HSP HISTORY Blog |

Interesting Frederick, Maryland tidbits and musings .

|

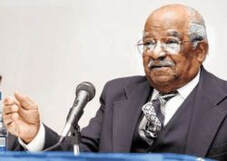

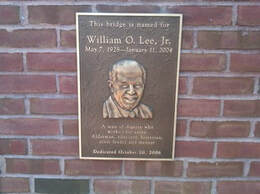

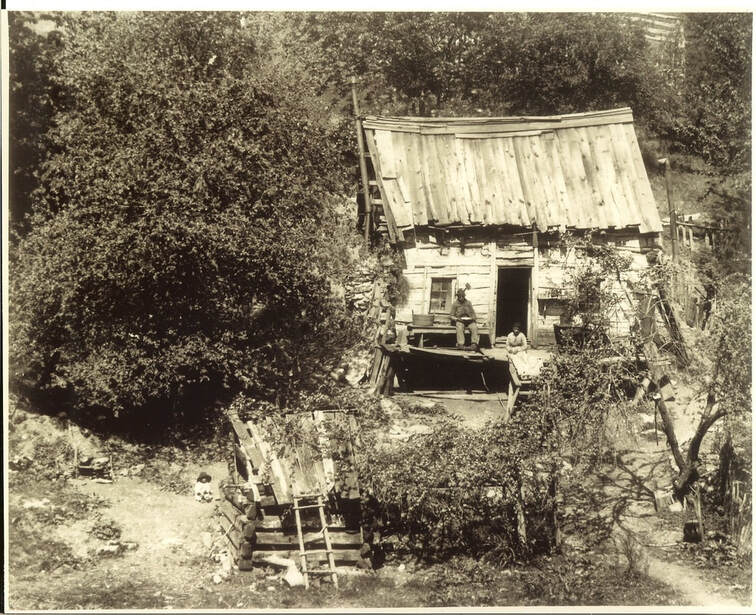

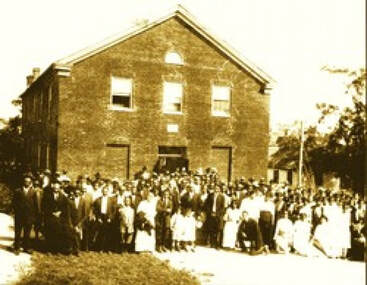

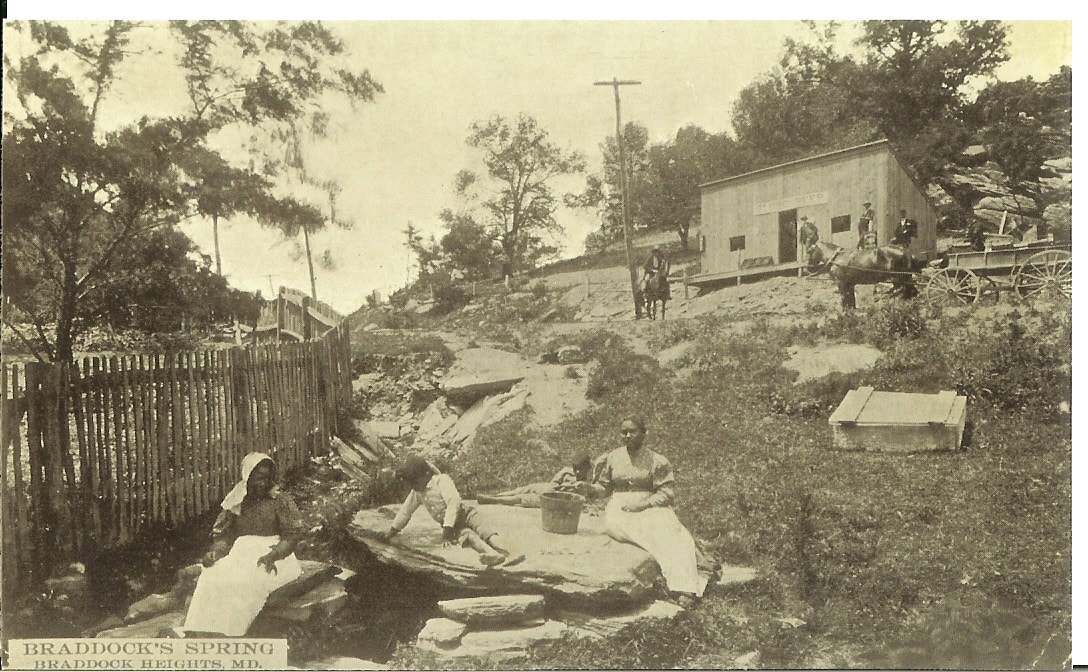

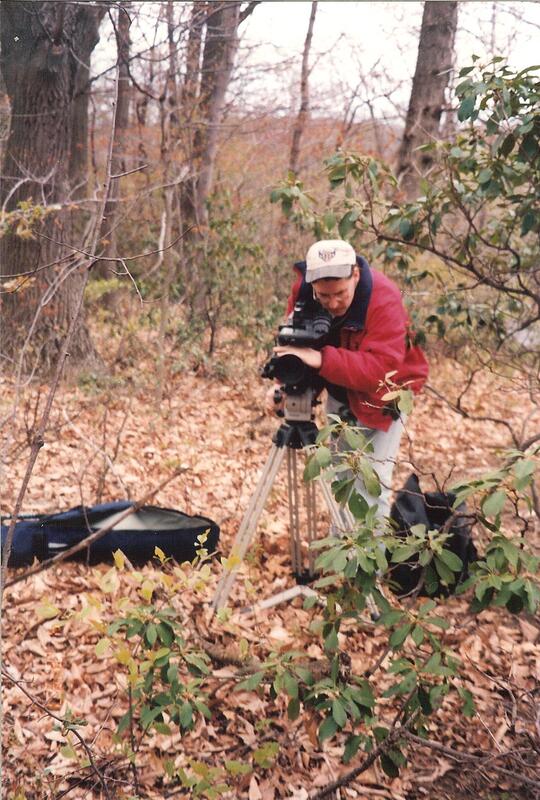

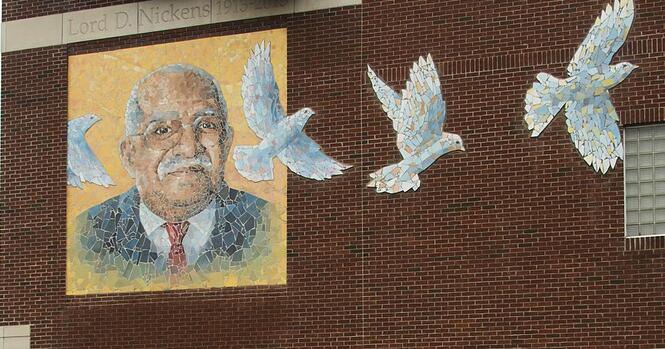

I am enjoying a period of great reminiscing of late. It was 30 years ago (February 1994) that I was inspired to produce a video-documentary project focusing on the Black history of Frederick County, Maryland. I wouldn't start production until two years later, and two years past that (March 1998), I surprisingly found myself on a stage in San Diego, California accepting an award called the Beacon Award of Excellence, the highest honor for communications and public affairs in the Cable Television industry. It was quite a thrill, but more so, a humbling experience as this award belongs to my many "teachers" for this endeavor, along with a host of people I only knew as gravestones, sprinkled throughout the county —their spirits were certainly guiding me. The five-hour documentary was given the title Up From the Meadows, a play on the opening line from John Greenleaf Whittier’s famed poem about hometown Civil War heroine Barbara Fritchie. Throughout the production process, I was able to live in the moment, as I knew that creating this long-form television program would not only educate and humble me (a white male born at the tail-end the Civil Rights Movement period) but would certainly shape my thinking about past events, places and persons. I went into the project with the basic Black history knowledge I had carried since my childhood and early school days. There were the obvious stories of Martin Luther King, Rosa Parks, George Washington Carver and Jackie Robinson. I also could make connections to my home state through legendary native Marylanders: Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, Benjamin Banneker and Thurgood Marshall. When I was 10 years old, my parents encouraged me to watch the “Roots” television miniseries, which premiered in 1977. Like countless other Americans, black or white, I became inspired toward a lifetime search to know my own ancestors. However, the greater takeaway was getting my first glimpse of a dramatization of the African slave trade and the institution from Colonial America up through the American Civil War, and continued prejudice and segregation that would permeate society in the century to follow. It made quite an impression. From time to time, I thought about delving into a Black history of Frederick, and was inadvertently pushed over the threshold by the late Dr. Len Latkovski (1943-2015), beloved former professor of history and political science for Hood College. I had utilized Len as an on-screen commentator for an earlier Frederick City history documentary entitled Frederick Town which I began producing in 1993. The seasoned professor, originally from Latvia, amazed me with population statistics and anecdotes relating to Frederick County’s slave and free black populations. He also encouraged me to look at slavery through the lens of different religions and their views on slavery (particularly Catholicism, Methodism and the Society of Friends). Len made me realize that Frederick County’s past made for a unique case study of the African-American experience. Where else could you find such a great number of free and enslaved black people living in the same environs—a place bordered by the Mason-Dixon Line to our north, and the Potomac and Virginia, capital of the Confederacy to our south? And all this set in motion and dictated by the original white European cultural-settlement patterns of Frederick County. I would zero in on this “border county within a border state” notion as a central tenet for my proposed “Black history” documentary. My experiences with Up From the Meadows have been readily coming to mind over the past few month. I’ve been preparing lectures and readying materials for an upcoming, multi-week class on the subject that I am slated to teach (in March and April) under my History Shark Productions moniker. Students will view portions of the documentary, interspersed with an illustrative PowerPoint presentation. I plan on explaining the production process, and discussing pertinent points of subject matter. Simply put, the four-part course will be “chock-full” of historic events, places and people from Frederick County’s past that once hovered “below the proverbial radar.” And for a story this rich and important, I can’t say I will be teaching alone. I will have a host of on-screen instructors helping me out, just as they did back in March 1997 with the program’s premiere on local cable television.  Dr. Blanche Bourne Tyree (1917-2019) Dr. Blanche Bourne Tyree (1917-2019) One of these “teachers” was Blanche Bourne Tyree, who holds the distinction of being the first woman from Frederick County to have earned a medical degree. She had a successful career as a pediatrician and a public health administrator for over 40 years. In retirement, she built an impressive resume of civic involvement, including a three-year stint as co-host of Young at Heart: Frederick County Seniors Magazine, a program I proudly oversaw as executive producer while at GS Communications' Cable 10. Medicine would certainly define Blanche Bourne Tyree’s immediate family’s life. Her father was a man named Dr. Ulysses Grant Bourne, Frederick’s first Black physician. Dr. U.G. Bourne hailed from Calvert County, and came to segregated Frederick in 1903, after completing his education in North Carolina at Leonard Medical College. Despite being allowed to practice at Frederick Memorial Hospital, Dr. Bourne went on to open a 15-bed hospital for Blacks on West All Saints Street in 1919. This would be the first county hospital to accept patients of color. Dr. Bourne was a magnificent civic leader as well, whose many accomplishments include the founding the Maryland Negro Medical Society and co-founding Frederick’s NAACP chapter. His name now adorns the Frederick County Government building formerly known as the Montevue Assisted Living Facility (located on Montevue Lane). His other two children experienced success in the healthcare field as well. Dr. Ulysses Grant Bourne Jr. became the first Black doctor to have privileges at Frederick Memorial Hospital, while daughter Gladys (Bourne) Thornton became a nurse. As snow and freezing rain fell outside, I fondly recall visiting Blanche at a local nursing home back in February, 2016. The 98 year-old had been plagued by recent setbacks which precipitated this stay away from her Crestwood Village home. I thought about how surreal things must have felt for a veteran physician and caretaker, now firmly in the role of patient. As I sat in awe of my beautiful friend, discussion on that morning included our past documentary and the day of our interview taping, one in which we were forced to “shoo” her late husband Chris (Tyree) out of the room we were using because he was interjecting too many comments from the “peanut gallery.”  Lord D. Nickens Lord D. Nickens We also recalled one of the true highlights of my professional career, something that began as a simple invitation Blanche had given me. This was in the early spring of 1998, and featured a road trip to find Blanche’s father’s original homestead and farm in lower Calvert County. I did the driving and along the way, we picked up Blanche’s cousin who would help guide us to the rural vicinity of Island Creek (near Broomes Island). This is where Blanche’s grandfather, Lewis Bourne, and wife Emily raised their ten children in a small rural Black settlement in the decades immediately following the Civil War. The old, family house had been boarded up for several years, slowly decaying into the surrounding landscape. I did, however, feel the importance of place here— having produced two generations of Bournes that would certainly shape Frederick into the great place we know today. With that 2016 visit, I again had the opportunity to thank Blanche for her assistance and friendship over the years, but especially with this project. She was my lone, surviving, on-camera commentator from the program which originally boasted 12 Frederick residents. It was moments such as the trip to Calvert County that helped give me a better understanding of Black history and legacy in Maryland, and of my home county in particular. As a white male, I will never be able to fully understand, but with this priceless tutelage, I was able to position myself as a conduit, relaying experiences from residents like Blanche who truly “lived” the documentary. Dr. U.G. Bourne was the father of one of my interview subjects, and mentor to another. Lord Dunmore Nickens (1913-2013) was truly influenced by Blanche’s dad, propelling him to take the lead in Civil Rights activism for the better part of his 99 years. Mr. Nickens taught me a great deal as well, and shared a myriad of personal experiences, “fighting the good fight,” on tape with me. He passed away more than a decade ago, but not before being honored with having a street in Frederick named after him. In 2014, a mosaic memorial mural depicting Mr. Nickens was unveiled on the side of a downtown building located at the corner of North Market and Lord Nickens streets.  Plaque honoring William O. Lee (1928-2004) adjacent Frederick's "Unity Bridge" in Carroll Creek Park Plaque honoring William O. Lee (1928-2004) adjacent Frederick's "Unity Bridge" in Carroll Creek Park Another Up From the Meadows alum was memorialized with a decorative suspension bridge crossing Carroll Creek. This waterway was once considered the dividing line between Frederick's white and black residents. William O. Lee (1929-2004) is best remembered as a longtime educator, municipal politician and community activist. This “gentle man” in the highest regard, can be credited as being among the first people to chronicle and promote Frederick City’s black heritage, highlighted by his childhood home of the All Saints neighborhood as the central hub for black life for well over a century. Mr. Lee walked me all over town, working hard to make sure I had a firm understanding of Frederick’s foremost endeavors in education, business, charity and social life in the segregated black community, and how barriers were finally chipped away in an effort to unite two Frederick’s into one—figuratively “bridging the town creek.”  Kathleen Snowden (1933-2008) Kathleen Snowden (1933-2008) What Bill Lee taught me about the city, Kathleen Snowden of New Market taught me on the county level. The self-proclaimed “outspoken” New Market resident shared her knowledge, based on years of intensive black history research. Ms. Snowden accompanied me as travel companion on several field trips. We searched for the remaining traces of former “Black sections” of leading towns (ie: Middletown, Brunswick, Libertytown) and explored “post-emancipation hamlets,” places like Sunnyside, Bartonsville, Della, Hope Hill and Coatesville. In addition, we experienced Black churches together, looked for old "colored" schoolhouses and walked countless Black burial grounds, seeing names in stone of former slaves and descendants of once-enslaved peoples, not to mention those of soldiers and prominent early free Blacks who lead their neighbors in the long fight towards equality.  Marie Erickson (1932-2011) Marie Erickson (1932-2011) Other teachers for me included 100 year-old Ardella Young of Pleasant View, Maude Morrison, Luther Holland, Arnold Delauter, Bessie Brown, Edith Jackson, Henry Brown and a lone, yet powerful white voice—Marie Anne Erickson. Marie taught me to embrace the fact that I was incapable of appreciating or fully understanding what my other subjects and the Black population (past or present) had experienced over their lifetimes. I was white, and male to boot, the long dominant power combination in our country since its inception. I had not experienced struggle of any kind, however I continue to feel no shame for events of the past, especially going back several generations. Marie Erickson was born and raised in Illinois, the daughter of Swedish immigrants who came to the US in 1923. She would pass in 2012, but not after four decades of assisting local Frederick Blacks in researching their roots, and gaining family connections. Marie was not only a friend to so many people of color, but became accepted as an “honorary” family member in many instances. All the while, she remained 100% genuine, not simply showboating for self-gain. Marie cared about equality and often looked for “teachable moments,” objects and opportunities in which to share illustrative “Black” stories and experiences with white and black readers alike. These appeared through her countless articles and letters to the editor in Frederick newspapers and magazines. A year after her death, Marie's daughter asked me to write the forward for a book to include many of her articles. This was published in late 2012 and is entitled, Frederick County Chronicles: The Crossroads of Maryland. As I said earlier, using Frederick County and its past for context, serves an amazing canvas to tell this story and introduce individuals such as William Ware, Elijah Lett, Professor James Neale, Decatur Dorsey, John W. Bruner and places like Oldfields, Centerville and Halltown. Current residents such as Joy Hall Onley and members of Frederick County's AARCH group (African American Resources Culture and History) continue their amazing work of "piecing together" and preserving this rich legacy. I might add that legendary resident, and founding AARCH member, Rose Chaney helped gather another group of amazing Black history storytellers for The Tale of the Lion, a documentary produced in 2018. Meanwhile, I’m happy to report that Black History Month will be extended through March and April this year for those individuals who take my upcoming “Up From the Meadows: the Class” course. While I market the fact that its my class, I think you can see that its only semantics. I will have plenty of help from former friends and mentors— true legends who helped research, preserve and make Frederick County's history, a mix of all colors when you really think of it. To learn more about the upcoming course (Tuesday evenings starting on March 12th-April 2nd), including registration instructions, click the button below:

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorChris Haugh Archives

February 2024

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed