HSP HISTORY Blog |

Interesting Frederick, Maryland tidbits and musings .

|

|

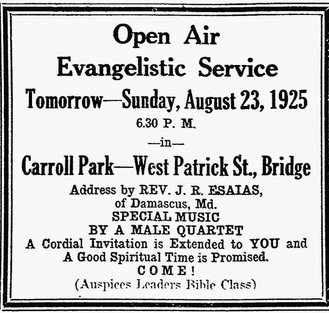

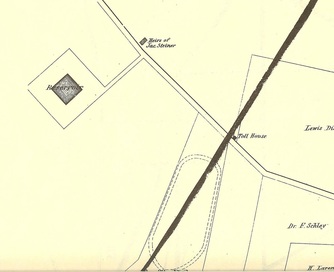

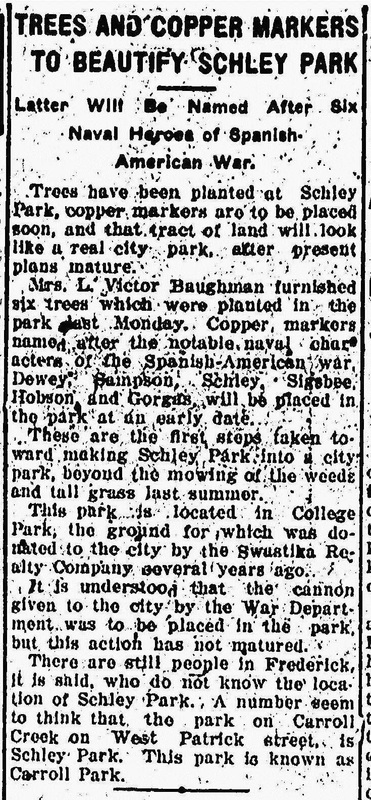

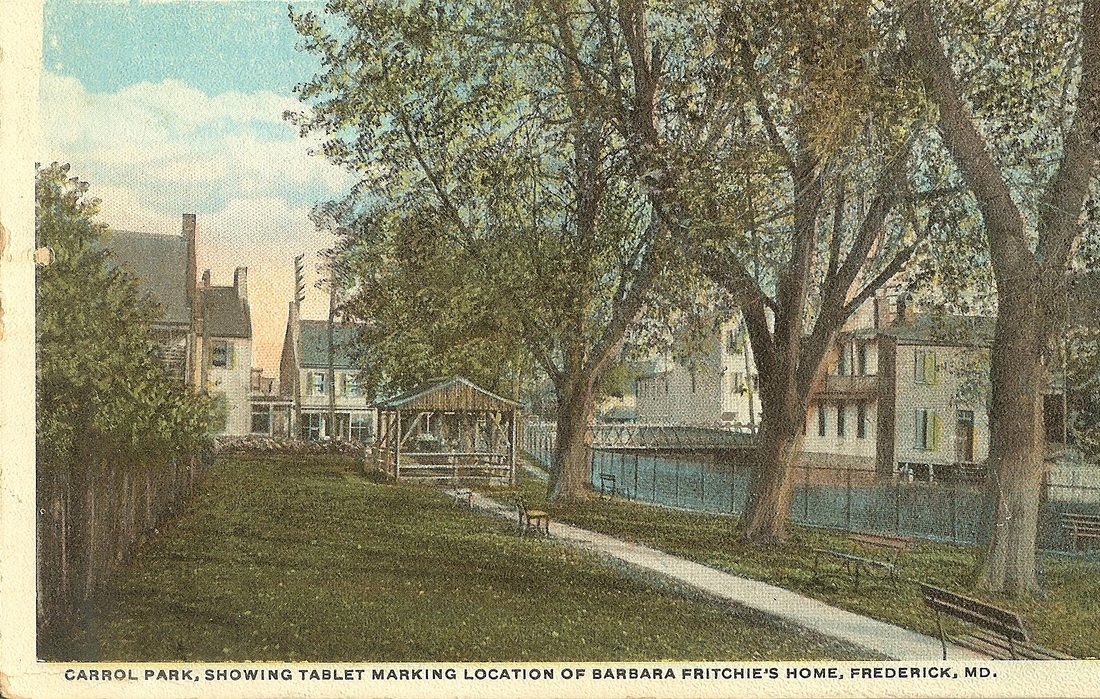

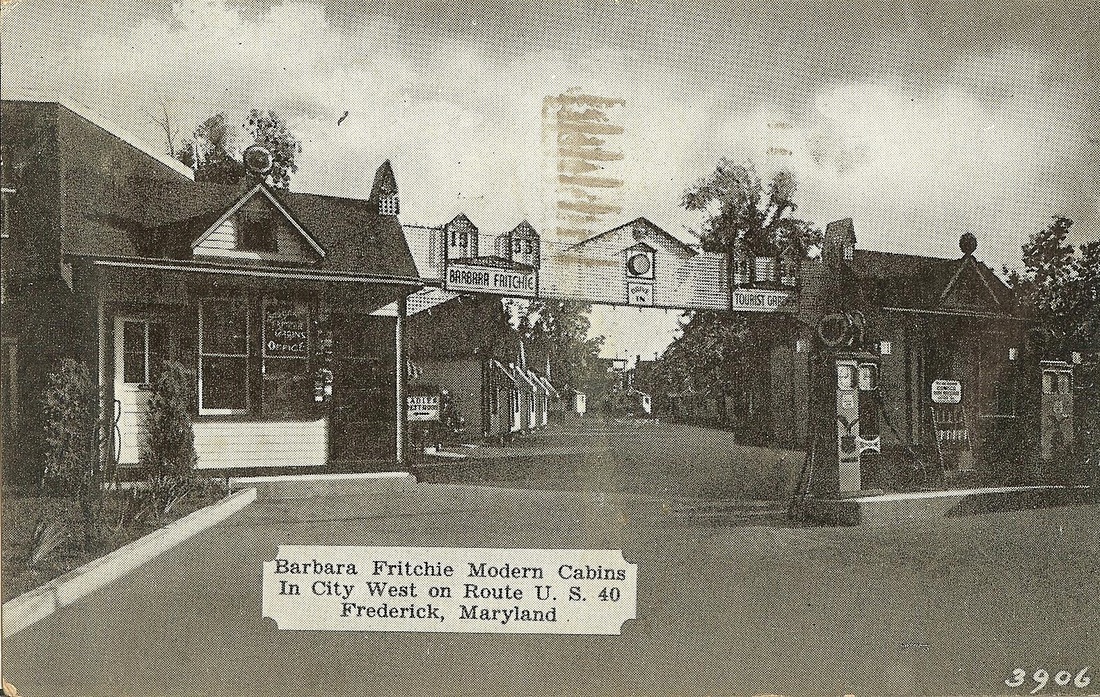

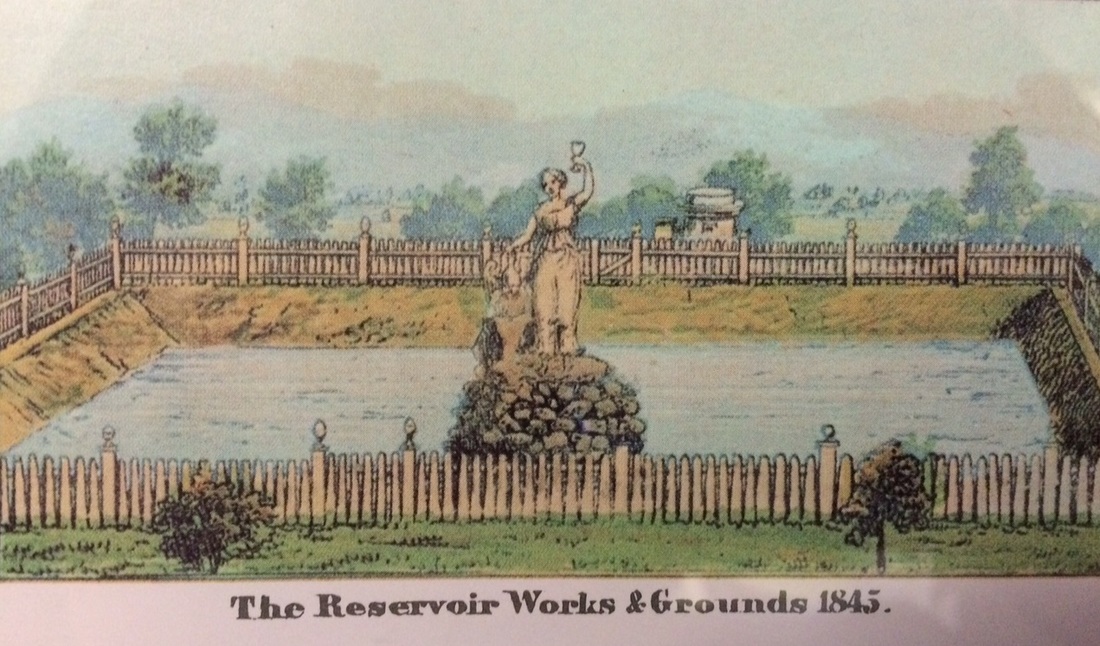

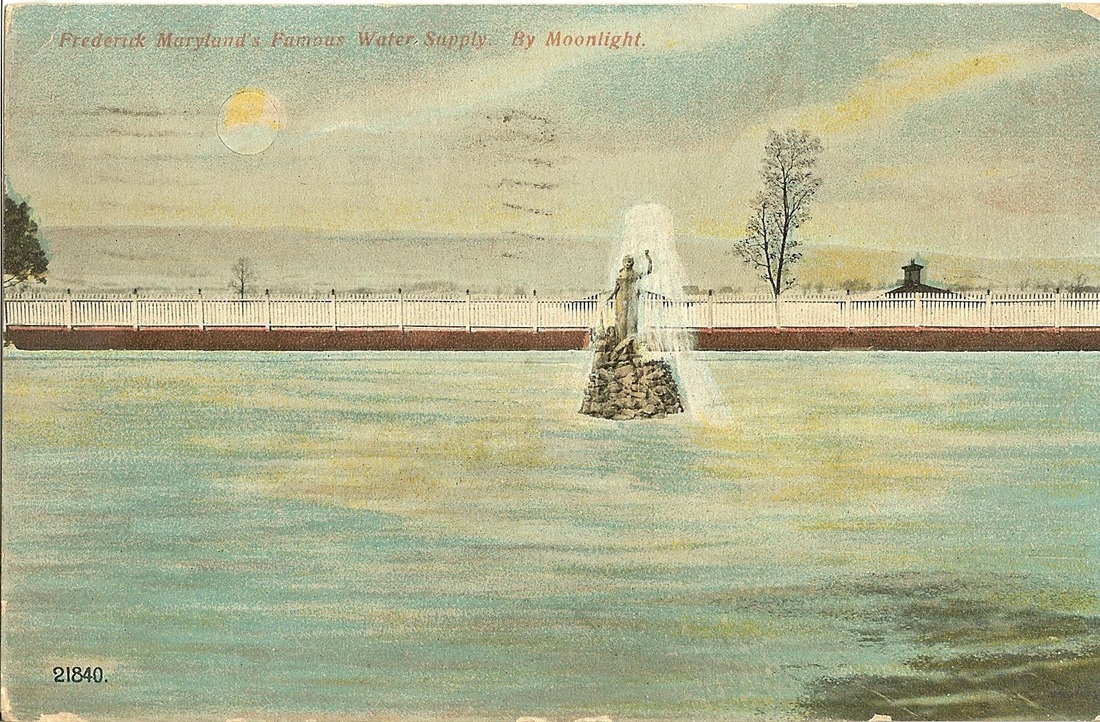

Last week’s blog centered on the Culler Lake renovations, and how the water feature within Baker Park came into being. This week, I want to review some earlier Frederick parks, with emphasis on those located in the western and northwestern reaches of Frederick City. I also want to call out a “predecessor” and inspiration for Culler Lake, just a few short blocks to the north. Schley Park This oft overlooked gem was established in 1913 as part of the College Park residential development, originally built by the Swastika Realty Company. The area encompassed rolling farmland west of Rockwell Terrace, south of the newly opened Hood College. The small oasis featured a contest to pick its final name. One of two choices included Scott Key Park, of course named for Frederick’s favorite son, Francis Scott Key (he of Star-Spangled Banner fame). The other choice was Schley Park, a nod to another Frederick native Winfield Scott Schley, naval hero of the Battle of Santiago in the Spanish American War which had occurred in 1898. I’m guessing at the time, it was safe to say that the park would not get off “Scott” free (as in Scot free). The latter choice won at the ballot box, and it’s been Schley Park for more than a century. After a positive start, the park apparently became neglected. it would enjoy a Renaissance in 1920.  George E. Burnap (ca. 1914) George E. Burnap (ca. 1914) The park, and surrounding layout for housing development and street design was created by a renowned landscape architect George Elberton Burnap (1885-1938). The Cultural Landscape Foundation offers the following biography on Mr. Burnap: Born in Hopkinton, Massachusetts, Burnap studied architecture and landscape architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Cornell, and, later, at the University of Paris. He served as landscape architect for the Office of Public Buildings and Grounds in Washington, D.C. and was involved in the design and redesign of many of the District’s most celebrated public spaces, including the Tidal Basin, with its flowering cherry trees, and both Montrose and Meridian Hill Parks. He also designed parks and park systems in Missouri, Nebraska, New York, Maryland, Virginia, and South Carolina. A lecturer on civic design at MIT, University of Pennsylvania, and University of Illinois, Burnap authored Parks: Their Design, Equipment, and Use in 1916. Burnap likely took the Frederick job in an effort to spend additional time with his sister Grace, who was working at Hood College at the time in the music department. Court Park This important swath of land has been an important meeting ground for over 270 years, dating back to the county’s founding in 1748. As the courthouse lawn, it once was surrounded by an iron fence, that is said to have helped corral pigs and other livestock. The citizenry begged for its removal in the around the turn of the 20th century, allowing for the public to enjoy the grounds more fully. Court Park has become is today more commonly as Court House Square (or Court Square). In 1919, much discussion revolved around the removal of the decorative iron fountain located in front of the Courthouse front steps. This was a gift from resident James C. Clarke, a longtime railroad executive and namesake of Clarke Place on the city’s south side. Some wanted the iron fountain moved so a World War I monument/memorial could be put in its place. A change of mind came about, and so did a parcel of property two blocks away on the northeast corner of 2nd and Bentz streets. This would become the home for the war monument entitled “Victory.” The space would earn the name Memorial Park.  Carroll Park This was the original, “old school” portion of the Carroll Creek Linear Park. In 1907, Frederick alderman, and successful downtown merchant, David Lowenstein suggested putting a monument in the vicinity of where the Barbara Fritchie house had once stood. The legendary home had been partially destroyed in the Great Flood of 1868, and subsequently removed completely a short time later in an effort to widen the creek. Alderman Lowenstein went one step further by suggesting that a park be built on the west side of Carroll Creek surrounding Riehl’s Spring. This would become known as Carroll Park, a frequent scene of band concerts, camp meetings and unruly teenagers. Tourist Park Another park of note was located a few blocks west on West Patrick Street. This was the Tourists Park, an auto camp project of the Maryland State Roads Commission, and one of eight located on the National Road. Others existed in Elkridge, Cooksville, Conococheague, Hancock, Bellgrove, Frostburg and Negro Mountain. Supplied with all the conveniences a traveler may need, these places were practically small economy cabins in the same vein as the recently departed “Camp Cozy” in Thurmont. They were the forerunners of campgrounds (ala Jellystone Park) before the era of tow-able trailers and campers. Frederick’s tourist camp officially opened around 1922. This lasted for over a decade and would eventually become known by took the name of the Barbara Fritchie Motel and Tourist Cabins. John “Dutch” Faust from Pittsburgh operated this business for several years. Today this area is the home of the Way Station.  Reservoir (off W. 7th Street) as pictured in the 1873 Titus Atlas Reservoir (off W. 7th Street) as pictured in the 1873 Titus Atlas Reservoir Park An impressive municipal structure was completed in 1845—the City of Frederick’s reservoir works and grounds. Construction began in 1844 and the $90,000 project served as a better means to handle the growing town’s water needs. This municipal godsend replaced the former system of water connection stretching out to Catoctin Mountain, northwest of the city in the vicinity of Yellow Springs where wooden pipes carried water from an artesian well to a reservoir. The “new reservoir” was located at a place that would one day become the north end of Culler Avenue, just below West 7th street. The town “water-works” would be rebuilt in 1895 in the same location, but with a new capacity of 8 million gallons. An ornamental statue (of a woman with upraised cup in hand), was a hallmark at the reservoir. With the 1890’s renovation, the statue was converted into a showering fountain. When the 7th Street reservoir was rendered unnecessary due to advanced technology in municipal water supply, it became a recreational park. Today, you can still see remains of the reservoir’s retaining walls while visiting Max Kehne Park on West 7th Street. East Frederick Little League has their baseball field within the footprint of the old water source.  Pitching ace Max Kehne (ca.1947) Pitching ace Max Kehne (ca.1947) Fittingly, this park’s namesake, Max Kehne, was a standout ballplayer himself. His play as a youth gained him great accolades, and this would continue into adulthood. He was known best for his softball pitching. He was involved in leadership roles in a number of local activities including President of the Maryland Baseball Association and President of the Frederick Touchdown Club. After many years, Max Kehne entered politics and won election as a Frederick City Alderman in 1969. Sadly, Max Kehne died at age 45, the victim of a drunk driver on April 19th 1973, as he was traveling back to Frederick on I-70. Max Kehne Memorial Park was dedicated to this special man and athlete on May 22nd, 1977, four years after his death. His namesake park is adorned with a softball diamond as well.

4 Comments

richard schlecht

4/14/2016 08:39:04 am

Nice piece, Chris...thanks!

Reply

Pepper Scotto

4/14/2016 02:28:57 pm

Chris, this walk through the parks has been so delightful today. You always know how to educate us while we think we are just having a good time. Thank you

Reply

Harriet Wise

4/15/2016 03:48:41 am

Great project...and one of my favorite parks..I did not know it's history and have you to thank for enlightening me....Thanks.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorChris Haugh Archives

February 2024

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed