HSP HISTORY Blog |

Interesting Frederick, Maryland tidbits and musings .

|

|

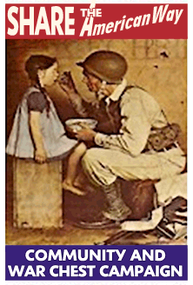

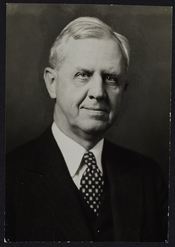

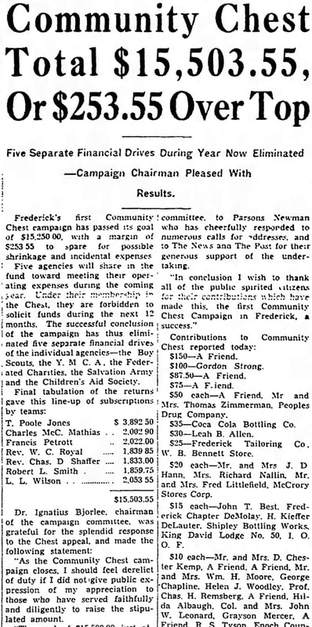

1938-1958 A fortunate occurrence in local history occurred in the year 1938. It was the beginning of “united giving” in Frederick with the formation of the Community Chest. This fund-raising organization was created to collect money from local businesses and workers to be distributed toward important charity and philanthropic projects in the community. The initial impetus of the program came as a remedy to assist in funding the operating budgets and capital needs of several partner agencies.  Joseph D. Baker "Frederick's First Citizen" Joseph D. Baker "Frederick's First Citizen" “Timing is everything” as they say. Ironically, or by divine design, this was the same year that Frederick lost its great and iconic benefactor—Joseph D. Baker. Given the moniker of “Frederick’s First Citizen,” Mr. Baker died October 6th, 1938 at the age of 84. His legacy includes generous donations that would create the Buckingham School for Boys; the Record Street Home for the Aged; the Baker Annex at Frederick City Hospital for the county’s African-American population; the Frederick YMCA; a new home for Calvary Methodist Church and a spacious municipal park that bears Mr. Baker’s name. Upon his death, friend James H. Gambrill, Jr. remarked, “The influence of his life will remain as a continued benediction upon the city of Frederick.”

Also stepping up in times of need were local businesses such as the Frederick News, Ox-Fibre Brush Company and the Union Knitting Mills. Nothing illustrates this latter point better than the thrilling events of July 1864 during the American Civil War when Frederick’s leading banks provided necessary funds to pay the infamous $200,000 ransom levied by Confederate General Jubal A. Early. The city was spared.  The timing of Frederick’s Community Chest creation was impeccable. Over the next several decades, this organization would incur multiple name changes and eventually come known as United Way of Frederick County. All the while, the citizenry’s passionate spirit of giving has remained the same for 80 years. Earlier Frederick residents and business persons have passed the torch to later generations, as well as newcomers to the area, dedicated to the cause of assisting the unfortunate and impoverished in our community. For eight decades, a variety of non-profit groups and agencies have received invaluable support from Frederick’s “united giving” organization thanks to both big and small business entities, local institutions and private citizens. Donations have come in the form of manpower hours, cash pledges, matching grants and supplies totaling in the tens of millions. Today, United Way of Frederick County brings the community together to provide resources that aid people in need, or at risk, in order to help solve problems. This is the same intention that started the organization here in 1938.  GENESIS (1938-1958) Although we look to 1938 as the year of founding, United Way of Frederick County was first conceptualized nearly a century ago, thanks to the mobilization of the country’s population and economy during World War I. The support efforts on the home front required soldiers, food, ammunition and money—key necessities to win the international conflict. Frederick County residents certainly did their part, and Allied efforts secured victory in November, 1918. All the while, valuable lessons regarding the importance of preparedness and teamwork were gleaned from this terrible chapter in our country’s history. As soldiers returned home from Europe and elsewhere, the United States found itself as one of the world’s top military and economic powers. National leaders saw the need for better organization and improved amenities at home. Soon began infrastructure changes to the armed forces, roadways and transportation systems, and government agencies. It was a time of social and political reform, and economic prosperity that would usher in “the Roaring Twenties.” At the local level, community leaders, residents and veterans alike could reflect upon the power of their collective actions in the recent war effort. Many began to feel a renewed vigor, and entertained the notion of waging war on a new foe—the ills and social problems here at home. These could be addressed by a “united” effort of care and fund-raising among neighbors, in an attempt to further improve Frederick County.

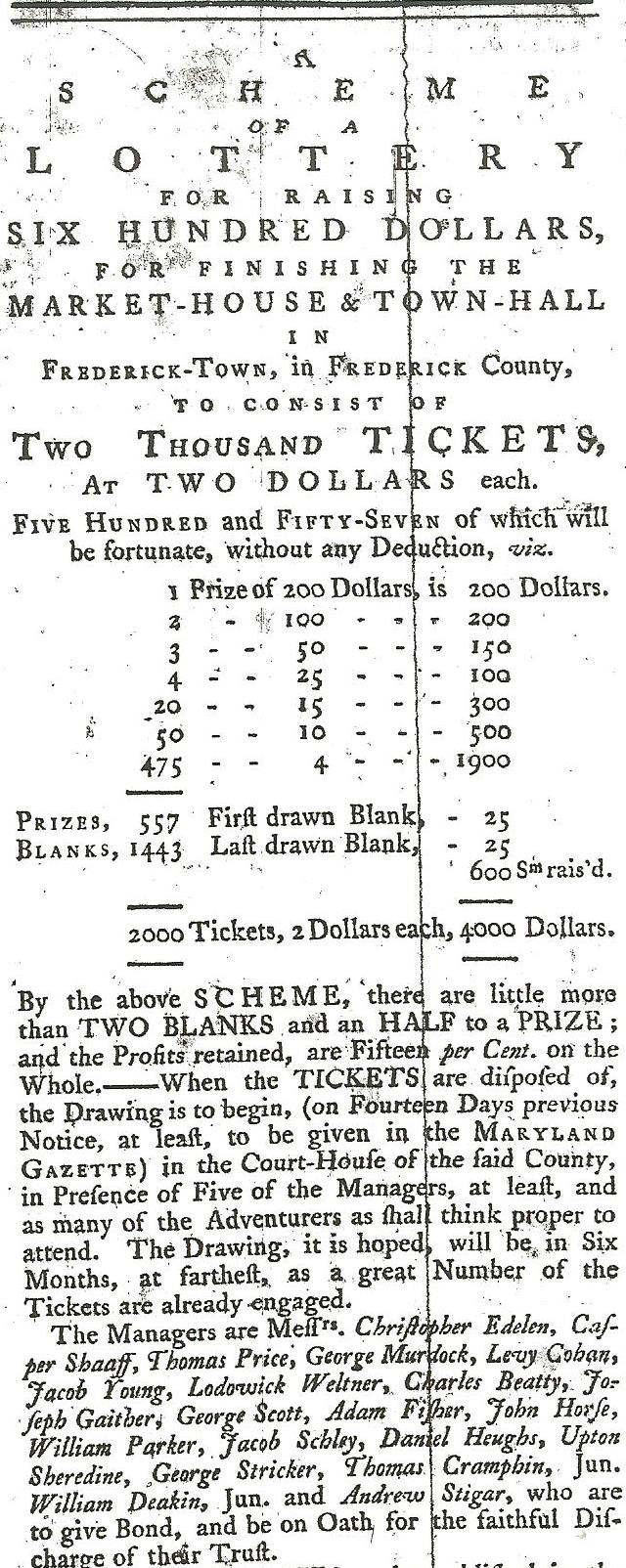

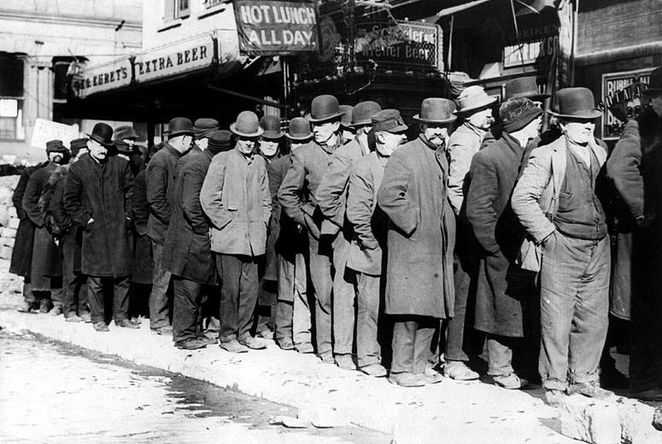

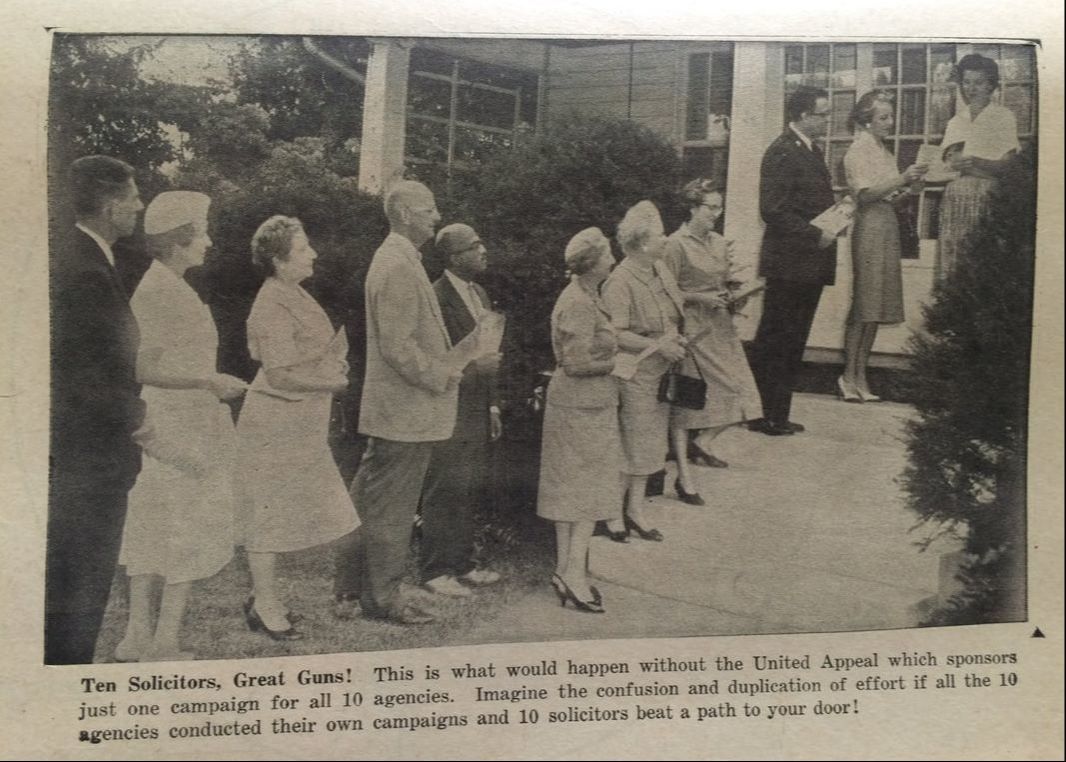

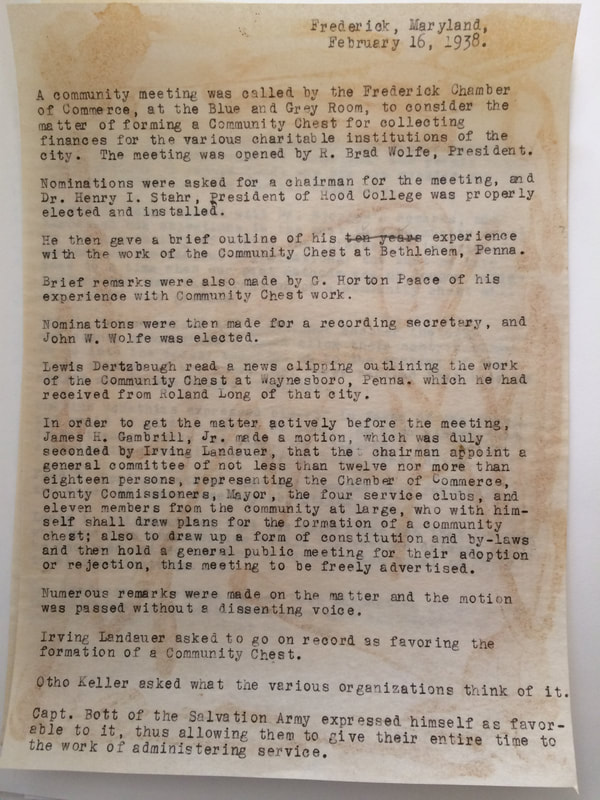

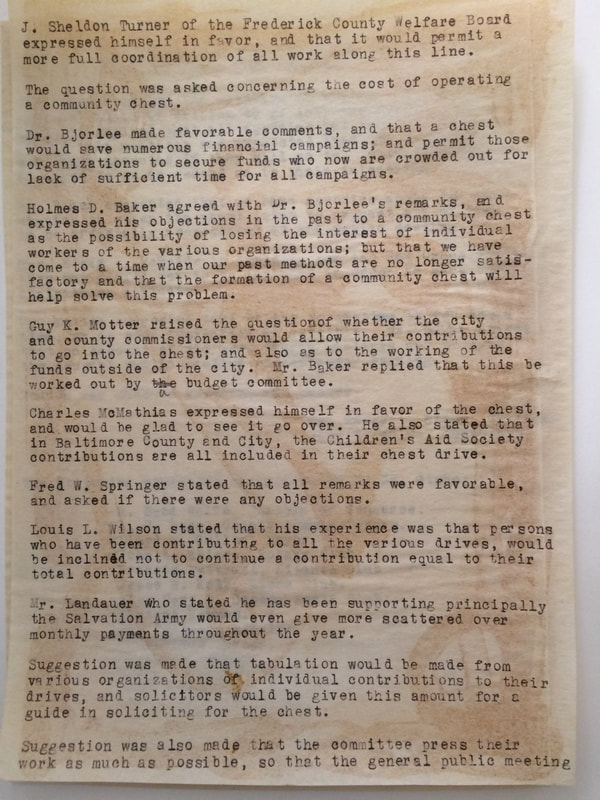

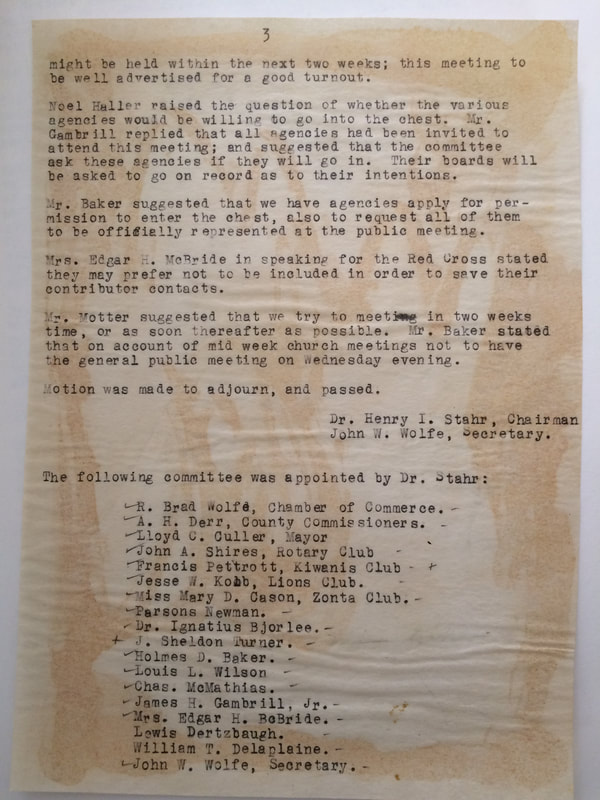

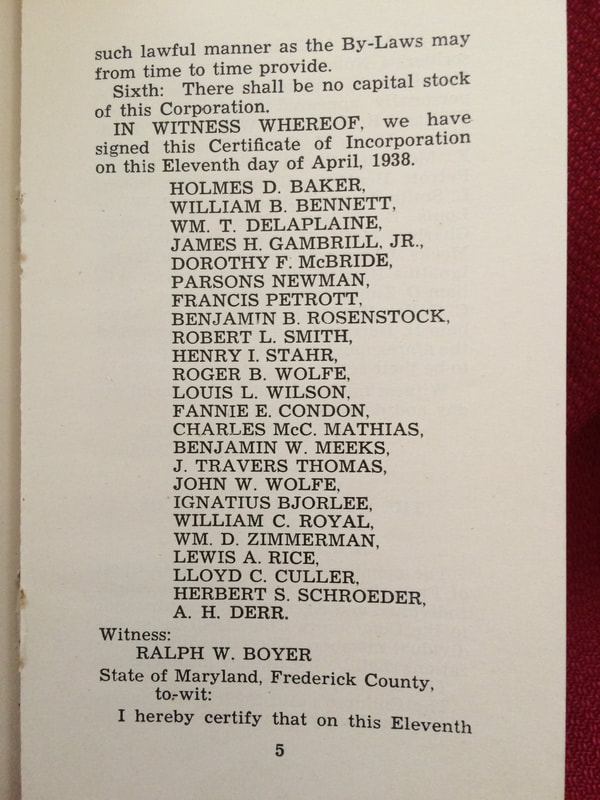

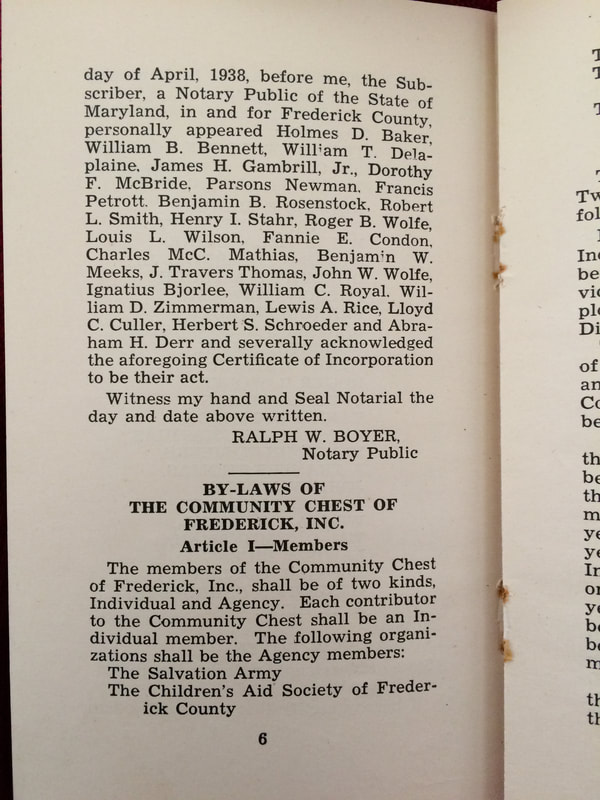

The Community Chest organization dates back to Cleveland, Ohio and the year 1913. It had the purpose of conducting organized, fundraising campaigns with local businesses and employees—the proceeds distributed to important local projects. The drive to establish a group like this in Frederick would take several years as not everyone favored the idea. Consternation and cynicism were expressed by more than a few of Frederick’s established fundraising enclaves such as fraternal organizations, church councils and civic groups. Some felt that a new “charitable union” would undo individual successes, and feared fund management by someone other than themselves. The matter of a united fundraising entity would be tabled until 1932, at which time the Frederick Lions Club re-introduced the idea for a Community Chest program. John W. Wolfe, chairman of the Lions’ Welfare Committee, was named to head a group to study the "Community Chest" concept and report his findings to the club. A year later, the local chapter of the Salvation Army would endorse a community chest for Frederick at its June meeting in 1933. Again, no formal movement would be taken. Florence Garner, leading member of the Federated Charities organization was among the Salvation Army’s advisory board in support of the plan. Founded in 1911, Federated Charities was headquartered at 22 S. Market Street in the old home bequeathed by Margaret Janet Williams, daughter of a former Frederick banker, John H. Williams. This umbrella group oversaw a Free Kindergarten for the community and the operation of the Charity Organization Society which provided assistance to families that could not be helped by other agencies. Services included a Prenatal Care Clinic, visiting nurse and drug prescriptions and the distribution of medical equipment, food, heating oil and used clothing to families that qualified. Florence Garner was the General Secretary of Federated Charities and carried a great deal of clout in the community, especially in addressing medical and social needs. She had originally come to Frederick from Ohio in 1912 to fill the organization’s position as visiting nurse. Ms. Garner helped lay the initial groundwork for Federated Charities and rose to lead the organization, staying for 38 years until her retirement in 1950. Having Ms. Garner as an advocate (for a Frederick Community Chest) certainly spoke volumes.  Certificate of Organization Membership for the Frederick County Chamber of Commerce Certificate of Organization Membership for the Frederick County Chamber of Commerce Enter the Chamber The country was quite a bit different than it had been a decade earlier. Residents had seen the legendary stock market crash of 1929, launching the era known as the Great Depression. Its effects would be felt for over 12 years as many people lost money in the form of savings and inheritances. Others found themselves without jobs, with new ones hard to find. In 1930, more than 14,400 people lived in Frederick City, the county population was 54,440. There were plenty of businesses and employers in town, but Frederick sorely lacked jobs in large industry. Regardless, Frederick had an organized Board of Trade, originally chartered in 1912. The newly christened Frederick County Chamber of Commerce was the first chartered “Chamber” in the United States. In the 1920’s, the local Chamber adopted the slogan, "If Frederick is worth living in, it is worth working for!"  CCC workers constructing the Catoctin Recreational Demonstrational Area CCC workers constructing the Catoctin Recreational Demonstrational Area Meanwhile, President Franklin D. Roosevelt was moved to institute his “New Deal” plan (1933-1938) as a means to provide employment through federal programs such as the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) among others. If there was ever a time for much needed charity, this was it. A few years would pass until January 1938. The time to consolidate Frederick’s varied charity drives was long overdue. The Frederick County Chamber of Commerce announced a goal to secure a community chest for Frederick, once and for all. Chamber members and local businesses had oft been targeted to assist in leading, and making contributions to, local charity campaigns. Oftentimes this would make many individuals and businesses feel overwhelmed by multiple requests to participate in competing fund drives. Worse yet, they found it increasingly hard to say no.  The Community Chest offered a great solution for pooling resources and time, not to mention cross-marketing the many needs of the community to the populous. Plans were discussed for a single, annual drive to replace independent, money-raising campaigns. Competition would soon be eliminated as various charities would share proportionately under the Community Chest model. A community meeting was scheduled for mid-February to consider whether the time was right for a community chest for Frederick. This would be held at the Francis Scott Key Hotel in downtown Frederick on the night of Wednesday, February 16th, 1938. The following day, the Frederick News featured the headline "Community Chest Idea Gains Impetus." Thirty-three Frederick citizens and representatives of charitable causes apparently "threshed" out the question of whether it could be carried out. Hearty sentiment was shown, and without dissent, the group voted that a committee of 19 persons draw up plans for such a chest and submit them at a public meeting to be held for the purpose within three weeks. The actual minutes from this meeting are preserved within the archives of Heritage Frederick (formerly the Historical Society of Frederick). They appear below: On March 22nd, a public meeting to consider the draft of a constitution and by-laws for the proposed Community Chest would be held at the Francis Scott Key Hotel. Here the assigned committee had opportunity to show their work. Overwhelming support was demonstrated again, and another meeting was scheduled for March 25th, one in which a board of directors would be elected and officers named. The strength and ties of the Frederick County Chamber made the “united giving” model a reality on April 11th, 1938. This was the day that the Articles of Incorporation were officially signed by 24 individuals, and filed with the State of Maryland.

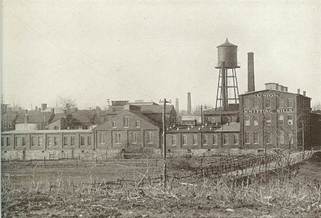

Delaplaine Food Drive of 1895 Delaplaine Food Drive of 1895 The organization’s Second Vice President was William T. Delaplaine (Jr.), son of the founder of the Frederick News. Delaplaine made sure that the idea of the community chest got plenty of traction in his family's newspaper. Interestingly, his father, William T. Delaplaine (Sr.), had died as a result of contracting pneumonia attributed to tireless efforts associated with a charitable food drive performed by the newspaper during the harsh winter of 1895. The Frederick Community Chest’s secretary was John W. Wolfe, the man charged by the Frederick Lions Club to study the community chest’s feasibility a few years earlier. The first treasurer was William D. Zimmerman (Cashier of Frederick County National Bank). Also holding spots on the Board were two sons of great philanthropists from the area’s past: Holmes D. Baker (son of “Frederick’s First Citizen” Joseph D. Baker) and James H. Gambrill, Jr. (son of James H. Gambrill, successful agriculturalist and miller). The latter operated the Mountain City Mill for decades, today known more commonly as the Delaplaine Center for the Arts. Gambrill Park was named for James, Jr. in honor of his tireless fight for public recreation facilities and nature conservation. Rounding out the first Board of Directors of the Frederick Community Chest were William B. Bennett (Bennett’s clothing store), Dorothy Filler McBride (President of the Maryland State Board of Examiners of Nurses) and Dr. Ignatius Bjorlee (President of the Maryland School for the Deaf from 1918-1955). Other leading citizens to lend their support and energies included Parsons Newman (fine antiques expert), Benjamin B. Rosenstock (canning company owner), Charles McCurdy Mathias, Sr. (lawyer/politician), Russell Ames Hendrickson (owner of a ladies clothing store) and William Bartgis Storm (Citizens Bank/president of the United Fire Company).

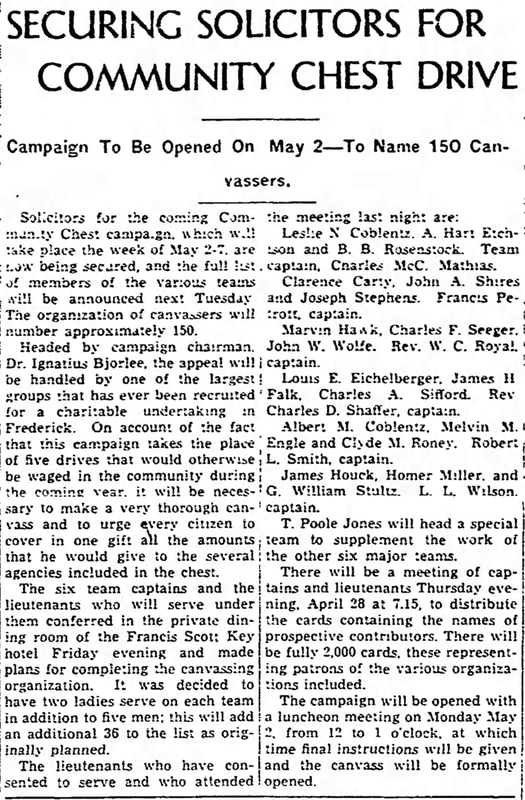

A volunteer paints in an adjustment to a Community Chest thermometer in Wisconsin A volunteer paints in an adjustment to a Community Chest thermometer in Wisconsin A “Federated” New Home By late June, 1938 the Community Chest would have a home base of operations. This would be the former domicile of Frederick banker John H. Williams. The house more recently had been inhabited by Federated Charities and was located at 22 S. Market Street. Greeting visitors was the aptly named iron, dog statue on the front portico—“Charity.” This four-legged icon had been on the site since the start of the Civil War. A second Frederick Community Chest drive would occur in May, 1939, and was headed by Robert L. Smith, District Manager for the Potomac Edison Power Company. The goal of the campaign was upped to $16,550. Results were displayed each day on a large novelty thermometer, located on the front of the Federated Charities building (22 S. Market Street). By the end of the drive period, funds were $2,500 under the goal. The family of Joseph D. Baker, Sr. stepped up with a $1,000 donation which sparked others to fulfill the goal amount. When it was all said and done, 2,359 different contributors had taken part in the campaign.

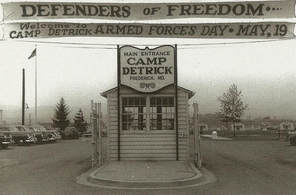

As the importance of these fundraising drives became better known to the residents of Frederick, success rates grew proportionately. The fifth Chest Drive appeal took place in May of 1942 and raised in excess of $2,000 over the desired goal. This was particularly encouraging due to a local and national climate characterized by participation in World War II causing the offshoot effects of apprehensive workers, a rising cost of living, war rationing and other unfavorable conditions. Against this backdrop, a new member was admitted to the Community Chest membership in late 1942 in the form of the Girls Scouts of Frederick. The next few years (1943-1945) would be especially trying. While war was raging on foreign soil, men and women here did their part to support the fighting troops. Many men traveled to Baltimore and Hagerstown to work in ship yards and aircraft plants. Local businesses such as the Union Knitting Mills, Ox Fibre Brush Company and the Everedy Company also played roles in the war effort.  Women packaged bandages in their homes for the Red Cross, an organization of paramount importance at this time—so much so, that the directors of the Community Chest decided to postpone their annual spring-based drive in deference to the Red Cross’ drive. When they proceeded the following fall, a partnership had been made with the National War Fund to conduct a joint campaign. This effort exceeded its quota as nearly $59,000 was garnered. The joint campaign would become the norm for the next two years. The respective campaign chairs in 1944 and 1945 were former veterans of World War I, not to mention the fact that they were from leading Frederick families: James H. Gambrill III, and R. Ames Hendrickson. After massive devastation of their own countries and loss of life, Italy surrendered in 1943, and Germany and Japan in 1945. On the other hand, the US emerged far richer and with fewer casualties comparatively. The Frederick community, and nation, learned once again the important lesson of teamwork, dedication and sacrifice in dire times of need. Post-War America Twelve million returning veterans were in need of work and in many cases could not find it. Inflation became a rather serious problem, averaging over 10% a year until 1950. Raw materials shortages dogged manufacturing industry. In addition, labor strikes rocked the nation, in some cases exacerbated by racial tensions due to African-Americans having taken jobs during the war and now being faced with irate returning veterans who demanded that they step aside. Munitions factories shut down and temporary workers returned home. Following the Republican takeover of Congress in the 1946 elections, President Harry Truman was compelled to reduce taxes and curb government interference in the economy. With this done, the stage was set for the economic boom that, with only a few minor hiccups, would last for the next 23 years. After the initial hurdles of the 1945-48 period were overcome, Americans found themselves flush with cash from wartime work due to a slowdown in buying for several years. The result was a mass consumer spending spree, with a huge demand for new homes, cars, and housewares. Increasing numbers of people enjoyed high wages, larger houses, better schools, more cars and home comforts like vacuum cleaners, washing machines—which were all made for labor-saving and to make housework easier.  Here in Frederick, many found employment at Frederick’s Camp Detrick, a US Army installation specializing in medical and biological warfare research. Others took employment located throughout the county and region as government jobs were becoming more plentiful. GI Bills assisted veterans in completing education and securing loans for such things as automobiles and houses. This became a contributing factor for an increasing population characterized as “the Baby Boom,” in turn, bringing a greater demand for improved educational facilities, medical amenities and of course, social services. As many families began migrating to the rapidly expanding suburbs, optimism was the hallmark of the new age—an age of grand expectations. The Roosevelt administration of the previous decade generated a set of political ideas—known to later generations as New Deal liberalism. This remained a source of inspiration for years to come. Community Chest campaigns over the next few years had cash collections that nearly doubled those before the war.

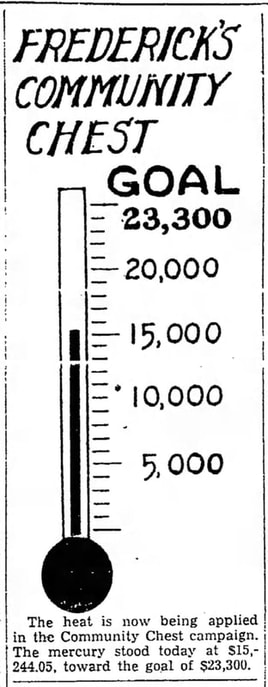

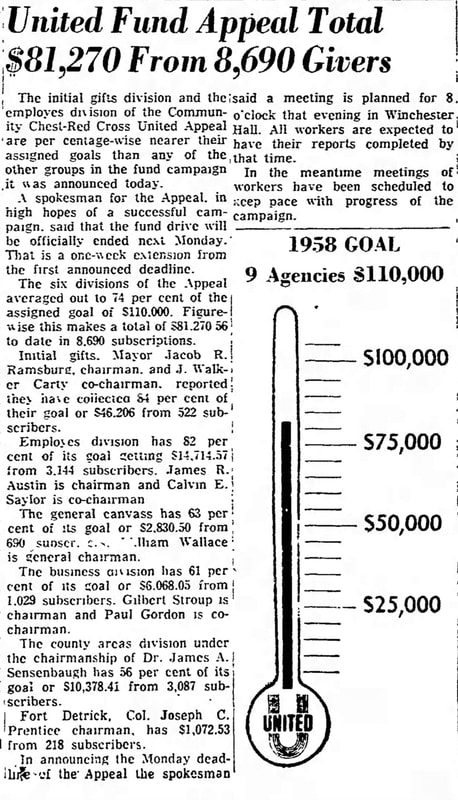

Before decade’s end, more successful drives were enjoyed and another non-profit member was accepted for membership. This was the Esther E. Grinage Kindergarten, the first such pre-school opportunity for African-American children in modern times in Frederick. Much of Frederick was still segregated at this time. This was exemplified here in Frederick with public schools, hospital entrances, parks, restaurants and movie theaters. The gesture of support by the Frederick Community Chest spoke volumes during a difficult time of racial inequality visibly present at the local, state and national level. The 1949 campaign drive was also noteworthy and historic in the fact that it marked the first time Frederick’s local Black population became involved in earnest with the organization that would one day become known as the United Way. As the Community Chest entered the decade of "the Fabulous Fifties," Harry Truman would be followed as president of the United States by the Republican war hero, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower. He was a moderate who did not attempt to reverse Franklin D. Roosevelt's "New Deal" programs such as regulation of business and support for labor unions. President Eisenhower actually expanded Social Security and built the interstate highway system. This was also a time of confrontation and fear as the capitalist United States and its allies politically opposed the Soviet Union and other communist countries—the Cold War had begun. Community Chest drives would continue throughout 1951-1959 with an annual average collection of $52,000. Each year now brought a new Frederick Community Chest president to the forefront. Names would include Glenn T. Swisher (Comptroller-Potomac Edison Co.), Paul McAuliffe (Manager-Francis Scott Key Hotel), Niemann Brunk (Owner-Frederick Produce Co.), Byron Winebrenner (Comptroller-Frederick Produce) and Charles S. V. Sanner (Insurance Agent).  As locals would first see the emergence of a singer named Elvis Presley and a re-designed Chevrolet automobile, the Community Chest’s Board of Directors under president (and local attorney)Parsons Newman decided to re-tool their own organization on a county-wide basis. They also instituted the “United Fund Campaign” for the entirety of Frederick County. Local Farmers &Mechanics Bank President Benjamin L. Shuff was appointed campaign chairman, and put together the first countywide campaign. Another historic element of this campaign was the first-ever use of a payroll deduction plan for employee donors. On September 25th, 1957, a well-attended dinner meeting of the Frederick County division of the Community Chest was held at the Francis Scott Key Hotel. Among those in the attendance were 50 area captains and election district chairpersons of the campaign from rural areas around the county. The keynote speaker was past Chest president, and campaign chair, Charles S. V. Sanner. He was a one-time special assistant to the Fort Detrick commandant, along with being a realtor and insurance agent. Sanner gave an overview of the Frederick Community Chest’s first 20 years in Frederick from formation to the recent countywide drive. He also spoke about the member agencies that the campaign helps each year. “Respect for the privacy of the individual recipients of our aids,” Sanner said, “has prevented many of our county services from being generally known to the public. These are not old-fashioned charities but vital public services and character building organizations.”

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorChris Haugh Archives

February 2024

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed