HSP HISTORY Blog |

Interesting Frederick, Maryland tidbits and musings .

|

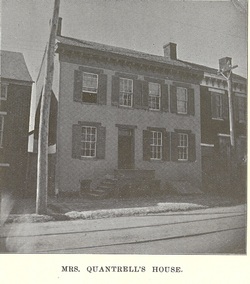

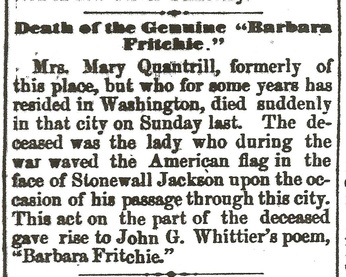

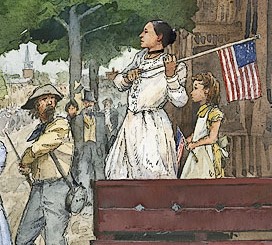

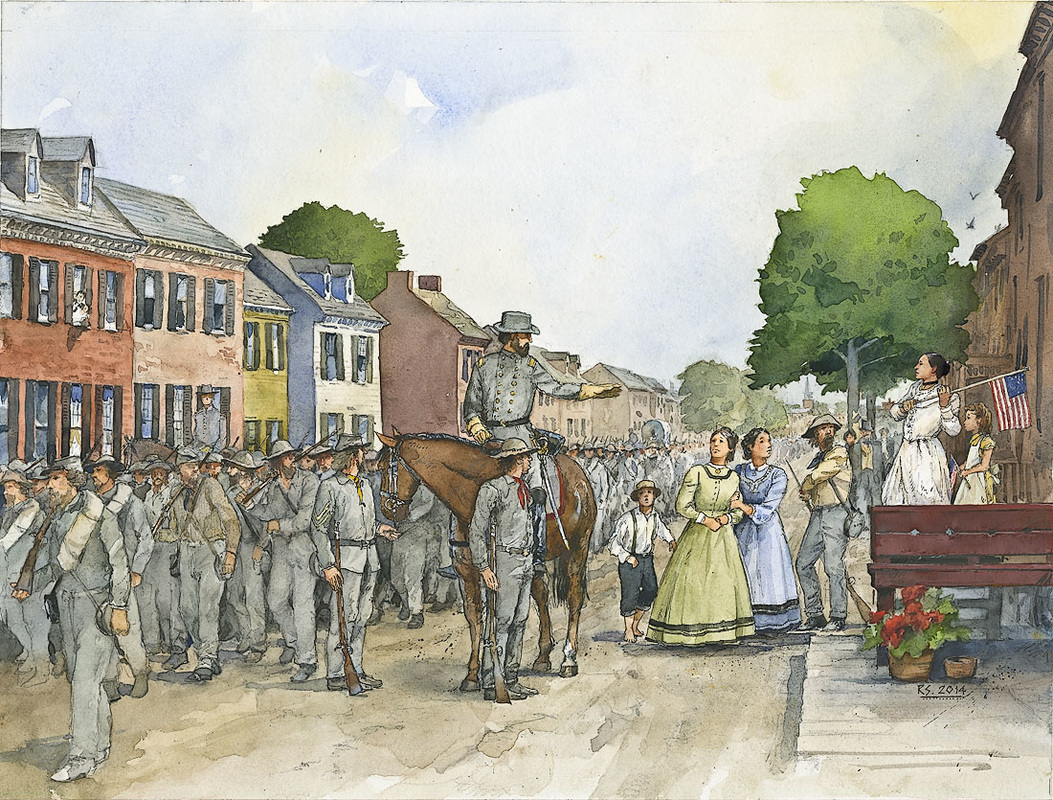

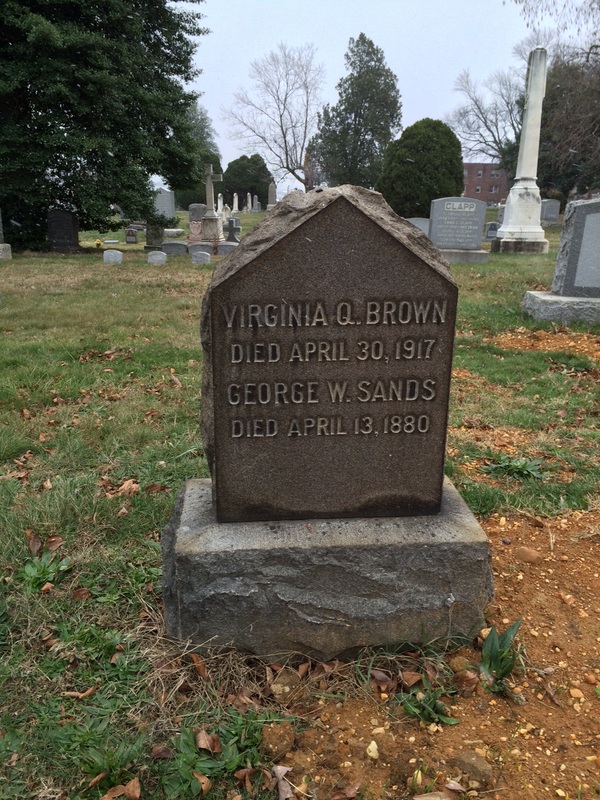

The other morning I had to drop my stepson Jack at Reagan National Airport. He was heading to sunny Orlando, along with classmates in the Thomas Johnson High School marching band, to perform at Disney World and have a great week of meeting and learning from other bands and students. I couldn’t just make the trip down to DC and come back home without a side trip, especially due to the fact that it was a Sunday morning—a rare and unfettered opportunity to take in one of the many attractions that our nation’s capital affords. I decided to take a detour from the George Washington Parkway and drive into the District via Memorial Bridge. I drove around the National Mall and contemplated an ultra-quick museum visit to one of the Smithsonians, or perhaps perform some quick research at the National Archives, but decided I didn’t have that much time available since I had people coming to my house that afternoon for a “get together.” I eventually opted to visit an “old friend,” one whom I have diligently studied, and gotten close to, for nearly 10 years—Mary S. Quantrill. I know the name may not necessarily “roll off the tongue” or ring a bell, but for lifelong Frederick residents and Civil War wonks it should. Instead, this woman was denied her place in the pantheon of American history. Born Mary Sands in Hagerstown in 1823, my subject grew up on Frederick's West Patrick Street, married and would eventually serve as a schoolteacher of girls in the location of her childhood home (220 W. Patrick). Mary’s husband, Archibald Quantrill, was the son of a War of 1812 officer, and spent most of his life in Washington, DC, where he worked as a newspaper typesetter. At the outbreak of the Civil War, Archibald thought it best that Mary and young children reside in Frederick with Mary’s elderly mother, as Washington could be a prime target for Confederate attacks. Mr. Quantrill was proven wrong in early September, 1862, when Frederick was the first, major "Northern" town Gen. Robert E. Lee would bring his C.S.A. army after crossing the Potomac River. Many know the story that the Confederates were basically given a cold reception, save for a smattering of Southern-leaning residents. Not getting the assistance he had hoped for, Gen. Lee headed west toward South Mountain, utilizing the National Pike to transport his vast army. West Patrick Street was part of this great road, and Mary Quantrill would have a front row seat for the "Rebel Parade" out of town which began in the early morning hours of September 10. She even had her Union flag in hand to send off the Rebel horde. Mary Quantrill made a lot of noise that day, and was certainly noticed by soldiers, officers and a number of Patrick Street residents. However she didn’t make a name for herself—or should I say, she didn’t get help from a Georgetown novelist (E.D.E.N Southworth) or Quaker poet from Massachusetts (John Greenleaf Whittier). In late summer of 1863, these literary luminaries had an Abolitionist agenda to tend to, and fast-tracked a work of prose that featured Mary’s feisty neighbor—a nonagenarian who lived a football field’s length down the street. The name of Barbara Fritchie (or Frietchie) rang true as not only Frederick’s heroine, but that of a nation, or at least the part of it that was intact as the Union at that time.  Barbara Fritchie, "the famous, other woman." Barbara Fritchie, "the famous, other woman." Dame Fritchie didn't live long enough to enjoy her fame, as she died at age 96, 11 months before the poem was published in October, 1863. On the other hand, Mary Quantrill lived for another 17 years, and found it difficult to escape the praise and adoration her former neighbor received for "starring" in the poem, and doing what she, herself, had done in displaying true courage and devotion to her Union cause in a daring act of West Patrick Street flag-waving. Amazingly, no one saw Barbara harass the Confederates on that fateful day. I could go on with this subject, as Mary certainly holds a place in my heart of hearts as the brave and brash woman who would never see her day in the limelight, not to mention the history books. Instead she was scorned for attempting to "hone-in" on Barbara’s fame. She died in 1879, and I have surmised it was a broken heart. The actual cause on the death certificate is cardiac disease, endocarditis...so close enough. You can learn more with these two links that feature my former writings on the subject, The Journal of the Historical Society of Frederick County (Fall 2008) and Maryland’s Heart of the Civil War: A Collection of Commentaries: http://www.historysharkproductions.com/past-projects.html http://browndigital.bpc.com/publication/?i=251369&p=106  Frederick Daily News, August 7, 1879 Frederick Daily News, August 7, 1879 Mary’s final resting is Glenwood Cemetery in NE Washington, DC, off Lincoln Ave. You will have trouble finding her, as she is buried in an unmarked grave. As a matter of fact, all the Quantrill’s are unmarked, except a daughter Virginia Quantrill Brown, who participated in the underplayed flag waving incident of 1862 on Mary’s front porch. I deduct that the name of Quantrill was Mud (or Mudd) for a couple of reasons. A cousin through marriage was the first to mess things up—this was William Clarke Quantrill, he of Quantrill’s Raiders fame. The second strike against Mary was an 1869 letter to the editor in which Mary gave a detailed first person account of her flag waving experience. This is when the major backlash started as many perceived Mary to be a “Pretender” trying to steal the limelight from Barbara Fritchie, one our “greatest American heroes.” Last Sunday morning, as I drove through the front iron gates of Glenwood, snow flurries began falling. From memory, I knew exactly where the lonely Quantrill grave plot was located. I parked, and walked over to the hallowed ground. I immediately felt pity for Mary all over again. As I stood there, I felt inclined, however, to tell Mary a bit of good news since last I had visited her. Thanks to some grant money, and a generous contribution from a local financial planner (Scott McCaskill) with help from the Frederick Woman's Civic Club, there is now an interpretive wayside marker in front of her old house (220 W. Patrick St. As I turned to walk away, I could have sworn I heard a faint woman’s voice say, “That’s great "history boy," now work on getting me a tombstone."

5 Comments

Mark VanBibber

1/22/2016 05:16:54 am

Great read about Frederick. I love this town and the history it offers. Thanks for sharing your passion.

Reply

Janet Whittaker

8/8/2016 04:39:13 am

Hi. Just found this opportunity to make contact, but my interest is in your article 'connecting the dots'. I believe your great great grandfather, Ambrose Jason Haugh was my great grandmothers brother . So my grandad was Als 1st cousin, my dad was Edwins 2nd cousin and I am your dads 3rd cousin. That makes us 3rd cousins once removed...I calculate! I have traced my Irish( Portlaw) family tree to England ( my direct line) , Australia, and now found this really interesting link with your family. It would be wonderful to compare notes. If you are interested please get in touch on the mail above and I will explain more. Jan Whittaker.

Reply

Nancy Bodmer

1/16/2017 04:01:53 am

You are the consument lover of history. You are an inspiration! Thanks!!!

Reply

Pamela Kay Quantrill

7/22/2021 05:05:48 am

Mary Quantrill was my great great grandmother. I never knew any of my dad’s side of the family. My dad (Harry C. Quantrill) was distant from his family when I was growing up. His parents died in 1952 a year after my birth. I have been trying to piece together his side of the family.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorChris Haugh Archives

February 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed