HSP HISTORY Blog |

Interesting Frederick, Maryland tidbits and musings .

|

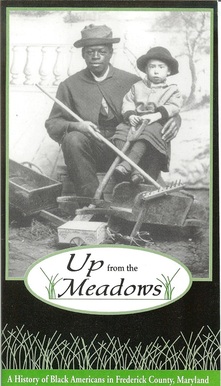

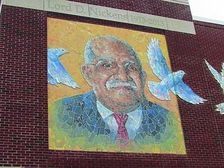

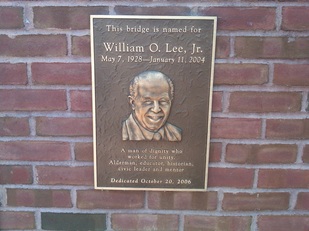

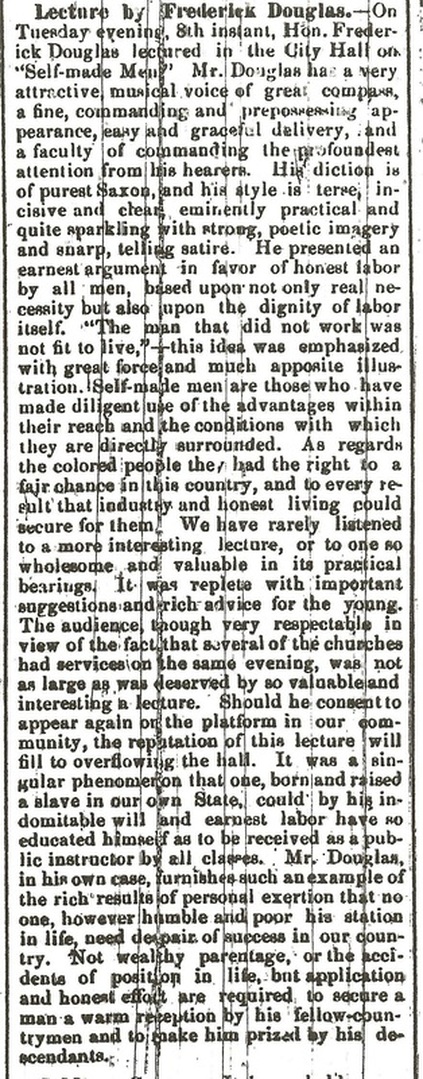

I just enjoyed an interesting past week of reminiscing. It was 20 years ago (February 1996) that I embarked on a video documentary project focusing on the black history of Frederick County, Maryland. A little over two years later (March 1998), I found myself on a stage in San Diego, California accepting an award called the Beacon Award of Excellence, the highest honor for communications and public affairs in the Cable Television industry. It was quite a thrill, but more so, a humbling experience as this award belonged to my many "teachers" for this endeavor, along with a host of people I only knew as gravestones, sprinkled throughout the county. Their spirits were certainly guiding me. The five-hour documentary was given the title “Up From the Meadows,” a play on the opening line from John Greenleaf Whittier’s famed poem about hometown Civil War heroine Barbara Fritchie. Throughout the production process, I was able to live in the moment, as I knew that creating this long-form television program would not only educate and humble me (a white male born at the tail-end the Civil Rights Movement period) but it would shape my thinking about past events, places and persons. I went into the project with the basic black history knowledge I had carried since my childhood and early school days. There were the obvious stories of Martin Luther King, Rosa Parks, George Washington Carver and Jackie Robinson. I also could make connections to my home state through legendary native Marylanders: Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, Benjamin Banneker and Thurgood Marshall. When I was 10 years old, my parents encouraged me to watch the “Roots” television miniseries, which premiered in 1977. Like countless other Americans, black or white, I became inspired toward a lifetime search to know my own ancestors. However, the greater takeaway was getting my first glimpse of a dramatization of the African slave trade and slavery in from Colonial America up through the American Civil War, and continued prejudice and segregation that would permeate society in the century to follow. It made quite an impression. From time to time, I thought about delving into a black history of Frederick, and was inadvertently pushed over the threshold by the late Dr. Len Latkovski, beloved professor of history and political science for Hood College. I had utilized Len as an on-screen commentator for an earlier Frederick City history documentary I began producing in 1993. The seasoned professor, originally from Latvia, amazed me with population statistics and anecdotes relating to Frederick County’s slave and free black populations. He also encouraged me to look at slavery through the lens of different religions and their views on slavery (particularly Catholicism, Methodism and the Society of Friends). Len made me realize that Frederick County’s past made for a unique case study of the African-American experience. Where else could you find such a great number of free and enslaved black people living in the same environs—a place bordered by the Mason-Dixon Line to our north, and the Potomac and Virginia, capital of the Confederacy to our south. And all this set in motion and dictated by the original white European cultural settlement patterns of Frederick County. I would zero in on this “border county within a border state” notion as a central tenet of this proposed “black history” documentary. My experiences with “Up From the Meadows” have been readily coming to mind over the past month. I’ve been preparing lectures and readying materials for an upcoming, multi-week class on the subject as I’m slated to teach a course (in March and April) for Frederick Community College’s Institute for Learning in Retirement (ILR) program. The students and I will view portions of the documentary, interspersed with me explaining the production process, and discussing pertinent points of subject matter. Simply put, the two-part, six session class will be “chock-full” of historic events, places and people from Frederick County’s past that have hovered “below the proverbial radar.” And for a story this rich and important, I can’t say I will be teaching alone. I will have a host of on-screen instructors helping me out, just as they had back in May 1997 with the program’s premiere on cable television.  Dr. Blanche Bourne-Tyree Dr. Blanche Bourne-Tyree One of these “teachers” is Blanche Bourne Tyree, who holds the distinction of being the first woman from Frederick County to have earned a medical degree. She had a successful career as a pediatrician and a public health administrator for over 40 years. In retirement, she has built an impressive resume of civic involvement, including a three-year stint as co-host of “Young at Heart: Frederick County Seniors Magazine,” a program I proudly oversaw as executive producer while at GS Communications. Medicine would certainly define Blanche Bourne Tyree’s immediate family’s life. Her father was a man named Dr. Ulysses Grant Bourne, Frederick’s first black physician. Dr. U.G. Bourne hailed from Calvert County, and came to segregated Frederick in 1903, after completing his education in North Carolina at Leonard Medical College. Despite being allowed to practice at Frederick Memorial Hospital, Dr. Bourne went on to open a 15-bed hospital for blacks on West All Saints Street in 1919. This would be the first county hospital to accept patients of color. Dr. Bourne was a magnificent civic leader as well whose many accomplishments include the founding the Maryland Negro Medical Society and co-founding Frederick’s NAACP chapter. His name now adorns the Frederick County Government building formerly known as the Montevue Assisted Living Facility (located on Montevue Lane.) His other two children experienced success in the healthcare field as well. Dr. Ulysses Grant Bourne Jr. became the first black doctor to have privileges at Frederick Memorial Hospital, while daughter Gladys (Bourne) Thornton became a nurse. As snow and freezing rain fell outside, I visited Blanche at a local nursing home. The 98 year-old had been plagued by recent setbacks which precipitated this stay away from her Crestwood Village home. I thought about how surreal this must feel for her, a veteran physician and caretaker herself, now finding herself firmly in the role of patient. As I sat in awe of my beautiful friend, discussion on that morning included our past documentary and the day of our interview taping, one in which we were forced to “shoo” her late husband Chris (Tyree) out of the room we were using because he was interjecting too many comments from the “peanut gallery.” We also recalled one of the true highlights of my professional career, something that began as a simple invitation Blanche had given me. This was in the early spring of 1998, and featured a road trip to find Blanche’s father’s original homestead and farm in lower Calvert County. I did the driving and along the way, we picked up Blanche’s cousin who would help guide us to the rural vicinity of Island Creek (near Broomes Island), where Blanche’s grandfather Lewis Bourne and wife Emily raised their ten children in a small rural Black settlement in the decades immediately following the Civil War. The old family house had been boarded up for several years, slowly decaying into the surrounding landscape. I did, however, feel the importance of place here— having produced two generations of Bournes that would certainly shape Frederick into the great place we know today. With last week’s visit, I again had the opportunity to thank Blanche for her assistance and friendship over the years, but especially with this project. She is my lone, surviving on-camera commentator from the program which originally boasted 12 Frederick residents. It was moments such as the trip to Calvert County that helped give me a better understanding of black history and legacy in Maryland, and of my home county in particular. As a white male, I will never be able to fully understand, but with this priceless tutelage, I was able to position myself as a conduit, relaying experiences from residents like Blanche who truly “lived” the documentary.  Lord Nickens Memorial Mural (Frederick, MD) Lord Nickens Memorial Mural (Frederick, MD) Dr. U.G. Bourne was the father of one of my interview subjects, and mentor to another. Lord Dunmore Nickens (1913-2013) was truly influenced by Blanche’s dad, propelling him to take the lead in civil rights activism for the better part of his 99 years. Mr. Nickens taught me a great deal as well, and shared a myriad of personal experiences, “fighting the good fight,” on tape with me. He passed away just over three years ago, but not before being honored with having a street in Frederick named after him. In 2014, a mosaic memorial mural depicting Mr. Nickens was unveiled on the side of a downtown building located at the corner of North Market and Lord Nickens streets.  