early October 1862, weeks after the battles of Antietam and nearby South Mountain. He gave impromptu speeches at Court House Square and the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad station at the intersection of South Market and All Saints streets. George Washington made multiple trips through early Frederick Town, starting with a supposed meet-up with Gen. Edward Braddock of the British forces (during the French & Indian War) in April, 1755. On a later visit, while serving in the role as our very first United States president from 1789-1797, Washington would receive a special address upon his arrival at Frederick on June 30th, 1791. “At the request and in behalf of the inhabitants of Frederick” signed by George Murdock, William M. Beall, Richard Potts, Dr. Philip Thomas, and John McPherson, and reads: “The inhabitants of Frederick take the liberty to congratulate you upon your safe Arrival at this place. And to Assure you that it gives them sincere pleasure to have this opportunity of expressing that veneration and attachment which they have always felt and still feel for your person & character, As A Patriot, a soldier, A Statesman And a fellow citizen. They have Sir a lively sense of gratitude for that long Series of Services which you have so ably exhibited on the public Stage on behalf of your Country, and from which they, in common with the rest of their fellow citizens, have experienced Such Solid Advantages. They consider you, under heaven, as the chief Author of their political Salvation; And At the time that they profess their firm attachment to your person as their chief Magistrate, And to that excellent Constitution over which you preside, they are happy in the blessings derived from your Administration; And as republicans have a pride in Admiring that equality that hath been established, and which they hope will ever prevail throughout United America. They gratefully Acknowledge the blessings of Providence conferred by your safe return in good health from your long Southern tour at an unhealthy season of the Year, and pray heaven that it may very long be preserved here, & that you may be finally happy hereafter.” The following day, President Washington would write the following letter of thanks to residents who had just hosted him here: “Gentlemen, I express with great pleasure my obligations to your goodness, and my gratitude for the respectful and affectionate regard which you are pleased to manifest towards me. Your description of my public services over-rates their value, and it is justice to my fellow-citizens that I should assign the eminent advantages of our political condition to another cause—their valor, wisdom, and virtue—from the first they derive their freedom, the second has improved their independence into national prosperity, and the last, I trust, will long protect their social rights, and ensure their individual happiness. That your participation of these advantages may realise your best wishes is my sincere prayer. G. Washington” Upon the deaths of both men, Frederick would host special events including a luminary procession through the streets following Lincoln’s assassination in April, 1862, and a memorial funeral service for Washington in February of 1800. Our town, and county of the same name, has many connections to individuals who held the special title and position of President of the United States. In earlier days, Frederick was simply a town located on the crossroads of major transportation routes. Our history books claim that Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson traveled through town by stage and visited the Old Tavern that once stood at the intersection of West Patrick and Jefferson streets. Many other early presidents and important statesmen would do the same. It also doesn’t hurt having the presidential retreat on Catoctin Mountain up near Thurmont. This location, built in 1942, has hosted presidents starting with Franklin D. Roosevelt, our 32nd president, up through memorable visitors such as Lyndon Johnson, Jimmy Carter, and Ronald Reagan. Most recently, Joe Biden spent Christmas 2023 at the mountain getaway. As many know, I’m the historian and preservation manager for Frederick’s historic Mount Olivet Cemetery. I often get the chance to make both Frederick and Mount Olivet connections to former U.S. presidents through my weekly “Stories in Stone” blog, which can be found on MountOlivetHistory.com and Mount Olivet’s FaceBook page. We have decedents here that personally interacted with the presidential greats including the fore-mentioned George Washington and Abraham Lincoln. In addition, Mount Olivet may be the final resting place of the mysterious mixed-race daughter of Thomas Jefferson named Harriet Heckman. Its definitely known that we have a confidante of President Andrew Jackson in Francis Scott Key. Maryland’s only “Roughrider,” Jesse C. Claggett, charged San Juan Hill under future president Teddy Roosevelt, while John Groff served as a White House security guard under President Warren G. Harding. Sadly, Groff would die on the job in 1921. Dr. Basil Norris, the personal presidential physician to presidents Andrew Johnson and Ulysses S. Grant, owned cemetery plots here, but would be buried in San Francisco instead. Surprisingly, James Monroe’s grandson, Samuel L. Gouverneur, is buried a short distance away, also in Mount Olivet’s Area G. I thought we may have Carroll Harrison Kehne (1910-1994) buried in Mount Olivet, the man who served a Coke to President Harry Truman in 1953, but he is buried in my old stomping grounds of Yellow Springs/Indian Springs at Pleasant Hill Cemetery, near the new development of Kellerton. As far as presidents on the grounds, we have had only one that I know of, but should have had two. President William McKinley was invited to attend the unveiling of the Francis Scott Key Monument in August of 1898, but had to respectfully decline because he was in the middle of the Spanish –American War. Our largest president, William Taft would make it to the Key Monument in order to lay a wreath in November, 1911. Speaking of Key, President George H. W. Bush landed within yards of the cemetery back in 1991 aboard Marine One in order to attend a Frederick Keys baseball game. I was at that game operating the centerfield camera with a secret service agent right beside me. In addition to his grandson, the president’s central companion that night was M. J. Grove, son of the stadium’s namesake James Henry "Harry" Grove. Both Groves are buried in Mount Olivet as well.  In recent memory, locals can remember visits to town by President Dwight Eisenhower, whose wife (Mamie) loved to shop here. Ike's successor, John F. Kennedy, had a campaign stop in downtown Frederick in 1960, and later skied at Braddock Heights with his family. Kennedy’s presidential opponent, and a later U. S. president himself, Richard F. Nixon, “partied” at Braddock Heights as a senator when the mountain retreat was still in its heyday. He also visited Fort Detrick in October, 1971 to announce a new mission of researching cancer before signing the National Cancer Act. I also know that the Clintons stopped in the old Frederick Visitor Center on East Church Street and shopped at our antique stores including Great Stuff By Paul on Chapel Alley. Back in February of 2018, I wrote a “Story in Stone” on a past clerk of our Frederick County Court named Eli G. Haugh. Mr. Haugh, of no relation to me, had issued a fishing license to our 31st president, Herbert Hoover. Hoover enjoyed recreating in the Thurmont vicinity at Little Hunting Creek, near the old Catoctin Furnace below Thurmont, before President Roosevelt put his plan for Shangri-La (later to be named Camp David by President Eisenhower). As a matter of fact, Hoover’s personal secretary, Lawrence Richey, went as far as purchasing two properties for his boss’ recreational use. These included the old Furnace master’s home at Catoctin Furnace, and later Trout Run further south. Catoctin Furnace was built by Governor Thomas Johnson and brother James Johnson, the original furnace-master who lived in this home before building Springfield Manor down the road. Seven years back, I wrote about a brother of this tandem named Joshua Johnson (1742-1802), as he is buried with these siblings in a family plot in Mount Olivet's Area MM. Joshua was father-in-law to John Quincy Adams, son of our second president, John Adams, whom Governor Thomas Johnson served with on the Continental Congress. Joshua’s daughter, Louisa Catherine Johnson, would marry John Quincy Adams (1767-1848) in 1797.  President John Adams (1735-1926) President John Adams (1735-1926) Quincy would fulfill duties as the first US minister to Russia, followed by an appointment as envoy to Great Britain where he met Louisa. The couple came back to the United States after Quincy was appointed to the position of Secretary of State in 1817 under President James Monroe. He held this position until 1825, when he was elected as the 6th President of the United States. In doing so, Joshua Johnson’s daughter became the first-lady of the nation. Let’s jump back to our second president, John Adams, who made a brief visit, himself, to Frederick in late May, 1800. He was traveling from Philadelphia by carriage to the newly constructed executive mansion (White House) in the new capital of Washington, DC. The website “ghostsofdc.org” recounts the visit as follows: “The traveling party reached the town of Frederick, Maryland in the evening of Saturday, May 31st. He was greeted near the Monocacy River, about three miles outside of the town by Doctor Tyler, ironically a Presidential elector who supported Jefferson and not Adams. The following day, being a Sunday, saw the President and (nephew and personal secretary William) Shaw attend religious services at the Lutheran Church, conducted by Rev. Samuel Knox. The sermon focused on text from the book of Matthew: “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called the children of God.” They set out from Frederick with the destination of Georgetown, their first stop across the District line. Both Dr. William B. Tyler (1784-1872) and Rev. Knox (1756-1832) are residents of Mount Olivet, and the route used by John Adams (South Market Street turning into the Old Georgetown Pike) would have taken him directly past what would be our cemetery’s front gate 54 years later. Two years back, I wrote a story about people buried in Mount Olivet who are named after presidents. Trust me, there are many “George Washingtons” here, but you will also find the likes of Franklin Pierce Benner, Millard Fillmore Lease and Woodrow Wilson Miller One such person in Area C/Lot 62 was named for a president who has an extra special spot in Frederick’s history. Or should I say, we have a distinct spot in this gentleman’s personal and professional history. It’s not definitive, but it’s an interesting story nonetheless. Our cemetery resident is named for another president with a February birthday—William Henry Harrison. Our Mount Olivet “Tippecanoe” was born November 13th, 1848. He was the son of Josiah Harrison and wife Ann Rebecca Ludwig. He married twice and worked at the Birely Tannery for many years. The location of this operation was on the northside of Carroll Creek at a site across from the Delaplaine Arts Center. Mr. Harrison died on May 3rd, 1924. His obituary helps paint a better picture of this man. Nearly eight years before our Mr. Harrison’s birth, Frederick played host to the 9th US President of the same name. He would be here for roughly 18 hours, but they could have been hours that definitely changed his life. On February 5th, 1841, the President-elect (William Henry Harrison) arrived in Frederick. Nicknamed “Old Tippecanoe,” Harrison was on his way to office in Washington, from his native Indiana, after soundly defeating the incumbent candidate President Martin Van Buren. Before I get to the scant details of his visit, I want to share some background on a very complex man in the history of our country who is known better for his role as a soldier instead of politician. Here is some of the narrative found on his Wikipedia site: William Henry Harrison was an American military officer and politician who served as the ninth president of the United States. Harrison died just 31 days after his inauguration as president in 1841, making his presidency the shortest in U.S. history. He was also the first U.S. president to die in office, causing a brief constitutional crisis since presidential succession was not then fully defined in the United States Constitution. Harrison was the last president born as a British subject in the Thirteen Colonies and was the paternal grandfather of Benjamin Harrison, the 23rd president of the United States. Harrison was born into the Harrison family of Virginia at their homestead, Berkeley Plantation. He was a son of Benjamin Harrison V, a Founding Father of the United States. During his early military career, Harrison participated in the 1794 Battle of Fallen Timbers, an American military victory that ended the Northwest Indian War. Later, he led a military force against Tecumseh's confederacy at the Battle of Tippecanoe in 1811, where he earned the nickname "Old Tippecanoe.” He was promoted to major general in the Army during the War of 1812, and led American infantry and cavalry to victory at the Battle of the Thames in Upper Canada. Harrison's political career began in 1798, with an appointment as secretary of the Northwest Territory. In 1799, he was elected as the territory's non-voting delegate in the United States House of Representatives. He became governor of the newly established Indiana Territory in 1801 and negotiated multiple treaties with American Indian tribes, with the nation acquiring millions of acres. After the War of 1812, he moved to Ohio where, in 1816, he was elected to represent the state's 1st district in the House of Representatives. In 1824, he was elected to the United States Senate, though his Senate term was cut short by his appointment as Minister Plenipotentiary to Gran Colombia in 1828. Harrison returned to private life in North Bend, Ohio, until he was nominated as one of several Whig Party nominees for president in the 1836 United States presidential election; he was defeated by Democratic vice president Martin Van Buren. Four years later, the party nominated him again, with John Tyler as his running mate, under the campaign slogan "Tippecanoe and Tyler Too.” Harrison defeated Van Buren in the 1840 presidential election. The president-elect was 68, and certainly not in perfect health. His trip to Frederick was a long one during which he traveled in boat, stagecoach and steam cars. At every town, village and crossroads along the National Pike, residents gathered to greet him. Harrison had come to Frederick directly from Hagerstown via the National Road, which is represented by today’s US 40A. He had come through Boonsboro and traveled eastward over South Mountain to Middletown. From here, Harrison’s entourage scaled Braddock Heights and Catoctin Mountain and traversed the Golden Mile long before it was, well, “Golden.” Frederick diarist Jacob Engelbrecht wrote of the momentous occasion in his legendary diary: “General William Henry Harrison, President-elect of the United States, arrived in this town this evening about half past six o’clock. He stopped at Dorsey’s City Hotel.” Friday, February 5, 1841 Other accounts have said that by the time Harrison arrived in Frederick, he was very tired. He supposedly mustered enough strength to attend a Frederick reception at the City Hotel on West Patrick Street, located where the old Francis Scott Key Hotel is today near the corner of Court Street. This, of course, was the former Talbott’s Tavern, purchased by Baltimore business entrepreneur Daniel Dorsey in 1838. After improving the hotel, which had hosted the Marquis de Lafayette less than 20 years earlier, Col. Dorsey (1811-1885) ran the operation for six years before going back to Baltimore and taking over a popular hotel called the Exchange. He would manage hotels in New York and eventually the renown Barnum's City Hotel in Baltimore as he had married into the family. Col. Dorsey is buried in Baltimore's Greenmount Cemetery. Let’s get back to William Henry Harrison. After supper, the president-elect is said to have addressed the citizens outside in the cold rain. An exhausted Harrison thanked the people of Frederick for their hospitality and expressed his appreciation to the people of Maryland for their votes in the election. Having spent the night at this location in Mr. Dorsey's City Hotel, Gen. Harrison again met with the Frederick faithful. This eventually won over some of his opponents as Engelbrecht made a second notation in his journal: “This morning at 9 o’clock General Harrison addressed the people on a rostrum before the City Hotel (being first welcomed to our city by L. P. W. Balch, Esquire). The whole pavement and street was crowded. He departs in the cars at 10 1/4 for Baltimore. Saturday, February 6, 1841 I became intrigued with the name of the master of ceremonies, one L. P. W. Balch. I soon learned that the L. P. W. stood for Lewis Penn Witherspoon Balch. Mr. Balch was a leading lawyer in town and resident of Court House Square at the time of Harrison's visit in 1841. L. P. W. Balch was born December 31st, 1787 in Leetown, Jefferson County, Virginia (now West Virginia). His father, Rev. Stephen Bloomer Balch was a noted clergyman who helped establish Frederick's Presbyterian Church. Here is a little blurb on that gentleman. In 1840, L. P. W. Balch worked as a lawyer and can be found living in Court House Square with Frederick heavy-hitters including Dr. William Tyler, Richard Marshall, Nicholas Potts, and Fairfax Schley. His name can be found in early newspapers advertising his services and acting as trustee in real estate and other property sales and auctions. Balch's wife Elizabeth Willis Wever (1790-1874), was the sister of Caspar Willis Wever (1786-1861), an engineer builder involved in the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, and the creator of Weverton, Washington County, Maryland, an early industrial village that failed. Balch would leave Frederick to take over his family estate in Jefferson County, Virginia (later West Virginia). Before his death, he would serve as Judge of the Jefferson County Circuit Court. Engelbrecht’s reference above to Harrison departing in“the cars,” meant the rail cars and railroad. The Baltimore & Ohio was still relatively new, having first connected Frederick to Baltimore a decade earlier in 1831. The freight depot was on Carroll Street and the old passenger station, which still stands, was located on the southeast corner of S. Market Street at the intersection with East All Saints Street. (A later incarnation of the station is today the home of Frederick’s Community Action Agency at 100 S. Market). Harrison was escorted to the depot and took a train to Baltimore where he would next enjoy hospitality at Barnum’s City Hotel said to have been "one of the finest hotels in the mid-Atlantic.” Harrison reached Washington from Baltimore, but would never make it back to Frederick, among many other places. Three weeks later, he would be inaugurated on March 4th. “When Harrison came to Washington, he wanted to show that he was still the steadfast hero of Tippecanoe and that he was a better educated and more thoughtful man than the backwoods caricature portrayed in the campaign. He took the oath of office on Thursday, March 4, 1841, a cold and wet day. He braved the chilly weather and chose not to wear an overcoat or a hat, rode on horseback to the grand ceremony, and then delivered the longest inaugural address in American history at 8,445 words. It took him nearly two hours to read, although his friend and fellow Whig Daniel Webster had edited it for length. Harrison’s inaugural address was a detailed statement of the Whig agenda, a repudiation of the policies of his predecessors Andrew Jackson and Martin Van Buren. It was also the first and only formal articulation of his approach to the presidency. Likely reminiscent of his speech in Frederick in early February, Harrison’s address began with his sincere regard for the trust placed in him: “However strong may be my present purpose to realize the expectations of a magnanimous and confiding people, I too well understand the dangerous temptations to which I shall be exposed from the magnitude of the power which it has been the pleasure of the people to commit to my hands not to place my chief confidence upon the aid of that Almighty Power which has hitherto protected me and enabled me to bring to favorable issues other important but still greatly inferior trusts heretofore confided to me by my country.” President William Henry Harrison promised to re-establish the Bank of the United States and extend its capacity for credit by issuing paper currency in Henry Clay's American system. He intended to rely on the judgment of Congress in legislative matters, using his veto power only if an act were unconstitutional, and to reverse Jackson's spoils system of executive patronage. He promised to use patronage to create a qualified staff, not to enhance his own standing in government, and under no circumstance would he run for a second term. He condemned the financial excesses of the prior administration and pledged not to interfere with congressional financial policy. All in all, Harrison committed to a weak presidency, deferring to "the First Branch", the Congress, in keeping with Whig principles. He addressed the nation's already hotly debated issue of slavery. As a slaveholder himself, he agreed with the right of states to control the matter: “The lines, too, separating powers to be exercised by the citizens of one state from those of another seem to be so distinctly drawn as to leave no room for misunderstanding…The attempt of those of one state to control the domestic institutions of another can only result in feelings of distrust and jealousy, the certain harbingers of disunion, violence, and civil war, and the ultimate destruction of our free institutions.” This was very telling of the future as we would have states rebelling and dropping from the Union with the American Civil War twenty years later as Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated for his first time as president. Following his speech, William Henry Harrison rode through the streets in the inaugural parade. He would stand in a three-hour receiving line at the White House. He would wrap up what was likely the busiest and most stressful day of his life by attending three inaugural balls that evening, including one at Carusi's Saloon entitled the "Tippecanoe" ball with 1,000 guests who had paid $10 per person (equal to $325 these days). In the days following his March 4th (1841) inauguration, Harrison fell ill. This was just one month after his visit to Frederick. Some say that this sickness was the exacerbation of a cold caught while giving his speech in Frederick. Others say it was the result of the entire grueling journey from Tennessee. Yet others think it was a consequence of his conduct on Inauguration Day itself. More recent study has even said that it could have been enteric fever and have connections to Washington's questionable drinking water supply of the period. Harrison’s death continues to be speculated about. He would only serve 31 days, a period fraught with several stressful “job-related” situations and another rainstorm situation which caught him by surprise while on a morning walk on March 24th, 1841. The president became ill with cold-type symptoms and would be bed-bound with a “severe chill.” Within days, his doctor diagnosed him with pneumonia. In the early morning hours of April 4th, Harrison would die exactly one month after his inauguration, and 53 days after visiting Frederick. He was the first US president to die in office. Jacob Engelbrecht wrote on April 6th (1841) a brief passage of Harrison's death and instructions given to his successor, John Tyler, but nothing about the potential cold caught in Frederick: The last words uttered by General Harrison about 3 hours before his death in the presence of Doctor N. W. Worthington were, “Sir, I wish you to understand the true principals of the government. I wish them carried out. I ask nothing more.” General Harrison’s funeral will take place tomorrow at 12 o’clock AM. A 30-day period of mourning commenced and William Henry Harrison was buried in a family cemetery in North Bend, Ohio. I found it interesting that Jacob Engelbrecht would make the following entry in his diary nearly 33 years later on January 23rd, 1874 regarding presidents: I read this day in Gruber’s Almanack that we have had eighteen Presidents of the United States since we exist as a government viz. George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson, Martin Van Buren, William Henry Harrison, John Tyler, James K. Polk, Zachary Taylor, Millard Fillmore, Franklin Pierce, James Buchanon, Abrahan Lincoln , Andrew Johnson, Ulysses S. Grant. I was born during the Presidency of John Adams so that there were seventeen Presidents during my lifetime in these United States. I saw of these 17 the following, James Monroe, John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson, Martin Van Buren, William Henry Harrison, James Buchanon, Abraham Lincoln, Andrew Johnson, & Ulysses S. Grant. I reckon we’ll not see many more, past 76 years. Ironically, Jacob Engelbrecht died on President Washington’s birthday, February 22nd, 1878. He did vote in one more election, his 16th, and “his man won” in the form of Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio. Back in those days, the count actually took months to compile as Jacob journaled that he had voted on November 7th, 1876 and the final vote tally would not be made until March 2nd, 1877. With electoral votes, Mr. Hayes was victorious with 185 votes compared to his Democratic challenger Samuel J. Tilden who received 184.  Now, I’m not sure if Engelbrecht had an earlier opportunity to meet, or at least see, Rutherford B. Hayes when he was a Union commander during the Civil War. Lt. Col. Hayes came through Frederick in early September, 1862 and could have passed the diarist’s front door on West Patrick Street along Carroll Creek. This future president commanded the 23rd Ohio Regiment during the 1862 Antietam campaign and was severely wounded at Fox’s Gap during the September 14th Battle of South Mountain. He would recuperate for three weeks afterward at the home of local Middletown merchant Jacob Rudy. Just five months before his own death, Jacob Engelbrecht would make it “18 for 18” as he would see, and hear, President Hayes in person as an invited guest to the Great Frederick Fair. The diarist (and former Frederick mayor) estimated the crowd at 10 or 12,000—the largest ever to attend and on account of the President’s visit and address. The local Frederick newspaper would comment: ”Now he (the president) comes to see the triumph which agriculture has achieved under the broad banner of a united country.” President Hayes speech (October 11th, 1877): Ladies and fellow citizens, I thank you for the very cordial reception you have extended to me, and particularly I return my thanks to the people of Frederick city and county for their kindness in inviting me here. Of all the interests to be promoted by institutions like this the agricultural interests of the country are the most important. If the farmer is prosperous and the planter is prosperous, the country will surely be. Every interest finds an advantage in the promotion of agriculture, and if today we rejoice in reviving and returning prosperity to our nation it is because good crops and good prices make good times. We come, therefore to take part in this demonstration because it represents the agricultural interests of the country. Your county is well known throughout the Union. The skill and excellence of its cultivation are conceded, and in the locality from which I come we have the advantage of numbering amongst our citizens many who originally came from Frederick county. (applause) In Seneca and Sandusky counties, Ohio, there are many families who look back with pride to their early life in Maryland. They were familiar with this county in their boyhood, and in my acquaintance with them I do not feel a stranger to you. And their pride and boasting of their old home are great. The richest lands on the Sandusky are not, in their belief, as fertile as those of Maryland, and there are no fruit or crops like those of the county of Frederick, MD. And beside this I will remember the days I once spent here and the many kindnesses which I received, and on this account I feel at home amongst you. It’s so interesting to ponder the fact that these great individuals, the most powerful in American history, visited our fair town and county. Perhaps it was short and sweet, or somewhat insignificant in the grand scheme of events, but I think we will always see something romantic, magical and unique about past presidents being on our streets, sleeping in our buildings, shopping and dining in our stores and restaurants, and enjoying the tranquil atmosphere of Frederick and Frederick County, Maryland. Happy President’s Day, week and month! History Shark Productions Presents: Chris Haugh's "Frederick History 101" Are you interested in learning more about Frederick's incredible history?

Check out this author's latest online course offering: Chris Haugh's "Frederick History 101," with the next session scheduled as a 4-part/week course on Saturday mornings in March, 2024 (March 2, 9, 16, 23). These will take place from 9-11:30pm via the Zoom platform, all you need is a computer and you will be sent a link to view/hear the class. Cost is $79 (includes 4 classes). For more info and course registration, click the button below! (More sessions to come)

0 Comments

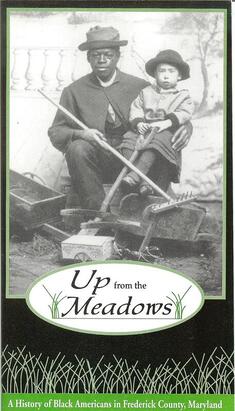

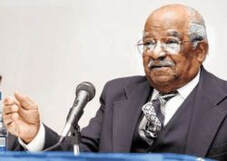

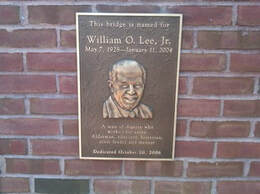

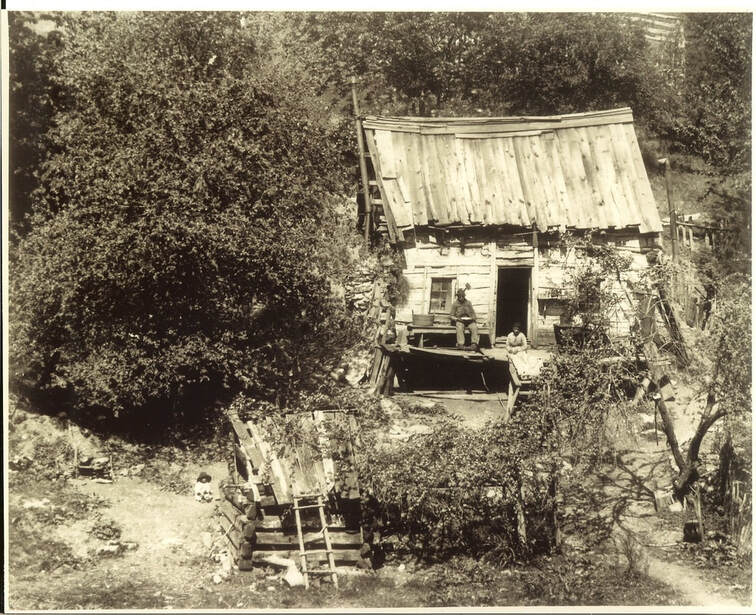

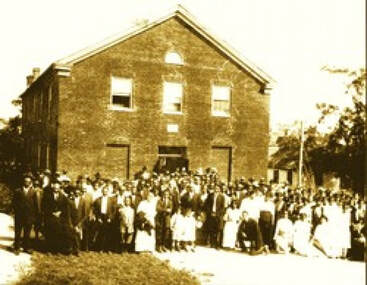

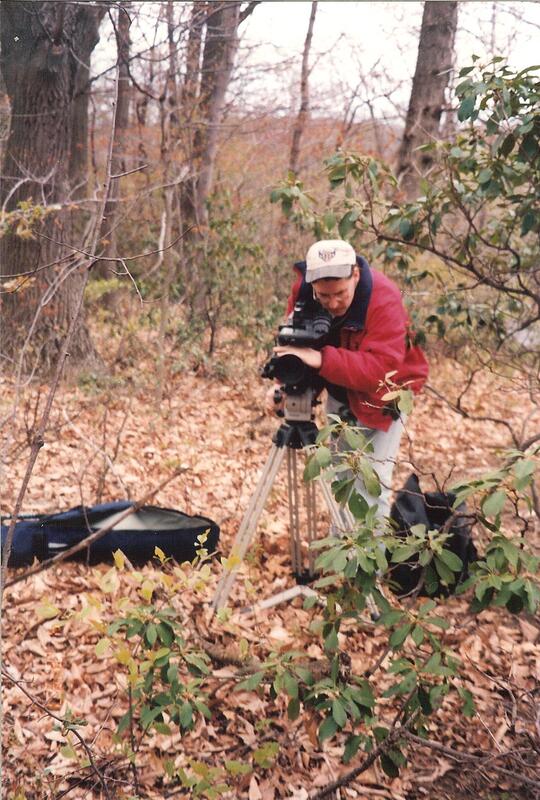

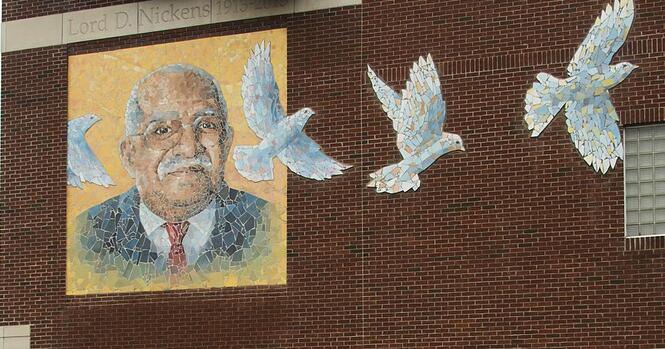

I am enjoying a period of great reminiscing of late. It was 30 years ago (February 1994) that I was inspired to produce a video-documentary project focusing on the Black history of Frederick County, Maryland. I wouldn't start production until two years later, and two years past that (March 1998), I surprisingly found myself on a stage in San Diego, California accepting an award called the Beacon Award of Excellence, the highest honor for communications and public affairs in the Cable Television industry. It was quite a thrill, but more so, a humbling experience as this award belongs to my many "teachers" for this endeavor, along with a host of people I only knew as gravestones, sprinkled throughout the county —their spirits were certainly guiding me. The five-hour documentary was given the title Up From the Meadows, a play on the opening line from John Greenleaf Whittier’s famed poem about hometown Civil War heroine Barbara Fritchie. Throughout the production process, I was able to live in the moment, as I knew that creating this long-form television program would not only educate and humble me (a white male born at the tail-end the Civil Rights Movement period) but would certainly shape my thinking about past events, places and persons. I went into the project with the basic Black history knowledge I had carried since my childhood and early school days. There were the obvious stories of Martin Luther King, Rosa Parks, George Washington Carver and Jackie Robinson. I also could make connections to my home state through legendary native Marylanders: Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, Benjamin Banneker and Thurgood Marshall. When I was 10 years old, my parents encouraged me to watch the “Roots” television miniseries, which premiered in 1977. Like countless other Americans, black or white, I became inspired toward a lifetime search to know my own ancestors. However, the greater takeaway was getting my first glimpse of a dramatization of the African slave trade and the institution from Colonial America up through the American Civil War, and continued prejudice and segregation that would permeate society in the century to follow. It made quite an impression. From time to time, I thought about delving into a Black history of Frederick, and was inadvertently pushed over the threshold by the late Dr. Len Latkovski (1943-2015), beloved former professor of history and political science for Hood College. I had utilized Len as an on-screen commentator for an earlier Frederick City history documentary entitled Frederick Town which I began producing in 1993. The seasoned professor, originally from Latvia, amazed me with population statistics and anecdotes relating to Frederick County’s slave and free black populations. He also encouraged me to look at slavery through the lens of different religions and their views on slavery (particularly Catholicism, Methodism and the Society of Friends). Len made me realize that Frederick County’s past made for a unique case study of the African-American experience. Where else could you find such a great number of free and enslaved black people living in the same environs—a place bordered by the Mason-Dixon Line to our north, and the Potomac and Virginia, capital of the Confederacy to our south? And all this set in motion and dictated by the original white European cultural-settlement patterns of Frederick County. I would zero in on this “border county within a border state” notion as a central tenet for my proposed “Black history” documentary. My experiences with Up From the Meadows have been readily coming to mind over the past few month. I’ve been preparing lectures and readying materials for an upcoming, multi-week class on the subject that I am slated to teach (in March and April) under my History Shark Productions moniker. Students will view portions of the documentary, interspersed with an illustrative PowerPoint presentation. I plan on explaining the production process, and discussing pertinent points of subject matter. Simply put, the four-part course will be “chock-full” of historic events, places and people from Frederick County’s past that once hovered “below the proverbial radar.” And for a story this rich and important, I can’t say I will be teaching alone. I will have a host of on-screen instructors helping me out, just as they did back in March 1997 with the program’s premiere on local cable television.  Dr. Blanche Bourne Tyree (1917-2019) Dr. Blanche Bourne Tyree (1917-2019) One of these “teachers” was Blanche Bourne Tyree, who holds the distinction of being the first woman from Frederick County to have earned a medical degree. She had a successful career as a pediatrician and a public health administrator for over 40 years. In retirement, she built an impressive resume of civic involvement, including a three-year stint as co-host of Young at Heart: Frederick County Seniors Magazine, a program I proudly oversaw as executive producer while at GS Communications' Cable 10. Medicine would certainly define Blanche Bourne Tyree’s immediate family’s life. Her father was a man named Dr. Ulysses Grant Bourne, Frederick’s first Black physician. Dr. U.G. Bourne hailed from Calvert County, and came to segregated Frederick in 1903, after completing his education in North Carolina at Leonard Medical College. Despite being allowed to practice at Frederick Memorial Hospital, Dr. Bourne went on to open a 15-bed hospital for Blacks on West All Saints Street in 1919. This would be the first county hospital to accept patients of color. Dr. Bourne was a magnificent civic leader as well, whose many accomplishments include the founding the Maryland Negro Medical Society and co-founding Frederick’s NAACP chapter. His name now adorns the Frederick County Government building formerly known as the Montevue Assisted Living Facility (located on Montevue Lane). His other two children experienced success in the healthcare field as well. Dr. Ulysses Grant Bourne Jr. became the first Black doctor to have privileges at Frederick Memorial Hospital, while daughter Gladys (Bourne) Thornton became a nurse. As snow and freezing rain fell outside, I fondly recall visiting Blanche at a local nursing home back in February, 2016. The 98 year-old had been plagued by recent setbacks which precipitated this stay away from her Crestwood Village home. I thought about how surreal things must have felt for a veteran physician and caretaker, now firmly in the role of patient. As I sat in awe of my beautiful friend, discussion on that morning included our past documentary and the day of our interview taping, one in which we were forced to “shoo” her late husband Chris (Tyree) out of the room we were using because he was interjecting too many comments from the “peanut gallery.”  Lord D. Nickens Lord D. Nickens We also recalled one of the true highlights of my professional career, something that began as a simple invitation Blanche had given me. This was in the early spring of 1998, and featured a road trip to find Blanche’s father’s original homestead and farm in lower Calvert County. I did the driving and along the way, we picked up Blanche’s cousin who would help guide us to the rural vicinity of Island Creek (near Broomes Island). This is where Blanche’s grandfather, Lewis Bourne, and wife Emily raised their ten children in a small rural Black settlement in the decades immediately following the Civil War. The old, family house had been boarded up for several years, slowly decaying into the surrounding landscape. I did, however, feel the importance of place here— having produced two generations of Bournes that would certainly shape Frederick into the great place we know today. With that 2016 visit, I again had the opportunity to thank Blanche for her assistance and friendship over the years, but especially with this project. She was my lone, surviving, on-camera commentator from the program which originally boasted 12 Frederick residents. It was moments such as the trip to Calvert County that helped give me a better understanding of Black history and legacy in Maryland, and of my home county in particular. As a white male, I will never be able to fully understand, but with this priceless tutelage, I was able to position myself as a conduit, relaying experiences from residents like Blanche who truly “lived” the documentary. Dr. U.G. Bourne was the father of one of my interview subjects, and mentor to another. Lord Dunmore Nickens (1913-2013) was truly influenced by Blanche’s dad, propelling him to take the lead in Civil Rights activism for the better part of his 99 years. Mr. Nickens taught me a great deal as well, and shared a myriad of personal experiences, “fighting the good fight,” on tape with me. He passed away more than a decade ago, but not before being honored with having a street in Frederick named after him. In 2014, a mosaic memorial mural depicting Mr. Nickens was unveiled on the side of a downtown building located at the corner of North Market and Lord Nickens streets.  Plaque honoring William O. Lee (1928-2004) adjacent Frederick's "Unity Bridge" in Carroll Creek Park Plaque honoring William O. Lee (1928-2004) adjacent Frederick's "Unity Bridge" in Carroll Creek Park Another Up From the Meadows alum was memorialized with a decorative suspension bridge crossing Carroll Creek. This waterway was once considered the dividing line between Frederick's white and black residents. William O. Lee (1929-2004) is best remembered as a longtime educator, municipal politician and community activist. This “gentle man” in the highest regard, can be credited as being among the first people to chronicle and promote Frederick City’s black heritage, highlighted by his childhood home of the All Saints neighborhood as the central hub for black life for well over a century. Mr. Lee walked me all over town, working hard to make sure I had a firm understanding of Frederick’s foremost endeavors in education, business, charity and social life in the segregated black community, and how barriers were finally chipped away in an effort to unite two Frederick’s into one—figuratively “bridging the town creek.”  Kathleen Snowden (1933-2008) Kathleen Snowden (1933-2008) What Bill Lee taught me about the city, Kathleen Snowden of New Market taught me on the county level. The self-proclaimed “outspoken” New Market resident shared her knowledge, based on years of intensive black history research. Ms. Snowden accompanied me as travel companion on several field trips. We searched for the remaining traces of former “Black sections” of leading towns (ie: Middletown, Brunswick, Libertytown) and explored “post-emancipation hamlets,” places like Sunnyside, Bartonsville, Della, Hope Hill and Coatesville. In addition, we experienced Black churches together, looked for old "colored" schoolhouses and walked countless Black burial grounds, seeing names in stone of former slaves and descendants of once-enslaved peoples, not to mention those of soldiers and prominent early free Blacks who lead their neighbors in the long fight towards equality.  Marie Erickson (1932-2011) Marie Erickson (1932-2011) Other teachers for me included 100 year-old Ardella Young of Pleasant View, Maude Morrison, Luther Holland, Arnold Delauter, Bessie Brown, Edith Jackson, Henry Brown and a lone, yet powerful white voice—Marie Anne Erickson. Marie taught me to embrace the fact that I was incapable of appreciating or fully understanding what my other subjects and the Black population (past or present) had experienced over their lifetimes. I was white, and male to boot, the long dominant power combination in our country since its inception. I had not experienced struggle of any kind, however I continue to feel no shame for events of the past, especially going back several generations. Marie Erickson was born and raised in Illinois, the daughter of Swedish immigrants who came to the US in 1923. She would pass in 2012, but not after four decades of assisting local Frederick Blacks in researching their roots, and gaining family connections. Marie was not only a friend to so many people of color, but became accepted as an “honorary” family member in many instances. All the while, she remained 100% genuine, not simply showboating for self-gain. Marie cared about equality and often looked for “teachable moments,” objects and opportunities in which to share illustrative “Black” stories and experiences with white and black readers alike. These appeared through her countless articles and letters to the editor in Frederick newspapers and magazines. A year after her death, Marie's daughter asked me to write the forward for a book to include many of her articles. This was published in late 2012 and is entitled, Frederick County Chronicles: The Crossroads of Maryland. As I said earlier, using Frederick County and its past for context, serves an amazing canvas to tell this story and introduce individuals such as William Ware, Elijah Lett, Professor James Neale, Decatur Dorsey, John W. Bruner and places like Oldfields, Centerville and Halltown. Current residents such as Joy Hall Onley and members of Frederick County's AARCH group (African American Resources Culture and History) continue their amazing work of "piecing together" and preserving this rich legacy. I might add that legendary resident, and founding AARCH member, Rose Chaney helped gather another group of amazing Black history storytellers for The Tale of the Lion, a documentary produced in 2018. Meanwhile, I’m happy to report that Black History Month will be extended through March and April this year for those individuals who take my upcoming “Up From the Meadows: the Class” course. While I market the fact that its my class, I think you can see that its only semantics. I will have plenty of help from former friends and mentors— true legends who helped research, preserve and make Frederick County's history, a mix of all colors when you really think of it. To learn more about the upcoming course (Tuesday evenings starting on March 12th-April 2nd), including registration instructions, click the button below:

|

AuthorChris Haugh Archives

February 2024

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed