"My Father, My Hero"

By Chris Haugh

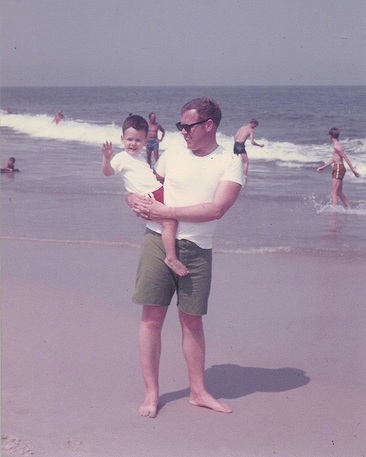

Chris and Ed Haugh at Fenwick Island, Delaware

(Summer of 1969)

Chris and Ed Haugh at Fenwick Island, Delaware

(Summer of 1969)

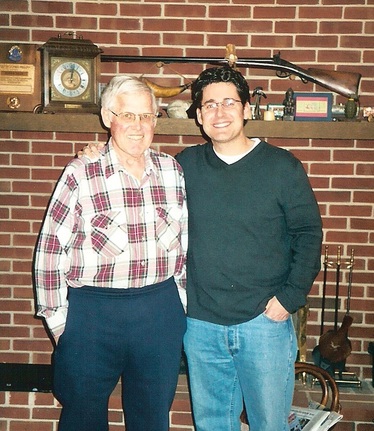

In January of 2002, my father—Edwin A. Haugh, Jr.—took the opportunity to retire from working at the age of 65. He had enjoyed nearly three decades of employment for the federal government with the National Cancer Institute, a division of the National institutes for Health. Dad had served most of his time as a technical editor for the JNCI (Journal of the National Cancer Institute), a job that appealed to him as he strove to learn more about the complicated disease that took his own father at the age of 55.

Dad took great pride in his job, hoping that someday the JNCI would carry news of a cure. Outside of that, there was nothing particularly fascinating about his work, but I recall being impressed seeing his name in bold print within the publication. He served as Managing Editor during the 1980’s.

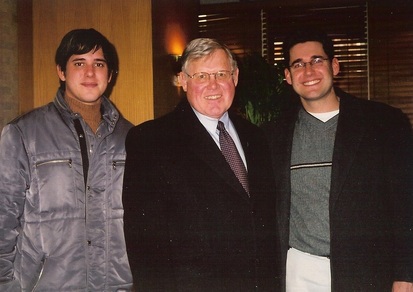

My two younger brothers (Tim and Jonathan) and I accompanied Dad to his retirement luncheon at a Hyatt Hotel in Bethesda, Maryland on a cold, blustery day. We played parts in the customary “exit parade,” carrying multiple boxes of his mementos, past papers and surplus office supplies to be placed in the trunk of his car. These “artifacts” represented the culmination of 31 years in this line of work, not to mention the sole reason for our family being uprooted from our native Delaware for Maryland.

Dad took great pride in his job, hoping that someday the JNCI would carry news of a cure. Outside of that, there was nothing particularly fascinating about his work, but I recall being impressed seeing his name in bold print within the publication. He served as Managing Editor during the 1980’s.

My two younger brothers (Tim and Jonathan) and I accompanied Dad to his retirement luncheon at a Hyatt Hotel in Bethesda, Maryland on a cold, blustery day. We played parts in the customary “exit parade,” carrying multiple boxes of his mementos, past papers and surplus office supplies to be placed in the trunk of his car. These “artifacts” represented the culmination of 31 years in this line of work, not to mention the sole reason for our family being uprooted from our native Delaware for Maryland.

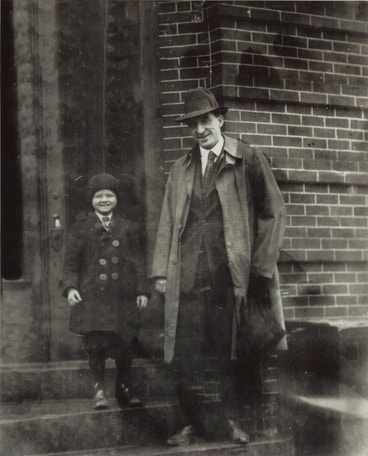

Ed Haugh's retirement luncheon with sons Jonathan (left) and Chris (right)

Ed Haugh's retirement luncheon with sons Jonathan (left) and Chris (right)

The day was joyous, yet bittersweet. My siblings and I knew how much our father would miss his fellow co-workers and the social interaction, however not the arduous hour plus commute made to and from Frederick on a daily basis. Among his chief plans for retirement––reading, spending time with his grandchildren, sightseeing and the opportunity to research family history. The latter would afford him the long-awaited chance to write on such topics as past relatives, his father’s military experiences and his hometown of Delaware City, Delaware.

Just one month into his “glorious retirement,” Dad noticed something amiss while watching television one afternoon. He began seeing dots cloud his vision. My father dismissed the issue as it went away as fast as it had appeared. However, brief episodes would occur again over the next few days day. A veteran of two earlier heart bypass surgeries, he made an immediate appointment to see his heart physician. After a few weeks of tests, my father received the surprising news that it wasn’t his heart at all––it was cancer, colon cancer.

I thought to myself, this couldn’t be, because he had just had a colonoscopy a couple years before. However, his gastroenterologist would later tell me that Dad’s insurance plan (at the time) had only covered a partial colonoscopy—called a sigmoidoscopy. The infected area in question had lain undetected. Immediate plans were made to remove the polyp-riddled section of the colon in hopes to rid his body of the disease that he had devoted most of his working career toward. Dad remained optimistic, and kept a sense of humor, and how could he not as he had been referred to a surgeon named Dr. Hurtt.

Dr. Kevin Hurtt was successful in removing the infected section of colon. Dad’s immediate recovery from surgery was equally prosperous. During this same time period (March 2002), a second grandchild named Collin was born to my brother Tim and sister-in-law Sara. Dad joked that Tim likely chose this name as a tribute to his colon which had been stealing much of the family headlines of late. Unfortunately, the jubilation of Collin’s arrival was tempered with the reality that my father was diagnosed with stage III colon cancer––the disease had spread through the lymph nodes already. Estimates said he had roughly a 65% chance to beat it.

Just one month into his “glorious retirement,” Dad noticed something amiss while watching television one afternoon. He began seeing dots cloud his vision. My father dismissed the issue as it went away as fast as it had appeared. However, brief episodes would occur again over the next few days day. A veteran of two earlier heart bypass surgeries, he made an immediate appointment to see his heart physician. After a few weeks of tests, my father received the surprising news that it wasn’t his heart at all––it was cancer, colon cancer.

I thought to myself, this couldn’t be, because he had just had a colonoscopy a couple years before. However, his gastroenterologist would later tell me that Dad’s insurance plan (at the time) had only covered a partial colonoscopy—called a sigmoidoscopy. The infected area in question had lain undetected. Immediate plans were made to remove the polyp-riddled section of the colon in hopes to rid his body of the disease that he had devoted most of his working career toward. Dad remained optimistic, and kept a sense of humor, and how could he not as he had been referred to a surgeon named Dr. Hurtt.

Dr. Kevin Hurtt was successful in removing the infected section of colon. Dad’s immediate recovery from surgery was equally prosperous. During this same time period (March 2002), a second grandchild named Collin was born to my brother Tim and sister-in-law Sara. Dad joked that Tim likely chose this name as a tribute to his colon which had been stealing much of the family headlines of late. Unfortunately, the jubilation of Collin’s arrival was tempered with the reality that my father was diagnosed with stage III colon cancer––the disease had spread through the lymph nodes already. Estimates said he had roughly a 65% chance to beat it.

A subsequent spring and summer of relaxation in retirement quickly turned into regular clinic visits. The opportunity to experience sensations of excitement tied to family heritage discoveries and field exploration were replaced with days in bed and feelings of nausea courtesy of chemotherapy. My father was a trooper, but this medical blow certainly derailed most of Dad’s “big plans.” Then, out of nowhere, he suddenly became interested in a peaceful deterrent—model railroading.

Dad began spending his time researching, purchasing and setting up O-Scale train accessories and began setting them up in the living room of his house—my childhood home. This brought my father great happiness amid a depressing health climate. My brothers and I began purchasing unique train cars to add to his newfound collection. The tranquility this new hobby provided not only took his mind off the cancer, but reminded him of introducing trains to me in younger years. More importantly, this activity beckoned fond memories from his own childhood in which he had an extensive model train collection and track layout—an activity he greatly enjoyed doing with his own father.

Dad began spending his time researching, purchasing and setting up O-Scale train accessories and began setting them up in the living room of his house—my childhood home. This brought my father great happiness amid a depressing health climate. My brothers and I began purchasing unique train cars to add to his newfound collection. The tranquility this new hobby provided not only took his mind off the cancer, but reminded him of introducing trains to me in younger years. More importantly, this activity beckoned fond memories from his own childhood in which he had an extensive model train collection and track layout—an activity he greatly enjoyed doing with his own father.

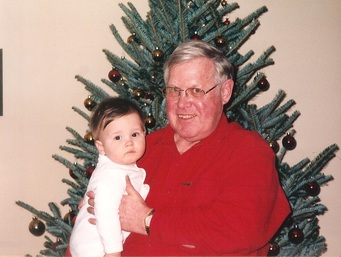

Granddad and Collin, Christmas, 2002

Granddad and Collin, Christmas, 2002

Thanksgiving and Christmas of 2002 were amazing occasions, and my siblings and I were certainly thankful for our father’s subsequent medical well-being after going through a major surgery and round of chemotherapy. We prayed that this remission period would continue indefinitely. Dad outdid himself that holiday by purchasing an overabundance of presents for all of us, while he was the recipient of additional train cars and related "hobby railroading"supplies.

Now being able to relax a little from the stress of weathering another parental health ordeal, I felt an inner urge to help my father get back on track with more than just his train set. I wanted to see Dad embark on his research and writing quests. At the same time, I needed to learn more about my father, his family and his life journey. In my current career with a local television production entity, I had spent the previous ten years producing documentaries and programs about my hometown of Frederick and the various citizens and history topics related to the surrounding region. In addition to historians and authors, I had interviewed dozens of people on-camera about their humble lives here. It was now time to do something that had direct implications on my own existence. Perhaps it was a selfish urge, but I felt as if I had dodged a potent bullet myself—almost losing one of my parents, the two best historical resources on my own existence.

Now being able to relax a little from the stress of weathering another parental health ordeal, I felt an inner urge to help my father get back on track with more than just his train set. I wanted to see Dad embark on his research and writing quests. At the same time, I needed to learn more about my father, his family and his life journey. In my current career with a local television production entity, I had spent the previous ten years producing documentaries and programs about my hometown of Frederick and the various citizens and history topics related to the surrounding region. In addition to historians and authors, I had interviewed dozens of people on-camera about their humble lives here. It was now time to do something that had direct implications on my own existence. Perhaps it was a selfish urge, but I felt as if I had dodged a potent bullet myself—almost losing one of my parents, the two best historical resources on my own existence.

Edwin A. "Eddie" Haugh, Jr. with parents Edwin A. and Margaret (Warfel) Haugh (c.1945)

Edwin A. "Eddie" Haugh, Jr. with parents Edwin A. and Margaret (Warfel) Haugh (c.1945)

I naturally started on my father's heritage, as I could tackle my mother’s background later. I began asking Dad about what he knew of his family lineage, and pleaded with him to recant stories I recalled hearing in my childhood. My knowledge of Dad’s relatives included characters consisting of both fact and, quite possibly, a bit of fiction:

*A mother who barely finished school and gave birth to him at the age of 18, but went on to successfully operate a small grocery store until her death, all the while claiming she didn’t know much more than “the price of potatoes”

*A father who had worked his entire career in the US Army, serving with distinction in Europe during World War II before being captured by the Germans and spending months in POW camps.

*A GG Grandfather hailing from Germany in the 1840’s, a carpenter by trade and said to be a Civil War guard at the infamous Fort Delaware Union prison garrison

*A GG Grandmother from Alsace-Lorraine who arrived in the 1850’s as a teen after smuggling her father and uncle out of the country in the back of a hay wagon, all the while disguised as a boy

*Another GG Grandfather from Delaware County, Indiana who allegedly served as a cavalry scout who once rode alongside Buffalo Bill

*Grandfather “Al” Haugh, a leading newspaperman for the Philadelphia area, who covered the sensational Lindberg baby kidnapping trial

*A great uncle who had been accidentally shot as a young boy, while harmlessly sitting in the front parlor of his house by a man who was hunting along the canal

*One grandmother lovingly called “Apple Granny” due to an abundance of hedge apples on her farm, and another grandmother labeled with the moniker “Crazy Jennie”

*A grandfather named Herman Warfel, a quiet and stern former veteran, ambulance driver and farmer who apparently was hired by the US government to help bust up a British smuggling ring during the Prohibition era

*A mother who barely finished school and gave birth to him at the age of 18, but went on to successfully operate a small grocery store until her death, all the while claiming she didn’t know much more than “the price of potatoes”

*A father who had worked his entire career in the US Army, serving with distinction in Europe during World War II before being captured by the Germans and spending months in POW camps.

*A GG Grandfather hailing from Germany in the 1840’s, a carpenter by trade and said to be a Civil War guard at the infamous Fort Delaware Union prison garrison

*A GG Grandmother from Alsace-Lorraine who arrived in the 1850’s as a teen after smuggling her father and uncle out of the country in the back of a hay wagon, all the while disguised as a boy

*Another GG Grandfather from Delaware County, Indiana who allegedly served as a cavalry scout who once rode alongside Buffalo Bill

*Grandfather “Al” Haugh, a leading newspaperman for the Philadelphia area, who covered the sensational Lindberg baby kidnapping trial

*A great uncle who had been accidentally shot as a young boy, while harmlessly sitting in the front parlor of his house by a man who was hunting along the canal

*One grandmother lovingly called “Apple Granny” due to an abundance of hedge apples on her farm, and another grandmother labeled with the moniker “Crazy Jennie”

*A grandfather named Herman Warfel, a quiet and stern former veteran, ambulance driver and farmer who apparently was hired by the US government to help bust up a British smuggling ring during the Prohibition era

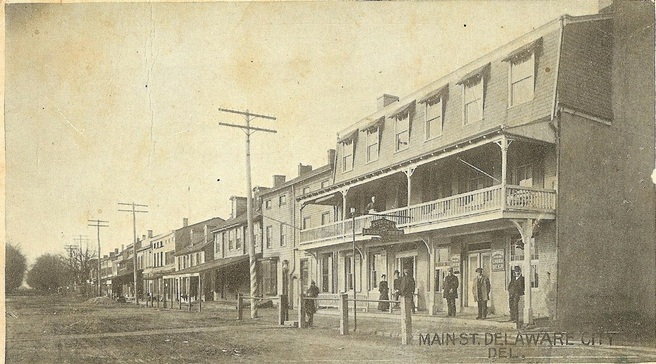

Clinton Street in Delaware City (c.1905)

Clinton Street in Delaware City (c.1905)

Edwin A. Haugh, Jr. was the family expert on his mother’s mother side, a four-generation line that lived and died in the small river port town of Delaware City, Delaware. I did a great deal of family research on these people in 2003, and my study still continues today when afforded the opportunity. At that time, I was able to share a few new tidbits with my dad, adding to, and corroborating many of his family stories pertaining to the Koch (anglicized to Cook) family line.

Edwin A. Haugh, Sr. and his father Ambrose "Al" Haugh in front of the Camden Courier-Post building in Camden, NJ (c.1920)

Edwin A. Haugh, Sr. and his father Ambrose "Al" Haugh in front of the Camden Courier-Post building in Camden, NJ (c.1920)

I also navigated into unchartered territory relating to Dad’s little-known paternal Haugh side. I made several trips to the Camden Historical Society in Camden, New Jersey. Here, I scoured microfilm of the Camden Evening Post and Courier newspapers of which my great-grandfather Albert Ambrose "Al" Haugh was editor during the 1920's and into the 1930's. My greatest achievement came in discovering that our Haugh family roots were connected to Europe through Al's father, a man named Ambrose Jason Haugh (1854-1927). Ambrose came to America in the early 1870’s, hailing from a small town in Waterford County, Ireland. This was big news, because we had always been under the impression that our ancestors came directly from Scotland. I quickly found myself piecing together parts of our surname like a paleontologist reconstructing dinosaur fossils.

By year’s end, I found myself doing the ancestral “heavy lifting” for my dad, while he could relax and revel in my triumphs. We had even taken a weekend road trip that summer to Delaware and New Jersey, finding his grandfather Haugh’s gravesite near his father’s childhood home of Audubon, New Jersey. He had never seen it before, sufficed to say, nobody really had because it had remained unmarked since the newspaper veteran's death in November, 1936. This was just two months after my father was born. We were ecstatic to learn that this same plot was also the final resting place of my father’s grandmother (the earlier mentioned “Crazy Jennie") and Irish immigrant Ambrose Jason Haugh, Al’s father.

By year’s end, I found myself doing the ancestral “heavy lifting” for my dad, while he could relax and revel in my triumphs. We had even taken a weekend road trip that summer to Delaware and New Jersey, finding his grandfather Haugh’s gravesite near his father’s childhood home of Audubon, New Jersey. He had never seen it before, sufficed to say, nobody really had because it had remained unmarked since the newspaper veteran's death in November, 1936. This was just two months after my father was born. We were ecstatic to learn that this same plot was also the final resting place of my father’s grandmother (the earlier mentioned “Crazy Jennie") and Irish immigrant Ambrose Jason Haugh, Al’s father.

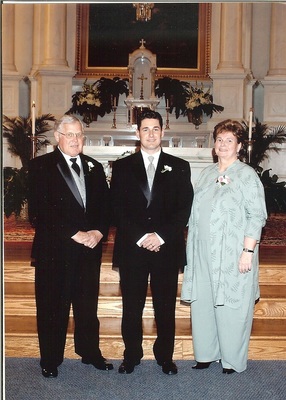

Wedding Day with both my parents (September 2003)

Wedding Day with both my parents (September 2003)

As is the case with many cancer patients, a period of subsequent remission was followed by a resurgence of the disease, requiring another round of chemotherapy in the spring/summer of 2003. This time around, however, a couple of spots were found on Dad’s liver. The stress was building in me. My father’s health issues were paramount of course, but I found myself constantly ”fighting fires” with my job for a failing cable television company (Adelphia Communications), working on family genealogy, and planning a wedding and honeymoon scheduled for late September, 2003.

Luckily, I was successful in juggling all of these things, and kudos go out to my fiancée who kept me in one piece. The marriage was a great, and welcome, distraction for Dad—clearly something to look forward too. He even insisted on hosting the rehearsal dinner at his house, which he did. All went off swimmingly, propelling us into another holiday season.

My brothers and I planned, and offered, to take Dad to Ireland for a Christmas present—one place he had never been, and had the great desire to see. In particular, I now wanted to get him to Waterford County, the ancestral home of the aforementioned Ambrose Jason Haugh. My father was very excited about the prospect, but cautioned us not to make any travel purchases and plans until he received clearance to travel by his physician. We began talking of a potential spring visit.

Luckily, I was successful in juggling all of these things, and kudos go out to my fiancée who kept me in one piece. The marriage was a great, and welcome, distraction for Dad—clearly something to look forward too. He even insisted on hosting the rehearsal dinner at his house, which he did. All went off swimmingly, propelling us into another holiday season.

My brothers and I planned, and offered, to take Dad to Ireland for a Christmas present—one place he had never been, and had the great desire to see. In particular, I now wanted to get him to Waterford County, the ancestral home of the aforementioned Ambrose Jason Haugh. My father was very excited about the prospect, but cautioned us not to make any travel purchases and plans until he received clearance to travel by his physician. We began talking of a potential spring visit.

In late January (2004), I accompanied my father to Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore to meet with a leading cancer physician. With his chemotherapy rounds, Dad had called on former work colleagues for references to help him participate in clinical trials utilizing experimental drugs. Without focus on his own situation, he still wanted to do all he could in the quest for finding a cure.

While I had my mind set on an upcoming vacation in the British Isles, news from Dad’s physician on this day would blindside me. A medical assistant found me in the waiting area, saying that the doctor needed to speak to me. I soon joined the doctor and my dad in the exam room. The physician announced that the second round of chemotherapy had been unsuccessful—the cancer was still on the move, already having infiltrated other vital organs and now tumors had formed on the outside of his colon. There would be another round of chemotherapy, but the prognosis was grim. My Dad knew too much about this disease, bliss ignorance could not be employed in his case. The doctor told us that he’d be lucky to make it through the year.

We drove home from Baltimore that day saying nothing to each other at all. Once inside his house, he took a seat in his favorite dark blue recliner chair and I sat directly across from him, struggling to find the right words to say. He looked at me and blurted out calmly, “I’m not afraid to die. “ My father had demonstrated a valiant front over the past 23 months, his well-deserved retirement. He would now tell me that he was forever linked to cancer, as this is what took his father from this world and eventually giving him the impetus to take the job with NCI in the first place. As history was repeating itself, I now saw cancer taking my father from me. Dad found his job efforts as more of a dedication to his own father, with the opportunity to take part in ridding the world of the horrible disease.

I sat mesmerized. After a long pause and stoic stare, my father next said, “What I will miss most is seeing my grandchildren grow up. “ (My brother also had another son, Tyler, born in 1999.) With this, he began to cry, a rare site coming from a man who rarely showed raw emotion, something I had only witnessed twice before with the death of his mother in 1987, and again early the next year on the day our parents announced that they were separating. Dad has been best described as having been “a gentle man,” truly a laid back, even-tempered individual. I immediately went over to him and gave him a long hug, and told him how truly sorry I was that he had to endure all of this. I also told him how proud we were of the way he was handling all that had come with his illness. He calmly told me that he needed time to be alone, and would call me later in better spirits.

The next day, I got the request asking if I could help my father with a few organizational tasks. That evening, after work, we moved some furniture around and he gave me a list of items to purchase. These included: a new television for his bedroom, specific novels to read, plastic storage tubs, a three-door metal file cabinet, and file folders. He also outlined specific home and long overdue yard repairs that needed to be carried out. My father specifically wanted to get things such as important paperwork, valued heirlooms, and miscellaneous junk organized for me. He wanted to make his final months less cluttered, and my job as imminent estate executor as seamless as possible.

That’s when I told him, “You know what I want you to do for me— for us? “

He replied, “What?”

I said, “I need to interview you on tape.”

And he said, “I knew you would ask me to.“

While I had my mind set on an upcoming vacation in the British Isles, news from Dad’s physician on this day would blindside me. A medical assistant found me in the waiting area, saying that the doctor needed to speak to me. I soon joined the doctor and my dad in the exam room. The physician announced that the second round of chemotherapy had been unsuccessful—the cancer was still on the move, already having infiltrated other vital organs and now tumors had formed on the outside of his colon. There would be another round of chemotherapy, but the prognosis was grim. My Dad knew too much about this disease, bliss ignorance could not be employed in his case. The doctor told us that he’d be lucky to make it through the year.

We drove home from Baltimore that day saying nothing to each other at all. Once inside his house, he took a seat in his favorite dark blue recliner chair and I sat directly across from him, struggling to find the right words to say. He looked at me and blurted out calmly, “I’m not afraid to die. “ My father had demonstrated a valiant front over the past 23 months, his well-deserved retirement. He would now tell me that he was forever linked to cancer, as this is what took his father from this world and eventually giving him the impetus to take the job with NCI in the first place. As history was repeating itself, I now saw cancer taking my father from me. Dad found his job efforts as more of a dedication to his own father, with the opportunity to take part in ridding the world of the horrible disease.

I sat mesmerized. After a long pause and stoic stare, my father next said, “What I will miss most is seeing my grandchildren grow up. “ (My brother also had another son, Tyler, born in 1999.) With this, he began to cry, a rare site coming from a man who rarely showed raw emotion, something I had only witnessed twice before with the death of his mother in 1987, and again early the next year on the day our parents announced that they were separating. Dad has been best described as having been “a gentle man,” truly a laid back, even-tempered individual. I immediately went over to him and gave him a long hug, and told him how truly sorry I was that he had to endure all of this. I also told him how proud we were of the way he was handling all that had come with his illness. He calmly told me that he needed time to be alone, and would call me later in better spirits.

The next day, I got the request asking if I could help my father with a few organizational tasks. That evening, after work, we moved some furniture around and he gave me a list of items to purchase. These included: a new television for his bedroom, specific novels to read, plastic storage tubs, a three-door metal file cabinet, and file folders. He also outlined specific home and long overdue yard repairs that needed to be carried out. My father specifically wanted to get things such as important paperwork, valued heirlooms, and miscellaneous junk organized for me. He wanted to make his final months less cluttered, and my job as imminent estate executor as seamless as possible.

That’s when I told him, “You know what I want you to do for me— for us? “

He replied, “What?”

I said, “I need to interview you on tape.”

And he said, “I knew you would ask me to.“

Filming the interview, early March, 2004.

Filming the interview, early March, 2004.

I stayed up particularly late that night along with the next few, busily drawing up an interview outline, complete with pertinent topics and questions. This was followed by the creation of a multi-week plan of video-taping sessions. I certainly knew the importance of this undertaking and was not treating it lightly.

I prepared my father for each interview session in advance, emailing him breakdowns of subject areas and providing outlines with specific questions. This allowed him to jumpstart his thought process, as much of this information had been tucked neatly away in his mind for years, even decades. He had the time to get his thoughts and stories in order, the next best thing to a dress rehearsal. I chose to set up the interview in my dad’s den/family room, a place that had provided so many great memories for my siblings and I since moving to Frederick and this house exactly 30 years earlier.

Filming began on February 21st. I did have to perform a little rearranging of furniture and accoutrements in an effort to have an ideal backdrop while also accommodating my video camera, tripod, audio and lighting equipment. Just out of camera shot, a side table provided my Dad a surface for his notes. Best of all, he could stay in his sweatpants and slippers since I was only filming him from the waist up.

I prepared my father for each interview session in advance, emailing him breakdowns of subject areas and providing outlines with specific questions. This allowed him to jumpstart his thought process, as much of this information had been tucked neatly away in his mind for years, even decades. He had the time to get his thoughts and stories in order, the next best thing to a dress rehearsal. I chose to set up the interview in my dad’s den/family room, a place that had provided so many great memories for my siblings and I since moving to Frederick and this house exactly 30 years earlier.

Filming began on February 21st. I did have to perform a little rearranging of furniture and accoutrements in an effort to have an ideal backdrop while also accommodating my video camera, tripod, audio and lighting equipment. Just out of camera shot, a side table provided my Dad a surface for his notes. Best of all, he could stay in his sweatpants and slippers since I was only filming him from the waist up.

Eddie Haugh at 14 years old in photo taken while living in Bremen Germany (March 1951)

Eddie Haugh at 14 years old in photo taken while living in Bremen Germany (March 1951)

We did eight interview sessions, garnering upwards of 17 hours of material including everything from well-known, shared family stories to a cavalcade of childhood memories painting wonderful character sketches of his parents, grandparents, cousins and friends. I learned so much about life in his hometown of Delaware City, multiple schools he attended, and the various places his father’s Army assignments would take the family. Most fascinating of these was the two years spent in allied occupied Germany after World War II. This was in the town of Bremen in northern Germany, and he told me of his daily hour and half commute each way to and from an American school in Bremerhaven on the coast of the North Sea. He would attend both 9th and 10th grades here, serving as class president his sophomore year.

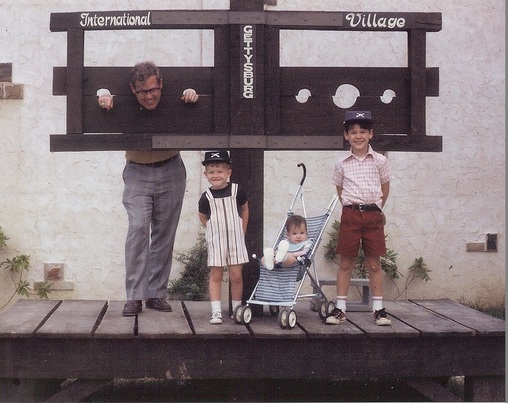

Interest in history was influenced by early childhood trips to places like nearby Gettysburg. (L-R) Ed, Tim, Jonathan and Chris (September, 1974)

Interest in history was influenced by early childhood trips to places like nearby Gettysburg. (L-R) Ed, Tim, Jonathan and Chris (September, 1974)

From there we tackled high school graduation back in the states, adventures with friends and cousins, dating, college, early jobs, how he met my mother, raising a family, multiple moves including coming to Frederick in 1974, his career at NCI, family vacations, and all the way up to the present day including candid praise and summations of each of his children. It was great to hear stories about me through the years, as he was an authority and key “eyewitness” to my life as much as his own.

I interviewed my dad from a third person perspective, forcing him to include intricate detail, avoiding the pitfall for abbreviated anecdotes or fragmented stories. This can easily occur when the interviewee assumes the interviewer knows the details already. However, not every viewer in the future will be armed with the backstories and “obvious” knowledge of the time and characters involved.

My father was simply magnificent! By the last session on March 12th, I had learned more about this man in less than three weeks than I had ever known in my 37 years as his son. With appropriate passion, enthusiasm and often times, humor, he recollected his previous 67 years, along with the life and times of his parents and what he could remember, or had been told, regarding his grandparents and earlier ancestors.

Of particular note, I had captured on film a highly emotional and memorable moment from his childhood—one that would leave an indelible impression for the rest of his life. This pertained to World War II, a time in which he and his mother moved in with his grandparents on their farm. His Aunt Betty, (mother’s sister) had done the same. Both sisters’ husbands were away at war overseas, as was their younger brother Robert “Bobby” Warfel.

I interviewed my dad from a third person perspective, forcing him to include intricate detail, avoiding the pitfall for abbreviated anecdotes or fragmented stories. This can easily occur when the interviewee assumes the interviewer knows the details already. However, not every viewer in the future will be armed with the backstories and “obvious” knowledge of the time and characters involved.

My father was simply magnificent! By the last session on March 12th, I had learned more about this man in less than three weeks than I had ever known in my 37 years as his son. With appropriate passion, enthusiasm and often times, humor, he recollected his previous 67 years, along with the life and times of his parents and what he could remember, or had been told, regarding his grandparents and earlier ancestors.

Of particular note, I had captured on film a highly emotional and memorable moment from his childhood—one that would leave an indelible impression for the rest of his life. This pertained to World War II, a time in which he and his mother moved in with his grandparents on their farm. His Aunt Betty, (mother’s sister) had done the same. Both sisters’ husbands were away at war overseas, as was their younger brother Robert “Bobby” Warfel.

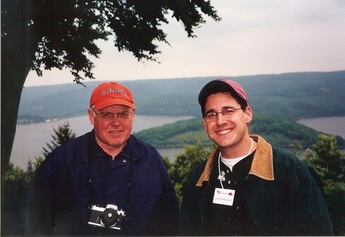

Standing on the heights of the Roer River near the site of the Schwammenauel Dam and village of Schmidt in western Germany near the border of Belgium (June 2004)

Standing on the heights of the Roer River near the site of the Schwammenauel Dam and village of Schmidt in western Germany near the border of Belgium (June 2004)

I certainly received a more realistic sense of this period in American history, a departure from the battlefield strategies and heroics that usually come to mind in recalling unbridled patriotism and larger than life heroes from “the Greatest Generation.” I had a strong introduction to this subject matter (World War II) having accompanied my father on a European battlefield tour back in 2001. Here we had the chance to trace the steps of my grandfather’s 78th Infantry Division unit across Belgium and into Germany.

The trip was sponsored by the 78th Division Veterans Association and the majority of participants were WWII veterans and their spouses. I was the youngest person on the trip, my father was a close second. Of course I had my video camera and documented the whole thing.

The trip was sponsored by the 78th Division Veterans Association and the majority of participants were WWII veterans and their spouses. I was the youngest person on the trip, my father was a close second. Of course I had my video camera and documented the whole thing.

Grave of Bobby Warfel, Lorraine American Cemetery, St. Avold, France. (June 2001)

Grave of Bobby Warfel, Lorraine American Cemetery, St. Avold, France. (June 2001)

On this trip, we also visited Normandy, France. Dad and I walked across Omaha Beach and visited places such as Pointe du Hoc, St. Mere Eglise, Pegasus Bridge and numerous American military cemeteries. We stayed for an extra few days, rented a car, and toured Bastogne and sites of earlier famed conflicts such as Verdun (World War I) and Waterloo, site of Wellington’s legendary defeat of Napoleon in 1815. The most memorable site on this final leg of our trip was located in eastern France near a town named St. Avold. Here we visited Lorraine American Cemetery, final resting place of my father’s Uncle Bobby (Warfel).

My dad was very solemn during that particular visit, as one would certainly expect. Earlier he had told me how his uncle was part of the 778th Tank Division and one day helped a fellow soldier by taking his turn to scout out the situation of the tank’s location in relation to the surrounding area. When he popped his head out of the hatch (of the tank) to look out, he was mowed down by a sniper’s bullet—he died within minutes. Bobby Warfel was just 22 years old.

With the help of Army headquarters’ reports and maps, we actually found and walked the exact ground where my great uncle had been gunned down. I had my Dad tell this tale on camera for me during the 2004 interview and quite surprised and moved when he shared a related account from his family on the Delaware home front.

My dad was very solemn during that particular visit, as one would certainly expect. Earlier he had told me how his uncle was part of the 778th Tank Division and one day helped a fellow soldier by taking his turn to scout out the situation of the tank’s location in relation to the surrounding area. When he popped his head out of the hatch (of the tank) to look out, he was mowed down by a sniper’s bullet—he died within minutes. Bobby Warfel was just 22 years old.

With the help of Army headquarters’ reports and maps, we actually found and walked the exact ground where my great uncle had been gunned down. I had my Dad tell this tale on camera for me during the 2004 interview and quite surprised and moved when he shared a related account from his family on the Delaware home front.

Tch 4 Robert "Bobby" Warfel on right (early 1944)

Tch 4 Robert "Bobby" Warfel on right (early 1944)

I had asked the question, “What was life like during the war, knowing that your father was overseas and in the face of danger?” I had found this question particularly interesting due to his age at the time (8), and that of his 31 year-old father (in 1944)—both older than the norm. Most children of servicemen in the war were generally too young to remember anything of great detail. This question would trigger the greatest emotional response I had ever seen come out of him.

My father said that he and his family were scared, very scared. The family received word that Staff Sgt. Edwin A. Haugh, Sr. was MIA (Missing in Action) in late December, 1944—Christmastime. The news struck hard, but they had already been numbed by worse information exactly one month earlier around Thanksgiving. I asked myself what could be worse?—and soon found out.

Dad vividly recalled sitting alone on his grandfather Warfel’s lap, as they were rocking and singing old Army ditties in the dark living room of the farmhouse. It was a pleasant, unusually warm afternoon for that time of year. A car became visible in the distance and slowly made its way up the long lane. It was Margie Netsch, the local telegraph operator who worked at the local drugstore. Dad’s grandfather softly lifted my father out of his lap and placed him aside the rocker. He went to greet Ms. Netsch at the car. She shared with him a telegram carrying word that Bobby had been killed. His mild-mannered grandfather was now overflowing with emotion as he began calling wildly for his wife Zitta, screaming, “Mama, Mama...Bobby’s dead… Bobby’s dead!” He met my great grandmother on the front porch with tears streaming down his face, and buried his head into her shoulder. Dad recalled that it was the one and only time he had ever seen his grandfather cry. His grandfather would sit quietly by himself in the gloomy front room for the rest of that afternoon and into the evening, passing on supper as well. In addition, my father would also be surrounded by Bobby’s devastated mother and two grieving siblings—both of whom had spouses abroad on the warfront.

It actually took my father four separate “takes” on camera to convey this heartbreaking story to me…each time overtaken by grief and sadness until he finally regained full composure. I thought to myself, What a life moment for him, especially compacted with the possibility that his own father may be next.

This was my father's first true experience of losing someone close to him—and it wasn’t the typical aged relative who had led a good life and being told by adults that it was their time to go. This was a vibrant young man, an idol of sorts to my father, and someone only 14 years his elder. From my perspective, this anecdote still serves as my most memorable moment in videography—hard to watch, but I knew real-time that I was experiencing a visit into something deeper than my father’s mind and heart, this was a journey into his soul, and I preserved it for posterity.

My father said that he and his family were scared, very scared. The family received word that Staff Sgt. Edwin A. Haugh, Sr. was MIA (Missing in Action) in late December, 1944—Christmastime. The news struck hard, but they had already been numbed by worse information exactly one month earlier around Thanksgiving. I asked myself what could be worse?—and soon found out.

Dad vividly recalled sitting alone on his grandfather Warfel’s lap, as they were rocking and singing old Army ditties in the dark living room of the farmhouse. It was a pleasant, unusually warm afternoon for that time of year. A car became visible in the distance and slowly made its way up the long lane. It was Margie Netsch, the local telegraph operator who worked at the local drugstore. Dad’s grandfather softly lifted my father out of his lap and placed him aside the rocker. He went to greet Ms. Netsch at the car. She shared with him a telegram carrying word that Bobby had been killed. His mild-mannered grandfather was now overflowing with emotion as he began calling wildly for his wife Zitta, screaming, “Mama, Mama...Bobby’s dead… Bobby’s dead!” He met my great grandmother on the front porch with tears streaming down his face, and buried his head into her shoulder. Dad recalled that it was the one and only time he had ever seen his grandfather cry. His grandfather would sit quietly by himself in the gloomy front room for the rest of that afternoon and into the evening, passing on supper as well. In addition, my father would also be surrounded by Bobby’s devastated mother and two grieving siblings—both of whom had spouses abroad on the warfront.

It actually took my father four separate “takes” on camera to convey this heartbreaking story to me…each time overtaken by grief and sadness until he finally regained full composure. I thought to myself, What a life moment for him, especially compacted with the possibility that his own father may be next.

This was my father's first true experience of losing someone close to him—and it wasn’t the typical aged relative who had led a good life and being told by adults that it was their time to go. This was a vibrant young man, an idol of sorts to my father, and someone only 14 years his elder. From my perspective, this anecdote still serves as my most memorable moment in videography—hard to watch, but I knew real-time that I was experiencing a visit into something deeper than my father’s mind and heart, this was a journey into his soul, and I preserved it for posterity.

"It's a Wrap!" End of interview session, March 2004

"It's a Wrap!" End of interview session, March 2004

The second most memorable moment for me in this video documentation project came with my last and final question. It really wasn’t the question, itself, but more so my realization that the interview was coming to a close. Yes, I was happy to have accomplished this time-consuming task, however I would be overwhelmed with a sudden feeling of sadness. This was a metaphoric response of course, as I knew that this interview represented the story of Edwin A. Haugh Jr.’s life. I was now on the literal final page, and reading the last few sentences knowing that I was fast approaching the traditional close of “THE END.” Meanwhile, my subject's life on Earth was doing the same.

By most people’s account, my father’s life story would be rated ordinary, average, and humble… but one that I am so thankful to have played a major role in. The entire interview exercise reaffirmed the hope and security I had in myself, with the underlying message that I need not have fear for living my next 30+ years to equal his 67. His many stories were reminders of this fact, and had always been so, dating back to when I was a child and told these by my parents and grandparents. On the other side, Dad was very pleased to assist me with this unique gift of history and biographic documentation. He had provided something that could be shared among his sons, grandchildren and generations to follow. I converted the videotapes from those sessions to dvds, and to this day they continue to serve among my most prized possessions.

By most people’s account, my father’s life story would be rated ordinary, average, and humble… but one that I am so thankful to have played a major role in. The entire interview exercise reaffirmed the hope and security I had in myself, with the underlying message that I need not have fear for living my next 30+ years to equal his 67. His many stories were reminders of this fact, and had always been so, dating back to when I was a child and told these by my parents and grandparents. On the other side, Dad was very pleased to assist me with this unique gift of history and biographic documentation. He had provided something that could be shared among his sons, grandchildren and generations to follow. I converted the videotapes from those sessions to dvds, and to this day they continue to serve among my most prized possessions.

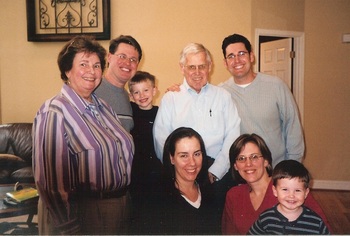

Ed and family, Easter (April 11) 2004

Ed and family, Easter (April 11) 2004

Throughout March and April, I went through showings of old family slide shows with my dad, still asking questions and taking notes. I had most of the content already recorded on tape through the interviews, but now I was compiling illustrations and visual identification of holidays, special events and vacations to accompany the stories. We also reviewed family heirlooms, memorabilia and antiques, which I documented on camera with his spoken narration.

By Easter, my father was considerably weakened, having lost a great deal of weight due to an overall lack of appetite. In early May, I planned a big cookout at my house for my dad, but unfortunately the guest of honor couldn't make it in town as he was too sick to attend. So my home served as a base in which folks took turns driving out to his house to visit him. Dad called me that night to specifically thank me for all I had done in arranging such a nice day for him and everybody.

A few weeks later, I traveled to Delaware to take pictures and borrow family photo albums from distant cousins. I now found myself sitting bedside with Dad, having him describe pictures and events to the best of his ability. This was also my chance to document and properly label and organize these heirlooms, an entire process that was bringing considerable comfort and joy to my father in his deteriorating state. He was remembering happy times in an earlier age, seeing his parents and a cavalcade of other relatives and friends who had passed years before.

Hospice Care at home was called for in early June, along with a schedule of round the clock vigil shifts spent by us his immediate family members. My mother, his ex-wife, also unselfishly participated in this regimen. I recall many things from that time period, but two things I will share here. My dad asked one of the Hospice workers, a young lady, when her due date would be. I was somewhat embarrassed because I couldn't even tell if she as pregnant or not. She seemed quite surprised, yet flattered by the question, and explained that she and her husband had just found out a few weeks before and were in the process of telling family and friends. She questioned my father how he knew she was pregnant? He replied that he could tell by the special glow she gave off. She was touched, and he wished her the best of luck and happiness as a mother into the future.

On June 8th I was covering an overnight shift, actually sleeping in a chair by my father's bedside. I was abruptly awoken around 3am in the morning by my dad talking to someone. He was actually still asleep and appeared to be talking to his mother about his day at school. I was floored by this and listened intently for the short time it lasted. About an hour later, he remained asleep but asked the question: "Chris, what do you want for Christmas this year?" I told him that he could get me whatever he wanted. He retorted back a list of possible items, all toys from my childhood. Words can't put into words how amazing this experience was.

I vividly remember Friday, June 11th as the day Hospice staff moved Dad from his upstairs bedroom to the living room on the main level. Ronald Reagan’s State funeral was on the television in the other room. My father, a devoted Reagan supporter and fan, shared sympathy, but had no desire to watch. Fifty-five hours later, my father would breathe his last breath during the early morning hours of Flag Day, Monday, June 14, 2004.

By Easter, my father was considerably weakened, having lost a great deal of weight due to an overall lack of appetite. In early May, I planned a big cookout at my house for my dad, but unfortunately the guest of honor couldn't make it in town as he was too sick to attend. So my home served as a base in which folks took turns driving out to his house to visit him. Dad called me that night to specifically thank me for all I had done in arranging such a nice day for him and everybody.

A few weeks later, I traveled to Delaware to take pictures and borrow family photo albums from distant cousins. I now found myself sitting bedside with Dad, having him describe pictures and events to the best of his ability. This was also my chance to document and properly label and organize these heirlooms, an entire process that was bringing considerable comfort and joy to my father in his deteriorating state. He was remembering happy times in an earlier age, seeing his parents and a cavalcade of other relatives and friends who had passed years before.

Hospice Care at home was called for in early June, along with a schedule of round the clock vigil shifts spent by us his immediate family members. My mother, his ex-wife, also unselfishly participated in this regimen. I recall many things from that time period, but two things I will share here. My dad asked one of the Hospice workers, a young lady, when her due date would be. I was somewhat embarrassed because I couldn't even tell if she as pregnant or not. She seemed quite surprised, yet flattered by the question, and explained that she and her husband had just found out a few weeks before and were in the process of telling family and friends. She questioned my father how he knew she was pregnant? He replied that he could tell by the special glow she gave off. She was touched, and he wished her the best of luck and happiness as a mother into the future.

On June 8th I was covering an overnight shift, actually sleeping in a chair by my father's bedside. I was abruptly awoken around 3am in the morning by my dad talking to someone. He was actually still asleep and appeared to be talking to his mother about his day at school. I was floored by this and listened intently for the short time it lasted. About an hour later, he remained asleep but asked the question: "Chris, what do you want for Christmas this year?" I told him that he could get me whatever he wanted. He retorted back a list of possible items, all toys from my childhood. Words can't put into words how amazing this experience was.

I vividly remember Friday, June 11th as the day Hospice staff moved Dad from his upstairs bedroom to the living room on the main level. Ronald Reagan’s State funeral was on the television in the other room. My father, a devoted Reagan supporter and fan, shared sympathy, but had no desire to watch. Fifty-five hours later, my father would breathe his last breath during the early morning hours of Flag Day, Monday, June 14, 2004.

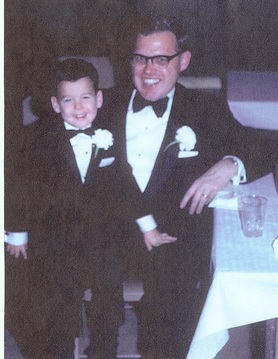

Chris with his dad at a wedding in 1969

Chris with his dad at a wedding in 1969

Edwin A. Haugh’s final day had been spent in the privacy of his own home—a house he helped design, and supervise in construction. My brothers and I had made sure the temporary hospital bed was set up within the footprint of Dad’s beloved model train set. We configured the track to go around, and under, him. He was failing fast and heavily sedated, but he had awareness of that train and all of us. It was an incredibly sad time, but one filled with the rye sense of humor he had helped instill in my brothers and I. In addition, the air carried the laughter of two grandsons playing with his train set and the occasional bark of his Bassett Hound Trixie.

The most special part of this critical life moment for me was having the opportunity to properly say goodbye and thank you to my life’s idol and mentor. Late that Sunday afternoon, I found myself leaning over and talking to him. Dad couldn’t really speak but his hazel eyes were open, attentive and he could slightly nod his head. I told him that if anything else, he was lucky for one reason—soon he’d find all the answers to our family history quests and questions. He’d get them straight from the sources themselves up there in heaven, seeing once again his mother, father, grandparents, Uncle Bobby Warfel and countless ancestors he had only heard/read about in stories and research. I told him that I’d be working on these riddles for the rest of my life, knowing many would go unanswered. This lightened the mood in the room, giving all adults an opportunity to smile.

I then announced that I should let someone else take my spot beside him. I was answered with a muffled “No!” by the patient himself. So I remained in my position. At that moment, the two of us proceeded to engage in a 10-minute gaze of each other. The room suddenly fell silent and this lasted for the entire duration. It was like a staring contest, I couldn’t look away and seldom blinked—it was as if we were both remembering all our past moments in life together. Looking back, it was me who was the lucky one, as I had a clearer window into his world, all thanks to my proactivity in having him share his life stories with me.

The most special part of this critical life moment for me was having the opportunity to properly say goodbye and thank you to my life’s idol and mentor. Late that Sunday afternoon, I found myself leaning over and talking to him. Dad couldn’t really speak but his hazel eyes were open, attentive and he could slightly nod his head. I told him that if anything else, he was lucky for one reason—soon he’d find all the answers to our family history quests and questions. He’d get them straight from the sources themselves up there in heaven, seeing once again his mother, father, grandparents, Uncle Bobby Warfel and countless ancestors he had only heard/read about in stories and research. I told him that I’d be working on these riddles for the rest of my life, knowing many would go unanswered. This lightened the mood in the room, giving all adults an opportunity to smile.

I then announced that I should let someone else take my spot beside him. I was answered with a muffled “No!” by the patient himself. So I remained in my position. At that moment, the two of us proceeded to engage in a 10-minute gaze of each other. The room suddenly fell silent and this lasted for the entire duration. It was like a staring contest, I couldn’t look away and seldom blinked—it was as if we were both remembering all our past moments in life together. Looking back, it was me who was the lucky one, as I had a clearer window into his world, all thanks to my proactivity in having him share his life stories with me.

Dad soon drifted off to sleep, marking his final period of alert consciousness. He officially left us seven hours later at 2am. That eye-locked gaze was one of the most magical and memorable moments of my life, another gift. We soon had his body brought back to a special place—laid to rest in Delaware City. The cemetery is in close proximity to his grandparents farm and his two childhood homes, the latter still owned by his brother Bobby, named for the boys’ fallen uncle. Dad’s grave is only a few short yards from those of his father, mother, Aunt Betty and Warfel grandparents.

Chris and Edwin S. "Eddie" Haugh,

July 21, 2006

Chris and Edwin S. "Eddie" Haugh,

July 21, 2006

Those last few weeks, combined with months of research and reminiscing, had prepared both of us (Dad and myself) for the inevitable event that lay ahead. He was so supportive and proud of my interest in all aspects of history. This was certainly something he had nurtured from the beginning. Dad said I had eased his pain and mind with all my hard work, happy that he had not only passed on the love of history, but said I gave him the chance to pass on his own personal story to someone who held it equally precious.

My father provided me with an incredible documented legacy. This was affirmed again two years later, in July 2006, when I gazed into the crystal blue eyes of my newborn son for the first time. I immediately flashed back to that magical experience at my dad’s bedside in mid-June, 2014. As his life had passed, I was experiencing the beginning of a new one and carved from my father’s legacy. I was now a father—and appropriately gave my son the name Edwin.

Proudly powered by Weebly