Plaque honoring William O. Lee (1928-2004) adjacent Frederick's "Unity Bridge" in Carroll Creek Park Plaque honoring William O. Lee (1928-2004) adjacent Frederick's "Unity Bridge" in Carroll Creek Park Another “Up From the Meadows” alum was memorialized with a decorative suspension bridge crossing Carroll Creek. William O. Lee is best remembered as a longtime educator, municipal politician and community activist. This “gentle man” in the highest regard, can be credited as being among the first people to chronicle and promote Frederick City’s black heritage, highlighted by his childhood home of the All Saints neighborhood as the central hub for black life for well over a century. He walked me all over town, working hard to make sure I had a firm understanding of Frederick’s foremost endeavors in education, business, charity and social life in the segregated black community and how barriers were finally chipped away in an effort to unite two Frederick’s into one—figuratively “bridging the town creek.”  Grave of Kathleen (Dorsey) Snowden (1933-2008) at Simpson Christian Community Church (New Market, MD) Grave of Kathleen (Dorsey) Snowden (1933-2008) at Simpson Christian Community Church (New Market, MD) What Bill Lee taught me about the city, Kathleen Snowden of New Market taught me on the county level. The self-proclaimed “outspoken” New Market resident shared her knowledge, based on years of intensive black history research. Ms. Snowden accompanied me as travel companion on several field trips. We searched for the remaining traces of former “black sections” of leading towns (ie: Middletown, Brunswick, Libertytown) and explored “post-emancipation hamlets,” places like Sunnyside, Bartonsville, Della, Hope Hill and Coatesville. In addition, we experienced black churches together, looked for old colored schoolhouses and walked countless black burial grounds, seeing names in stone of former slaves and descendants of slaves, not to mention those of soldiers and prominent early free blacks who lead their neighbors in the long fight towards equality.  Marie Anne Erickson (1932-2011) Marie Anne Erickson (1932-2011) Other teachers for me included 100 year-old Ardella Young of Pleasant View, Maude Morrison, Luther Holland, Arnold Delauter, Bessie Brown, Edith Jackson, Henry Brown and a lone, yet powerful white voice—Marie Anne Erickson. Marie taught me to embrace the fact that I was incapable of appreciating or fully understanding what my other subjects and the black population (past or present) had experienced over their lifetimes. I was white, and male to boot, the long dominant power combination in our country since its inception. I had not experienced struggle of any kind. Marie Erickson was born and raised in Illinois, the daughter of Swedish immigrants who immigrated to the US in 1923. She would die in 2012, but not after four decades of assisting local Frederick blacks research their roots, and gaining family connections. Marie was not only a friend to so many people of color, but became accepted as an “honorary” family member in many instances. All the while, she remained 100% genuine, not simply showboating for self-gain. Marie cared about equality and often looked for “teachable moments,” objects and opportunities in which to share illustrative “black” stories and experiences with white and black readers alike. These appeared through her countless articles and letters to the editor in Frederick newspapers and magazines. As I said earlier, using Frederick County and its past for context, serves an amazing canvas to tell this story, introducing individuals such as William Ware, Elijah Lett, Professor James Neale, Decatur Dorsey, John W. Bruner and places like Oldfields, Centerville and Halltown. Current residents such as Joy Hall Onley and members of Frederick County's AARCH group (African American Resources Culture and History) continue their amazing work of "piecing together" and preserving this rich legacy. Meanwhile, I’m happy to report that Black History Month will be extended through March and April this year for those individuals who take a two part, six class, “Up From the Meadows” course from Frederick Community College. While the course catalog says it’s my class, I think you can see that I will have plenty of help from former friends and mentors—the true legends who helped research, preserve and make Frederick County history.

For additional information, visit: http://ilratfcc.com/portfolio/up-from-the-meadows/

16 Comments

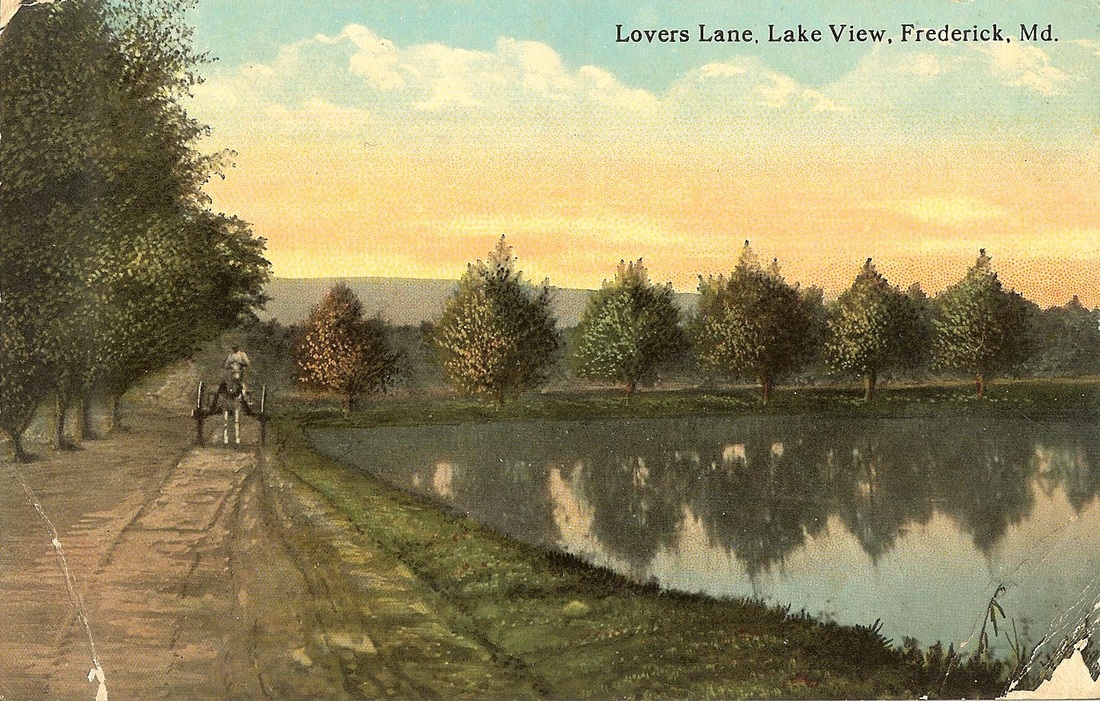

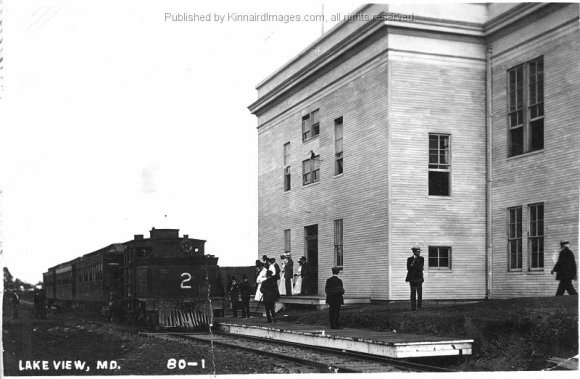

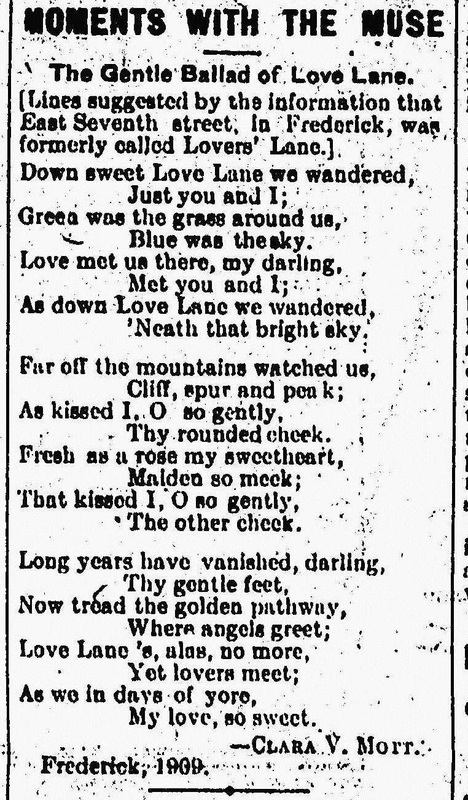

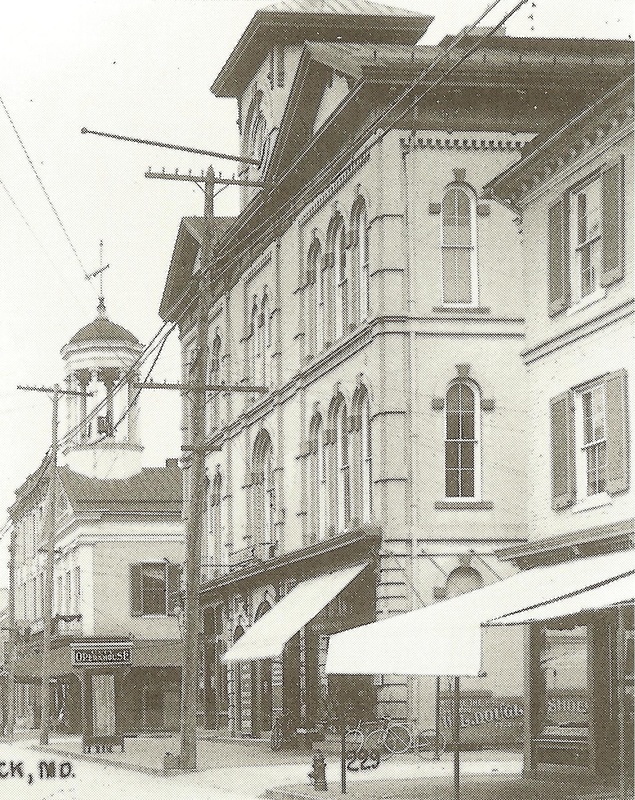

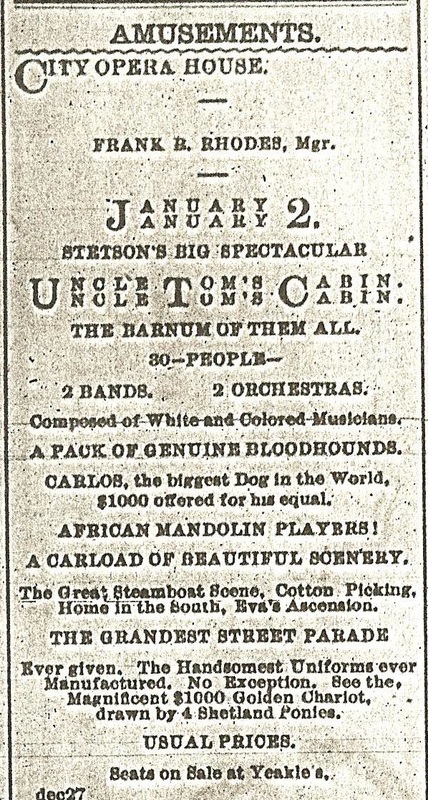

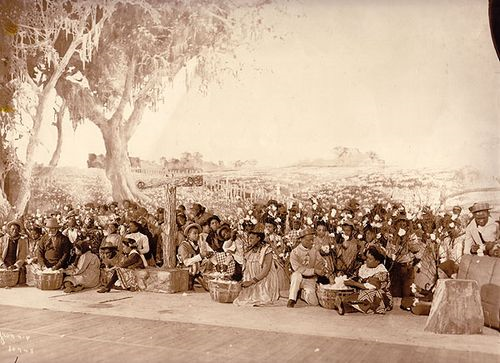

In last week’s blog, we talked about the forgotten Frederick “hot spot” known as Love Lane. Today, it’s commonly known as East Street. In part 2 of this “Valentine themed” Frederick history post, I want to revisit another romantic local option for couples living a century ago. This was the newly laid out Lover’s Lane, part of a larger amusement resort known as Lake View, the “lovechild” of county businessman Charles J. Ramsburg. Located six miles north of the City of Frederick, rail transportation could bring pleasure seekers to a peaceful setting that featured a casino, hotel and namesake lake. Ramsburg was a native of nearby Lewistown, having grown up on a farm originally laid out by his grandfather Jacob. In addition to the family trade of farming, Charles found success in the late 1800’s goldfish boom, and was one of the county’s largest exporters. Ramsburg was also an investor in the Westminster, Frederick and Gettysburg Railroad, which would traverse property owned by his family. He would obtain this land and concoct a scheme to cash-in on the new trolley line that would connect Frederick and Thurmont. In 1908, Charles Ramsburg merged his many fishponds together, forming a large lake in the shadow of picturesque Catoctin Mountain to the west. Now that he had an attractive setting, he looked to capitalize on the rail transportation line’s ability to deliver visitors in same manner as neighboring local mountain retreats such as Braddock Heights and Pen Mar Park. At the top of a hillside that overlooked his manmade lake, Mr. Ramsburg began construction on an elaborate amusement structure in the form of a casino. Once complete, this would be a two-story building, 116 by 90 feet, with a first class skating rink and beautiful dance hall. On the first floor were located four bowling alleys, a pool room, and cloak and toilet rooms. Guests were invited to utilize the lake for bathing, swimming and boating as row boats were made readily available. For others, a romantic stroll on Lover’s Lane took guests around the perimeter of the lake—certainly worth the trip to the new resort. One month prior to opening his casino, Mr. Ramsburg nearly experienced a disaster when his structure was struck by lightning as finishing touches were being added. A newspaper account from August 9, 1908 says that minimal damage was suffered and project workmen were “slightly stunned by the bolt.” The Lake View Casino opened in early September, 1908, and the venture seemed an instant success, prompting Mr. Ramsburg to make plans to construct a neighboring hotel. This would become a reality. Four stories in height, the hotel afforded magnificent views in all directions, made all the more accessible with a roof garden. The structure was described as “magnificent,” readily equipped with all modern conveniences and having the ability to accommodate up to hundred guests at a time.  Sadly, the full potential of the site was never seen. The casino experienced a devastating fire just prior to the grand opening of the hotel in May 1910. Two explanations for the fire survive: one that a candle fell into Spanish moss causing the fire; and another points to arson. Ramsburg had grossly under-insured his building, and with the outlay for the hotel, he was not in the position to rebuild the casino. The Lake View Hotel hosted pleasure-seekers over the next four years but would suffer the same fate as the casino on June 16, 1914. Just days before opening for the summer season, the Lake View Hotel burned to the ground. This time, a faulty heating apparatus was to blame. Mr. Ramsburg should have taken that earlier lightning bolt as a bad omen. Charles Ramsburg gave up on his endeavors in the hospitality resort industry, and went back to an enterprise that was decidedly “fireproof.” In the 1920 census, his occupation is listed as that of a pisciculturist—aka fish breeder. He had returned to putting his full attention to the business of raising goldfish.

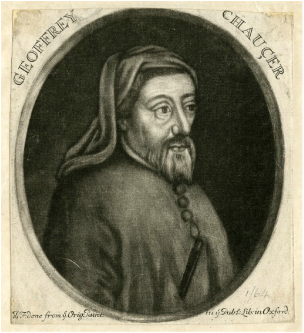

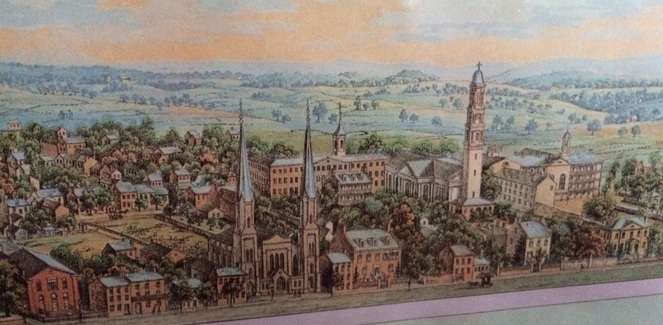

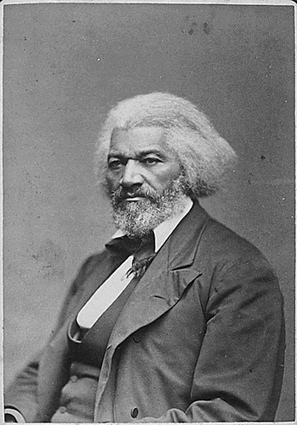

In 1916, the Maryland Conservation Commission had assessed the state for future fish hatcheries, especially with regard to trout. The following year, Lewistown was selected for the commission's first hatchery. In the process, the state would also stock Ramsburg’s Lake View lake with a supply of small-mouth bass, crappie and catfish. Lake View once again became the scene for “lovers,” but this time, it was solely of the aquatic variety. Mr. Ramsburg’s influence would also have a profound effect on the son of his next door neighbors Milton and Rosanna Powell. Their son, Albert M. Powell would develop a love of fish as well, destined to serve as the longtime Superintendent of Maryland State Fish Hatcheries.  Artistic depiction of ancient Lupercalia festival. Artistic depiction of ancient Lupercalia festival. Well, we have officially navigated past Super Bowl Sunday, and it’s time once again for another fabricated, commercial-based, “pseudo holiday.” Welcome to Valentine’s Day! As opposed to the Super Bowl, Valentine’s Day certainly requires a bit more creative thought and, at times, stealth planning by participants in advance. Luckily, living here in a place like Frederick County, Maryland offers the opportunity to easily garner tangible members of the 4 major Valentine food groups: 1.) jewelry 2.) chocolate/candy 3.) flowers 4.) clothing/lingerie (of any rating) Interestingly, gifts are merely an invention of the last century, adding a new degree of stress and pressure. Now 2,000 years ago, the yearly occurrence that grew into today’s Valentine’s Day required a simpler effort by everyone involved. In ancient Rome, during the month of February, a fertility-themed feast called Lupercalia was held in honor of the wolf-god Faunus, a Roman knockoff of the rustic Greek god Pan. The names of young females were secretly placed in a box and shaken up. The young men drew a name and, voila, each obtained what we would equate to be his valentine. Five-hundred years later, the leaders of the early Christian church “muscled in,” wanting to rid the empire of pagan ritual and superstition. Males now had to draw the name of a saint, instead of that of a young maiden, and were expected to imitate the example of said saint’s life with emphasis on sacrifice and humility. The ladies then pursued the “holy portrayer” that attracted them most.  Geoffrey Chaucer (1343-1400), "the Father of English Literature." Geoffrey Chaucer (1343-1400), "the Father of English Literature." So where does St. Valentine come into play? And how is he associated with love? Well, it’s a long story, but the namesake got his initial start as being one of the many saints imitated. Actually, there were several martyred Valentine’s over the years, so his name came up often! This lasted throughout the balance of the Middle Ages, and St. Valentine was still not the love-wielding “go to guy” we know him as today. This would come centuries later as many scholars give the credit to Geoffrey Chaucer (1343-1400), he of Canterbury Tales fame. The first recorded association of St. Valentine, Valentine's Day and romantic love can be found within Chaucer’s poem Parlement of Foules (1382) in which he wrote: “For this was on seynt Volantynys day Whan euery bryd comyth there to chese his make.” I’m guessing you may have just experienced a cruel flashback to high school sophomore year English class. So I will gladly assist with the translation: "For this was on St. Valentine's Day, when every bird cometh there to choose his mate." This is some sweet prose, and surprisingly from the same guy who gave us our first educational foray into flatulence humor with the Miller’s Tale. Not only did Chaucer’s line above build a context between Valentine’s Day and romance, it also gave rise to the expression of “love-birds” and thus, the euphemism involving “the birds and the bees.” St. Valentine quickly became the “poster-saint’” for amour and affection, and this would directly create a greeting card industry—of course with much deserved props also going to Johannes Gutenberg as well. I journeyed back in Frederick’s past to see what the local newspapers were saying about Valentine’s Day. In the latter 19th century, I found that it was a time in which the Valentine card itself was the central focus. Some were ornate, made of fancy ribbon and lace. Others were die cut. Many ornate cards were imported from Europe. Several businesses of town carried Valentine’s cards and I assumed that this was a profitable occasion for newspaper owners as well since they had printing means to be purveyors of cards themselves, and collected increased advertising from merchants and event organizers marketing Valentine-oriented wares and activities. I was quickly taken aback, however, by the tone used by the writer of an article in the February 7, 1887 edition of the Frederick (MD) Daily News:  1854 Sachse & Co. lithograph View of Frederick looking north from East Church St. and showing the northeastern boundary of the city. 1854 Sachse & Co. lithograph View of Frederick looking north from East Church St. and showing the northeastern boundary of the city. Today, Frederick offers so many opportunities to truly experience and enjoy the Valentine occasion with significant others. A plethora of restaurants can host the traditional Valentine’s dinner. Varied entertainment venues and amusements can be enjoyed. In addition, we also have plenty of historic churches to choose from for those desiring an “old-school” experience (to study up on saints and saintly behavior.) And with the current exception of a downtown hotel and conference center, there are plenty of lodging choices (some romantic, and others simply functional) for out of town visitors. In flipping through antiquated newspapers of the early 20th century, I stumbled upon a few opportunities afforded our ancestors “back in the day,” but not available to young (and old) sweethearts in Frederick at present. One of these included the forgotten address of Frederick City's most romantic spot— Love Lane. Love Lane was a moniker given to Frederick’s East Street, and seemed to be in fashion during much of the 1800’s. I have seen it used going back to 1822, five years after the city was first incorporated. At the time, this dusty path was the eastern boundary of town, and ran between today’s South and 7th streets. The opposite of bustling Market Street, Love Lane featured beautiful vistas of rolling hills and farmland to the east, and small homes, quaint street corners, and the eventual St. John’s Cemetery, all with a splendid backdrop provided by Catoctin Mountain to the west. Beautiful sunsets and feelings of serenity must have been welcome escapes for city dwellers of all ages. A reconvening with nature here was the second best whimsical destination that Frederick could offer—the first being Mount Olivet Cemetery (opened in 1854) and located a good hike south of town. However, the latter garden-cemetery was not the ideal romantic location for a young couple’s dreamy first date or a budding relationship. All good things must come to an end, and that was the case with Love Lane. The post-Civil War period brought the Pennsylvania Railroad right down Love Lane, eventually setting the stage for industry to locate sidings adjacent its right of way. Lumberyards, foundries, the gas works and brick plants sprouted up. At least a tannery on Carroll Creek in this vicinity was owned by the fittingly named Valentine Byerly. Some couples simply ignored the progress and remained “young at heart, regardless of intrusions.” One such was Clara V. Mott who wrote a poem about Love Lane in 1909. A regular contributor to the Frederick Daily News, Mrs. Mott was known for her Moments With the Muse column. She was also a resident of East 7th Street, and on one occasion took to reminiscing about a happier time. She wrote this piece a year after the passing of her husband Albert, a former Union Civil War veteran. A century of growth has drastically changed the once paradisiacal route. Starstruck couples walked elsewhere. The memory of Love Lane would further fade with the opening of Baker Park in the late 1920’s, and a number of charming neighborhoods that soon surrounded it. Meanwhile, the early industries gave rise to 20th century giants like Frederick Iron and Steel, the Economy Silo Factory, Ox Fibre Brush and the Everedy Company. And who can forget the “loveable” Reliable Junk Company? A jaunt with one’s steady gal adjacent Shab Row and Everedy Square is far better today than it was fifty years ago. But I think it’s still a stretch to find romance while walking “hand in hand” a few blocks further north through the current assemblage of auto repair establishments, a power transformer sub-station, junk yards, 7-11, plumbing repair warehouses, etc. There is a reason why it’s back to being called East Street, and not Love Lane anymore! At least on the north-end extension (of this storied thoroughfare), recent generations of lovers could find “heartwarming delights” at the old Freeze King, while new generations can fill the latter’s void with the Family Meal Restaurant . Most importantly, love on the old lane can still be found in the form of Love and Company, a local firm that specializes in senior living marketing, for what it’s worth. Another Lovers Lane once existed in Frederick County, and I will tell you all about it in next week's edition of the HSP "Hump Day History" Blog entitled: Frederick and Valentine’s Day—Part 2: A hunk of “Burning” Love. Last week, my family and I took the opportunity to eat lunch with friends in Downtown Frederick on a weekday. It was the grand finale of the string of school “snow days” made possible by the incomparable superstorm Jonas. We chose to dine at Brewer’s Alley, a restaurant living within a structure steeped in Frederick history and heritage. From the menu, one can note that the ownership takes pride in promoting the establishment’s standing as Frederick County’s First Brewpub (established in 1996). This tid-bit will likely be noted by future historians a century from now, I’m sure. The popular “eatery/watering hole” is currently undergoing a major renovation project which will expand the kitchen, and downstair's main dining rooms. Interestingly, this building, and the property it sits on, is no stranger to “makeovers.” It has experienced plenty of them over the past 250 years. And those who know me, certainly can acknowledge that I’m no stranger to the story of this place—one that dates back to the Colonial Period.  The original Market House of Frederick (1769-1873). Courtesy of the Historical Society of Frederick County. The original Market House of Frederick (1769-1873). Courtesy of the Historical Society of Frederick County. The early residents of “Frederick-Town” held a lottery to raise money to build a town hall and market house on this location. Completed in 1769, this structure served its purpose for well over 100 years and would stand witness to a rapidly growing city around its foundation. A century later, the Market House was the site where town leaders scrambled to come up with a plan (and money) to keep Confederate Gen. Jubal Early and his Rebel Army from doing harm to their city after levying a hefty ransom of $200,000 (July, 1864). Less than a decade later, the old Market House was demolished to make room for the current building, a much more spacious home for municipal quarters on the upper floors and upgraded “butcher stalls” remaining on the ground floor. Construction began on the new Frederick City Hall in 1873, with plans for a unique element to be added towards the rear—a large multi-purpose room that could accommodate meeting, exhibition space and best of all, entertainment programs.  Frederick Douglass (1879). Frederick Douglass (1879). Now back to our family lunch experience last week. Almost on cue, one of my sons took pride in telling the rest of our table what happened that night. He recanted that the legendary Frederick Douglass actually ate here. Well, he was half right. I don’t know about the dining accusation, but the renowned orator and former editor of The North Star anti-slavery newspaper presented his “Self-made Men” lecture in this building on the evening of Sunday, April 8, 1879. The Frederick Examiner newspaper heralded Mr. Douglass’ appearance and performance, describing the guest speaker as having: “...a very attractive, musical voice of great compass, a fine and commanding and prepossessing appearance, easy and graceful delivery, and a faculty of commanding the profoundest attention from his hearers.”  Brewer's Alley restaurant, located at 124 N. Market St. in Frederick, Maryland Brewer's Alley restaurant, located at 124 N. Market St. in Frederick, Maryland Since the day I first found this dusty news article, years ago, I have always been impressed with the reporter’s strong character assessment toward the end of the piece: “It was a single phenomenon that one, born and raised a slave in our own State, could by his indomitable will and earnest labor have so educated himself as to be received as a public instructor by all classes.” I find it fascinating to think about the life experience of Frederick Douglass (1818-1895), one that began on Maryland’s Eastern Shore in bondage, and ended with overwhelming reverence and international super-stardom. Just 20 years prior to Douglass taking the stage in Frederick on that April night, another legendary freedom fighter, well-known to the speaker, went to nearby Harpers Ferry and began the war that ended slavery (1859). This was John Brown, and Douglass was well aware of his ill-fated plot since the get-go. Frederick County boasted Unionists and Southern Sympathizers along with a population of both free and enslaved Blacks, a rare combination found in few places in the country. Soldiers of both armies marched by the former Market House site, eventually taking each other’s lives on nearby battlefields. Mr. Douglass was truly a remarkable figure in forging the history of our nation. But there’s at least one thing he didn’t do—and that‘s eat at Brewer’s Alley —a location that could be argued the virtual “North Star” of Frederick by residents and tourists alike. (Note: For more on Douglass’ “Self-made Men” speech, follow the links below.)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Self-Made_Men https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BfgzUE3Okww |

AuthorChris Haugh Archives

February 2024

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed