HSP HISTORY Blog |

Interesting Frederick, Maryland tidbits and musings .

|

|

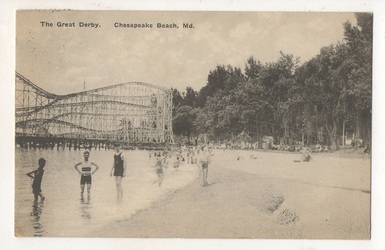

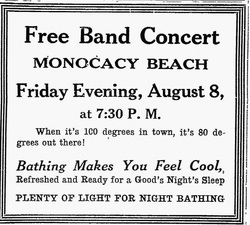

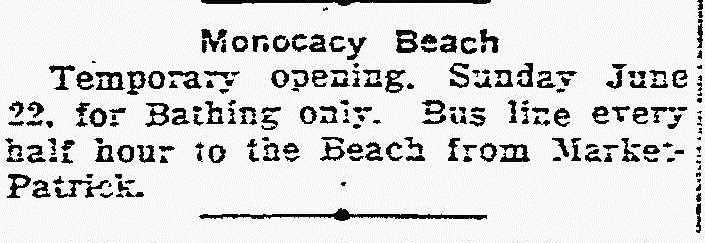

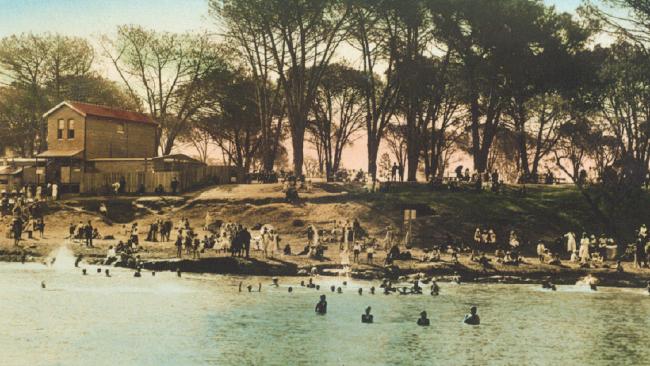

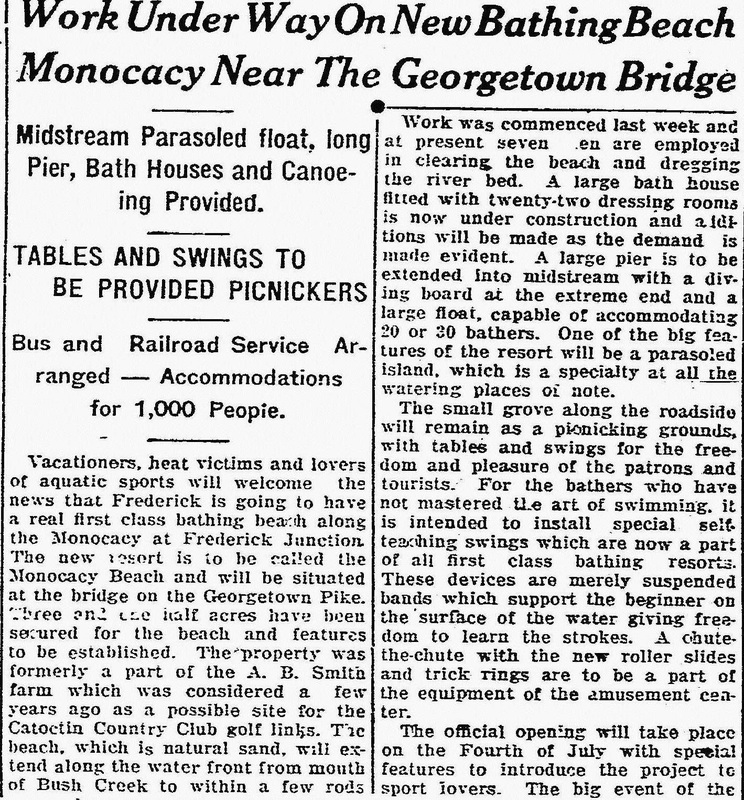

With Arctic-like temperatures last week, followed by nearly three feet of snow received over the weekend, it’s safe to assume that most of us are desperately wishing for summer, and warmer surroundings. I, myself, have fixed thoughts on the beach, and I’m sure I’m not alone here. I know it’s not the right season, but at one time, long ago, Frederick residents didn’t have to travel far to reach the shore. A place called Monocacy Beach was their proverbial “oyster.” Each of us “beachcombers” may have a different sandy setting in mind. For most people, Ocean City probably is their first choice. To me, it’s the Delaware beaches (Fenwick, Dewey, Rehoboth and you can throw Bethany and Lewes in there as well). Others may think of the Jersey Shore, Virginia Beach or the Outer Banks of North Carolina or Myrtle Beach. And of course, there are the legendary beaches that can be experienced as we speak, both coasts of Florida and tropical paradises found throughout the Caribbean. When looking back 100 years ago, the options were a bit different as travel made treks much more difficult, especially to the shores of Delmarva. Atlantic City reigned supreme, and Virginia Beach was another storied destination. But for most folks, going to the beach actually meant going to the Chesapeake Bay, not the Atlantic Ocean. The ocean vacation would not gain great popularity in our area until the post-World War II “beach boom” and completion of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge (in the early 1950’s). After an earlier war, the “Civil” one, people began to look for recreation amidst the fresh breezes and salt waters of the Chesapeake Bay. Resorts began to spring up in the decades to follow, catering to people of the state’s Western Shore—particularly Baltimore and Washington, DC. These would become economic and promotional tools of railroads and steam boat lines, the two best transportation means of the day. Day trip and long term excursionists could not resist the temptation.  Chesapeake Beach in the "Roaring Twenties." Chesapeake Beach in the "Roaring Twenties." I first became interested in these bayside recreation/amusement resorts when my brother moved to Chesapeake Beach (Calvert County) in the 1990’s. Chesapeake Beach was the byproduct of a short railway built from the nation’s capital, and boasted a hotel with slot machines and a fine amusement park. I also read about other offerings such as North Point, Gibson Island and Highland Beach (for the segregated Black population), and others across the Bay and serviced by steamers: Rock Hall, Betterton Beach and Tolchester Beach near Chestertown. Chesapeake Beach’s population reached the 10,000’s during the heyday of the 1920’s before a devastating fire torched the hotel, coupled with the nation’s economic downturn courtesy of the 1929 stock market crash and Great Depression to follow. Back in 1999, I found myself on a boat in the lower Potomac River, just south of Mt. Vernon. I was performing film work of capturing scenes of nearby Piscataway Park (NPS) for a documentary on the early Piscataway Indian tribe that once inhabited the area. This is the land of today’s Southern Maryland (primarily Charles County). My friend Bill, captain of the boat, pointed out to me the desolate remains of Marshall Hall, a one-time riverside beach/amusement resort that once catered to nearby Washington DC’s population. It would have origins dating back to 1868. A small amusement park lasted decades and was supplanted with a larger, more modern park in the late 1960’s The operation lasted until 1980, at which time the land came under the ownership of the National Park Service and was dismantled. One day, while skipping through microfilm of Frederick newspapers, I landed on an interesting item in the Frederick News from June, 1924. It was a story announcing a new recreational bathing opportunity for residents—Monocacy Beach. This attraction was located near Monocacy Junction, and officially opened almost exactly 60 years after the critical “Battle that Saved Washington” took place. Billed as “a first class bathing beach,” it was constructed near the vehicular bridge across the namesake waterway, along the Georgetown Pike (MD355).  Monocacy Beach could accommodate nearly 1,000 persons at a time. Once complete, Monocacy Beach would boast a bathing house, picnic grove, parasoled island, diving pier and special self-teaching (swimming) swings. Open from 1pm until 10:30pm, bus and train transportation from Frederick would bring patrons to the resort for both day and night swimming, the latter courtesy of installed electrical lights. The idea was the brainchild of a 37 year-old New York native, Edward Dietz. He was said to be a relative newcomer to town who conducted a Community Window Cleaning and Decorating Company, a service utilized by many of Frederick City’s downtown merchants. Dietz appears to be living in Hagerstown in the 1920 census and in 1922-23 had been conducting a like business there. After it’s July 4th, 1924 Grand Opening, I read mentions of many local civic and fraternal groups heading to the new beach for outings, while advertisements announced special entertainment such as concerts. Unfortunately, I have not been able to find out much more about the Monocacy Beach resort operation after that opening summer of 1924. I found Mr. Dietz living in Hagerstown as late as 1929, listed in a city directory as a window cleaner. He appears in the 1930 census the next year in Winchester, VA. It can only be assumed that his time in the "beach resort" business was shortlived—likely lasting just that first summer. Perhaps interest in the business waned, investors pulled out, or the following winter season came with a destructive force courtesy of Mother Nature in the form of a devastating flood or worse yet, a crippling three-foot blizzard. That would be ironic, wouldn’t it? Life's a beach!

3 Comments

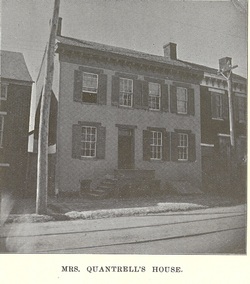

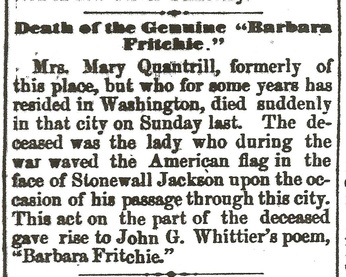

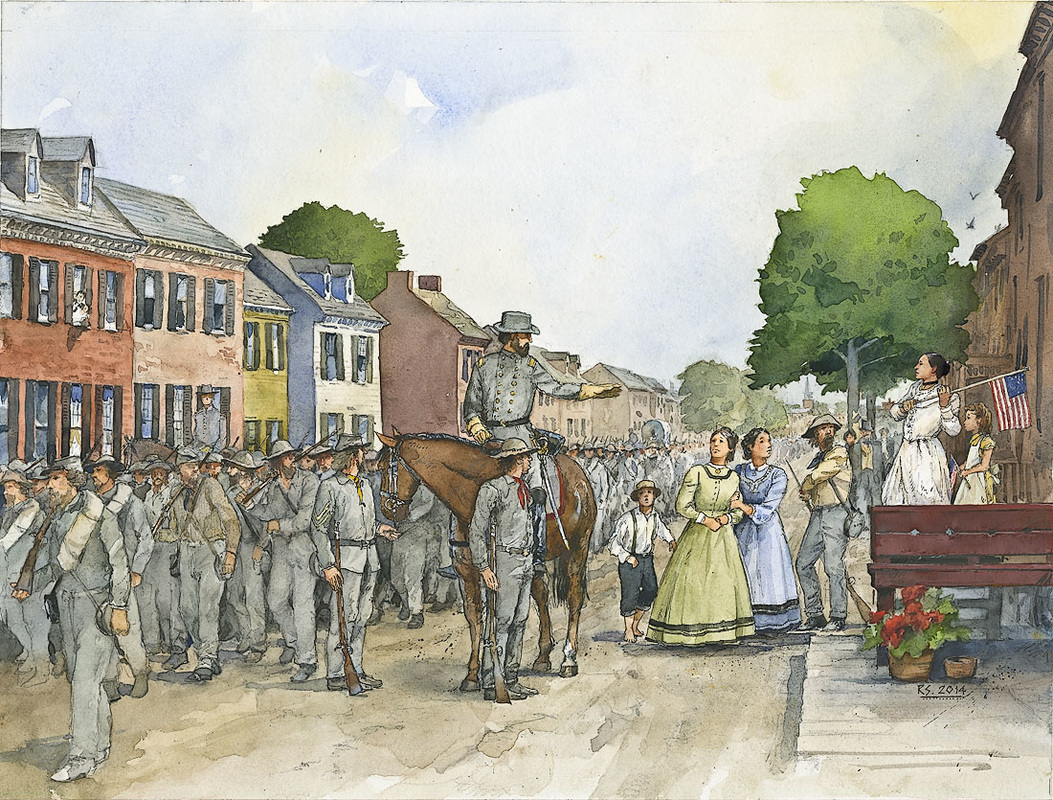

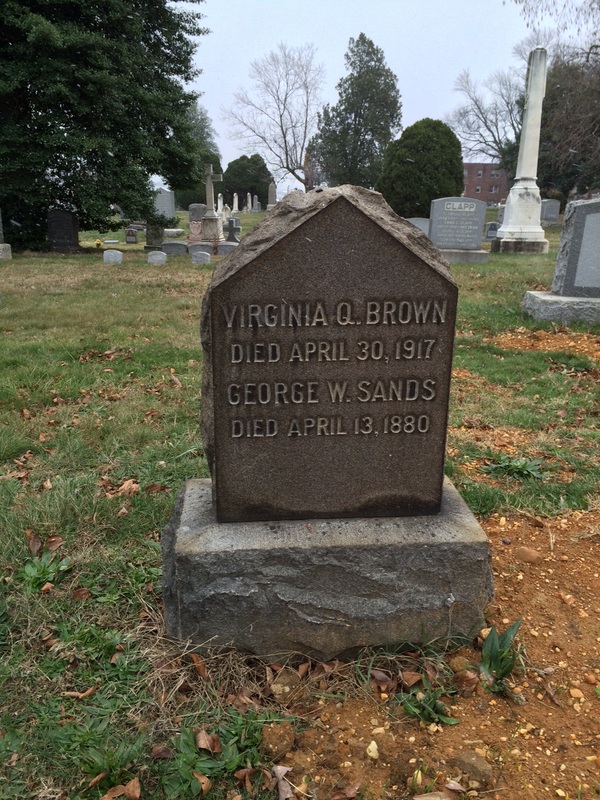

The other morning I had to drop my stepson Jack at Reagan National Airport. He was heading to sunny Orlando, along with classmates in the Thomas Johnson High School marching band, to perform at Disney World and have a great week of meeting and learning from other bands and students. I couldn’t just make the trip down to DC and come back home without a side trip, especially due to the fact that it was a Sunday morning—a rare and unfettered opportunity to take in one of the many attractions that our nation’s capital affords. I decided to take a detour from the George Washington Parkway and drive into the District via Memorial Bridge. I drove around the National Mall and contemplated an ultra-quick museum visit to one of the Smithsonians, or perhaps perform some quick research at the National Archives, but decided I didn’t have that much time available since I had people coming to my house that afternoon for a “get together.” I eventually opted to visit an “old friend,” one whom I have diligently studied, and gotten close to, for nearly 10 years—Mary S. Quantrill. I know the name may not necessarily “roll off the tongue” or ring a bell, but for lifelong Frederick residents and Civil War wonks it should. Instead, this woman was denied her place in the pantheon of American history. Born Mary Sands in Hagerstown in 1823, my subject grew up on Frederick's West Patrick Street, married and would eventually serve as a schoolteacher of girls in the location of her childhood home (220 W. Patrick). Mary’s husband, Archibald Quantrill, was the son of a War of 1812 officer, and spent most of his life in Washington, DC, where he worked as a newspaper typesetter. At the outbreak of the Civil War, Archibald thought it best that Mary and young children reside in Frederick with Mary’s elderly mother, as Washington could be a prime target for Confederate attacks. Mr. Quantrill was proven wrong in early September, 1862, when Frederick was the first, major "Northern" town Gen. Robert E. Lee would bring his C.S.A. army after crossing the Potomac River. Many know the story that the Confederates were basically given a cold reception, save for a smattering of Southern-leaning residents. Not getting the assistance he had hoped for, Gen. Lee headed west toward South Mountain, utilizing the National Pike to transport his vast army. West Patrick Street was part of this great road, and Mary Quantrill would have a front row seat for the "Rebel Parade" out of town which began in the early morning hours of September 10. She even had her Union flag in hand to send off the Rebel horde. Mary Quantrill made a lot of noise that day, and was certainly noticed by soldiers, officers and a number of Patrick Street residents. However she didn’t make a name for herself—or should I say, she didn’t get help from a Georgetown novelist (E.D.E.N Southworth) or Quaker poet from Massachusetts (John Greenleaf Whittier). In late summer of 1863, these literary luminaries had an Abolitionist agenda to tend to, and fast-tracked a work of prose that featured Mary’s feisty neighbor—a nonagenarian who lived a football field’s length down the street. The name of Barbara Fritchie (or Frietchie) rang true as not only Frederick’s heroine, but that of a nation, or at least the part of it that was intact as the Union at that time.  Barbara Fritchie, "the famous, other woman." Barbara Fritchie, "the famous, other woman." Dame Fritchie didn't live long enough to enjoy her fame, as she died at age 96, 11 months before the poem was published in October, 1863. On the other hand, Mary Quantrill lived for another 17 years, and found it difficult to escape the praise and adoration her former neighbor received for "starring" in the poem, and doing what she, herself, had done in displaying true courage and devotion to her Union cause in a daring act of West Patrick Street flag-waving. Amazingly, no one saw Barbara harass the Confederates on that fateful day. I could go on with this subject, as Mary certainly holds a place in my heart of hearts as the brave and brash woman who would never see her day in the limelight, not to mention the history books. Instead she was scorned for attempting to "hone-in" on Barbara’s fame. She died in 1879, and I have surmised it was a broken heart. The actual cause on the death certificate is cardiac disease, endocarditis...so close enough. You can learn more with these two links that feature my former writings on the subject, The Journal of the Historical Society of Frederick County (Fall 2008) and Maryland’s Heart of the Civil War: A Collection of Commentaries: http://www.historysharkproductions.com/past-projects.html http://browndigital.bpc.com/publication/?i=251369&p=106  Frederick Daily News, August 7, 1879 Frederick Daily News, August 7, 1879 Mary’s final resting is Glenwood Cemetery in NE Washington, DC, off Lincoln Ave. You will have trouble finding her, as she is buried in an unmarked grave. As a matter of fact, all the Quantrill’s are unmarked, except a daughter Virginia Quantrill Brown, who participated in the underplayed flag waving incident of 1862 on Mary’s front porch. I deduct that the name of Quantrill was Mud (or Mudd) for a couple of reasons. A cousin through marriage was the first to mess things up—this was William Clarke Quantrill, he of Quantrill’s Raiders fame. The second strike against Mary was an 1869 letter to the editor in which Mary gave a detailed first person account of her flag waving experience. This is when the major backlash started as many perceived Mary to be a “Pretender” trying to steal the limelight from Barbara Fritchie, one our “greatest American heroes.” Last Sunday morning, as I drove through the front iron gates of Glenwood, snow flurries began falling. From memory, I knew exactly where the lonely Quantrill grave plot was located. I parked, and walked over to the hallowed ground. I immediately felt pity for Mary all over again. As I stood there, I felt inclined, however, to tell Mary a bit of good news since last I had visited her. Thanks to some grant money, and a generous contribution from a local financial planner (Scott McCaskill) with help from the Frederick Woman's Civic Club, there is now an interpretive wayside marker in front of her old house (220 W. Patrick St. As I turned to walk away, I could have sworn I heard a faint woman’s voice say, “That’s great "history boy," now work on getting me a tombstone."

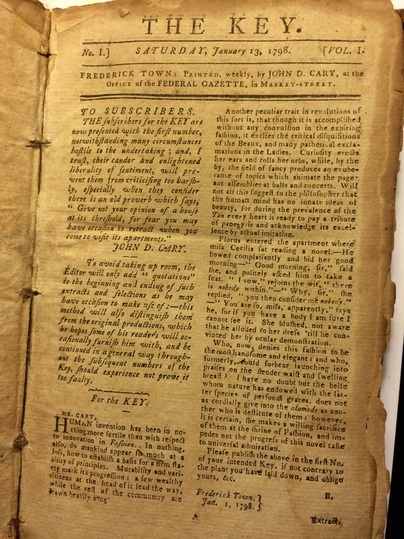

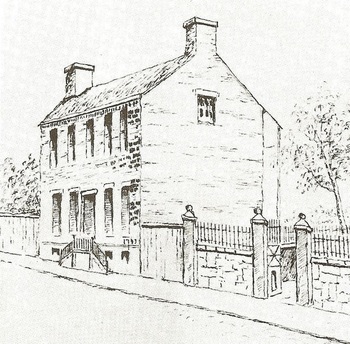

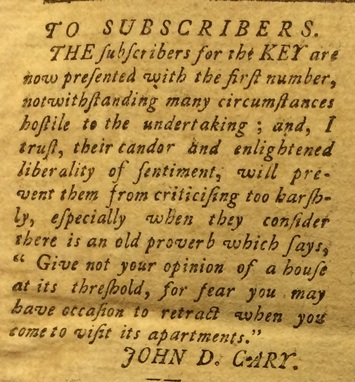

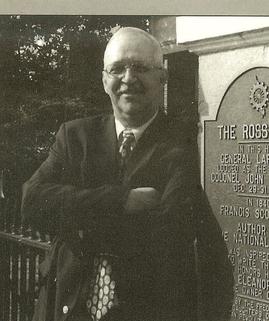

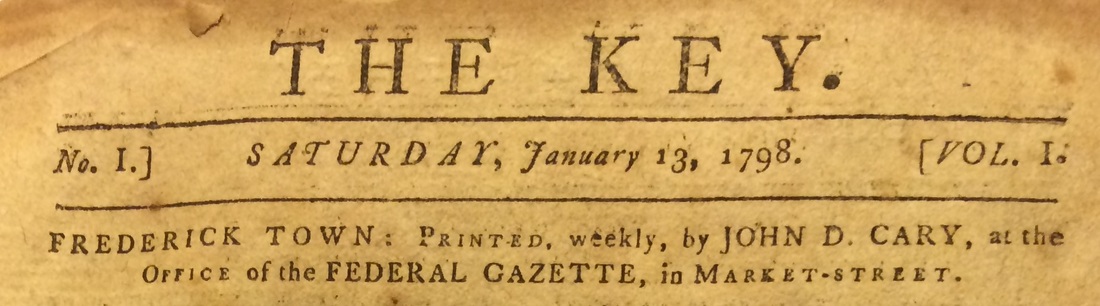

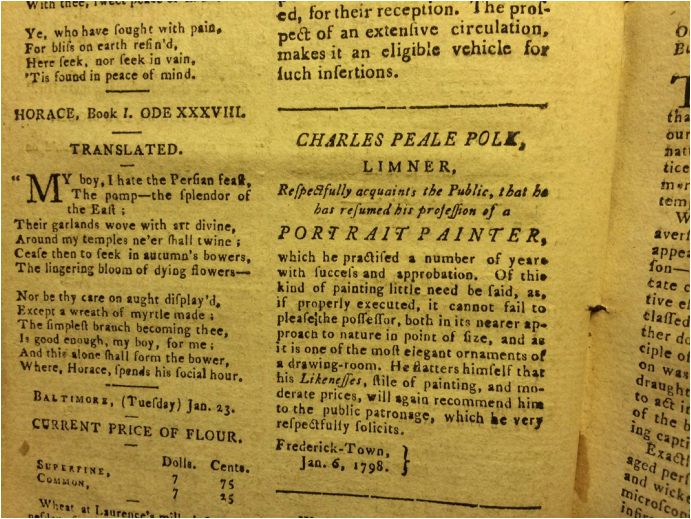

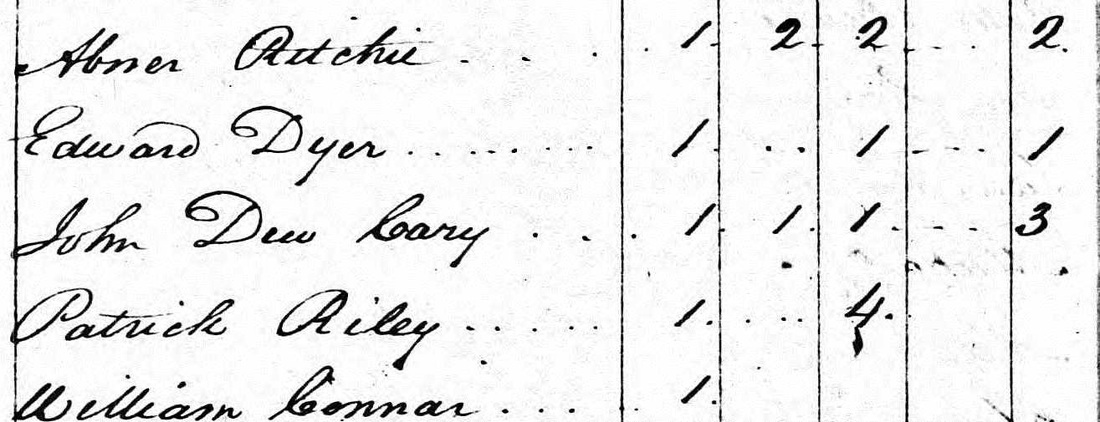

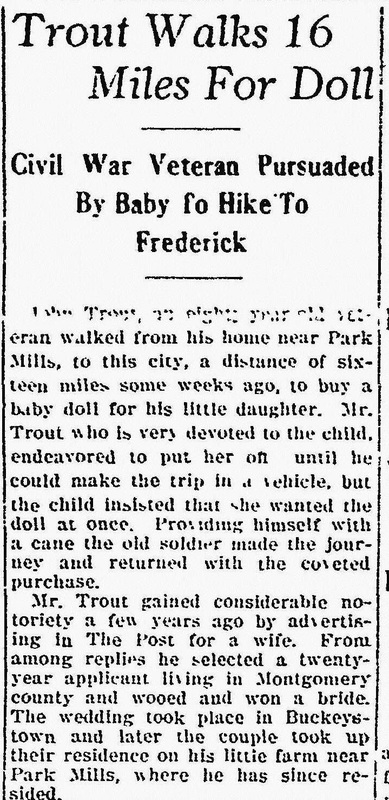

I consulted a former published work by my friend, and history mentor, John Ashbury for topic inspiration this week--"And all our yesterdays, a chronicle of Frederick County, Maryland.” John’s book, published in 1997, is centered on the premise of tying history to actual dates, a beautiful art form unto itself for us “history geeks.” The author painstakingly spent years combing through thousands of microfilmed, local newspapers in his research effort to produce a daily chronicle—one that calls out important and noteworthy Frederick County-related events and personalities. Best of all, these are tied to all 365 days of the year as the book can be used in the same vein as that novelty mini tear-off calendar you probably received over the holidays….and equally entertaining I promise!  I find myself utilizing John’s book religiously “time and time again,” (please pardon the unintentional pun) and it occupies a place of honor in my vast collection of historical and archival research resources. So when I looked up today’s date of January 13, I found a reference to one of Frederick’s earliest newspaper publications with a very familiar “Frederick” moniker attached to it. John’s book tells us: “January 13, 1798—The first issue of “The Key,” was published by Dr. John D. Cary, who named the newspaper in honor of John Ross Key. It lasted but three years.”  Cover page of the inaugural issue of The Key (January 13, 1798). Cover page of the inaugural issue of The Key (January 13, 1798). Not that other tidbits on this date of “January 13” were lesser in importance (ie: the death of Hood College foundress Margaret S. Hood (1913), the incorporation of Emmitsburg by an Act of the General Assembly (1825), and the retirement of beloved WFMD radio personality Happy Johnny Zufall (1971)), but this passage resonated with me immediately. The Key, as I have understood, was styled as somewhat of a “poor man’s” Poor Richard’s Almanac, sharing wit and wisdom, political views, and the price of flour, along with serving as a vehicle for local advertisers of course! I have not been successful in finding the relationship between publisher John Cary and the supposed namesake Key family. However, John Ross Key was a leading individual in the community, local Revolutionary War officer and Frederick County court justice. His son Francis Scott Key was attending to studies at St. John’s College in Annapolis at this time, long before his patriotic “flag-spotting” days. Ironically, one month ago, in mid-December, I found myself engrossed in a Frederick history conversation about John Cary and his fabled newspaper. I had been invited to lunch by an old friend, who not only has family roots reaching back to Frederick’s founders, she also owns a rare, bound volume of The Key amongst her rich collection of Frederick artifacts and memorabilia. It was on this day that I found myself given the opportunity to hold Cary’s 218 year-old newspaper in my own hands and reading the actual antiquated pages with my own eyes. It was quite a thrill as I had just talked about Cary and his publication last fall during a lecture for my Frederick County Explorations class (Frederick Community College’s Institute for Learning in Retirement program). Unfortunately, there still seems to be a shroud of mystery surrounding the age-old factoid that appears about Cary and The Key in John Ashbury’s book, along with the same scant mention in numerous other Frederick histories and newspaper articles over the last 150 years. So I went “in search of” John Cary with some home-based book and internet research. I was already armed with knowledge that there was a connection between the Cary family and Frederick’s St. John the Evangelist Catholic Church, something I will cover momentarily.  Beatty-Cramer House, built ca. 1732. Owned and maintained by the Frederick County Landmarks Foundation Beatty-Cramer House, built ca. 1732. Owned and maintained by the Frederick County Landmarks Foundation In looking at John Cary’s ancestry, I was fascinated to find that he was the great-grandson of Frederick County’s most celebrated female pioneer and early landowner, Susanna Asfordby Beatty. Susanna Beatty came down from Kingston, Ulster County, New York around 1732, an aged widow accompanied by 8 of her 10 adult children and their families. She acquired a few thousand acres of land from Frederick’s founder Daniel Dulany, and owned much of the vicinity south of today’s Walkersville, stretching from the Monocacy River to Mt. Pleasant. You may recognize the family name as it adorns Frederick’s oldest “still-standing” dwelling, the Beatty-Cramer house on MD26 just east of Ceresville at Israel’s Creek. One of Susanna’s sons was Thomas Beatty, Chief Justice of the 1765 Frederick County Court that gave us the legendary Stamp Act Repudiation of 1765 (recently commemorated locally in honor of its 250th anniversary). Susanna also gave us William Beatty, John Cary’s maternal grandfather. William would acquire the “home plantation” (today’s Glade Valley Farms) upon his mother’s death in 1745. William’s daughter Mary would be raised here, and would eventually wed an Irish merchant (possibly a printer and/or physician) by the name of John Cary (1717-1777). Our subject, John Dow Cary, would come from this union, and was likely the oldest child among a number of siblings, many of which would eventually head to Ohio around 1830.  The first Catholic Church in Frederick County, located on East Patrick Street. Father John Williams had constructed a chapel on the second floor. The first Catholic Church in Frederick County, located on East Patrick Street. Father John Williams had constructed a chapel on the second floor. The elder John Cary had a major role in providing property for the first Catholic Church in Frederick County. He owned several small parcels in Frederick dating back to the 1750’s, but donated lots 97, 98, and 99 in October, 1765 for the measly sum of five shillings, having paid fifty times that amount just a few years prior. The lots were on the north side of East 2nd Street, directly across the street from present St. John the Evangelist Church (not constructed until 1833). A small brick building on the former Cary property, two stories in height, would begin serving the Catholic community under the leadership of Father John Williams. This humble building would continue to do so until Rev. John Dubois would began building his Church of Saint John in the year 1800. This impressive structure would be located on the same cluster of former Cary properties on the north side of East Second Street, specifically on the corner lot that aligns today’s aptly named Chapel Alley. In 1834, DuBois’s church would be entombed within the Jesuit Novitiate that stretched nearly the entire block. The younger John Cary is said to have been born in Frederick County and was a physician as well. Like his father, we know with confidence that this John Cary of Frederick Town would serve as a printer/publisher. He began helping John Winter with his newspaper weekly Rights of Man which had a run from 1794-1800, and was printed in a shop on West Patrick street across from Mrs. Kimboll’s Tavern. He would begin publishing The Key in 1798 and would continue through 1800. It has also been recorded that Cary had a business relationship with Mathias Bartgis, the German immigrant who gave Frederick the Maryland Chronicle, it’s first English language newspaper, originally established in January, 1786.  Special editor's note from the very first issue of The Key (January 13, 1798) Special editor's note from the very first issue of The Key (January 13, 1798) The younger John Cary is said to have been born in Frederick County and was a physician as well. Like his father, we know with confidence that this John Cary of Frederick Town would serve as a printer/publisher. He began helping John Winter with his newspaper weekly Rights of Man which had a run from 1794-1800, and was printed in a shop on West Patrick street across from Mrs. Kimboll’s Tavern. He would begin publishing The Key in 1798 and would continue through 1800. It has also been recorded that Cary had a business relationship with Mathias Bartgis, the German immigrant who gave Frederick the Maryland Chronicle, it’s first English language newspaper, originally established in January, 1786. I found a reference to John D. Cary in Edward Papenfuse’s “A Biographical Dictionary of the Maryland Legislature 1635-1789” (Volume 426, Page 202-203). Not a resounding character sketch, but it states that Cary was married and possibly had a son, but names remain unknown. Cary is noted for his participation in the Revolutionary War, serving as a sergeant with the Maryland Militia in 1777, an ensign with the Second Maryland Regiment in 1781 and achieved the rank of 2nd lieutenant in 1781. He resigned his commission in April 1783 and promptly represented Frederick County in the Lower House of Maryland’s General Assembly in 1784 and 1785. His recorded occupations include physician and planter. Papenfuse’s biography points out the fact that John Cary grew significantly in wealth between the time of his first election to his death. LAND AT FIRST ELECTION: 1 lot in Frederick Town, Frederick County; a house in Baltimore Town, Baltimore County (from his father's will). SIGNIFICANT CHANGES IN LAND BETWEEN FIRST ELECTION AND DEATH: acquired at least 1,665 acres in Maryland and Virginia; he and his brothers deeded their interest in their father's estate in trust to George French and Jacob Young, on Aug. 8, 1791, and then Cary sought relief as an insolvent debtor from the Assembly, which was granted on Dec. 30, 1791. WEALTH AT DEATH. Had received a warrant for 200 acres of federal land to which he was entitled for his service as a lieutenant in the Continental Army. John D. Cary ceased publishing in 1800, the same year he received his “bounty lands” for military service. Perhaps he sold them and retired on his profit margin? John P. Thomson would pick up where Cary left off with the introduction of Frederick’s new newspaper in 1802, under the name of The Frederick Town Herald. John Cary died just a few years later on October 12, 1804 in Frederick (as was reported in a Hagerstown newspaper five days later). I have, however, uncovered the “key” to a new irony and hidden connection through researching and writing this blog. It is one between our main subject, John D. Cary, and the man who gave me the impetus for it, author-historian John W. Ashbury. The fact that both men are named John is just the tip of the iceberg.  John W. Ashbury -Journalist, author, historian, mentor, friend John W. Ashbury -Journalist, author, historian, mentor, friend John Cary was an early newspaper man having familial connections to Glade Valley and the Walkersville area, not to mention a father who helped foster religion in our community. On the other hand, John Ashbury has been a lifelong newspaper columnist for several publications which include the Frederick News-Post, Baltimore Sun and the Glade Times and Mountain Mirror, with the latter serving his long-time former home of Walkersville and surrounding Glade Valley. We know that the Cary’s had a religious tie in to Frederick, what about John Ashbury? Well, John came to Frederick in 1952, when his father (Maurice Ashbury) became rector of All Saints Episcopal Church, a structure built in 1855 and located on West Church Street. Most interesting of all, the property this stately church sits on today was the original Frederick Town Lot #70—first owned by John Cary’s father, John Cary Sr.  Earlier this week the Frederick News-Post featured yet another front page story involving Trout Run, a Catoctin Mountain property where the Church of Scientology hoped to open a Narconon treatment facility. The gist of this ongoing saga centers on the news that “a Frederick County judge will decide whether the Frederick County Council acted properly last year when six members voted against a sought- after historic designation.” I have no opinion to offer here on this controversial topic, however I have to admit that I became quite fascinated with the history associated with this “non-historic” locale a few years back while performing research for a documentary on Thurmont. I bring this up solely due to the fact that it’s only fitting that this be in the paper this week. While trying to come up with a subject for my second-ever edition of the “HSP Hump Day History” blog, I stumbled over a thought-provoking, front page story lost within vintage Frederick newspaper archives. It comes from the first week of January, 1916 (100 years ago). Instead of “Trout Run,” the article that caught my imagination was about “Trout Walk.”

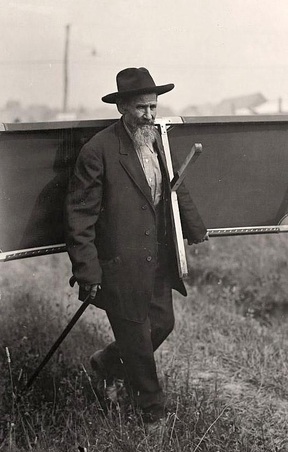

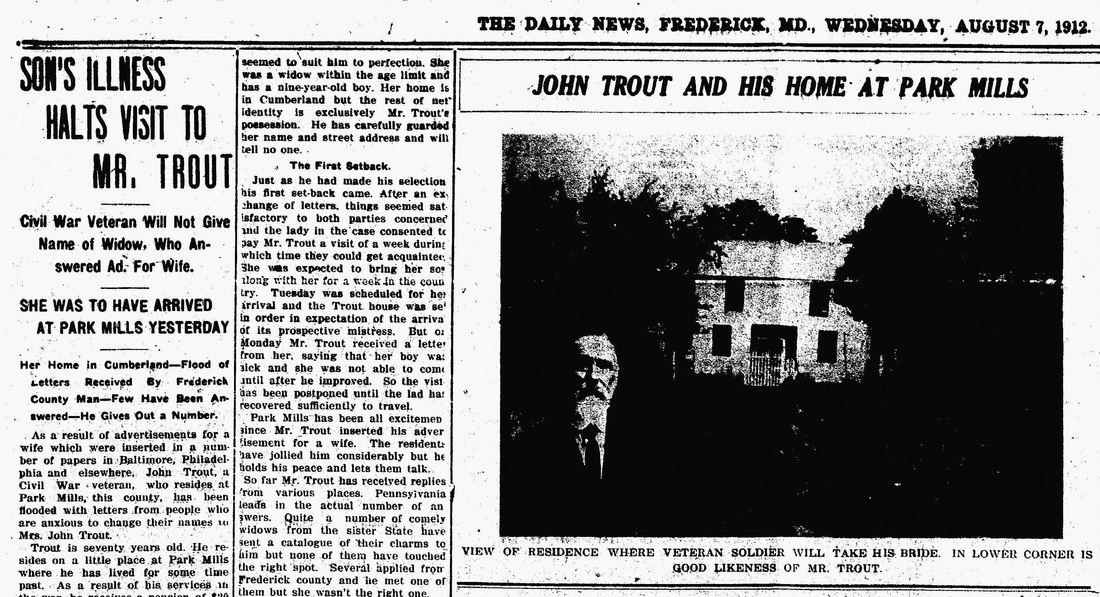

Battle of Monocacy by artist Keith Rocco, courtesy of Monocacy National Battlefield Battle of Monocacy by artist Keith Rocco, courtesy of Monocacy National Battlefield John Andrew Trout was born in Buckeystown in January, 1842. He had served as a private in Company H, 1st Potomac Home Brigade, and saw action at the nearby Battle of Monocacy on July 9, 1864. By day’s end, he would be subsequently captured by Confederate forces, and embarked on a march of more than 16 miles en-route to prison camps in Danville (VA)and later Richmond. Here he spent a period of eight months before gaining release in February 1865. Trout returned to Frederick and continued in the successful fence-making business started by his father. He married Harriet A. Baker shortly thereafter and the couple went on to have eight children. The January 8, 1916 article referenced earlier wasn’t the first newspaper appearance by the aged walker. John Trout would become a local celebrity of sorts a few years prior. In the summer of 1912, a few months after the passing of Harriet (May 1912), Mr. Trout found himself incredibly lonely after losing his spouse of 44 years. It was at this time that he concocted a remedy for his purgatorial state. He placed an advertisement in the Frederick Post (along with others in the region) looking for a new wife.

As far as I am aware, there have been no plans made for a centennial commemoration of the legendary January 1916 “Trout Walk.” However, you now will have something amusing to think about as the headlines continue in coming months as the Trout Run controversy continues to play out.

Special thanks goes out to Mr. Craig H. Trout who maintains the Find-A Grave Memorial for John Andrew Trout, a key source for this article. |

AuthorChris Haugh Archives

February 2024

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed