HSP HISTORY Blog |

Interesting Frederick, Maryland tidbits and musings .

|

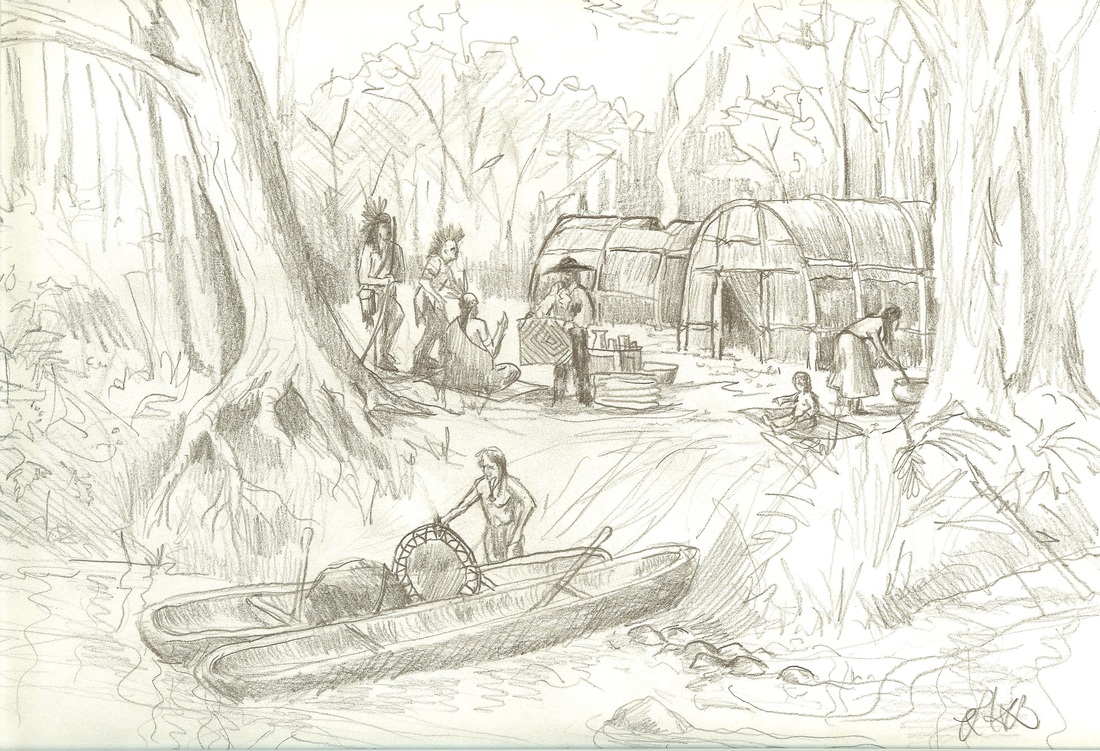

Quartzite Quartzite Well it sure sounds pretty ominous, but let me assure you that our monadnock is sweet and lovable—actually “sugary sweet,” at least in name. And we certainly aren’t talking about a creature like Sasquatch, Chupacabra or even the Snallygaster. What we have is a geologic phenomenon, and not one of biological creation. To start the conversation, I want to point out that we have rocks in our area that were formed in the early Paleozoic period of the Cambrian era. This was roughly 500 million years ago and the result is a rock called Weverton Quartzite. Quartzite was originally pure quartz sandstone before the conversion process of metamorphosis which consisted of heating and pressure related by techtonic compression. Put more simply, this is the compacted form of sand, perhaps coming from the shoreline of ancient beaches first turned into sandstone and later into quartzite. The mountains of Frederick County were formed at a time when most of our vicinity was underwater. The uplifting could have been caused by the collision of plates such as ours with Africa. Our mountains, when they were “brand, spanking new,” are said to have been as high as the Himalayas, and multiple times higher than younger chains such as the Rockies. Our ancient Catoctin Mountain (and South Mountain) wore down over the next couple of million years thanks to erosive factors.  "Sunset Sugarloaf Mountain, Dickerson, MD" by artist Mimi Betz "Sunset Sugarloaf Mountain, Dickerson, MD" by artist Mimi Betz The most unique of our vicinity’s landforms, the picturesque Sugarloaf Mountain, is really not a mountain in the general sense. Rather it is better known as a monadnock. And what’s a monadnock you ask? A monadnock is a unique geologic creation of a landform resembling a mountain that remains after erosion of surrounding land, but not uplifting of the earth’s crust. These are isolated mountains in a general sense. Created the same time as the Blue Ridge mountains, geologists conclude that Sugarloaf Mountain represents the original elevation of the area around it, and took approximately 14 million years to form. This can be blamed in part on the quartzite cap at the summit which as highly resistant to erosional factors as opposed to the surrounding underlying limestone of Carrollton Manor. Just imagine the analogy of holding an umbrella over yourself during a downpour of rain. Everything around you gets soaked, but not you.  It is thought that the early French-Canadian fur traders named the mountain at the turn of the 17th century. The landform resembled the way blocks of sugar, in conical form, were being sold in Europe and also packed for sea voyage. They consisted of the top representing the clumped sugar peeking out from a green or brown paper wrapper. Two of our area’s first European explorers were Franz Ludwig Michel and Baron Christoph Von Graffenried. Both were from Switzerland and had the opportunity to climb the monadnock in the first decade of the 1700’s. In his diary, Graffenried claims that the traders call the mountain “pain du sucre.” He likely learned this from his guide up the mountain, a reknown French Canadian fur trader named Martin Chartier. Chartier was married to a Shawnee woman, had a large contingent of Shawnee followers and operated a trading post at the mouth of the Monocacy around 1712-13. Just for trivial effect, I will share that one of the most famous monadnocks in America is Pilot Mountain, located in Surrey County, North Carolina. It is located near Mt. Airy, the real hometown of television legend Andy Griffith. Now for the Andy Griffith television show of the 1960’S, Sherriff Andy Taylor lived in Mayberry (a play on Mt. Airy). The neighboring town (on the show) was Mount Pilot, which takes its inspiration from Pilot Mountain. And as far as Sugarloaf mountains, we are not alone. They exist in several states: Michigan, Maine, Massachusetts and New York, along with other countries—Ireland, Australia, Canada and Japan. However, the most famous Sugarloaf Mountain of them all is located in Rio de Janiero (Brazil).

2 Comments

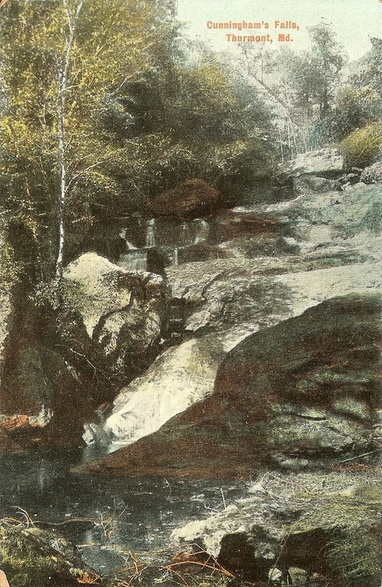

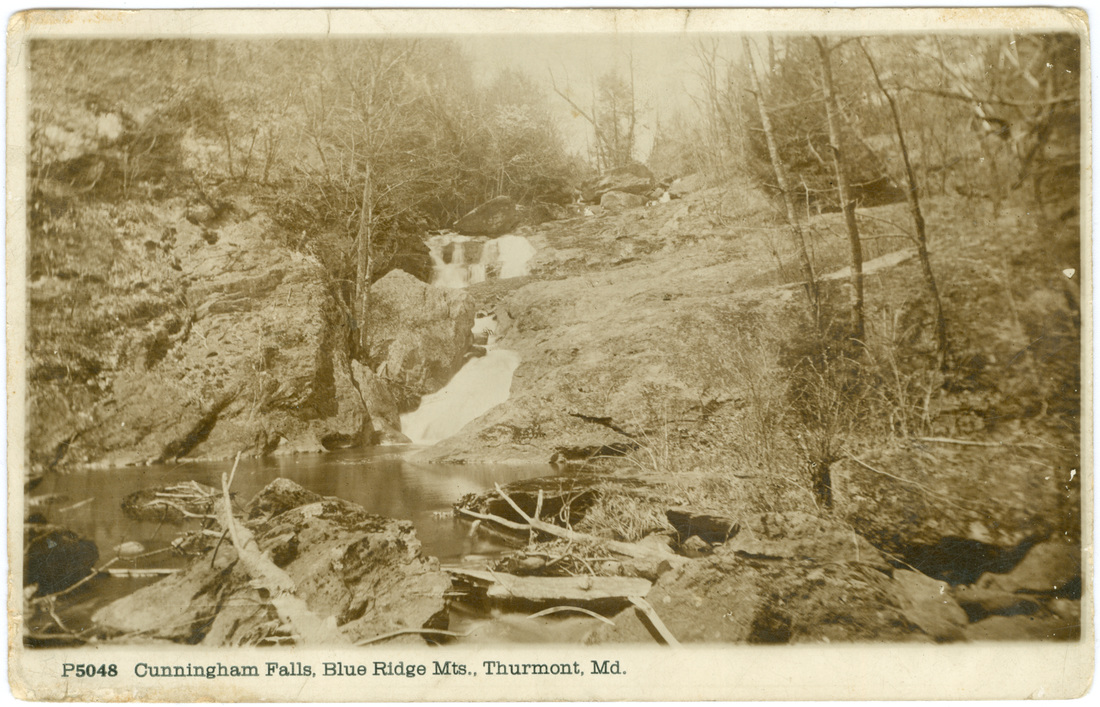

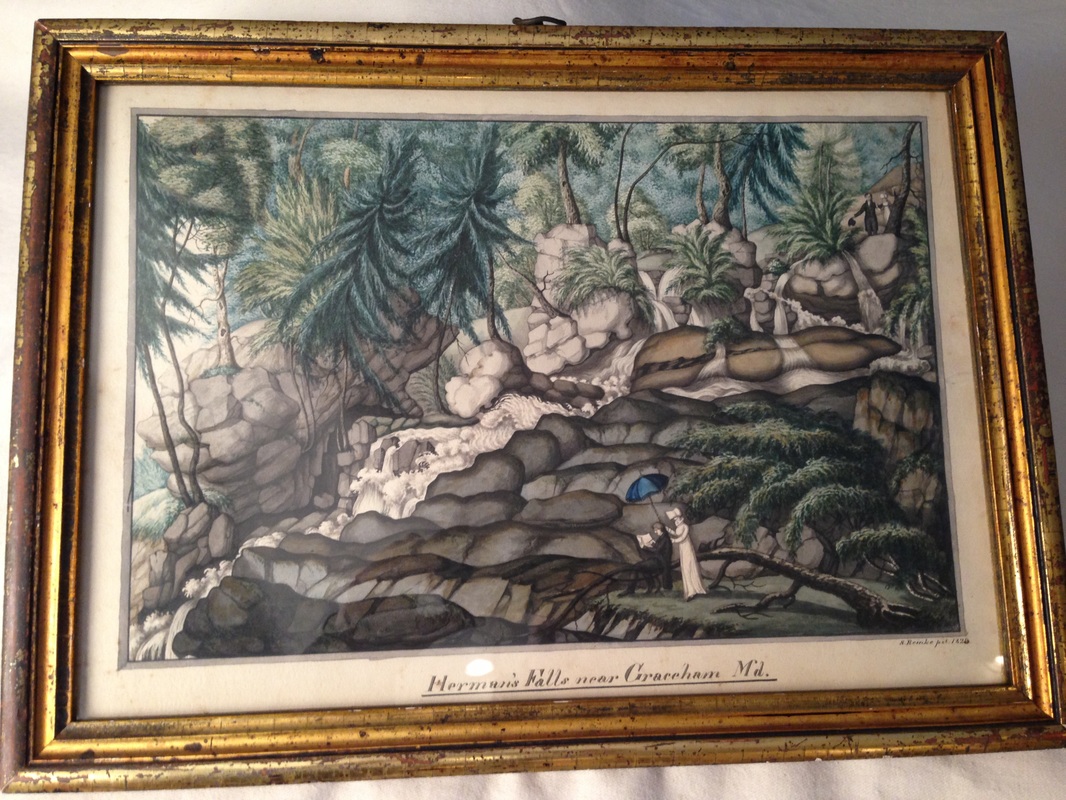

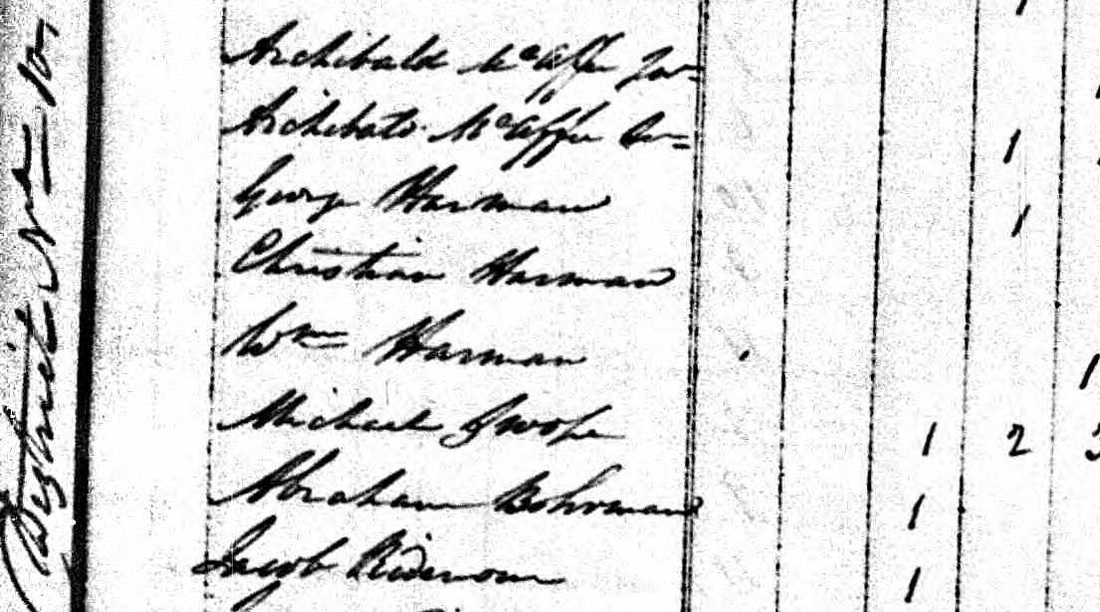

This past Saturday, my youngest sons and I made a pilgrimage to Cunningham Falls State Park for the annual Maple Syrup Demonstration. This was the 46th edition of the popular event which is held in, and around, the Houck Lake Area of the park. For my youngest son Eddie and I, it’s been an annual rite of Spring as this was our 9th consecutive visit (he’s been going since age 1). In recent years, we have had the opportunity to share this tradition with my stepsons (Eddie’s stepbrothers). One of which, Vinnie made the sojourn this year.  The magic of pancakes with plenty of maple syrup! The magic of pancakes with plenty of maple syrup! The “Maple Syrup” event is always a great Frederick County experience, and you never know what the March weather will hold be it lamb, lion or something in between. An ode to maple syrup in a great natural, park setting seems to attract plenty of folks each year (and from out of the Frederick area as well): south central Pennsylvania, the panhandle of West Virginia, Washington, Carroll and Montgomery counties (Maryland), DC and Northern Virginia. How can things be bad when you can start off your visit with a pancake breakfast—a perfect sampling experience for Maryland-made maple syrup. That’s right Vermont….so back off! The festival occurs over two weekends in mid -March and features “maple syrup boiling” demonstrations and family entertainment and crafts. For us, and many others, the trip is always capped with a short hike up to the namesake Cunningham Falls. To both young and old, this is quite an accomplishment, especially in respect to counteracting the effects that pancakes and syrup have on the human body.  The famed Cunningham Falls has intrigued me more and more each year, and not for the geologic reasons you would think. Cunningham Falls is not your typical waterfall like the legendary Niagara, Great Falls down the Potomac towards DC or Muddy Creek Falls out in Garrett County. Instead, ours is a cascading waterfall, and not just any cascading waterfall—it’s the largest cascade in the state. The other day, we walked to “the Falls” amidst a light snow—pretty amazing, since my boys had baseball practice just a few days prior with the temperature hovering in the 70’s. We had our customary picture taken for archival and “FaceBook” purposes. As we started making our way back off the boardwalk observation area, I heard another Dad proudly telling his family about the origin of the the Falls and its mysterious name. He said: “This used to be called McAfee Falls after the original owners of the land. Then the government took it away from them, and renamed it “Cunningham Falls.”  Hunting Creek Gap (aka Harman's Gap) Hunting Creek Gap (aka Harman's Gap) I just smiled walked by, not particularly in the mood to share a history lecture with this gentleman as he surely deserved a bit more of “rest of the story.” I had stumbled over a bit more, but not all, of the Cunningham Falls “name game” a few years back when I was researching and compiling a documentary on nearby Thurmont, entitled “Almost Blue Mountain City.” The story actually goes back to colonial times and the first Europeans in the area. Now thousands of years of native habitation likely included several other monikers for this geologic water form that we will never un-earth. In the mid 1700’s, German settlers were winding their way down into the Maryland colony from Pennsylvania via the aptly named German Monocacy Road. Some stayed and settled here, while others continued in a southwesterly fashion, heading into the Shenandoah Valley heading south. The romantic story of the immediate area says that the Weller family camped at Cold Spring because of a sick child. The child died, but the family decided to stay, making them the first European settlers of the area in 1751. Again, I’d like to insert the word “story” here because it is not the definitive way things happened, but that’s a blog for another day.  What is certain is that the “Great Road” west of (what would one day become) Thurmont crossed over, and through, Catoctin Mountain. Today this is Maryland route 77, also known as Foxville Road. Amidst the beautiful scenic views of trees, streams, rocks and “the cascading falls,” the sometimes treacherous and “zig-zagging” road is much improved compared to its rustic beginnings. All this is relative because this road, at the time, certainly made Colonial era travel possible over the large landform of Catoctin Mountain. Travelers, pioneers, businessmen and farmers used this transportation route regularly, and at least one person used it “religiously.” This was Graceham Moravian Church minister Samuel Reinke (1791-1875).  Grave of Rev. Samuel Reinke (1791-1875) in Moravian Cemetery, Bethlehem, PA. Grave of Rev. Samuel Reinke (1791-1875) in Moravian Cemetery, Bethlehem, PA. Reverend (and later Bishop) Reinke served the Graceham congregation from 1827-1835. During this time, the cascading waterform was the key “tourism highlight of the area.” It certainly was not called Cunningham Falls back then, rather it was known as Hermann’s (or Herman’s Falls) by the late 1700’s and early 1800’s. We know this based on a watercolor Reinke painted, dated 1828. Like me, Rev. Reinke likely brought his own young sons here to the falls as well. Ironically, his oldest was named Edwin just like mine, but I’m guessing the nickname “Eddie” wasn’t in vogue back then. Instead of a Vinnie, he had other sons named Amadeus and Clement. All three offspring would follow in their father’s life work as ministers, with Rev. Amadeus A. Reinke serving at Graceham’s faith leader from 1849-1854. The Hermann Family (anglicized to Harman) originally settled in the area in the 1770’s and owned the cascading waterfall depicted by Reinke in a watercolor painted in 1822. Original settler Marcus Hermann, Jr. was a descendant of Augustine Hermann, an early Maryland mapmaker and owner of Bohemia Manor in Cecil County. Marcus Hermann had purchased land from Leonard Moser, a 30-acre tract of property called “Nolin” or “Knoll-in” Mountain. Sometimes this has been referred to as Noland’s Mountain as well. Regardless, the Hermanns would also own the “Cold Spring” property to the east, and this gave birth to the origin of the name “Harman’s Gap.” Marcus’ children would eventually intermarry into the McAfee family by the late 1800’s and the falls would become known more commonly by another name, McAfee Falls. However, the McAfee family is said to have called the cascade ”Hunting Creek Falls.” The federal government in the 1930’s laid claim to much of the mountain land including that of the McAfees. After years of making charcoal (to fuel nearby iron furnaces), mountain farming, and harvesting of trees for timber, land was purchased by the federal government to be transformed into a productive recreation area, aimed at bringing land back to its original condition while providing meaningful employment for people during the Great Depression. Beginning in 1935, the Catoctin Recreational Demonstration Area went under construction by both the Works Progress Administration and the Civilian Conservation Corps. The northern portion of the park was transferred to the National Park Service in 1936, and renamed and reorganized in 1954. The 5,000 acres south of MD77 were transferred to Maryland, becoming Cunningham Falls State Park.  And this is where I continue to research and remain stuck. Supposedly, it was at this time in the 1950’s that the name of Cunningham Falls came about. However, I found an early 20th century postcard that refers to Cunningham’s Falls, but dates to 1908. In any case, I still have not been able to find the “Cunningham” namesake but have heard several possible sources. Some talk of an influential bureaucrat named Cunningham, but no first name or affiliation. Many sources says that Cunningham Falls was named for a photographer, from either Baltimore or nearby Pen Mar Park, who frequently took great pleasure in photographing the falls. Yet, other leads I have been given over time point to a Judge B.A. Cunningham from Frederick, and a Dr. Cunningham from Hagerstown. I give up, and simply like the monikers of Hemann’s Falls or McAfee Falls because we at least know who they were! We may never know the true namesake of Cunningham Falls, but are truly fortunate to have such natural beauty and recreation opportunity here in Frederick County. My boys, however, at this stage of their lives, are more grateful for pancakes and syrup. Of course, I realized this as both Eddie and Vinnie dozed off in the back seat while I was telling them the confusing namesake story of the falls on the way back home after our visit.

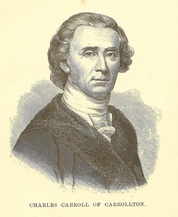

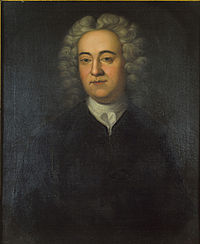

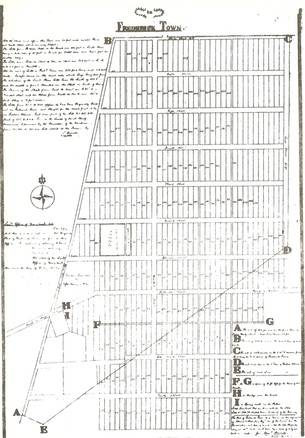

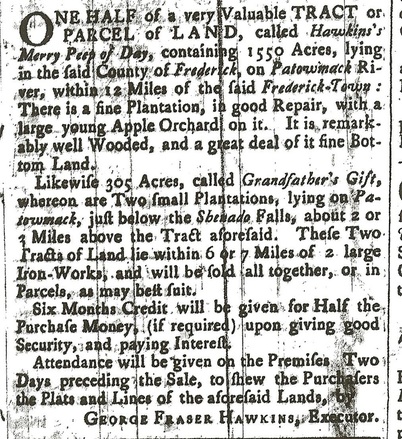

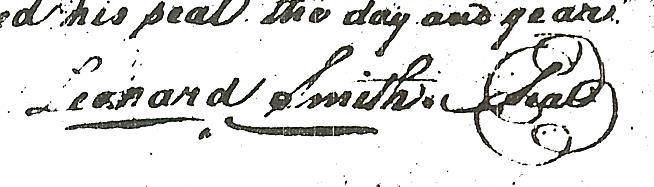

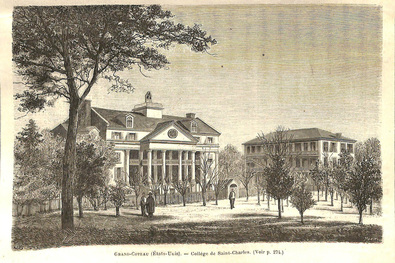

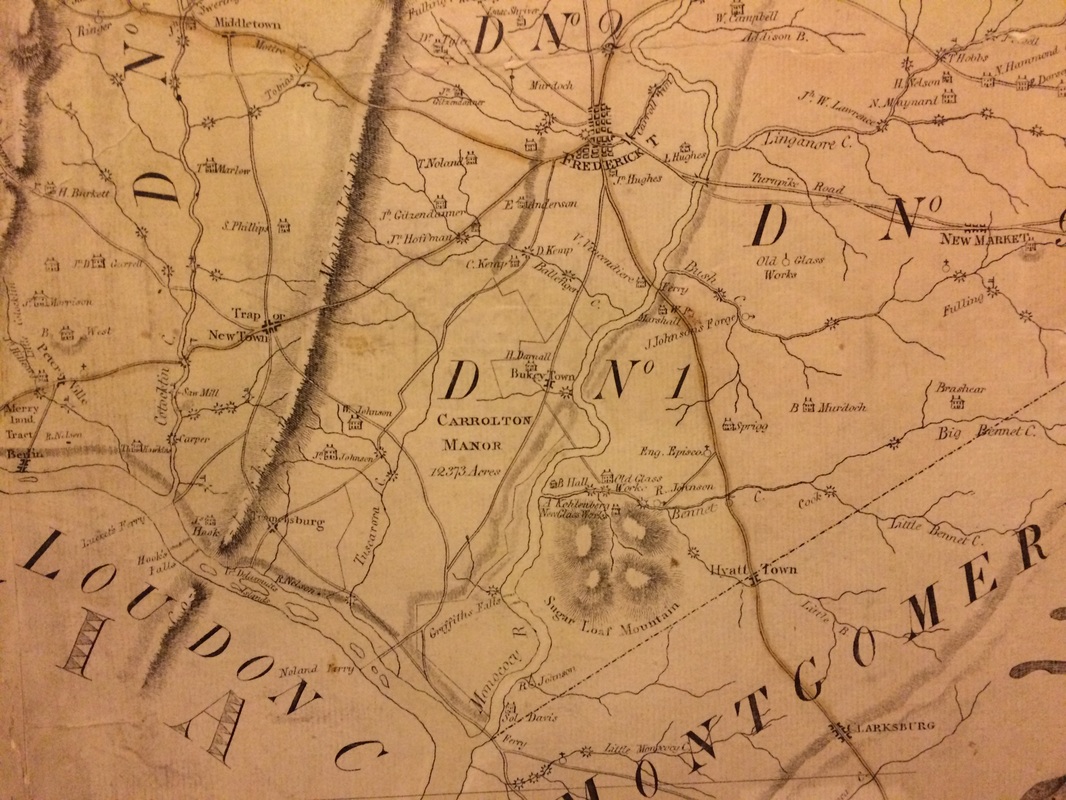

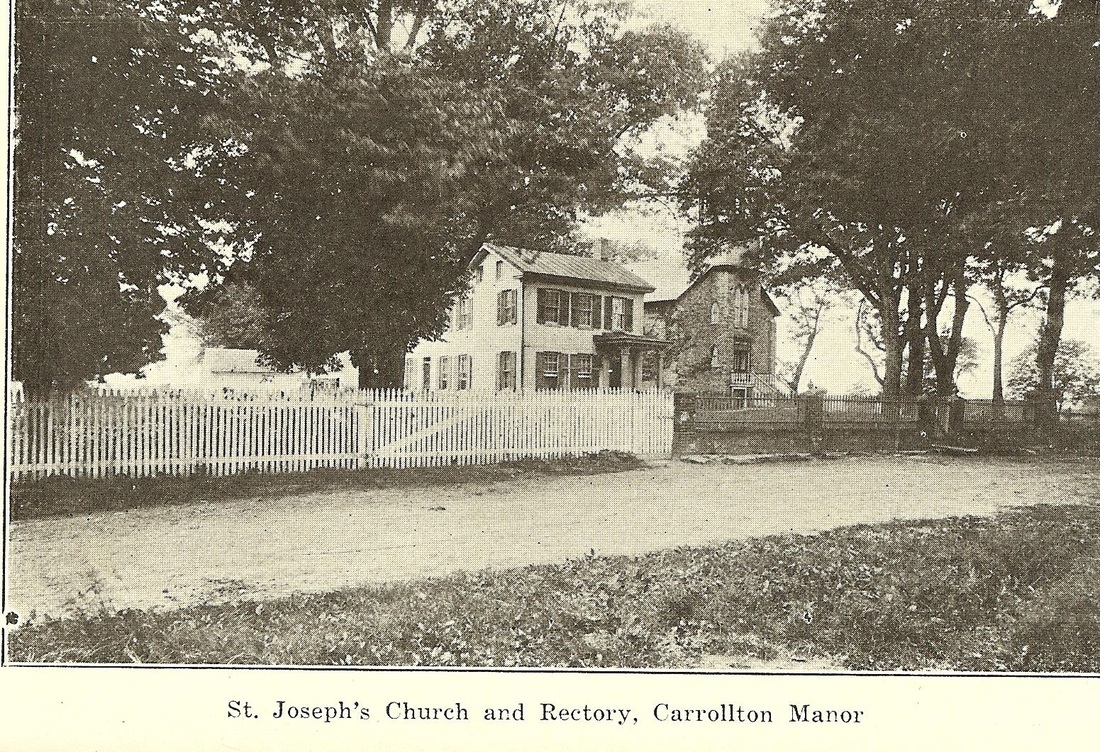

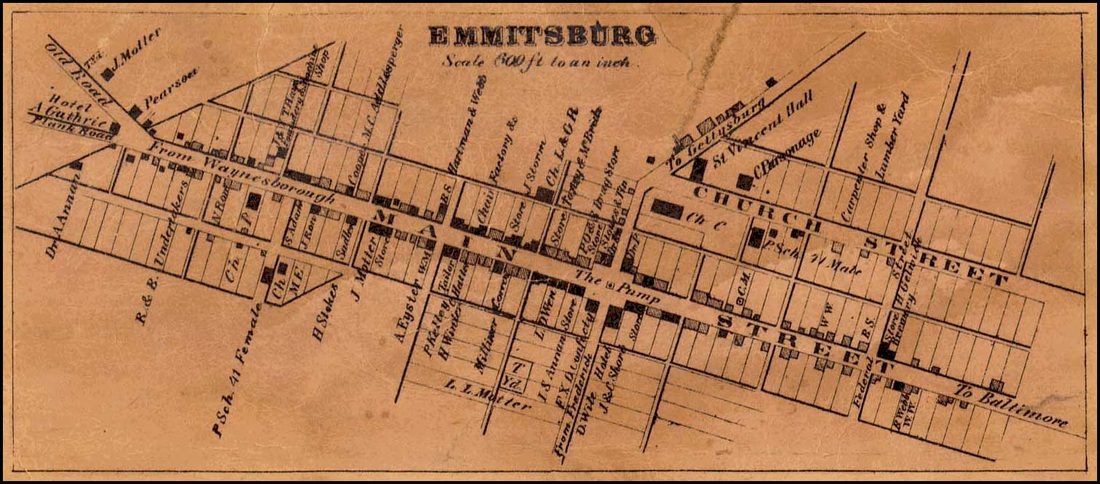

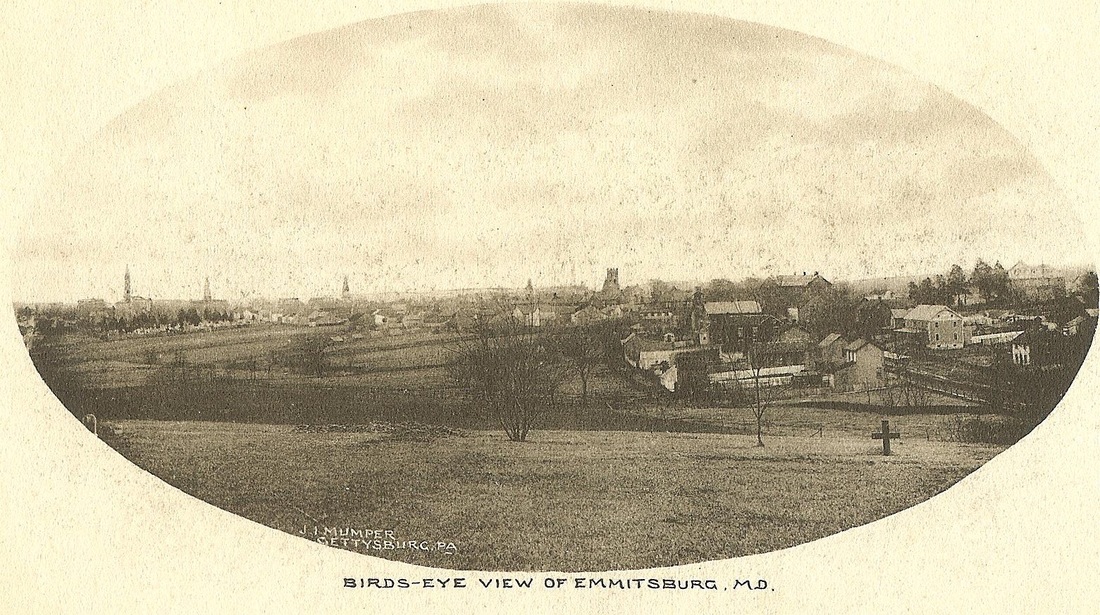

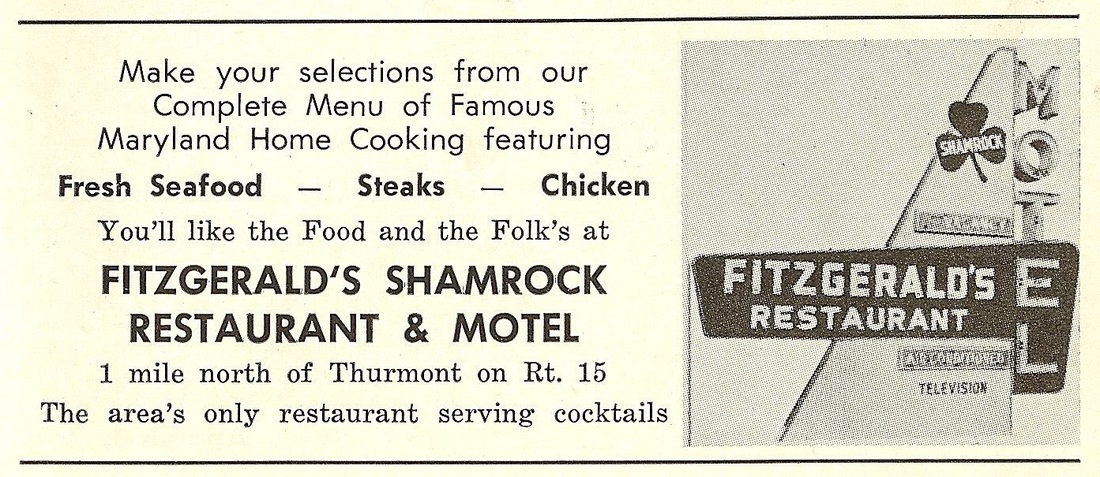

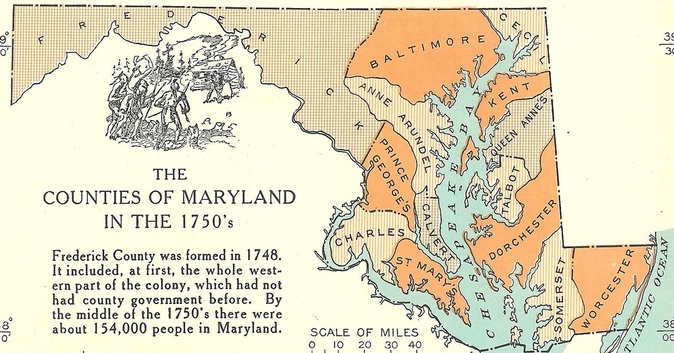

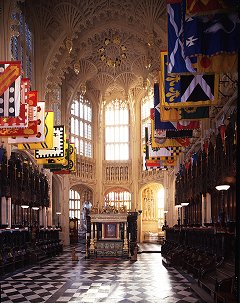

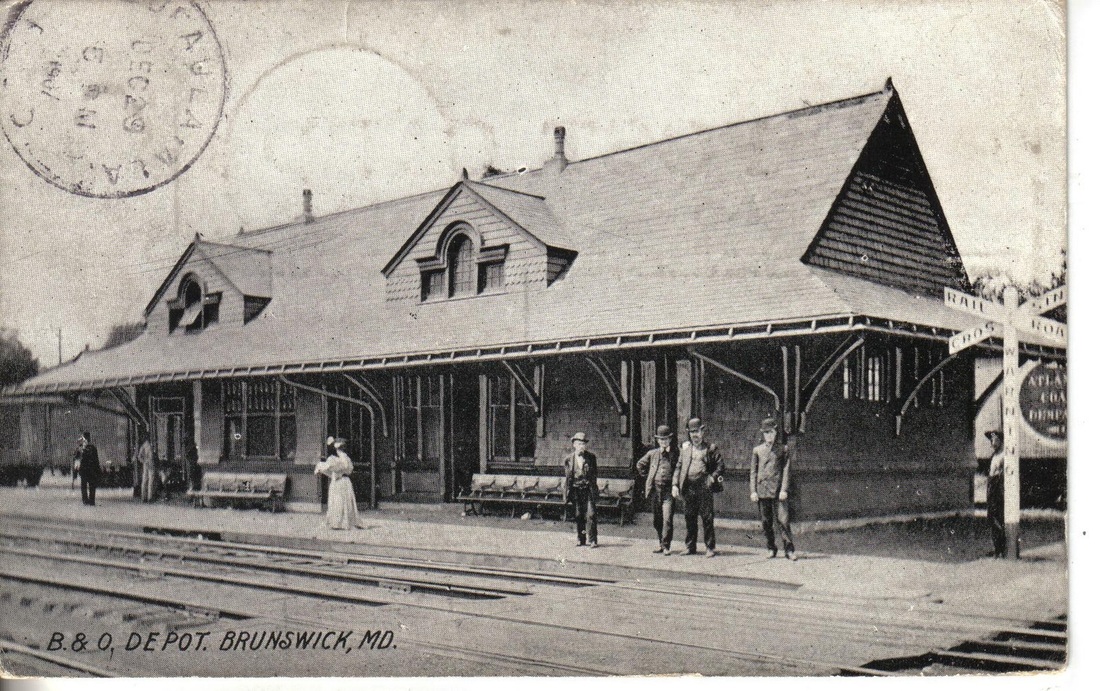

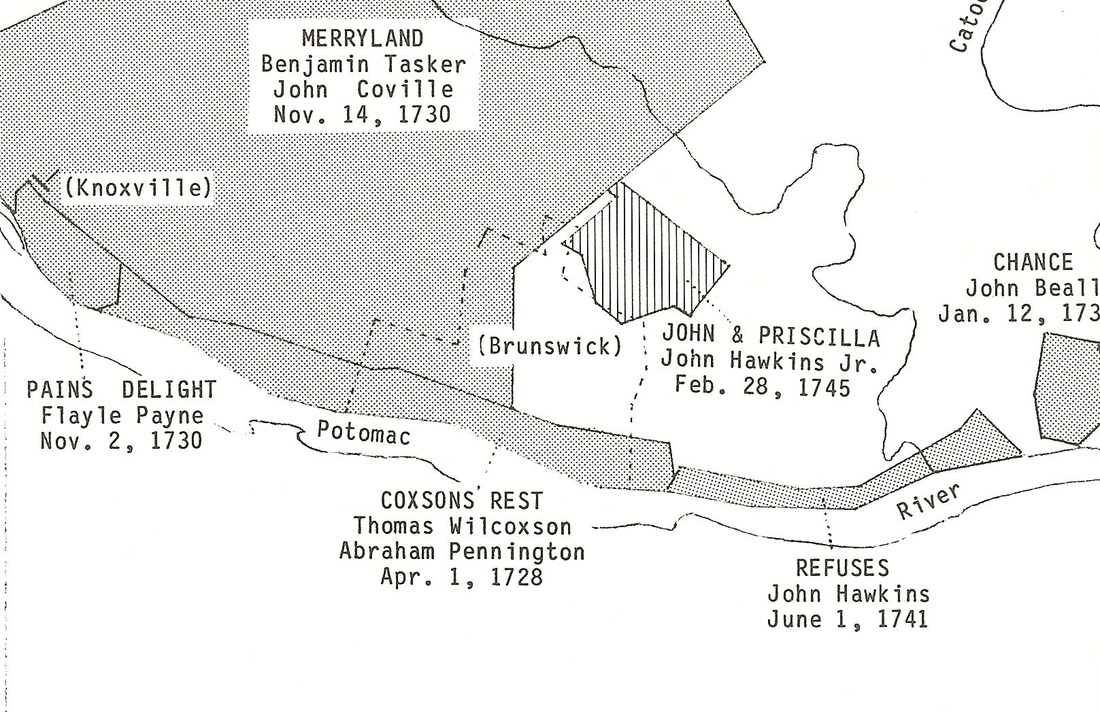

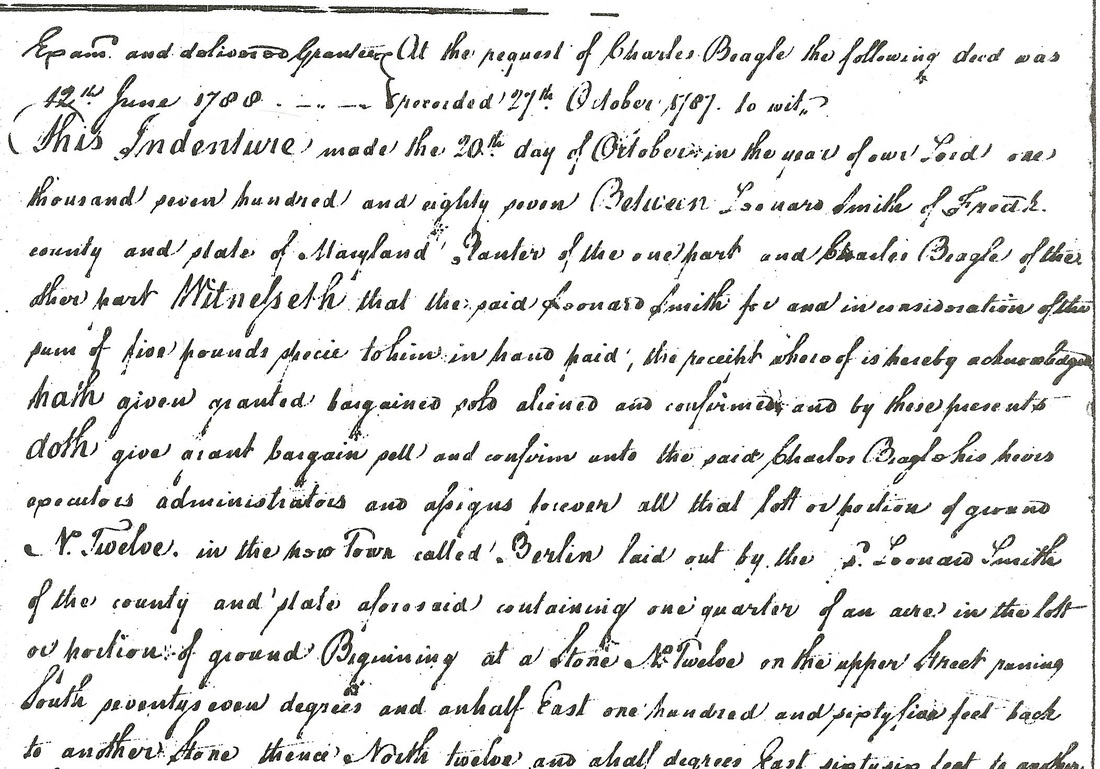

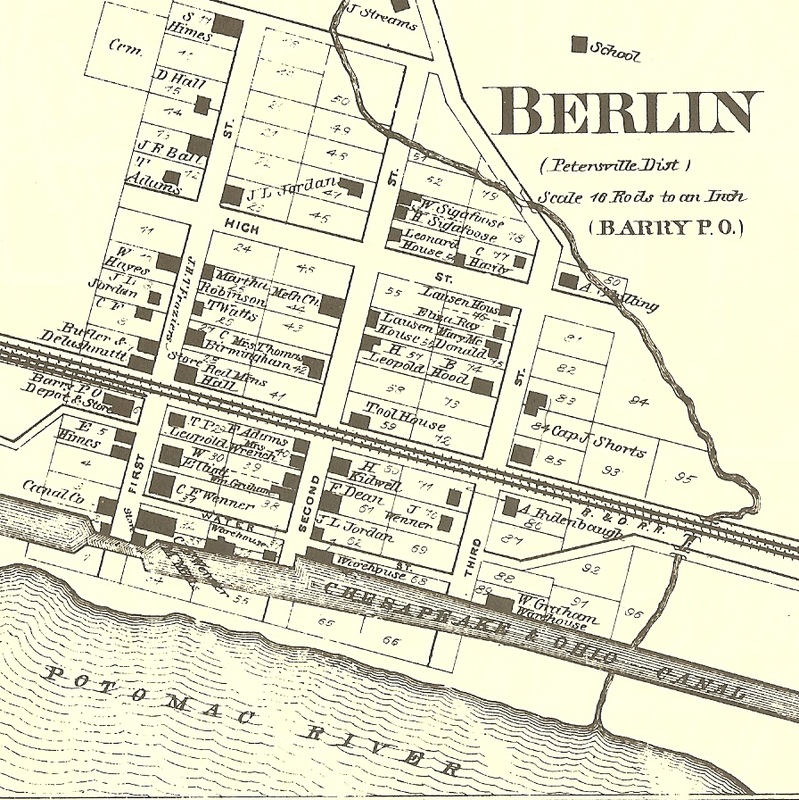

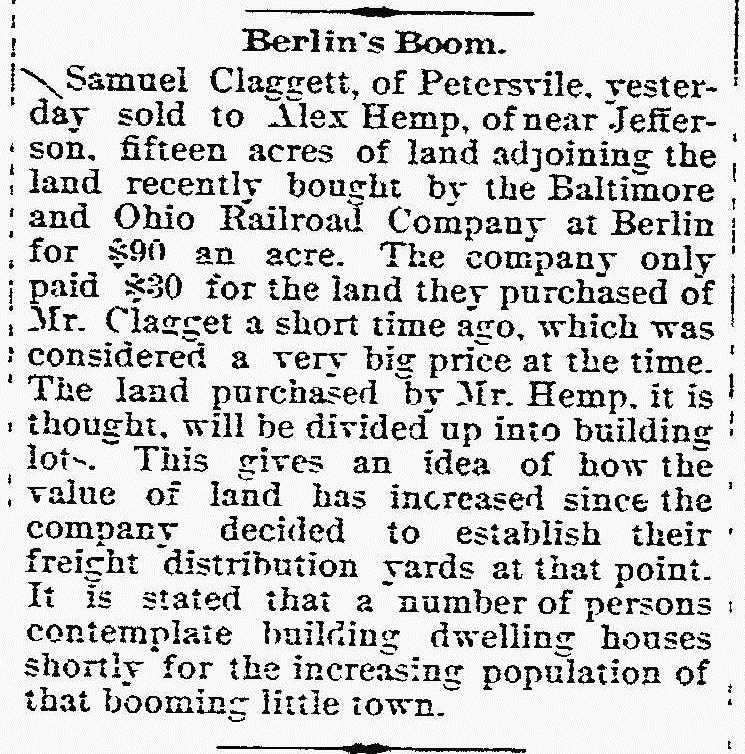

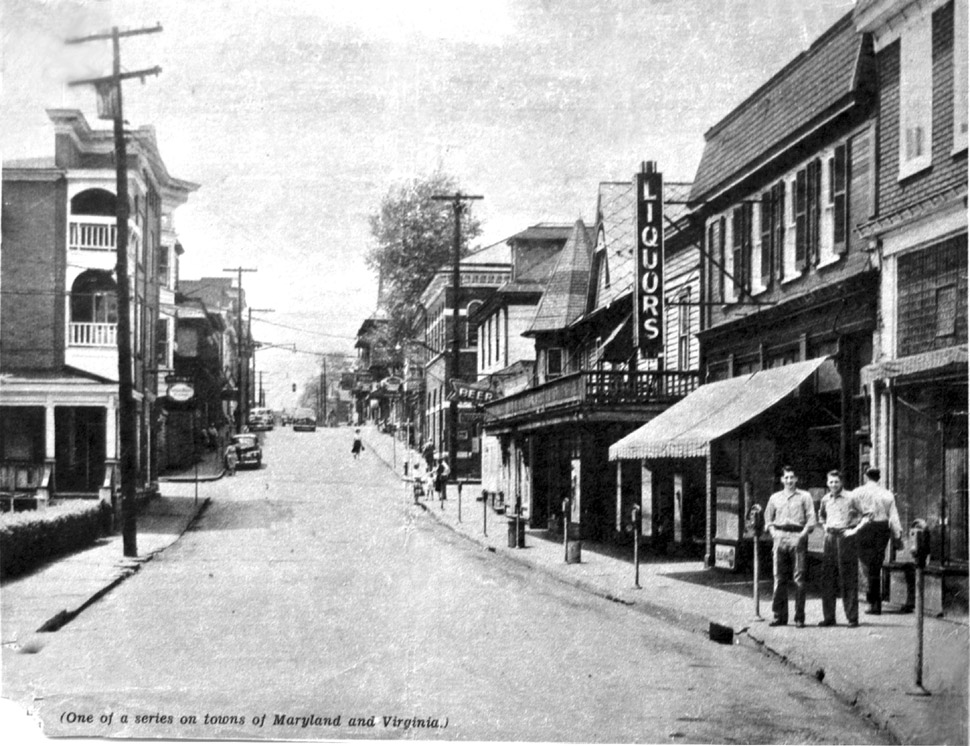

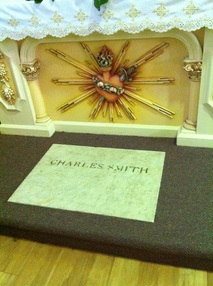

With St. Patrick’s Day upon us once again, I challenged myself to think of obvious, yet non-obvious, places in Frederick County that have been distinctly "Irish" since Frederick’s earliest days. Here’s where our forefathers could have “tied one on” during those colonial era pub crawls I guess. Feel free to add more! Frederick’s Patrick Street Frederick (city and county) can thank an Irishman for their existence. The founder hailed from Queen’s County in the Emerald Isle, coming to America in 1703. When Irishman Daniel Dulany laid out Frederick Town in 1745, he made provisions for two principal streets. The main north-south corridor was named Market Street as the market house and adjacent space would be located here. The main east-west corridor was called St. Patrick’s Street in honor of the founder’s Irish heritage, and this was originally intended by Dulany to be the principal street of town. Its importance would grow as it became part of the important turnpike used for transporting wheat and other products to Ellicott Mills and thus to the Port at Baltimore. It would also become part of the National Road, the first major interior road to the Ohio River Valley and would make travel better for settlers heading west, and travelers heading east. You will find early deeds of Frederick with references to St. Patrick’s Street.  Dr. Patrick Dulany Dr. Patrick Dulany In some histories, it is said that Daniel Dulany named this street after a favorite cousin named Dr. Patrick Dulany, but I find this somewhat doubtful. Who names a place after a cousin, especially one that never visited Frederick Town or America for that matter? Anyway, Dr. Patrick was an alumnus of Trinity College, Dublin, and an eloquent theologian and preacher. He was a close friend to Jonathan Swift, author of “Gulliver’s Travels,” and the man that gave us the term "Liliputians."  Carrollton Manor In 1723, Charles Carroll the Settler (1660-1720) had this 17,000-acre manor surveyed. It takes up a majority of the lower Frederick Valley below the City of Frederick stretching to the Potomac River. Charles Carroll emigrated from Ireland and the County Offally where his family lost much of their land and wealth in the English Civil War (1642-1651) against Great Britain. Unable to serve in local politics because he was Catholic, Carroll gained power and prestige through land acquisition. Multiple heirs would own this parcel which Carroll the Settler claimed was bought originally from the rightful owners, a subgroup of the Tusacarora Indian tribe that had previously lived here from about 1713-1723. This is why we fittingly have Tuscarora High School today in the vicinity. And ironically, the school’s colors include green.  The land conveyed to Charles Carroll the Settler’s son, Charles Carroll of Annapolis (1703-1783), and finally to his son, another Charles Carroll (1737-1832), who took on the place name to differentiate himself from other Charles Carroll’s. It was this “Charles Carroll of Carrollton” who eventually signed the Declaration of Independence, and became a significant leader throughout the American Revolution. Years later, his family built St. Josephs on Carrollton Manor Church and Cemetery in close proximity to their Tuscarora manor house. One tombstone in the churchyard exclaims that it marks a mass grave of over 100 Irish Catholics who perished while constructing the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal and Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. In the early 1820’s & 1830’s the area experienced a calamitous outbreak of Asiatic Cholera which sent many of the Irish workers to their grave. The Irish were plentiful in the creation of both the C&O and B&O. Emmitsburg Speaking of Irish Catholic, you would expect some sort of Irish connection to Emmitsburg. Irish settlers were also prevalent here. Amidst the final resting place of America’s first native born saint, two national shrines and the second oldest Catholic Independent college in the country, there can be found an Irishtown Road. This leads from North Seton Avenue northward over the Mason–Dixon Line and into Pennsylvania. As for Irishtown, it apparently ceases to exist as it would have been located north of Emmitsburg, and likely the spot where a number of Irish families lived in close proximity. As the Boyle family is prevalent here, I’d bet they were one of them. Other early families included the Shields, Harrigans and Callahans. There is an Irishtown about fifteen minutes away and located just north of New Oxford (PA) so you could feed your fix there.  One of the best known Irish families associated with Emmitburg in the last century is the Fitzgerald family. In the 1930’s, they opened a makeshift eatery off their farm property located on the old Gettysburg turnpike (US15). This eventually grew to be known as Fitzgerald’s Restaurant, operated by Allen and Naomi Fitzgerald until 1941. Just over 20 years later, the Fitzgerald’s middle son Donald (better known as “Mike”) and his wife Doris bought a restaurant and club south of Emmitsburg on US15. This joint was formerly known as the Casablanca and located near Franklinville (just north of Thurmont).  In 1963, the couple renamed the business “Fitzgerald’s Shamrock” and it would hold the distinction of being one of the first establishments to serve cocktails in Frederick County. Five sons and four daughters grew up working here, with daughter Donna still operating the business. As the Fitzgeralds gear up once again for their 53rd rendition of the biggest day of the year (St. Patrick’s Day), they won’t have their family patriarch with them. Mike Fitzgerald passed away on February 28, 2016, but I’m sure the remarkable north county businessman will certainly be there (with family and patrons) in spirit. Mike will be attending an even greater St. Patrick’s Day party in heaven, with the patron saint himself! Erin go Bragh! Place names are usually derived from an aesthetic landform or geographical feature. Others can credit an early settler or outstanding citizen. Then there are the locales that have taken their nominal cue from a national icon (such as a president, politician, or war hero) or cultural identity. Lastly, some places are called by names signifying commercial traits. Here in Frederick County we can easily account for names such as Point of Rocks, Thurmont, Burkittsville, Emmitsburg, Jefferson, Garfield, New Market LeGore and Middletown. That leads us to the question of Frederick, both city and county. Why do we have this name, and who is responsible for giving it? At the same time, are there other places out there with this name? All good questions, and looking back in history, it seems that we have a fitting name for a location that has its own special international panache, charisma, rebellious spirit and moxie. However, we may also be named for a scoundrel who suffered from the newly coined ailment of “Affluenza.” It just depends upon whose judgment you trust. Get ready for a “Cliff’s Notes®” version of British royal family history in which you will meet an individual who narrowly missed his chance to make a great impression on world affairs. His grandfather, father and son were British kings, and his great-granddaughter would take the throne at age 18 and ruled for over 63 years, a period known commonly as the Victorian Era. To start the discussion, let’s look at the name meaning of Frederick found as an entry on a website called www.behindthename.com English form of a Germanic name meaning "peaceful ruler", derived from frid "peace" and ric "ruler, power.” This name has long been common in continental Germanic-speaking regions, being borne by rulers of the Holy Roman Empire, Germany, Austria, Scandinavia, and Prussia. Notables among these rulers include the 12th-century Holy Roman Emperor and crusader Frederick I Barbarossa, the 13th-century emperor and patron of the arts Frederick II, and the 18th-century Frederick II of Prussia, known as Frederick the Great. The Normans brought the name to England in the 11th century but it quickly died out. It was reintroduced by the German House of Hanover when they inherited the British throne in 1714.  House of Hanover' arms House of Hanover' arms So what happened in 1714, and more so, what does it have to do with Frederick, Maryland? Well our storied namesake was a complex individual and lived a relatively short, and misunderstood, life. He spent 24 years as heir apparent to the British throne, but would never get his opportunity to rule. Our story can certainly pick up in 1714 with the House of Hanover, a German royal dynasty which once ruled the Duchy of Brunswick-Luneburg, the Kingdom of Hanover, the Kingdom of Great Britain, the Kingdom of Ireland, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It succeeded the House of Stuart as monarchs of Great Britain and Ireland in August 1714 with King George I and held that office until the death of Queen Victoria in 1901.  King George I (1660-1727) King George I (1660-1727) King George I ascended to the throne after the death of Queen Anne (namesake of the Maryland Eastern Shore county bearing her name). This ruler’s reign was brief, 13 years, and trouble- filled as many English subjects thought he was too “German.” Apparently George helped support this notion by spending nearly 1/5 of his reign in his native homeland. He was eventually succeeded by equally “Deutsch” son, George II (1683-1760). King George II married Caroline of Ansbach and the couple would have eight children, with the first born holding the fore-mentioned “peaceful rule” moniker—Frederick Louis (or Lewis). Born February 1st, 1707, the namesake of Frederick, Maryland (city and county) is said to have suffered a lonely and neglected childhood. Frederick Louis’ father (King George II) had a similar upbringing, a victim of his own parents’ bitter divorce. George I is said to have been a cold individual who had several extramarital affairs. When his wife turned to “outside company” in order to fulfill her needs, George I called for the marriage to be dissolved. And that wasn’t the end of it as George II’s mother (Sophia Dorothea of Celle) truly got the raw end of the deal. Her suitor, a Swedish count, mysteriously disappeared (thought to have been tied up with stones and thrown into a river) before an elopement scheme could take place. Queen Sophia would be banished to her castle home back in Germany and held under house arrest for the rest of her life. Worst of all, George I gave strict orders that she was forbidden to see her children ever again. This likely resulted in “unresolved childhood issues” that would manifest in George II’s own ability to parent in the future.  Young Frederick Louis (ca. 1721) Young Frederick Louis (ca. 1721) As for Frederick Louis’ mother (Queen Caroline), she lived with the pain of being orphaned at a young age and was bounced around until becoming the ward of King Frederick I and Queen Sophia Charlotte of Prussia. So it’s easy to have compassion for our namesake, he was somewhat doomed from the start. Frederick Louis was born in Hanover, Germany and was brought up there. He was seven when his grandfather (George I) took the British throne. At this time his parents moved to Great Britain, but left young Frederick back in Germany, where he was given the title of Duke of Edinburgh— becoming the second in line for “the top spot” behind his father. Sadly, Frederick Louis would not see his parents for another 14 years, at which time he was summoned to Britain to take on his new role as Prince of Wales. Throughout that 14-year duration, George I had used Frederick Louis as a pawn against his father (George II). This certainly “primed the pump” for game playing to reach new heights when the spirited 21 year-old Frederick arrived in London in 1728. One of the best descriptions of Frederick Louis comes from noted author and historian Richard Cavendish whose articles regularly appear in History Today magazine (www.historytoday.com): "Open-handed, with an easy manner, he had a certain charm and taste for sport, gambling and women, and though his command of English was uncertain and he looked like a frog, the English on the whole approved of him. The same could not be said of his own family and the hatred between the prince and his parents was a national scandal. What the root of the antipathy really was, no one has ever been able to establish, but Frederick’s father, the king, could seldom bring himself to speak to him and told people that the prince was a changeling and no true child of his. Frederick’s mother once famously described him as ‘the greatest ass and the greatest liar and the greatest canaille and the greatest beast in the whole world’, adding ‘and I heartily wish he were out of it.’ On another occasion, catching sight of the prince from a window, she said, ‘I wish the ground would open this moment and sink the monster to the lowest hole in hell.’ She and his father both preferred Frederick’s younger brother (William), a military hero and Duke of Cumberland. The prince’s demands for more money and his father’s refusal to give it him reached such a pitch that Frederick appealed against the king to parliament, unsuccessfully, for a larger allowance. He regarded his £50,000 a year (at least £3 million/year in today’s money) as miserably inadequate. One reason the prince needed plenty of money was that he ran his own rival court. His persistent political maneuvering against his father’s principal minister, Sir Robert Walpole, was a major cause of offense. When his wife, Augusta of Saxe-Gotha, was about to bear their first child in 1737, Frederick insulted his mother by making sure that she was not present at the birth. The reason she had wanted to be there was to make quite sure that the new arrival actually was Augusta’s child. She doubted very much that it could be Frederick’s and had been telling people that he was impotent."  Daniel Dulany, the Elder (Founder of Frederick Town, Maryland) Daniel Dulany, the Elder (Founder of Frederick Town, Maryland) In 1745, Daniel Dulany the Elder (1685-1753) would strategically use the scorned Prince of Wales’ name for a fledgling town he intended to lay out on land recently obtained from fellow Annapolis land speculator/politician Benjamin Tasker. Dulany started his time in America as an indentured servant, but had studied law and amassed a fortune over a period of four decades. The visionary of Irish blood also held a number of colonial offices over his lifetime. Years earlier, in 1722, he had even written a pamphlet entitled The Right of the Inhabitants of Maryland, to the Benefit of the English Laws, asserting the rights of Marylander's over the Proprietary Government. In his current land speculation scheme, Dulany saw what was occurring in Pennsylvania as proprietor William Penn had experienced great success by “marketing” his Pennsylvania Province (and later Commonwealth) to Quaker and German immigrants looking for a new home in the Americas. The Germans, especially, were a hearty and frugal people bound by religion. They seemed the perfect solution for taming the “wild” interior lands, while also readily possessing high-end tradesman skills to serve their brethren.  Original plat of Frederick Town Original plat of Frederick Town Daniel Dulany’s desire to attract Germans to settle his town (and later county) most certainly lends credence to “Frederick” being a highly attractive name choice. Prince Frederick Louis had remained a favorite among his kinsman, and in 1745 was still heir to the throne once his father passed. Dulany was in the position to have a double victory once King Frederick became a reality. Frederick Town was laid out by 1745, and this constitutes its founding date. Three years later (December 10th, 1748) Frederick County came into being and consisted of today’s Garrett, Allegany, Washington, Montgomery, and most of Carroll counties. Dulany’s planned town became the county seat and prospered tenfold, affording the opportunity for his son Daniel Dulany, the Younger to launch his political career as a representative to the General Assembly. The prominent Annapolis lawyer and land-developer was not the first, however, to use Frederick Louis’ name. A number of other “Fredericks” had their starts in the 1720s and 1730s In 1720, a new county was created in Virginia and named Spotsylvania in tribute to the royal governor Alexander Spotswood. A port town was established eight years later on the Rappahannock River and given the name Fredericksburg. In another part of Virginia, in the Shenandoah Valley, a collection of remote settlements came together in 1738 and became Frederick Town—eventually to be renamed Winchester. The county around this town would eventually take the Frederick name as well, with its first County Court session held on November 11th, 1743. Another example to add to the list is Frederick Township in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, a quiet countryside that received its official name and government in 1731. Here in Maryland, Prince Frederick became the new county seat of Calvert County in 1722 thanks to an Act of the Maryland General Assembly. Across the Chesapeake Bay and to the north, Fredericktown was laid out in Cecil County on December 11th, 1736. It was previously known as Pennington’s Point, named for the family of a noted Indian trader, Abraham Pennington. Pennington was the first permanent European settler to reside in what would become Frederick County in the vicinity of today’s Brunswick—in name, at least, representing another connection to Prince Frederick and the House of Hanover.  Augusta of Saxe-Gotha, wife of Prince Frederick Louis (1719-1772) Augusta of Saxe-Gotha, wife of Prince Frederick Louis (1719-1772) Let’s get back to Prince Frederick Louis. What can be said of him was that he was a decent family man. He married 16 year-old Augusta of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg and had nine children. History records that he was a much better father to his kids than his own father had been to him. Interested in the arts, Frederick collected pictures, wrote songs and poetry, played the cello well and loved music. He was also an enthusiast for hunting, shooting and fishing, and captained the Surrey cricket team for several seasons. Unfortunately the latter could have led to his demise. In 1751, Prince Frederick allegedly suffered a blow to his chest from either a cricket ball or tennis ball, causing an abscess. Although this story may be apocryphal, Frederick Louis died of pneumonia shortly thereafter on March 31, 1751. Some historians contend that this could have been a likely complication that arose from a freak injury of the sort.  "Poor Fred" (1707-1751) "Poor Fred" (1707-1751) Sadly, Prince Frederick Louis would never claim the throne. His father died in 1760, but the heir would be George III, Frederick Louis’ eldest son. Our namesake Frederick was buried in Westminster Abbey, in the Henry VII Chapel, with a minimum of ceremony and without a single member of the royal family present. His epitaph is far better known then he is: HERE lies Fred, Who was alive and is dead. Had it been his father, I had much rather: Had it been his brother, Still better than another: Had it been his sister No one would have missed her: Had it been the whole generation, So much the better for the nation, But since ’tis only Fred, Who was alive and is dead, Why there’s no more to be said.  King George III (1738-1820) King George III (1738-1820) George III would “Rule Britannia!” through the American Revolution and War of 1812 (1760-1820). It’s interesting to ponder if the king ever ran across the name of Frederick (city or county), Maryland? We gave ample opportunities with patriotic events and personages such as the 1765 Stamp Act Repudiation, support of the people of Boston during the American Revolution blockade, the Star-Spangled Banner by Francis Scott Key, Thomas Johnson, Jr. (first elected Maryland governor), and John Hanson (president of Congress under the Articles of Confederation). Later on, during the American Civil War, the immortal line ‘the clustered spires of Frederick Town’ could have rolled off the lips of Prince Frederick Louis’s great-granddaughter, Queen Victoria. Thanks to John Greenleaf Whittier’s poem Barbara Frietchie, the town won international fame and made its way into British schools and back to Frederick Louis’ homeland of Germany because of the heritage of the poem's heroine. When one commonly thinks of Brunswick, Maryland today, they likely envision a peaceful town, steeped” (both literally and figuratively) in railroading history, baseball, and plenty of outdoor recreational opportunities tied to the Potomac River and adjacent C & O (Chesapeake & Ohio) Canal towpath. Today’s solitude is a deep throwback to a much earlier time in the area’s existence, before its amazing transfiguration into a bustling transportation corridor for almost 250 years. Roots stretch back to 1728, when Indian trader Abraham Pennington operated his post on a tract named “Coxson’s Rest,” near the location of today’s Lock 30 (of the canal). This was a narrow, riverfront property stretching nearly three miles along the Potomac and one mile inland. Other frontiersman and government officials simply called this place Pennington’s, as it was a lone beacon amidst a vast wilderness environ of marshy mud flats, not unlike the famed bayou country of Louisiana. In the preceding few decades, the shores from current day Brunswick to the Monocacy Aqueduct served home to settlements of the Tuscarora and Piscataway native peoples. During this habitation, earlier place names for Pennington’s vicinity were based on memorable animals-in-residence—“Eel Pot Flats” and “Buffalo Wallows.”  Maryland Gazette (August 1, 1765) article announcing sale of Hawkin's Merry Peep O' Day by George Fraser Hawkins (son of John Hawkin's Jr.) Maryland Gazette (August 1, 1765) article announcing sale of Hawkin's Merry Peep O' Day by George Fraser Hawkins (son of John Hawkin's Jr.) The geographic area that would eventually become Frederick County (but not until 1748) was getting noticed by powerful land speculators from the long established southern portion of the colony. Abraham Pennington, born in Cecil County ca. 1670, had devised a water ferry at Coxson’s Rest. This would launch a long line of ferry operators, including a wealthy native southern Marylander by the name of John Hawkins, Sr. (1713-1758). Hawkin’s took the reigns from Pennington when the latter departed for Virginia, eventually dying in South Carolina in 1756. This shallow, portage spot to the Virginia colony became the “Chesapeake Bay Bridge” of its day. The importance of place was recognized by adventurous early European settlers heading south and westward as “German Crossing” and “Potomac Crossing.” In 1753, the aforementioned John Hawkins, Jr. supposedly received a grant of 3,100 acres in the southernmost eastern tip of Middletown Valley from King George II of England. Another colorful name would abound for the Brunswick area as the grant went by the name “Hawkins’ Merry Peep O’ Day.” Having nothing to do with marshmallow candy whatsoever, this land title is said to have derived from the romantic image of an early morning sunrise view looking eastward from this vantage point, with the sun gradually “peeping” over Catoctin Mountain. John Hawkins, Jr. died in 1758 and his property was conveyed to his sons. The property sifted through multiple owners, as did the popular ferry. One of the interesting owners of this period was a man named Christian Slimmer who operated from the Virginia shore on lands formerly owned by British Parliament member Charles Bennet, 3rd Earl of Tankerville (1716-1767). In 1778, Slimmer had received his license from the Virginia legislature to operate his aptly named “Tankerville Ferry” to the Maryland side. In the process, the area is said to have taken on the name of Tankerville for a duration.  A 200 acre section of Hawkin’s “Merry Peep O’ Day” property would eventually wind up in the hands of Leonard Smith in 1780. Smith can be linked through his mother’s side to his namesake Leonard Calvert, first governor of the Maryland colony. He likely came to Frederick County in the 1750’s from Charles County, but was born in St. Mary’s County, Maryland in 1732. He likely was living on Carrollton Manor as his wife was related to the Carroll and Davis families. In the fall of 1774, Leonard Smith laid out “New Town” for a widow named Eleanor (Combs) Medley. Leonard Smith sold a large number of these lots the day after widow Medley died in January 1775, with the first lot going to his brother-in-law Charles Neale. “New Town” would soon wear the name of Newtown Trap, Traptown and simply Trappe because it earned the reputation of being a “very tough place,” where travelers were often waylaid and assaulted and “sometimes foully put out of the way.” In 1831-32, Newtown Trap was incorporated and received the new name of Jefferson. Not too much else is really known about Leonard Smith. He was married to Elizabeth Neale, a great-granddaughter of Captain James Neale (1615-1684) of "Wollaston Manor" (an early Maryland land grant bequeathed by the Crown in 1642). The Smith and Neale families were among Maryland’s early Catholic gentry, land were large plantation owners that utilized slave labor. Leonard Smith, like others of his pedigree, saw opportunity for investment and prestige in the fledgling Frederick County. During the American Revolution, Smith served with other “men of mark” who had come to Frederick with similar aspirations. He served on the committees of Safety and Observation for Frederick County with great patriots such as Thomas Johnson, Jr. John Hanson and Dr. Philip Thomas. Leonard’s son Captain John Smith (1754-1805) served with distinction in Maryland’s Flying Camp. In 1780 Leonard Smith now used a part of his acreage to establish the small town that eventually became known as Brunswick. By 1787, he had surveyed ninety-six lots and gave the place a new name, “Berlin.” This was most likely done to attract Germans settlers, many of which had been passing through for over five decades en route to Virginia, the Shenandoah Valley and points west such as the land destined one day to become Kentucky. Smith sold at least forty-seven of these lots before his death in 1794. His descendants eventually sold the remaining lots. Thanks to its location near the river, Berlin soon became a small trading center, boasting a flouring mill and carrying on trade with the surrounding farms in the area, not to mention Virginia neighbors across the river and the inhabitants of nearby Harpers Ferry, home to the United States Arsenal.  Letter sent from Barry, Maryland, dated June 30th, 1849 Letter sent from Barry, Maryland, dated June 30th, 1849 Berlin grew large enough to warrant a post office in the year 1832. At this time, the town was christened with a new name, “Barry.” The change was made to avoid confusion with the town of Berlin found in Worcester County, just inland from Ocean City. The townspeople were not impressed and went on referring to their town as Berlin, but accepted Barry as the name for the post office.  Exciting times were on the horizon because in 1834, two new travel innovations would come through town along the river’s edge. Berlin first and foremost became a bustling “canal town” as the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal connected it with Georgetown and the nation’s capital. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad would have its rails here, but was more of a pass through than anything else. That would certainly change as the century progressed. In subsequent years, warehouses would be built and service industries catered to the canallers, meanwhile, Berlin was enduring land grabs of “right of ways” by the two transportation giants, only to be followed with skirmish raids by Confederates from across the river during the American Civil War. In fact, a wooden covered bridge across the Potomac was destroyed in 1861, just two years after its construction—quite a blow. After the Battle of Antietam, the Union Army used Berlin as a major supply depot due to its pivotal location, and was forced to construct a pontoon bridge to move troops and materials across the river into Virginia.  Tensions eventually waned, and the town was eyed to play a larger role for the B&O. In 1890, the railroad decided to move its extensive freight yard operation from Martinsburg, West Virginia, to Berlin. The boomtown phenomenon took hold and a population of 300 in 1890 would soar to 2,471 in 1900, and over 5,000 inhabitants by 1910. Brunswick and its new housing sprawled over the adjacent hills (Wenner’s Hill, New York Hill, Fitzgerald’s Hill, Brick Yard Hill and Sandy Hook Hill). This time around the railroad would be more stringent than the post office. A name change was necessary to keep passengers and freight from going to the wrong Berlin, Maryland. An act of legislature on April 8, 1890 changed the town’s name yet again. This time it became Brunswick. On the bright side, the act officially incorporated the town and instituted the current mayor and city council form of government. It also established town boundaries. However, more bad news came for many citizens as the act prohibited the sale of liquor. The railroad truly shaped the town in its own image for the better part of the 20th century. This gave rise to the unofficial name of “Smoketown” for Brunswick. And from there, as they say, the rest is history. Today, Brunswick is a “Main Street Maryland” community, boasting several shops and eateries to go with its amazing transportation heritage story. A revitalized, historic downtown center and array of special events such as the annual “Railroad days” celebration beckons visitors from near and far.  Grave of Leonard Smith in St. John's Catholic Cemetery (Frederick, MD) Grave of Leonard Smith in St. John's Catholic Cemetery (Frederick, MD) But what can be said of the town’s founder, Leonard Smith? He could have applied his own name, “Smithtown” to the vicinity, but he didn’t. Smith died in 1794, while his Berlin was still in its infancy. He would originally be laid to rest in Frederick City’s Jesuit Novitiate grounds. Today, an impressive monument can be found over his mortal remains in St. John’s Cemetery. Interestingly, Smith is really nothing more than a footnote today, as no statues or street names immortalize him in either Brunswick or Jefferson, the town’s he put into being. However, his children and descendants are remembered for their roles with the family’s beloved Catholic Church. Smith’s daughter Jane (1774-1841) would join Elizabeth Ann Seton’s Daughters of Charity in Emmitsburg, taking the name of Sister Mary Joanna. She is buried in the historic cemetery on the Seton Shrine grounds.  St. Charles College in Grand Coteau, Louisiana St. Charles College in Grand Coteau, Louisiana Three of Leonard Smith’s sons actually sojourned to authentic bayou country—Louisiana. Following their father’s death, Charles, Benjamin and Raphael Smith went to the vicinity of Grand Coteau, St. Landry Parish (located midway between Opelousas and Lafayette, Louisiana). The brothers became large plantation owners and Charles Smith, in particular, made the greatest contribution to the area. In 1819, he donated several parcels of land to be used for a cluster of various church structures, giving shape and purpose to the little community. Out of this would come St. Charles Borromeo Church and grounds, plus generous expanses of property in 1821 that would provide pastoral settings for the Academy of the Sacred Heart and in 1837, St. Charles College (now a Jesuit seminary and retreat house). These were purposefully named in Charles honor, and so was the town as it was originally called St. Charles Town before being changed to Grand Coteau. Grand Coteau is derived from French, meaning “great hill.” I guess this opens the door for yet another possible name change for Brunswick in the future, as it is a city built upon a great hill, isn’t it? Just an idea. (AUTHOR'S NOTE: FaceBook’s “Smoketown History (Brunswick, MD)” page by Clay Thomas & Nancy Merchant Langley is a terrific site for town heritage stories, photos and reminiscing of yesteryear). Also be sure to check out the Brunswick Heritage Museum. Thanks also to Brunswick Main Street's website for a few of the vintage images.

|

AuthorChris Haugh Archives

February 2024

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed